Super Super by Patrick Burgoyne (CR)

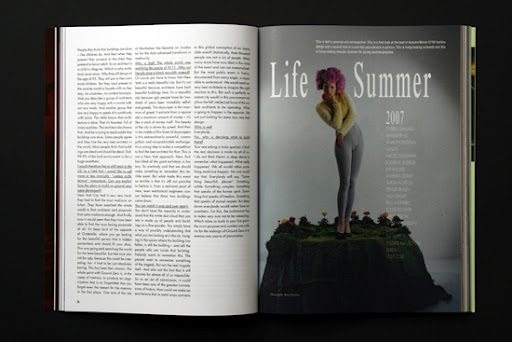

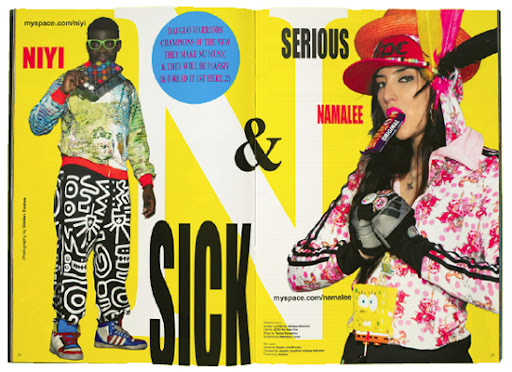

“People said ‘what the fuck is that? It looks like a clown’s been sick’.” Not necessarily the response you might hope for when launching a new style magazine, but it didn’t worry Steve Slocombe. As creative director of the fiercely trendy Super Super, Slocombe is used to being, shall we say, “challenged” about his work…

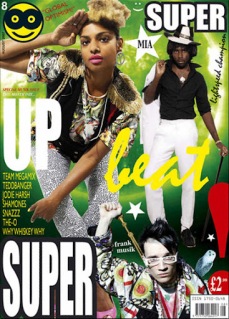

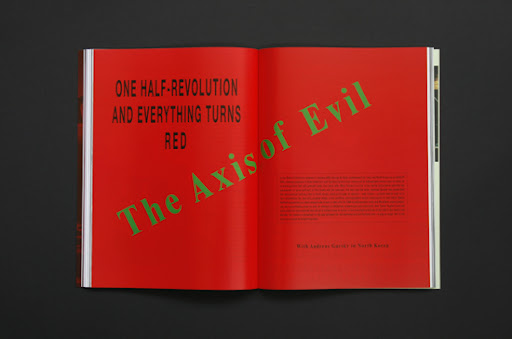

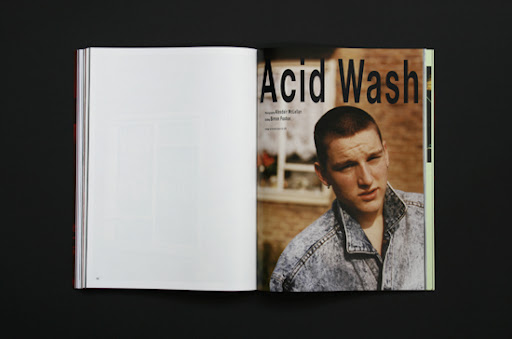

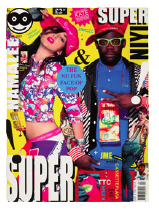

Launched early last year, Super Super’s wilfully distorted typography, day glo colours and total rejection of the holy tenets of magazine design are enough to give more mature art directors a fit of the vapours. It’s MySpace made flesh, with all the clashing cacophony that concept brings to mind.

And yet, according to Slocombe, what underlines it all is “harmony”. “There is nothing in Super Super that is empty or frivolous,” he insists, “everything is there for a reason”.

When it comes to style magazines, Slocombe has form, having previously been editor of Sleazenation. “I took Sleazenation to be one of the top four style magazines, but it was always going to be fourth on that list,” he says, recognising the strength of competitors i-D, Dazed and Confused and, at the time, The Face. “I could see a new generation with a new sensibility coming up so I thought, rather than be fourth, let’s get on this new thing and be first.”

