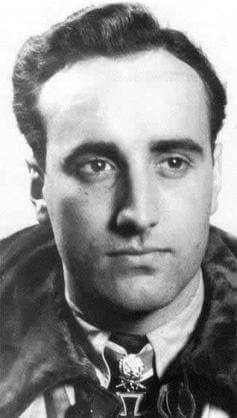

Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer was a German Luftwaffe night-fighter pilot and the highest-scoring night fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare. All Schnaufer’s 121 victories were in World War II, and mostly against British four-engine bombers. For his excellent combat record, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, Germany’s highest military decoration at the time, on 16 October 1944. He was nicknamed “The Spook of St. Trond”, from the location of his unit’s base in occupied Belgium. By the end of hostilities, Schnaufer’s night-fighter crew held the unique distinction that every member—radio operator and air gunner—was decorated with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Schnaufer was taken prisoner of war by British forces in May 1945. After his release a year later, he returned to his home town and took over the family wine business. He sustained injuries in a road accident on 13 July 1950 during a wine-purchasing visit to France, and died in a Bordeaux hospital two days later.

Family of Wine Merchants and Winery

Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer was born on 16 February 1922 in Calw, located in the Free People’s State of Württemberg of the German Reich, during the Weimar Republic era. He was the first of four children of mechanical engineer and merchant. His father owned and operated the family business, the winery Schnaufer-Schlossbergkellerei (“Schnaufer’s Castle Mountain Winery”), in the Lederstraße, Calw. The winery had been founded by both his father and his grandfather, in 1919, shortly after World War I. When his father unexpectedly died in 1940, his mother ran the business until the children took over the winery after World War II. The company then expanded the business and in addition to the winery offered wine imports, sparkling wines, and a distillery for wine and liqueur.

Early Years – Nazi Schooling

At an early age he expressed his wish to join an organisation of military character and joined the “Deutsches Jungvolk” (German Youth) in 1933. After completing his sixth grade he cleared the entrance exam to join the National Political Institutes of Education, a secondary boarding school (Napola) founded under the recently established Nazi state. Napola schools were to raise a new generation for the political, military and administrative leadership of the Third Reich. Schnaufer finished top of his class every year. At seventeen he graduated with his diploma in November 1939 with distinction. He also received the Reich Youth Sports Badge, the base-certificate of the German Life Saving Association, the bronze Hitler Youth-Performance Badge, and completed his B-license to fly glider aircraft.

Serious Interest in Flying

In 1939 Schnaufer was one of two students posted to the Napola in Potsdam, a Flying Platoon centralised for all the destined flyers from all the Napolas. Here he learned to fly glider aircraft, the DFS SG 38 Schulgleiter, and later on the two-seater Göppingen Gö 4 which was towed by a Klemm Kl 25.

Joins the Luftwaffe

Following his graduation from school, he cleared the entrance exam and joined the Luftwaffe on 15 November 1939 and underwent his basic military training at the “Fliegerausbildungs regiment” 42 (42nd Flight Training Regiment). His further flight training was at the “Flugzeugführerschule” FFS A/B 3 flight school for the pilot license. which he completed on 20 August 1940. He was trained to fly the Focke-Wulf Fw 44, Fw 56 and Fw 58, and the Heinkel He 72, HD 41 and He 51, the Bücker Bü 131, the Klemm Kl 35, the Arado Ar 66 and Ar 96, the Gotha Go 145 and the Junkers W 34 and A 35.

Advanced Flying Training

Schnaufer then attended the advanced FFS C 3,advanced flight school, and later the blind flying school “” BFS 2 from August 1940 to May 1941. This qualified him to fly multi-engine aircraft. During this assignment he was promoted to Cadet sergeant, and he became Second lieutenant on 1 April 1941. He was then posted for ten weeks to the “Zerstörerschule” (destroyer school). He was assigned radio operator Friedrich Rumpelhardt as an aircrew team on 3 July 1941. Schnaufer’s previous radio operator had proved unable to cope with aerobatics, and Schnaufer thoroughly tested Rumpelhardt’s ability to cope with aerobatics before they teamed up.

