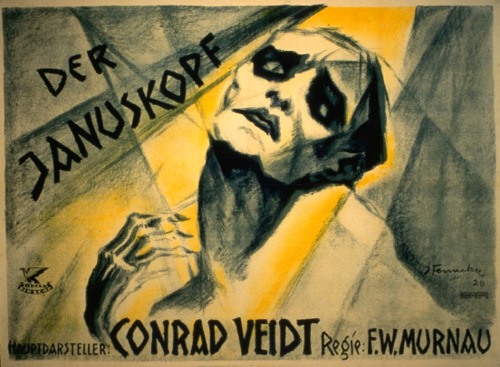

Over the past few months I’ve been looking into silent German cinema, one of the films that I’ve come across which has most intrigued me is Der Januskopf, starring Conrad Veidt and directed by F W Murnau.

The first I knew of this film was the poster, which is an absolutely gorgeous example of the Expressionist film posters produced by Josef Fenneker. Der Januskopf, like an awful lot of Veidt’s and Murnau’s early work is listed as a lost film which really does feel like a great loss to cinematic history. There are no known prints or negatives of this film, all that appears to have survived are stills and the script.

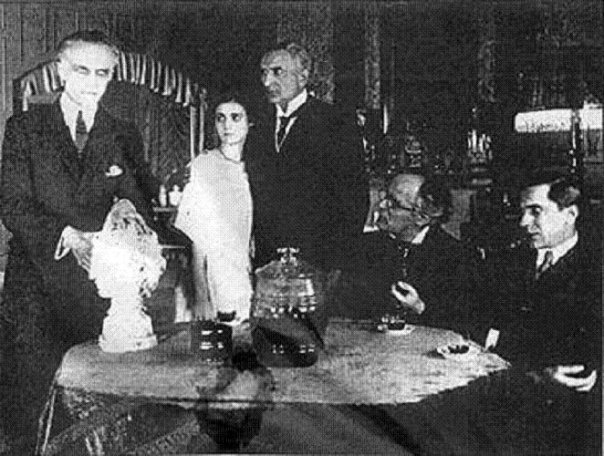

Synopsis: Coming upon a bust of Janus, the two-faced Roman deity, in a curio shop, Dr. Warren (Conrad Veidt) buys it on an impulse. Although he presents it to his fiance, Grace (Margaret Schlegel), she returns it to him, repulsed by its appearance. The doctor, who has been working feverishly on the enigma of the two sides of human nature, begins to fall under its influence. He concocts an elixir to separate the good and evil natures of man, as well as an antidote, with which to restore matters afterwards.

Synopsis: Coming upon a bust of Janus, the two-faced Roman deity, in a curio shop, Dr. Warren (Conrad Veidt) buys it on an impulse. Although he presents it to his fiance, Grace (Margaret Schlegel), she returns it to him, repulsed by its appearance. The doctor, who has been working feverishly on the enigma of the two sides of human nature, begins to fall under its influence. He concocts an elixir to separate the good and evil natures of man, as well as an antidote, with which to restore matters afterwards.

Quaffing the liquid himself, he transforms into Mr O’Connor (Conrad Veidt), a hideous, hunchbacked brute.

Quaffing the liquid himself, he transforms into Mr O’Connor (Conrad Veidt), a hideous, hunchbacked brute.

O’Connor lets a flat in Whitechapel, London’s criminal district, and commits all types of horrendous crimes, including beating an old man to death and raping Grace. (By some accounts, O’Connor also forces Grace into prostitution.) Warren finds that he turns to the transforming liquid more and more, and discovers – to his horror – that stronger and stronger doses of the antidote seem to be producing shorter and shorter periods of normalcy.

The day comes, when on the run from the police, he cannot return to his residence. (In a hallucinatory sequence, O’Connor bludgeons a young girl and – as a horrified Dr. Warren watches nearby – the image of the brute multiplies and intensifies. It is unclear from existing synopses where this segment occurred.) The chemist is out of the necessary chemicals, so – via a note – Warren’s old friend Utterson (Magnus Stifter; in some accounts of the screenplay, the character is named “Laue”) is sent to retrieve the chemicals from Warren’s laboratory; there are enough for one final transformation. In the presence of Utterson and Grace, O’Connor reverts to Warren. The shock is too much: Utterson dies from fright and Grace goes mad.