A sign of what was to come came with Slocombe’s last issue at Sleazenation (May 2003). The publishers were away so he took the opportunity to introduce the freeform approach that Super Super has taken to such troubling extremes. He got the sack and went on to open a shop in Brixton with Namalee, former style editor at Sleazenation. The pair launched a magazine, Super Blow, out of which, 18 months ago, came Super Super.

Slocombe cites Scott King, with whom he worked at Sleazenation, as an influence on his design (particularly in “saying what you have to say efficiently”). However, the approach that King took at the magazine was deemed unsuitable for the new title. “At Sleaze, Scott wanted to do it in a book-ish style, but this new generation doesn’t read books so that’s not a relevant reference for them. This is the ADD generation. You have just one chance, one shot. Every time they open the magazine they have to get it.”

It was a period working for photographer Wolfgang Tillmans that most influenced Slocombe’s approach. A Fine Art graduate from St Martins, Slocombe’s role included helping Tillmans install his shows – a process that was, in itself, an artistic exercise. “We’d get a plan of the space and we’d turn up with work in all kinds of different sizes and respond to the space, arranging the work accordingly: it was an organic process about what work would sit best in certain situations,” he explains.

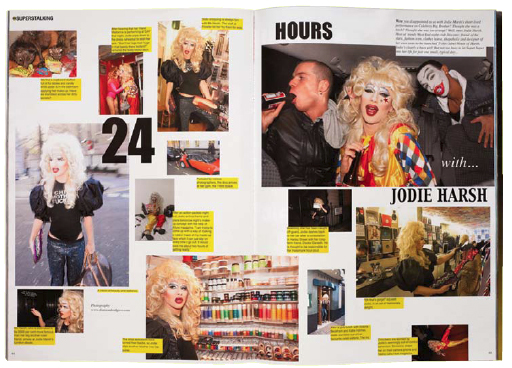

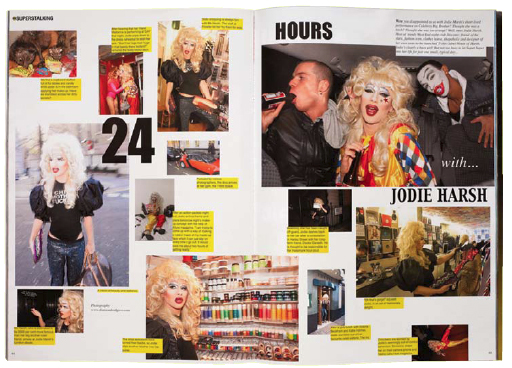

This, then, is the approach that he brings to designing Super Super. There is no predefined grid: Slocombe starts with the images (which may or may not be in focus) and arranges them so as to maximise the space, just as he and Tillmans would on the gallery wall. There are some rules: copy is set in blocks either 90mm or 40mm wide, at 10 point on 12 point leading or eight on 10, using either Helvetica or Times. But word and image rarely line up: “Things feel a lot more human if they are a fraction out,” Slocombe claims, “it’s about a sense of harmony and rhythm”. It’s what sets Super Super apart: “Magazines had become very machine like, very impersonal. Super Super is very human. It speaks to the reader very directly, removes the barriers. The values of the magazine are to be fun, to be positive, to say ‘have a go, you can do this’.”

While other magazines may seek to manipulate pace by contrasting full-bleed images with more detailed spreads, Super Super tries to cram in as much as possible onto every available inch of space. The reason, according to Slocombe, goes back to its readers’ alarmingly short attention spans. Typically aged between 14 and 24, they cannot be guaranteed to look at more than one spread in any particular issue, he claims, so each one has to embody all the values of the magazine. This, he would have us believe, is a generation with a different aesthetic value system. “In the Wallpaper* era, white was seen as expensive, but the young generation now think that if something has lots of colours, it must be more expensive. That,” he says “sums up the shift quite nicely.”