Volunteers to be a Night Fighter

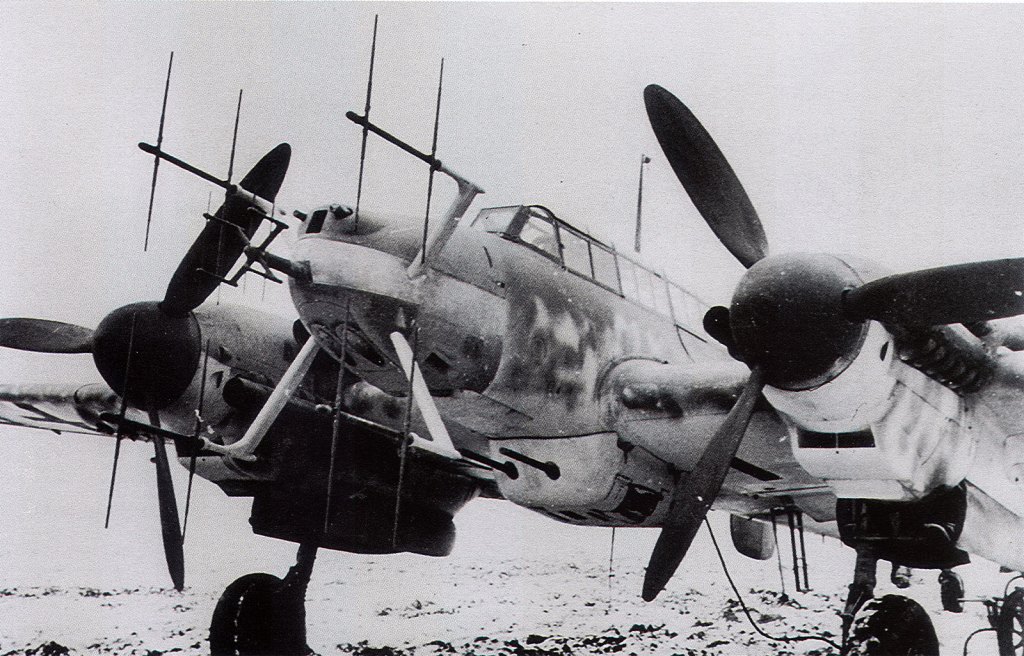

The two decided to volunteer to fly night fighters to defend against the increasing Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command offensive against Germany. After their training, the two were sent to the Nachtjagdschule 1 (1st night fighter school) near Munich, to learn the rudiments of night-fighting. The night fighter training was carried out on the Ar 96, the Fw 58 and the Messerschmitt Bf 110. Training at night focused on night takeoffs and landings, cooperation with searchlights, radio-beacon direction finding and cross country flights.

Joins Night Fighter Squadron

In November 1941, Schnaufer was posted to the II./NJG 1 (2nd group of the 1st Night Fighter Wing) at the time based at Stade near Hamburg. Here, Schnaufer was assigned to the 5th squadron of 1st Night Fighter Wing. The Bf 110’s of II./NJG 1 at the time were not equipped with airborne radar such as the Lichtenstein radar. Night fighter intercept tactics had matured since their early beginnings in July 1940, and II. Gruppe had already been credited with 397 victories.

Initial Night Intercept Concept

Missions against enemy bombers at the time were usually flown by means of ground-controlled interception, although the Luftwaffe was already experimenting with airborne radar. German air defence system, consisted of a series of radar stations with overlapping coverage, layered three deep, was conceived by Lieutenant General (equivalent to Major General) Josef Kammhuber and called “Kammhuber Line”. Conceptually, the system was based on a combination of ground-based radar stations, search lights and a fighter pilot controller officer. It consisted of a series of control sectors equipped with radars and searchlights and an associated night fighter. Each sector would direct the night fighter into visual range with target bombers.The controller had to vector the airborne night fighter by means of radio communication to a point of visual interception of the illuminated bomber. These interception tactics were referred to as the “Himmelbett” (canopy bed) procedure.

Unit Moves to Belgium – Little Initial Action

On 15 January 1942, II./NJG 1 transferred to Saint-Truiden in Belgium. Schnaufer entered front-line service at a time when the RAF was reassessing the air offensive against Germany. The effectiveness of British Bomber Command to accurately hit German targets had been questioned by the British War Cabinet Secretary David Bensusan-Butt who published the Butt Report in August 1941. The report in parts concluded that the British crews failed to navigate to, identify, and bomb their targets. Although the report was not widely accepted by senior RAF commanders, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, instructed Commander-in-Chief Richard Peirse that during the winter months only limited operations were to be conducted. Flight operations were also hindered by bad weather in the first months of 1942, so II./NJG 1 only saw very limited action during that period.

Channel Dash Operation

On 8 February 1942, II. Group was transferred to Koksijde Air Base without having scored any victories while stationed at Saint-Truiden. The objective of this assignment was to give the German battleships “Scharnhorst” and “Gneisenau” and the heavy cruiser “Prinz Eugen” fighter protection in the breakout from Brest to Germany. The Channel Dash operation (codenamed Operation Cerberus) of German Navy between 11–13 February 1942. The operation was to support return of the German ships to German bases as Britain planned invasion of Norway.

Operation Donnerkeil

In support of Operation Cerberus, the Luftwaffe under the leadership of General of the Fighter Force, Adolf Galland, formulated an air superiority plan dubbed Operation Donnerkeil for the protection of the three German capital ships. II./NJG 1 was briefed of these plans on the early morning on 12 February. The plan called for protection of the German ships at all costs. The crews were told that if they ran out of ammunition they must ram the enemy aircraft. To the relief of the night fighters they were assigned to the first-line reserves. The operation, which took the British by surprise, was successful and the night fighters were kept in their reserve role.

Repeat Unit Relocations – Yet No Contact With Enemy

On the evening of 12 February, II./NJG 1 was relocated to Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. On the afternoon of 13 February, Schnaufer flew a reconnaissance mission over the IJsselmeer and the North Sea and then relocated to Westerland on the island of Sylt near Denmark border. They further relocated to Aalborg-West in north Denmark from where they made a low-level flight in close formation over the Skagerrak, landing at Stavanger-Sola in Norway. Over the following days they operated from the airfield at Forus in Norway, making a short-term landing at Bergen-Herdla in Denmark. In total, Schnaufer made two operational flights without contact with the enemy. Following this assignment they relocated to5th squadron’s new base in Germany at Bonn-Hangelar.

