This month’s guestblog is written by Daniel Geary, the resident marine biologist at Atmosphere Resort in Dauin, Philippines. It’s safe to say that Daniel is very passionate AND knowledgeable about frogfishes. He’s been studying them for years in Dauin and even wrote (and teaches) a PADI speciality course on these awesome critters! In this blog he gives a taste of some of the many ways frogfish are fantastic and deserve a closer look.

This month’s guestblog is written by Daniel Geary, the resident marine biologist at Atmosphere Resort in Dauin, Philippines. It’s safe to say that Daniel is very passionate AND knowledgeable about frogfishes. He’s been studying them for years in Dauin and even wrote (and teaches) a PADI speciality course on these awesome critters! In this blog he gives a taste of some of the many ways frogfish are fantastic and deserve a closer look.

Longlure frogfish (Antennarius multiocellatus) from Florida

Frogfish. You have probably heard of them, and if you’re a diver you might have seen one or two before. You have definitely swam right past a few of them without knowing they were there. Although most of them have a face only a mother could love, behind this outer layer exists a well-adapted, expert fisherman with amazing camouflage capabilities. They are more than just a lazy, camouflaged blob that sometimes doesn’t change location for a year.

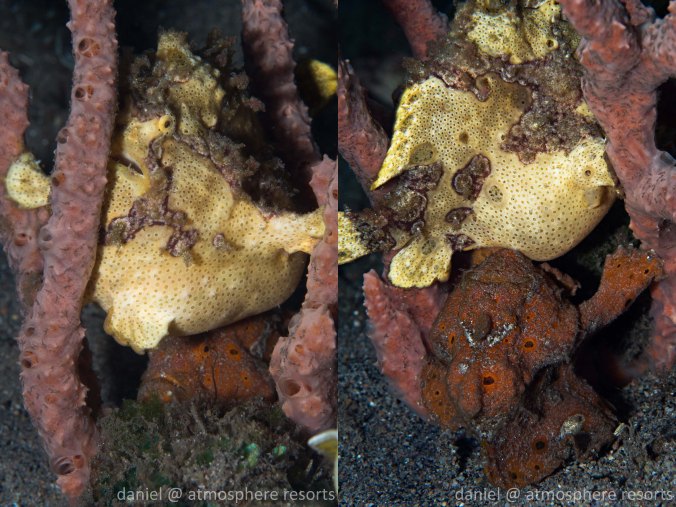

Frogfish are anglerfish, although they are what I call a shallow, less ugly version of anglerfish. They have a rod and a lure that they actively fish with when necessary. Their fins look like limbs that somewhat resemble those of a frog. They must inhale water though their mouth to then push it out of their gills which aids in locomotion. Frogfish are experts at changing color and can change color multiple times, usually to blend in with their surroundings. Normally a full color change takes about 2 weeks, but frogfish have been witnessed to change color in under ten seconds when disturbed by divers’ bubbles and needing to switch to a different coral.

The same giant frogfish (Antennarius commersoni) changing colour in two weeks

There are around 50 species of frogfish, with a new species or two being described every few years. Frogfish can be found worldwide in tropical and subtropical waters (but not in the Mediterranean). Some species are only found at a handful of dive sites, others are only found in one country or continent. A handful of species are found in the majority of the warm water areas, but only the Sargassumfish is found worldwide. There have been a few occasions where Sargassumfish were found all the way up in the cold waters of Norway and Rhode Island – way out of their preferred habitat, but they live their lives floating in seaweed and/or other debris and are at the mercy of the ocean currents.

Sargassum frogfish (Histrio histrio) often wash up on the shore of the Atmosphere housereef, when they do, they get released back into deeper water

Painted frogfish (Antennarius pictus) using its lure to attract prey

Frogfish are ambush predators which is why they seem to be so lazy. The less they move, the better predators they can become due to algae, coral polyps, and any other organisms that use the frogfish as habitat. I call this being lazily efficient, or efficiently lazy. Frogfish will make minimal adjustments to their body positioning before they begin to lure prey, although sometimes the frogfish are so camouflaged that they don’t need to actively attract prey. Frogfish swallow their prey whole by opening their mouth and creating an instant vacuum since the volume of the mouth increases up to twelve times the original amount. This means frogfish can swallow their prey whole in six milliseconds. They feed on a variety of organisms, depending on where the frogfish lives. Generally they like small fish like cardinalfish, shrimps and crabs, and sometimes other frogfish. They can comfortably swallow prey that is their own size, and with a bit of effort they can swallow prey up to twice their size, although this can result in the death of the frogfish if the prey item is too large and gets stuck in their throat. Frogfish do not have many predators, but they are sometimes preyed on by moray eels, triggerfish, and lizardfish. Flounder will sometimes suck up juveniles from the sand and fishermen in the Philippines have been known to capture and eat Giant Frogfish.

This giant frogfish (Antennarius commersoni) bit of more than it could chew and did not live to tell the tale. Photo taken at Apo Island

Frogfish egg raft

Frogfish have been known to eat each other if they get too close, especially after failed mating attempts. A male will approach a female when she is bloated with eggs. He will do his best to show off for her, which includes expanding his fins to their maximum sizes, rapidly opening and closing his mouth, as well as violently shaking his body. At this point, the female either accepts him or tries to eat him. If accepted, he gets to stand next to the female, which is the frogfish equivalent of holding hands. Once he is ready to mate, he will start again with his flashy moves, but this time bouncing around the female. Sometimes he has to physically swim her off the substrate to mate, other times she is able to swim on her own. Once they are a meter or two above the substrate, the female releases her egg raft, causing her to spin rapidly. The male then fertilizes this egg raft, also spinning rapidly. Both the frogfish then return to the bottom as the eggs float off into the distance. The eggs will hatch a few days later and become tiny planktonic frogfish babies, which will continue to float for a month or two until they are big enough to settle in the substrate, change color, and begin their lives as adorable frogfish.

A male (red) painted frogfish (Antennarius pictus) trying to convince the female (yellow) to mate

Stay tuned for more frogfish insights coming in December, where I’ll write about the history of frogfish research and describe a handful of frogfish species, including a potentially “new” species. Until then, keep an eye for frogfish on all your dives, especially if you’re in warm water.

Pingback: Guestblog: Frogfish history | Critter Research

Pingback: Critter Research

Pingback: Ambon and Halmahera fieldwork: Mini-blog 3 – Surveying Ambon’s reefs | Critter Research

Pingback: Fieldwork discoveries in corona times: Alor | Critter Research