The magazine is not, Slocombe insists, anti-design. “That whole argument that you have to be either a follower of David Carson or of the Swiss School is not the debate we have now – I’ll take the best of both and anything else that’s around. The old way of things was movement followed by anti-movement, now the culture swallows the past and moves on instead of defining itself against what has gone before,” he argues. “I’m not against what has gone before, I just think this is more appropriate for here and now. At the core of the Swiss ideal is efficient communication – well, this is the most appropriate way to communicate to our audience.”

Wouldn’t it be more appropriate to communicate to them online? Or via their omnipresent mobile phones? “We know about print, Slocombe says, “and it’s much easier to make something feel human in print.”

Slocombe seems amused by the extreme reactions his magazine provokes. “I don’t deliberately set out to shock, I want people to say ‘Wow! It’s great’. It’s not meant to be anti-anything. People think it’s thrown together or anti-design, it really isn’t. It could be done entirely in black and white and it would still be recognisable as Super Super.” And what would that be? “Like nothing and everything you have ever seen before.”

Article from Creative Review

The Provocative Mr Meiré by Patrick Burgoyne (CR)

German art director Mike Meiré (above) is renowned in magazine circles for designing two of the most innovative magazines of recent times – brand eins and Econy. Both were celebrated for their clean, cool aesthetic appeal. His latest project, however, deliberately sets out to subvert all the notions of “good” design that his previous work nurtured so carefully. His redesign of cultural magazine 032c was described by Magculture.com as “willfully awkward”. Set against the standards of mainstream graphic design, it is, well, ugly. Here, Meiré explains why…

The New Ugly by Patrick Burgoyne (CR)

Interview with TwoPointsNet

“Pretty Ugly” is our 13th book as editors. Each book is very different and a great opportunity to learn more about a specific theme. “Pretty Ugly” was an interesting experience because we started with one idea about the movement and ended up with another. The toughest part about doing that book was acctually that there is so much material out there. The first layout, with all the material we received, resulted in over 900 pages and during the selection phase we even encountered more material. It took us weeks to boil down the book to 224 pages.

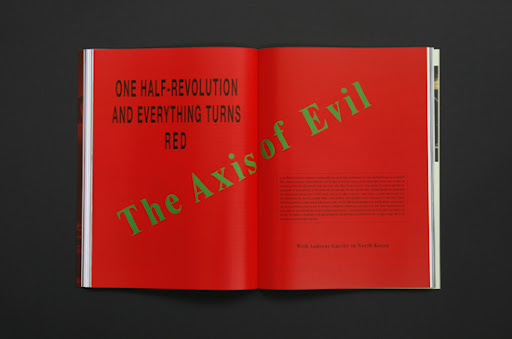

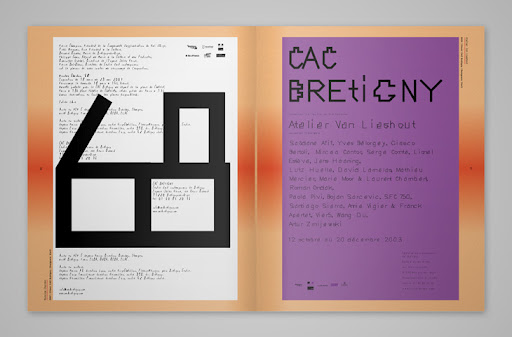

When we were putting the book together, we were aware of the reflections on the movement by Steven Heller, Michael Bierut (Design Observer) and Patrick Burgoyne (Creative Review). The last two articles cited Mike Meiré’s redesign of 032c (2007), a cultural, german magazine, in which he used stretched Helvetica (now it would probably be Arial) in the headlines, something that was done a lot in the 80s, but forgotten since. This simple gesture shocked designers who thought they’d seen everything. Meiré seemed to have found the last sacrilege in graphic design. Over the years the movement evolved into what we call “Pretty Ugly”.