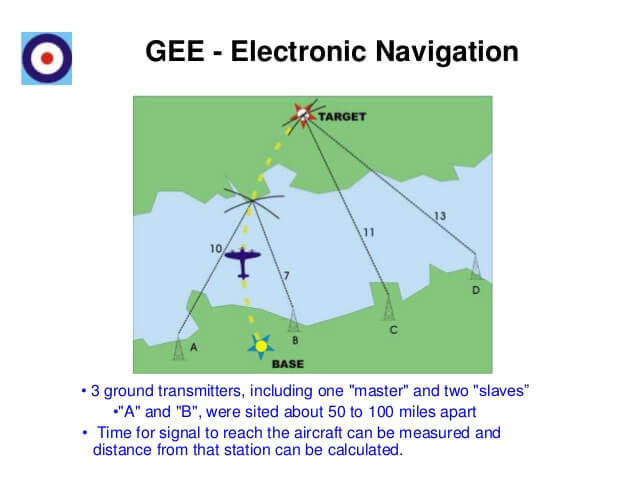

British Plan Area Bombing

Following the detailed analysis of the Butt Report, the British High Command made a number of decisions in February 1942 that changed the nature of the bomber war against Germany. On 14 February, Air Chief Marshal Norman Bottomley issued the “Area Bombing Directive”, which lifted the restrictions placed on the bombers in 1941. Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, commonly known as “Bomber” Harris, was appointed commander-in-chief of Bomber Command. These decisions, coupled with the introduction of Gee, a radio navigation system which enabled better target-finding and bombing accuracy. It essentially measured the time delay between two radio signals to produce a fix, with accuracy on the order of a few hundred meters at ranges up to about 350 miles (560 km).

First 1,000 Bomber Allied Raid – Operation Millennium

This led to the first Allied 1,000 bomber raid. In Operation Millennium, the RAF targeted and bombed Cologne on the night of 30/31 May 1942. Schnaufer did not participate in the missions in defence of Cologne. The “Himmelbett” procedure had limitations in the number of aircraft which can be controlled. Therefore, only the most experienced crews were deployed, and Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer, who had yet to achieve their first aerial victory, were left out. Prior to Operation Millennium, Schnaufer had been appointed TO (Technical Officer) on 10 April 1942 and was located at Saint-Truiden again. As a Technical Officer, Schnaufer was responsible for the supervision of all technical aspects such as routine maintenance, servicing and modifications of the Gruppe. In this role he was no longer a member of the 5. Staffel but was then a member of the staff of II./NJG 1.

First Aerial Victory – Ground Controlled Intercept

Schnaufer claimed his first aerial victory on their thirteenth combat mission flown one day after the attack on Cologne on the night 1/2 June 1942. Nominally this was the RAF’s second 1,000 bomber raid against Germany, although the attacking force actually numbered 956 aircraft. Schnaufer shot down a Handley Page Halifax south of Louvain in Belgium. The aircraft probably was Halifax W1064 from No. 76 Squadron piloted by Sergeant Thomas Robert Augustus West, which was shot down at 01:55 on 2 June 1942 and crashed at Grez-Doiceau, 15 kilometres south of Louvain. West and another member of the crew were killed. This victory was achieved by ground-controlled interception through the Kammhuber Line. Once near to the target, Rumpelhardt had visually found the bomber and directed Schnaufer into attack position from below and astern. The Halifax caught fire after two firing passes. During this mission the Himmelbett flight officer vectored them to a second bomber, a Bristol Blenheim. The attack had to be aborted after Hauptmann (Captain) Walter Ehle shot down the bomber from a more favourable attack position.

Schnaufer Gets Hit – Lands Back Safely- Hospitalised

On 2 June 1942 itself, a little later, around 3 PM, they spotted another target. Schnaufer made two unsuccessful attacks. During their third attack, which closed the distance to 20 metres (66 ft), they were hit by the defensive gunfire. Schnaufer was hit in his left calf, the port engine was burning, the rudder control cables were severed, and an electrical short circuit caused the landing lights to be permanently on. Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer considered bailing out but decided to make an attempt for their home airfield after they managed to put out the flames and restart the engine. While Rumpelhardt made radio contact with the Sint-Truiden airbase, Schnaufer landed the aircraft without rudder control and on ailerons and engine-power alone. This was the only time that their aircraft sustained damage in combat or any member of the crew was wounded. Both Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer were awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class for their first aerial victory. Schnaufer had hoped that he could stay on active duty and that the bullet lodged in his calf would isolate itself. However, he had to be admitted to a hospital in Brussels from 8–25 June for surgery. Rumpelhardt was given home leave until 26 June while Schnaufer was in the hospital.

Back in Action – More Aerial Victories

Schnaufer had to wait two months to achieve another victory, claiming the destruction of two Vickers Wellingtons and one Armstrong Whitworth Whitley within the space of 62 minutes in the early hours of 1 August. The first Wellington, originally identified by the crew as a Halifax, was severely damaged 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) above the Netherlands and forced to crash land, killing the air gunner at 02:47 hours. The second Wellington was shot down 3,800 metres (12,500 ft) over Brussels, killing everyone on board at 3:17 hours. Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer flew their first combat mission with the Lichtenstein radar on the night 5/6 August 1942. Though they managed to make contact with an enemy aircraft they failed to shoot it down.

