Category: Videogame Consoles

Sega Saturn

This is my Sega Saturn, which I bought used at The Record Exchange (now simply The Exchange) on Howe Rd. in Cuyahoga Falls in October 1999.

I know this because I saved the date-stamped price tag by sticking it on the Saturn’s battery door.

The Saturn was Sega’s 32-bit game console, a contemporary of the better known Nintendo N64 and the Sony PlayStation. It lived a short, brutish existence where it was pummeled by the PlayStation. In the US the Saturn came out in May 1995 and was basically dead by the end of 1998.

The Saturn was the first game console that I truly loved. Keep in mind that I bought mine after the platform was dead and buried and used game stores were eager to unload most of the games for less than $20. If I had paid $399 for one brand new in 1995 with a $50 copy of Daytona USA I might have different feelings.

The thing that makes the Saturn intensely interesting is how it was simultaneously such a lovable platform and a disaster for Sega. It’s a story about what happens when executives totally misunderstand their market and what happens when you give great developers a limited canvas to make great games with and they do the best they can.

When you look at the Saturn totally out of it’s historical context and just look at on it’s own, it’s a fine piece of gaming hardware. Compared to the Sega CD it replaced the quality of the plastic seems to have been improved. The Saturn is substantial without being outrageously huge. The whole thing was built around a top-loading 2X CD-ROM drive.

It plays audio CDs from an on-screen menu that also supports CD+G discs (mostly for karaoke).

It has a CR2032 battery that backs up internally memory for saving games, accessible behind a door at the rear of the console.

It has a cartridge slot for adding additional RAM and other accessories like GameSharks.

There were several official controllers available for it during it’s lifetime.

The two I own are the this 6 button digital controller:

And the “3D controller” with the analog stick that was packaged with NiGHTS:

You can see the clear family resemblance to the Dreamcast controller.

My Saturn is a bit odd because at some point the screws that hold the top shell to the rest of the console sheared off.

That’s not supposed to happen. All that’s holding the two parts of the Saturn together is the clip on the battery door. Fortunately this gives me an excellent opportunity to show you what the inside of the Saturn looks like:

Despite all of this, my Saturn still works after at least 15 years of service.

I should explain why I was buying a Saturn for $25 at The Record Exchange in 1999. You might say that several decisions by my parents and misguided Sega executives led to that moment.

My parents never bought my brother and I videogames as children. I’m not sure if they thought games were time wasters or wastes of money. Or, it could have just been they didn’t have any philosophical problem with them but they were uncomfortable buying a toy more expensive than $100. Whatever the reason we didn’t have videogames. Considering how many awful games people dropped $50 on in the pre-Internet days when there was so little information about which games were worth buying, I can see their point. I also know now that there were plenty of perfectly good games that were so difficult that you might stop playing in frustration and never get your money’s worth out of them.

Instead, videogames were something I would only see at a friend’s house…and when those moments happened they were magical.

I can’t speak for women of my generation but at least for a lot of males of the so-called “Millennial generation” videogames are to us what Rock ‘n Roll was to the Baby Boomers. They are the cultural innovation that we were the first to grow up with and they define us as a generation. If you’re looking for particular images that define a generation and I say to you “Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock” you think Baby Boomers. If I say to you “Super Mario Bros.” you think Millennials.

By 1996 or so I was pretty interested in buying some sort of videogame console, but I was somewhat restricted in what I could afford. The first game system I bought was a used original Game Boy in 1996. However, shortly after that my family got a current PC and my interests shifted to computer games: Doom, Quake, etc, which is what eventually led to the Voodoo 2.

By 1998 I noticed how dirt cheap the Sega Genesis had become so my brother and I chipped in together to buy a used Genesis (which I believe we bought from The Record Exchange). I quickly found that I did enjoy playing 2D games but I was really enjoying the 3D games I was playing on PC.

Sega did an oddly consistent job of porting their console games to PC in the 1990s, so I had played PC versions of some of the games that came out on Saturn in the 1995-1998 timeframe including the somewhat middling PC port of Daytona USA

So in 1999 when I came across this used Saturn for a mere $25 at The Record Exchange, I was eager to buy it.

But why was the Saturn $25 when a used PlayStation or N64 was most likely going for $80-$100 at the same time?

As I noted in the Sega Genesis Nomad post, Sega was making some very strange decisions about hardware in the mid-1990s. At that time Sega was at at the forefront of arcade game technology. Recall that in the Voodoo 2 post I said that if you sat down at one of Sega’s Daytona USA or Virtua Fighter 2 machines in 1995 you were basically treated to the most gorgeous videogame experience money could by at the time. That’s because Sega was working with Lockheed Martin to use 3D graphics hardware from flight simulators in arcade machines.

At the same time as they were redefining arcade games Sega was busy designing the home console that would succeed the popular Genesis (aka the console people refer to today as simply “the Sega”). Home consoles were still firmly rooted in 2D, but there were cracks appearing. For example, Nintendo’s Star Fox for the Super Nintendo embedded a primitive 3D graphics chip in the cartridge and introduced a lot of home console gamers to 3D, one slowly rendered frame at a time. Sega pulled a similar trick with the Genesis port of Virtua Racing, which embedded a special DSP chip in the cartridge (you may remember this from the Nomad post):

Sega decided on a design for the Saturn which would produce excellent 2D graphics with 3D graphics as a secondary capability. The way the Saturn produced 3D was a bit complicated but basically it could take a sprite and position it in 3D space in such a way that it acted like a polygon in 3D graphics. If you place enough of these sprites on the screen you can create a whole 3D scene.