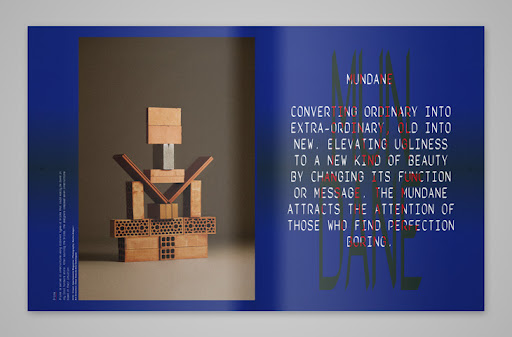

That the movement isn’t just about aesthetics. Of course, there are obvious aesthetic qualities: intentionally ‘bad’ typography; using system typefaces like Arial, Helvetica or Times; stretching them; having too much or too little letter or line spacing; deforming type on a scanner or a copier, etc. but behind the aesthetics there is more than just visual rebellion. We see a shift in the role the designer plays in the communication process. Design has been seen as the vehicle between sender and receiver. An invisible servant of information. Today, the designer has a voice which has become an important part of the communication process. Often we even see attempts to visualize the design process itself in the work.

You tell us. We might have some works that are pretty ugly. 😉 …, but to be honest we never really try to do anything trendy. In contrary, if something has become a trend we have lost the interest in it. With each project we try to develop an unique visual language based in the character of the product/firma/institution.

Working with uglyness isn’t that interesting, in fact, after doing that book, it is very hard for us to consider something ugly. What is really interesting though is the perception of ugly. In cases of Pretty Ugly it mostly means that something has been created, that society isn’t used to, that it doesn’t understand yet. Something that still has to be “learned”.

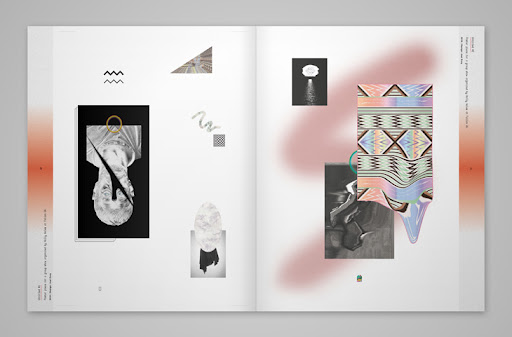

As we said earlier, there is too much good material out there. In graphic design you have studios like Superscript2 using amateur photography (p.2) or diagramms that seems to have been taken from PowerPoint (p.29). In photography you have Nacho Alegre, Ana Domínguez and Omar Sosa doing installations with bricks (p.46) or bread (p.56 & p.57), but as well Inês Nepomuceno photographing a still life of an aftermeal situation, making them look like paintings (p.54 & p.55) or Brea Souders intentional “mistakes” in “Seine With Fingers” or “Under My Thumb (Heat)” (p.76). In product design you have Maarten Baas’ “Plastic Chair in Wood” (p.61) and Jerszy Seymour’s “New Order” (p.67) chair, based upon the same cheap plastic chair.

The aesthetics will change, but we hope that some of the attitude will survive. We need more brave designers who are able to think out of the box. Mainly for three reasons: First, responsibility. A designer that sees him or herself as a co-author of the message begins to feel responsible for that message. It was easier to hide yourself behind the client’s messages when the designer was invisible. Second, initiative. Becoming a co-author instills entrepreneurship. Instead of waiting for commissioned work, designers nowadays are taking more initiative and inventing their own products or projects. Lastly, flexibility. A movement that understands design as a process is more flexible. It can more easily adapt, adjust and improve.

Trend Forecaster’s Handbook by Martin Raymond

The Trend Forecaster’s Handbook is a sharp, in-depth and highly visual textbook and teaching aid forstudents and academics keen to know more about the world of trends, trend forecasting, and consumer-insight techniques.

This “how to” book provides design students with skills to understand and track trends and use them to inform their research, design, and product development. With quotes, interviews, and case studies of key players.

Cult of the Ugly by Steven Heller

Interview with Brea Souders

Meine Bilder fallen eher in die Kategorie Pretty, würde ich sagen. Auch wenn meine Farbwahl und viele Kompositionen für den Betrachter oft unerwartet sind, sind sie schön. Sie beanspruchen nur mehr Zeit, bis man ihre Schönheit versteht.

Was definieren Sie als schön?