Becomes an Air Ace

On the night of the 24/25 August 1942, Schnaufer became an ace (his fifth aerial victory), when he filed a claim for another Wellington, probably BJ651, which was shot down with the loss of Sergeant Eric Bound and crew. This was the first time Rumpelhardt had guided him into contact using the FuG 202 Lichtenstein B/C UHF-band airborne radar. His next claim was made on the night of 28/29 August. This was probably No. 78 Squadron Halifax II W7809, piloted by Sergeant John A. B. Marshall of the Royal Australian Air Force. All crew died in the crash. On the night of the 21/22 December 1942, Schnaufer shot down Avro Lancaster R5914; his first victory against this type. The aircraft crashed at Poelcapelle, killing three on board. It was Schnaufer’s seventh victory. Schnaufer may also have been responsible for the destruction of another Lancaster that night. Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer had attacked a Lancaster and observed it catching fire followed by the aircraft plunging earthwards. German Captain Wilhelm Herget of the 4th Night Fighter Wing had also attacked a four-engined bomber in the same vicinity. The draw decided in favour of Herget who was given credit for the destruction of the Lancaster.

Rumpelhardt Temporary Grounded

By the end of 1942, Schnaufer’s total stood at seven, with three victories recorded on the night of 1 August, which had earned him the Iron Cross 1st Class in early September 1942. From 29 November to 16 December 1942, Rumpelhardt was confined to the hospital bed with high fever. Rumpelhardt then attended various officer training courses from February to October 1943. Between 14 May to 3 October 1943, Schnaufer claimed 21 further aerial victories in Rumpelhardt’s absence; 12 with four different radio operators.

Few Bomber Command Raids in Schnaufer’s Unit Area of Action

II./NJG 1 saw little action in the first few months of 1943, and Schnaufer did not claim his next aerial victory until 14 May 1943. II./NJG 1 Himmelbett control areas were located to catch the bombers heading for the Ruhr Area. Bomber Command had made only ten major attacks in that region from January to April 1943. Consequently, II./NJG 1 claimed no victories in January, two in February, one in March and three in April.

Battle of Ruhr – Action Begins

Schnaufer’s number of aerial victories increased again during the Battle of the Ruhr. Schnaufer, with Baro as his radio operator, shot down a No. 214 Squadron Short Stirling R9242 at 02:14 hours on 14 May 1943 on an attack mission against Bochum. Four members of the crew, including pilot Sergeant Raymond Gibney, lost their lives. His next victory on the same mission at 03:07 hours, his 9th overall, a No. 98 Squadron Halifax JB873 returning from Bochum. The captain, Sergeant G. Dane and co-pilot Sergeant J. H. Body were killed in the crash. On the night of 29/30 May, Bomber Command attacked Wuppertal. Schnaufer and Baro took off on the first wave at 23:51 on 29 May and returned at 02:31 on the 30 May. They shot down two Stirlings, one at 00:48 and the other at 02:22, and one Halifax at 01:43.

Promoted First Lieutenant – Awarded the Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe

In June 1943, Schnaufer filed claims for a further five aerial victories. Schnaufer and Baro shot down a Stirling from No. 218 Squadron on 22 June 1943 at 01:33. With Baro on the radio and radar, they managed another victory over a Wellington on 25 June 1943 at 02:58. On 29 June 1943, the two shot down three bombers in another attack on Cologne, a Lancaster and two Halifax bombers at 01:25, 01:45 and 01:55 respectively. This brought the number of aerial victories he was credited with up to seventeen. Schnaufer was promoted to First lieutenant on 1 July 1943. Schnaufer claimed his last two aerial victories with Baro operating the radio on the night of 3/4 July, Bomber Command had again targeted Cologne. Their victims were a No. 196 Squadron Wellington shot down at 00:48 and a No. 149 Squadron Stirling at 02:33, bringing his total to 19 victories. His next radio operator was Oberleutnant Freymann. They shot down a No. 49 Squadron Lancaster, on another Cologne bombing mission, on 9 July 1943 at 02:33. He was awarded the Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe on 26 July 1943.

Operation Gomorrah – British Introduce Chaff – German Counters

In mid-July, the Battle of the Ruhr was coming to an end and Bomber Command refocused its efforts on the port city of Hamburg in northern Germany. The codename for the attack was Operation Gomorrah – the objective was the destruction of Hamburg. The operations began on 24 July 1943 and during four major night-attacks by the RAF and two minor day-attacks by United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) between 40,000 and 50,000 civilians were killed. To counter the mounting success of the German night fighter force, which was directly attributed to the introduction of the Lichtenstein radar, the RAF introduced Window (Chaff). Window was a radar countermeasure in which aircraft spread a cloud of small, thin pieces of aluminium which effectively made it impossible for the German radar operator to identify the genuine target. Saturation of the Himmelbett control areas by a bomber stream and the introduction of Window practically made the previous Himmelbett procedure obsolete. This was also evident to the German high command.