Distraught, O’Connor rushes back to his home to do away with himself. Taking poison, he sits down to write a full confession, but, as he writes, he changes yet again into the brute. A friend, who has hurried over to the house, finds the letter and the corpse of O’Conner, which is clutching the bust of Janus.

(This synopsis formulated from [Hans] Janowitz’s script and contemporary critique of the film.)

Conrad Veidt on Screen by John T. Soister

This is the synopsis as it appears in the book, though I’m pretty sure that in the end it should be Dr. Warren who is writing the note, and that it’s also the corpse of Dr. Warren who is found clutching the bust of Janus. It would seem to make more sense, but without seeing the film, it can’t be known for sure.

The script was written by Hans Janowitz, who, in 1918 had written Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari with Carl Mayer. It’s very obviously based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, though it’s believed that Murnau didn’t bother to secure the rights from the Stevenson estate, hence the subtle changes to names etc. In this case it seems to have worked out alright for Murnau, as no-one related to Stevenson bothered to challenge the film, however, it didn’t work out so well when, a couple of years later he based Nosferatu on Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Stoker’s widow disputed the film and won, all copies of Nosferatu were subsequently ordered to be destroyed. The weird result of this is that we still have Nosferatu but there are no copies of Der Januskopf, a film which, to my knowledge, was never so purposefully destroyed. I suppose in someway it might just be that order that preserved Nosferatu, when something is so deliberately removed, there’s always a few who will hide it away.

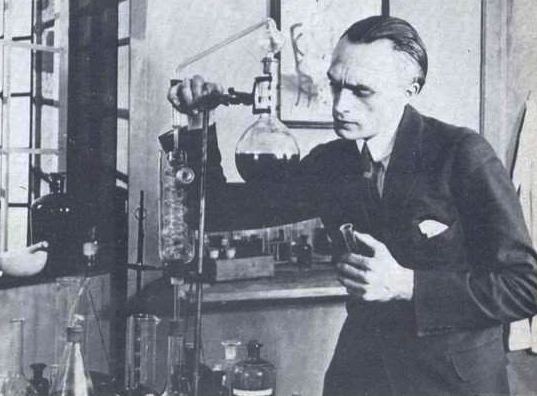

In 1924 Conrad Veidt filmed Orlac’s Hände, this film showcased Veidt’s ability as an expressionist actor, allowing him to convey a range of complex emotions purely through body language. I personally believe that Veidt was the master of this acting technique and he’s as hypnotic to watch as Chaplin’s balletic and beautifully choreographed pratfalls. If we view the scene when the hands start to control Orlac, I think we get some idea of what his portrayal of Warren/O’Connor may have been like.

Der Januskopf is the only time that Veidt ever starred alongside Bela Lugosi (he’s sat at the table, far right in the first still from the film). Lugosi would of course go on to be cast as Dracula in the 1931 Hollywood adaptation, but not before Veidt was considered for the part.

It’s perhaps Hollywood’s 1931 adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde that gives us a glimpse of what Veidt’s transformation from Warren to O’Connor could have been like. The part of Jekyll/Hyde is played brilliantly by Fredric March, and his transformation scene is one of the most striking in early horror.

The transformation is achieved on camera, there is no cutting away to apply make-up. It was achieved by manipulating different coloured filters in front of the camera lens, which revealed the various colours of make-up applied to March’s face. The different colours would register on the film depending on which filter was being used, making the shot seamless. If you watch the scene knowing this, you can spot the point when a filter is applied, not by watching the transformation of his face, but the transformation of his hands. Whilst I don’t believe this technique would have been used in Der Januskopf, I do think it shows what we could have expected from Veidt, as an expressionist actor he would have done as much of that transformation on screen as he possibly could. Perhaps it would be a little easier to view Veidt as am early method actor, the way he described his approach to acting certainly seems to have been all consuming:

And very soon I feel with a frightening intensity how the character, I have to play, is growing inside of me, how I am transforming into it. Quite a while before the shooting I can observe myself – even in normal life – moving differently, talking differently, glancing differently, behaving altogether in a different way as I usually would. The Conrad Veidt in me had gradually become the other, who I have to ‘represent’ and into whom my self had transformed by autosuggestion. Being possessed would best describe my state of mind.

Process of Transposition: German Literature and Film by Christiane Schonfeld

I would absolutely love a copy of Der Januskopf to be uncovered, films like this are the foundation stones of cinema, that we no-longer have the opportunity to see them is a real shame.