Ich möchte einfach ein Bild schaffen, dass sowohl visuell als auch psychologisch herausfordert. Viele meiner neuen Arbeiten sind autobiographisch inspiriert und besitzen Referenzen zu meiner Familie, meinen Vorfahren und meinen Erinnerungen. Dafür versuche ich mein Unterbewusstsein durch Mediatation und Hypnose zu erkunden. Für die jeweiligen Sujet kombiniere ich anschließend Modelle mit Materialien wie Pflanzen, Spiegeln, Stoff, Gipsabdrücken und Magazinen- und Bücherausschnitten.

Die besten Arbeiten sind schön und hässlich zugleich. Etwas, das schön ist, kann schnell langweilig sein und wird im nächsten Moment vergessen. Hässlich zu sein, ist dagegen wagemutig. Ich schätze Arbeiten, die angenehm anschauen sind. Aber ich denke erst über etwas nach, wenn es jenseits dessen liegt, was ich gewohnt bin, zu sehen oder zu diskutieren.

Interview with Martin Lorenz

There are moments, when leafing through the pages of Gestalten’s latest opus Pretty Ugly, that you’ll feel a little perplexed. Not by the stretched and layered type that practitioners of the New Ugly graphics movement use to obscure the messages contained in their work, nor by the fact that brands and organizations are trying to sell themselves with these deliberately obtuse images. What you’ll find so confusing, rather, is just how beautiful most of the projects appear, despite their creators’ best attempts at visual rebellion — a fact acknowledged by the book’s editors, Lupi Asensio and Martin Lorenz of the Barcelona-based firm twopoints.net, in its oxymoronic title. There are two reasons for this, Lorenz revealed when Sight Unseen sat down to interview him about the project: The first and most obvious is that we’re closer to the end of the New Ugly movement than the beginning, which is precisely what made the couple feel the time was ripe for a retrospective. Steven Heller has written about it, Urban Outfitters has embraced it, and we’ve gotten increasingly used to it — and desensitized to its shock value — ever since Mike Meiré used it to redesign 032c magazine in 2007. The second reason, and the one your editors found particularly compelling, is that somewhere along the line the New Ugly actually became less about rule-breaking and more about documenting process, with designers creating works that aim to expose the mechanics behind their boundary-pushing techniques. Read more of Lorenz’s thoughts about Pretty Ugly in our interview, then follow this link to purchase a copy of the book.

We were definitely playing with the title: For us it’s not pretty ugly, it’s pretty/ugly, and how little a difference there is between the two in this movement. But actually the book isn’t about being pretty or ugly at all. The whole New Ugly movement in the beginning was about trying to rebel against the established rules, and finding aesthetics that could trigger that effect in people. But now it’s not as much about trying to be rebellious, it’s more a contemporary methodology of working. It’s process-based; it’s thinking about the context in which your work is going to be shown. If you look at the examples of industrial design we included in the book, like Nacho Carbonell’s work or the Belgian couple Cox and Grusenmeyer, their aesthetic is really rough, and they do things that were forbidden before. But if you talk to them, they don’t say, “I want to do something ugly so I shock people.” They say, “What I’m doing is really honest — I’m showing the methodology behind my work.” Their work is constantly changing; it’s not something finished and super-polished that goes into a museum and can’t be touched anymore. They’re opening up and exposing something that maybe wasn’t shown before.

Yes, they’re creating work that looks rough and unfinished — something that’s still in progress. What’s interesting is that by showing this process and working with programs and typefaces like Arial that everyone can use, in a way it opened up the design process to young designers. You see this in fanzines, where people are doing graphics in Excel, and taking programs that are typically used by non-designers and using them to create sophisticated design.