To counter these British measures two new strategies were pursued, Wilde Sau (Wild Boar) and Zahme Sau (Tame Boar). Wilde Sau, conceived by Hans-Joachim Herrmann, was a technique by which the RAF bombers were mainly engaged by single-seat fighter planes, illuminated by searchlights, over the target area. The Zahme Sau procedure, proposed by Viktor von Loßberg, called for a night fighter to infiltrate the bomber stream. The position, altitude, and general direction was then broadcast. The information was received by other night fighters, who navigated to the bomber stream by themselves. In Zahme Sau, the German night fighters were tracked and radio-controlled by means of Y-Control. Schnaufer did not make any claims during Operation Gomorrah. Their next success came when he and Freymann shot down a Lancaster on 10/11 August 1943 at 00:32. The target that night was Nuremberg and it was the first aerial victory of the entire German night fighter force achieved by Y-Control. This was also the last victory with Freymann and his last as a member of II Group.

Y-Control Fighter Guidance System

Allied jamming of existing VHF voice radio links and MF navigation beacons was becoming extremely effective. The Y-Control System was based on the work done for the Y-Gerät system of bomber guidance. There were differences in frequency and a dedicated transponder was not required. The system worked by using sites known as Y-Stations. Each station had 5 radio operation systems. Each consisted of an omnidirectional transmitter an omnidirectional receiver and a direction finder. This allowed each site to control 5 fighters. The transmitter would send out a signal which was picked up by the “FuG16ZY” system in the fighter (known as the Y Fighter), this repeated the signal back on a frequency 1.9 MHz lower than the transmitted frequency. Using the direction finder (DF) the angle was measured. Range was calculated by a timing system connected to both the transmitter and the omnidirectional receiver. Height could not be measured. However voice could be transposed onto the ranging signal allowing the ground controller to talk and listen to the pilot of the plane he was controlling, hence the pilot could report altitude when requested to do so. A Y-Fighter was part of a group of fighters intercepting an allied bomber stream. The Y-Fighter was painted a distinctive colour and the rest of the flight simple followed him. The flight leader could also listen into the ground controller channel and hear what the ground controller was saying while also being able to talk to the flight. The Y-Fighter was never the group controller. The system was susceptible to jamming on the FuG16ZY wavelength but was at least partially usable for the rest of the war. Controllable range was approx 250 km depending on aircraft height. Relay stations could be used to extend the radio range. The radio system used was a modified FuG16 radio. The Y-Site also contained other systems such as radio communications for talking to area control.

Squadron leader of 12.Staffel/NJG 1

Schnaufer was transferred to IV./NJG 1(4th group of the 1st Night Fighter Wing), based in the Netherlands at Leeuwarden Air Base, where he was appointed Squadron Leader of the 12./NJG 1(12th squadron of 1st Night Fighter Wing) on 13 August 1943. At the time, IV./NJG 1 was under the leadership of Group Commander Hans-Joachim Jabs (50 night victories). Jabs’ first impression of Schnaufer was not entirely favourable. Shortly after Schnaufer’s arrival, on one of his first missions in Leeuwarden, Schnaufer had taken right of way during taxiing. This forced Jabs into second place in order of takeoff, an act of insubordination and perceived as arrogant by Jabs.

Initail Y Control Missions

Schnaufer, who had received the German Cross in Gold on 16 August 1943, flew his first operational mission with 12./NJG 1 on the night of 17/18 August 1943. Bomber Command had targeted Peenemünde and the V-weapons test centre that night. Schnaufer, who had been tasked with leading one of the first Zahme Sau missions under Y-Control, had to abort the mission early due to engine trouble. Around mid-September 1943, the two-man Bf 110 crew was augmented by a third member, sometimes referred to as air mechanic or air gunner. The reason for this was that the decline of the Himmelbett procedure, the introduction of the broadcast procedure Zahme Sau, and the growing threat of RAF intruder night fighter operations, had necessitated the need for another pair of watchful eyes to the rear. Under Officer Wilhelm Gänsler, who had already contributed to 17 claims made by Captain Ludwig Becker (night fighter Ace with 44 victories), was Schnaufer’s new lookout man. With Handtke and Gänsler as his crew, Schnaufer claimed his 26th aerial victory on 23 September 1943 over a No. 218 Squadron Stirling during a Wilde Sau intercept mission.

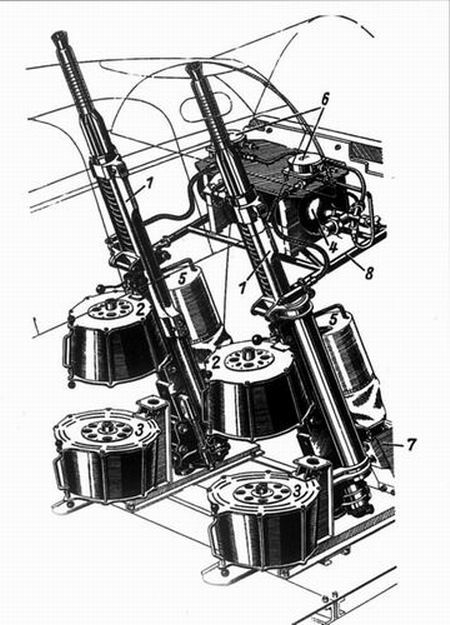

Upward-firing Auto-cannon “Schräge Musik”

Following its May 1943 debut in action, during the second half of 1943, Schnaufer and his crew began experimenting with upward-firing auto-cannons, dubbed “Schräge Musik“. This allowed the night fighter to approach and attack the bombers from below—outside the enemy crew’s usual field of view. An attack by a Schräge Musik-equipped night fighter typically came as a complete surprise to the bomber crew, who realised a night fighter was close by only when they came under fire.