Aesthetically speaking, certain visual effects are always repeating. So you have the Photoshop gradient, and the airbrush, and using that gray-and-white checkered Photoshop background. Then it’s using typefaces like Arial or Times, system fonts that everyone has. I haven’t seen Comic Sans—yet. The origins of that probably lie in the default design movement, which happened a decade ago in Holland. It was really popular to do design that didn’t look designed, using Times and Arial. This movement merged with the New Ugly movement. Then you see a lot this photocopy aesthetic: taking an image and photocopying it and having this bad texture, and sometimes moving the images while you’re copying them. This was done a lot in schools in the ’90s as an exercise, with photocopy machines. Nowadays since most of the young designers don’t have access to a photocopier, they do it with a scanner; in the book there’s a designer who refers to Renaissance paintings by putting roses on a scanner and moving them (above top), so you have this idea of nature against the artificial. The New Ugly movement really encompasses everything considered ugly, so using a Greek sculpture or column, or ’80s colors like mint and lilac, or Memphis-like textures as well.

That’s why we love the title so much. The publisher told us we shouldn’t tell anyone the title until the end, actually, because they thought the subjects in the book might get offended by it. Which of course wasn’t the case.

People still send us stuff trying to top each other in ugliness, but it’s really difficult to make something really ugly. You can do something pointless, or boring, but you can’t say that this is really ugly. This was part of the objective of this movement, to push the boundaries, and to get people to accept things they wouldn’t have accepted before. But what’s really important now is humor, and not taking yourself too seriously. It’s not like a ha-ha joke, and wanting to do funny things, but a kind of self-irony—saying, “We’re not going to take ourselves that seriously anymore. We’re going to put something out there, even if people inevitably say oh you’re such a bad designer, why are you using this font.” It’s a lot about that.

Most people point to Mike Meiré’s redesign of 032c as the turning point for New Ugly. Was that the moment it became recognized as a movement?

I think what 032c were doing by distorting type was certainly part of the New Ugly movement, but the function was totally different. Visually, of course, it was one of the first examples, but now the methodology behind the work is more important. Meire wanted to create an identity that looked nothing like other magazines out at the time; he used the design to differentiate it, but he wasn’t really opening up his process to others. It was a gesture. What you’re seeing now is different. When you look at Metahaven, for example, who did covers for Print magazine and a proposal for the Wikileaks identity, you see this multilayered design, a flexible visual identity that can be worked with in many different ways. It’s like the designer creates a toolbox for the client, and the client can create his own application.

Who else has played a key role?

For one, a school like Werkplaats Typografie, in Arnhem, where Armand Mevis and Karel Martens are teaching. If you go through their students’work, every second piece could be considered part of the New Ugly movement. A lot of people in Pretty Ugly did their postgraduate degrees there.

What work in the book do you think the average person would find the most jarring or confusing?

Maybe Andreas Ervik’s illustrations—in all the other pieces you can understand what the objective of the designer is, what he or she wants to express, but his work is really hard to read. A lot of the works in the book, if you see them for the first time, you might wonder if it’s actually design. In the context of the book, it’s obvious, but if you only saw one work in the context of everyday life, you probably couldn’t tell if the designer did it ugly on purpose or not, or whether it was done by an amateur. Most of the designers are trying to look amateur, and working really hard to forget everything they know. If you look at the books that Rob van den Nieuwenhuizen did for Onomatopee, for instance, he’s doing everything a good typographer would do, but then deliberately making it hard to read.

I think some people would be surprised to find that you included examples in the book that aren’t graphic design.

The graphic designers are maybe the most mainstream examples, but there are fashion designers who are doing even more interesting work within the movement, precisely because they’re not graphic designers — when they do illustrations, then it’s really getting ugly. They work a lot with textures, so at the end you don’t see anything anymore of their clothes, you just get a feeling for their work. Fashion designers like Andrea Crews often create two different presentations of their works: one normal shoot where they just present their line, and then a more abstract shoot. There’s also a New Ugly strain in industrial design, and we could have found examples in architecture as well. We really wanted to make this a fluid mixture between all the different disciplines. It happened in all of them at the same time.

That’s when you see that it’s a real movement — because it’s happening everywhere. It’s not just Mike Meiré who started something and everyone thought it was genius. It’s something that people felt the need for, to do something different and do something considered ugly, at least in the beginning. Everyone’s constantly trying to push the boundaries of what their profession is, and what they learned at school. Everything goes in waves. We went from strict rules to loosening up the rules, and most likely after that we’ll return to something strict again.