It is not exactly known when Schnaufer’s Bf 110 was equipped with Schräge Musik. Rumpelhardt stated that the weapons system was installed prior to his return from officer training. Reportedly Schnaufer’s 20 to 30 victories were claimed using the upwards firing cannons. Later the Japanese also fitted such canons on their night fighters.

Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for 42 victories

Rumpelhardt had returned from his officer training courses in early October 1943 and rejoined Schnaufer’s crew. Gänsler, Rumpelhardt and Schnaufer claimed aerial victories 29 and 30 on 9 October. Schnaufer was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for 42 victories on 31 December 1943. On the night before his 22nd birthday, on 15 February 1944, Schnaufer and his crew claimed aerial victories 45 to 47. Bomber Command had sent 561 Lancasters and 314 Halifax four-engined bombers, supported by de Havilland Mosquito night-fighters and bombers, destined for Berlin. Schnaufer, who had been suffering from stomach pains all day, and his crew returned to Leeuwarden at 00:14. Rumpelhardt had been the first to congratulate him on his birthday over the intercom. Their fellow airmen had prepared a birthday celebration.

Appendicits Operation – Break from Flying Operations

The stomach pains had become unbearable and Schnaufer was taken to a hospital with appendicitis. He stayed in the hospital for about two weeks before, together with Rumpelhardt, he went on vacation back home. Carelessly lifting his suitcase, he burst his stitches, resulting in further hospitalisation. He flew his first mission after these events on 19 March 1944.

Group commander of the IV./NJG 1 – Ace in a Day

Schnaufer was appointed Gruppenkommandeur IV./NJG 1 on 1 March 1944, taking over command of the from Jabs who was given command of NJG 1, He was promoted to Hauptmann (Captain) on 1 May 1944. Schnaufer became an ace-in-a-day for the first time on 25 May 1944 when he claimed five RAF bombers shot down between 01:15 and 01:29 for victories 70 to 74. The bomber raid had targeted the railway marshalling yard at Aachen.

Operation Overlord – Normandy Landing

On 6 June 1944, the Western Allied forces landed in Normandy, during Operation Overlord. In support of the invasion of Normandy General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, assigned Bomber Command to support the ground forces. On the night of 12/13 June, Schnaufer claimed his first victory following the invasion when 671 bombers attacked various railway targets in France. Schnaufer claimed three bombers shot down that night, the first was a Lancaster and the second and third were a Lancaster or Halifax, between 00:27 and 00:34.

Awarded Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords

Schnaufer was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves on 24 June following four aerial victories claimed on 22 June, which took his total to 84 victories. For Schnaufer, July 1944 was less successful than the previous three months. He claimed two bombers on the night of 20/21 July and three on 28/29 July, taking his total to 89 aerial victories. One day later, on 30 July, he received a letter from Göring telling him that he had been awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. Hitler himself made the presentation. It is said that when he came to the presentation his first words were, “Where is the night fighter?” Shortly following the presentation, both Rumpelhardt and Gänsler received the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross on 8 August. His crew was the only night fighter crew in the entire Luftwaffe of which all crew members wore this decoration.

Unit Relocated Due Heavy Allied Bombing

In early September 1944, NJG 1 was forced to abandon its airfields in the Netherlands and Belgium. Continuous heavy attacks by RAF and USAAF bombers and strafing by Allied fighter-bombers rendered the airfields unsuitable for operations. On 2 September, VI./NJG 1 relocated from Saint-Truiden to Dortmund-Brackel.

Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

Schnaufer achieved his 100th victory on 9 October 1944, when he claimed two bombers shot down from an attack force of 415 bombers targeting Bochum. He was mentioned in the Wehrmachtbericht ( the daily Wehrmacht High Command mass-media communiqué and a key component of Nazi propaganda during World War II) on 10 October 1944 and awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds on 16 October 1944. He was the 94th Luftwaffe pilot to achieve the century mark.

Wing Commander of Nachtjagdgeschwader 4 – The Youngest at 22

Schnaufer was then appointed Wing Commander of NJG 4—4th Night Fighter Wing, at Gütersloh on, on 20 November 1944. He was the youngest Wing Commander in the Luftwaffe at the age of 22. Schnaufer and his crew flew to Berlin on 27 November 1944 for the official presentation of the Diamonds to the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords by Hitler. Schnaufer and his crew were filmed for the German newsreels. Three days later they returned to Gütersloh.

Becomes Leading Night Fighter

Schnaufer became the leading night fighter pilot on 9 November 1944. Schnaufer surpassed Colonel Helmut Lent’s record of 102 night-time victories, after he claimed three Lancasters shot down from a force of 235 Lancasters from No 5. Group which attacked the Dortmund-Ems Canal. Schnaufer, whose victory total stood at 106 at the end of 1944, failed to shoot down a single bomber in January 1945. It was his first month without filing a claim since April 1943.

Offered Post of Inspector of the Night Fighter Force – Declines

Schnaufer was ordered to Carinhall, the residence of the Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, on 8 February 1945. Göring informed him about the intent to appoint him as Inspector of the night fighter force, a role held by Colonel Werner Streib, a friend and mentor of Schnaufer. He politely excused himself by saying that he would better serve the German cause fighting the enemy. Göring was convinced and Schnaufer remained in active flying.

British Honorary Title “The Spook of St. Trond”

The British propaganda radio station (Soldiers’ Radio Calais) congratulated Schnaufer on his 23rd birthday on 16 February 1945. The radio station explicitly addressed the soldiers of NJG 4 stationed in Gütersloh followed by the song “The Bogeyman” praising him for the honorary title given to him by the British bomber crews “The spook of St. Trond“.

Second Time Ace in a Day – 9 Victories in a Night

Schnaufer’s greatest one-night success and the second time he became an ace-in-a-day was on 21 February 1945, when he claimed nine Lancaster heavy bombers in the course of one day. Two were claimed in the early hours of the morning and a further seven, in just 19 minutes, in the evening between 20:44 and 21:03.

Operation Gisela

Schnaufer was one of the influential figures that instigated a brief return to mass intruder operations over England named Operation Gisela. General of Night Fighters, Lt. General Schmid, and de facto command-in-chief of the German Night Fighter Force until November 1943, had long since desired to return to intruder operations over Bomber Command bases in England. The proposals met resistance from General Staff. Eventually, in October 1944, Schmid won support to begin planning an operation. Schnaufer voiced his support also. In his experience, he had regularly pursued RAF bombers to the English coast, or least the other side of the frontline. In British airspace, and over territory the Germans did not control, he experienced a lack of radar interference. Schnaufer recalled that he could fly around as if it was peace time, since all British jamming and interference stopped immediately once he was in Allied airspace.

Last Victories – Further Combat Flying Stopped

On 7/8 March, he claimed three RAF four-engine bombers for victories 119 to 121. These were his last victories of the war. He was then banned from further combat flying and was given the task of evaluating the then new Dornier Do 335, a twin-engine heavy fighter with a unique “push-pull” layout, for its suitability as night fighter. Disobeying his ban from combat flying, he flew his last mission of the war on 9 April 1945. Attempting to chase a Lancaster, he took off from Faßberg Air Base at 22:00 and landed after 79 minutes at 23:19 without success.

Prisoner of War

Schnaufer was taken prisoner of war by the British Army in Schleswig-Holstein in May 1945. He was reportedly taken to England for interrogation. The British authorities were especially interested in knowing whether his achievements had been made under the influence of methamphetamine or other stimulating psychoactive drugs which induce temporary improvements in either mental or physical functions or both, as had been documented in widespread Wehrmacht use and made for the German military by the Temmler-Werke GmbH firm, under the name Pervitin. Schnaufer was released later that year in November following a bout of diphtheria. Some others have said that as per Rumpelhardt’s testimony, Schnaufer was never taken to England. Rumpelhardt was released on 4 August 1945 and soon after Schnaufer was admitted to a hospital in Flensburg, ill with a combination of diphtheria and scarlet fever. Interrogation had begun in late May 1945 by a team of twelve officers from the Department of Air Technical Intelligence (DAT), led by Air Commodore Roderick Aeneas Chisholm. The German prisoners were brought to Eggebek. Here they conducted a number of interviews with various members of the night fighter force.

The Winery Business

Following his release from the hospital and as a prisoner of war, Schnaufer took over the family wine business. He had never planned to run the family winery as his ambition had always been to pursue an officer’s career in the Luftwaffe. However, in the immediate aftermath of World War II the business had virtually ceased to exist and Schnaufer was given the task of rebuilding it from scratch. He had to re-establish business links to suppliers and customers and to consolidate them. Then he had to make new contacts in order to facilitate expansion and growth of the business. Lastly, he had to create an infrastructure which supported the growth of the business. His motto for business was clearly “Quality before Quantity”.

Failed Attempt To Go to South America

Soon the wine business began to prosper, Schnaufer also gave thought to alternative employment possibilities in peacetime aviation. With his wartime friend Hermann Greiner, he traveled from Weil am Rhein to Bern in Switzerland to meet South American diplomats; the two hoped to find employment as pilots in South America. To get to Bern, they crossed the Swiss-German border illegally. The meeting was a failure. As they attempted to make a second illegal border crossing to return to Germany they were caught by Swiss border guards. The Swiss handed them over to the French occupation authorities and they were imprisoned in Lörrach, where they remained until Schnaufer managed to make contact with a French general, who was a customer of the Schnaufer winery and had them released. This misadventure kept him away from his business for about half a year.

Dies After a Car Accident

In July 1950, Schnaufer was on a wine buying visit to France. On the afternoon of 13 July, he was heading south on the Route Nationale No. 10 in his Mercedes-Benz 170 convertible with a registration number “AWW 44-3425”. Just south of Bordeaux, at about 18:30, he was involved in a collision with a Renault 22 truck. The accident occurred at the intersection of road D1, present-day D211, and the N10, present-day D1010, in Cestas (44°42′04″N 0°42′20″W). The truck, driven by Jean Antoine Gasc, was carrying 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons) of empty gas cylinders. The collision ruptured the fuel tank of the Mercedes and ignited the petrol. Witnesses to the accident quickly put out the flames. Alice Ducourneau gave first aid to Schnaufer, who was bleeding from a wound from the back of his head. The police appeared at the scene of the accident at about 19:30, followed by an ambulance shortly thereafter. Schnaufer had suffered a fractured skull, and was immediately taken to the Saint-André Hôpital in Bordeaux.