What rules people were they reacting against, exactly?

One of the most obvious is that typography is holy, and you never would choose any system typeface, or use a Windows program to design something. Within my personal experience, it all makes sense. We both studied in Darmstadt under a Swiss designer, and we learned the Swiss design rules, or really the German-Swiss design rules. Our professors were very strict about typefaces—you could use Univers, Frutiger, Helvetica, or if you wanted to be classic you could use some serif typefaces like Garamond, but these are all properly drawn typefaces. It’s not like someone who has a PC and needs to do a party flyer for his daughter’s kindergarten, with a bad version of Times or Comic Sans, and because he needs it really big, he stretches it to fill the whole page. Doing something like that was totally forbidden. And yet at that moment you still think you have all the freedom in the world—and then Mike Meire comes along and does this stretching typefaces thing that you’ve seen before on record sleeves like Gangstarr, or some ’90s bands, and then you see it in a magazine that’s supposed to be for intellectuals, and it feels kind of shocking. To many of us it was actually just shocking that there was still something to shock with; a big part of the attraction to that style comes from the fact that designers considered to be good broke rules we didn’t even know still existed.

What’s the status of the New Ugly now? Is it trendy? Is it becoming passé?

If a certain style gets popular, it inevitably becomes a trend, and then it starts to become empty. What’s more interesting is what the designers were actually doing when they were practicing it. Yes, it’s a trend now—when we were doing our research, we had over 120 people participating, and our first version had 900 pages and was very difficult to boil down. So you can see that it became a massive trend for young designers. Having Metahaven doing the covers of Print magazine—that wouldn’t have happened five years ago. It’s not mainstream, of course, but for many people inside the design world it means something’s established, you’re not just a freak anymore. There are people that accept what you’re doing. There’s also the work of Zak Kyes, who designs all the publications for the Architectural Association school in London, and of course Urban Outfitters. A lot of people in the book, like Joel Evey, have worked for them, and they did pretty trashy things for them as well. But we thought that now was a good time to make this book, because first you get a distance to what happened over the last 10 years, and then it’s to the point that it’s really interesting, and you start learning from it. We think that in a few years people will become tired of it, and the ones that are most interested in it will try to get distance from it and do something new again.

When that happens, what do you think will be New Ugly’s lasting effect?

You can’t go back anymore to a non-context-driven version of design, because this is the time we live in. Everything we do has an immediate response. Look at the social networks, and how institutions move inside these social networks—it’s not anymore one static message sent out by a company, you have to be much more flexible in the way you’re reacting. Seeing design as a process is a movement that can’t be stopped.

Pretty Ugly by TwoPointsNet

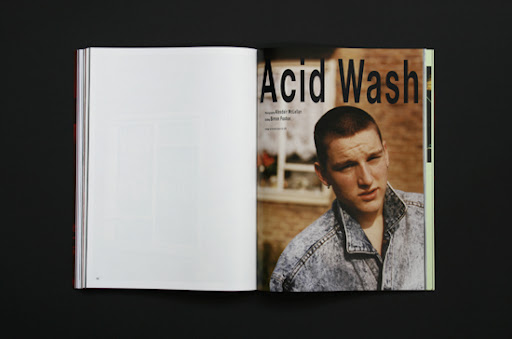

While art was allowed to be ugly, design had to function. Although for hundreds of years new artistic styles were established through aesthetic upheaval, new trends in graphic design and visual communication were, until recently, variations on what was generally considered to be appealing. But in the last few years, those working in these creative disciplines started to rebel. Dada-esque graphics or unreadable typography began to be used as a way to claim a unique style advantage.

“Pretty Ugly” is a diverse collection of these recent aesthetic, methodological and conceptual rampages not only in the fields of graphic design and visual communication, but also in product design, fashion design, art, and photography. The originators of this work consciously use unusual or negatively perceived forms, colors, and perspectives or transgresive process in an attempt to blaze new creative trails.

The variety of examples in “Pretty Ugly” may still be considered by some to be ugly, but they are already influencing the vanguard of tomorrow’s design.

Buy it HERE.