Schnaufer never regained consciousness and succumbed to his injuries at the hospital two days later on 15 July 1950. The investigation into the accident concluded that though the impact of the two vehicles was severe, it seemed unlikely that the collision itself was the cause of his injuries. It was speculated that at least one of the truck’s cargo of 30 empty gas cylinders, which were thrown off by the collision, had struck Schnaufer on the head. Subsequently, the truck driver was charged with manslaughter and breach of traffic regulations before a court at Jauge, Cestas. The hearing began on 29 July 1950 and concluded with his conviction on 16 November 1950. Gasc was found guilty of not yielding the right of way, and his speed was considered too high. It was ruled that as a consequence of not observing the law, he involuntarily caused the death of Schnaufer. Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer is buried on the local cemetery of Calw, along the wall.

Summary of Aerial Victories

Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer was the top-scoring night fighter pilot of World War II. He was credited with 121 aerial victories claimed in just 164 combat missions. His victory total includes 114 RAF four-engine bombers; arguably accounting for more RAF casualties than any other Luftwaffe fighter pilot and becoming the third highest Luftwaffe claimant against the Western Allied Air Forces. His flight book indicated 2,300 sorties and 1,133 flying hours. Matthews and Foreman, authors of “Luftwaffe Aces — Biographies and Victory Claims”, researched the German Federal Archives and found documentation for 119 nocturnal aerial victory claims, plus three further unconfirmed claims.

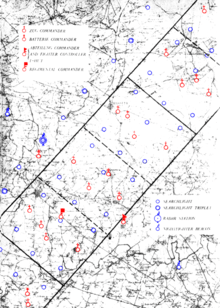

Until late 1944, Schnaufer documented his aerial victories with detailed geographical locations. After this date, he claimed his victories over territory occupied by the Allies, and his victories were logged in a Planquadrat (grid reference). The grid map was composed of rectangles measuring 15 minutes of latitude by 30 minutes of longitude, an area of about 360 square miles (930 km2).

Post War Recognition

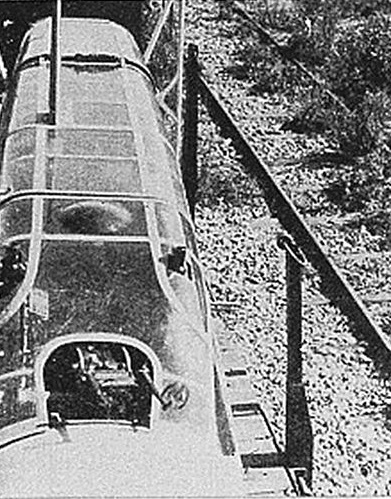

Schnaufer’s Messerschmitt Bf 110 G-4/U 8 was brought to England after the war. The aircraft was displayed in London’s Hyde Park. The port-side vertical stabiliser of this twin tailed aircraft, tallying all his victories, is preserved at the Imperial War Museum in London. A fin from another Bf 110 flown by Schnaufer is at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The street “Heinz-Schnaufer-Straße” in Calw was named after him.

Summary of Awards

- Front Flying Clasp of the Luftwaffe for Night Fighters in Gold

- Combined Pilots-Observation Badge

- Wound Badge in Black

- Iron Cross (1939)

- 2nd Class (2 June 1942)

- 1st Class (19 October 1942)

- Honour Goblet of the Luftwaffe on 26 July 1943

- German Cross in Gold on 16 August 1943.

- Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

- Knight’s Cross on 31 December 1943

- 507th Oak Leaves on 24 June 1944

- 84th Swords on 30 July 1944

- 21st Diamonds on 16 October 1944

With so many great men it’s a small wonder that Germany lost the war!!!

As they say Good die young. These legends should be very Inspiring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Germany had great fighters, and many heroes. Their lives are most inspiring stories full of innovative combat tactics. Germany lost the war because Hitler opened too many fronts and made many enemies

LikeLike

Fascinating to say the least. Flying predominantly by night takes its toll on the body and to do it night after night for years together in the world’s most hostile combat environment, takes raw courage and guts. He was all of 23 years old at the end of the war.

What is even more amazing is the kind of record-keeping and tracking of enemy pilots and their details done by both sides. The Brits actually had all the accurate details of Schnaufer, as quoted “The British propaganda radio station (Soldiers’ Radio Calais) congratulated Schnaufer on his 23rd birthday on 16 February 1945. The radio station explicitly addressed the soldiers of NJG 4 stationed in Gütersloh followed by the song “The Bogeyman” praising him for the honorary title given to him by the British bomber crews “The spook of St. Trond“. All this in an era where and when there was no “hi-tech” capability. Fascinating is the word. Maybe, just maybe there are lessons to be learnt on “work-culture”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely. Very professional. Very interesting night interception tactics, and that upward firing gun. Very inspiring stories of very successful fighter pilots.

LikeLike