I can see in retrospect how this made sense to Sega’s executives. People like 2D games, so let’s make a great 2D machine. They also must have considered that 3D hardware on the same level as their arcade hardware was not feasible in a $400 home console.

However, Sega’s competitors didn’t see things that way. Sony and Nintendo both built the best 3D machines they could, 2D be damned. One would expect their did this largely in response to the popularity of Sega’s 3D arcade games.

The story that’s gone around about Sega’s reaction to this is that in response they decided to put a second CPU in the Saturn. I have no idea if that’s why the Saturn ended up with two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs, but it would make sense if was an act of desperation.

Having two CPUs is one of those things that sounds great but in reality can turn into a real mess. A CPU is only as fast as the rest of the machine can feed it things to do. If say, one CPU is reading from the RAM and the other can’t at the same time, it sits there idle, waiting. There are also not that many kinds types of work that can easily be spread across two CPUs without some loss in efficiency. If the work one CPU is doing depends on work the other CPU is still working on the first CPU sits there idle, waiting. These are problems in computer science that people are still working furiously on today. These were not problems Sega was going to solve for a rushed videogame console launch 19 years ago.

The design they ended up with for the Saturn was immensely complicated. All told, it contained:

- Two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs

- One graphics processor for sprites and polygons (VDP1)

- One graphics processor for background scrolling (VDP2)

- One Hitachi SH-1 CPU for CD-ROM I/O processing

- One Motorola 68000 derived CPU as the sound controller

- One Yamaha FH1 sound DSP

- Apparently there was another custom DSP chip to assist for 3D geometry processing

That’s a lot of silicon. It was expensive to manufacturer and difficult to program. The PlayStation, which started life at $299, had a single CPU and a single graphics processor and in general produced better results than the Saturn.

Sega had psyched itself out. Here the company that was showing everyone what brilliant 3D arcade games looked like failed to understand that they had actually fundamentally changed consumer expectations and built a game console to win the last war, so to speak.

When the PlayStation and N64 arrived they ushered in games that were built around 3D graphics. Super Mario 64, in particular made consumers expect increasingly rich 3D worlds, exactly the type of thing the Saturn did not excel at.

Sega had gambled on consumers being interested in the types of games they produced for the arcades: Games that were short but required hours of practice to master. By 1997-1998 consumers’ tastes had changed and they were enjoying games like Gran Turismo that still required hours to master but offered hours of content as well. 1995’s Sega Rally only contained four tracks and three cars. 1998’s Gran Turismo had 178 cars on 11 tracks.

Sega’s development teams eventually adapted to this new reality but it was too late to save the doomed Saturn. Brilliant end-stage Saturn games like Panzer Dragoon Saga and Burning Rangers would never reach enough players’ hands to make a difference.

For the eagle eyed…This is a US copy of Burning Rangers with a jewel case insert printed from a scan of the Japanese box art.

By Fall-1999 the Saturn was dead and buried as a game platform. Not only had it failed in the marketplace but it’s hurried successor, the Dreamcast, was now on store shelves. That’s why a used Saturn was $25 in 1999.

The thing was that despite the fact that the Saturn had failed, the games weren’t bad, and since I was buying them after the fact they were dirt cheap. I accumulated quite a few of them:

Oddly enough, my favorite Saturn game was the much criticized Saturn version of Daytona USA that launched with the Saturn in 1995.

The original Saturn version of Daytona USA was a mess. Sega’s AM2 team, who had developed the original arcade game had been tasked with somehow creating a viable Saturn version of Daytona USA. The whole point of the game was that you were racing against a large number of opponents (up to 40 on one track). The Saturn could barely do 3D and here it was being asked to do the impossible.

The game they produced was clearly a rushed, sloppy mess. But it was still fun! The way the car controls is still brilliant even if the graphics can barely keep up. I fell in love with Daytona. Later Sega attempted several other versions of Daytona on Saturn and Dreamcast but I vastly prefer the original Saturn version, imperfect as it may be.

Another memorable game was Wipeout. To be honest, when I asked to see what Wipeout was one day at Funcoland I had no idea that the game was a futuristic racing game. I thought it had something to do with snowboarding!

Wipeout was a revelation. Sega’s games were bright and colorful with similarly cheerful, jazzy music. Wipeout is a dark and foreboding combat racing game that takes place in a cyberpunk-ish corporate dominated future. I still catch myself humming the game’s European electronica soundtrack. The game used CD audio for the soundtrack so you could put the disc in a CD player and listen to the music separately if you wished. Wipeout was the best of what videogames had to offer in 1995: astonishing 3D visuals and CD quality sound.

From about 1999 to 2000 I had an immense amount of fun collecting cheap used Saturn classics like NiGHTS, Virtua Cop, Panzer Dragoon, Sonic R, Virtua Fighter 2, Sega Rally, and others…As odd as this is to say, the Saturn was my console videogame alma mater.

Today I understand that something can be a business failure but not a failure to the people who enjoyed it. To me, the Saturn was a glorious success and I treasure the time I have had with it.

SNK NeoGeo Pocket Color

This is my NeoGeo Pocket Color (NGPC), a short-lived handheld videogame system that the somewhat esoteric Japanese company SNK sold from 1999-2001.

I believe I found it at Village Thrift sometime well after the system was discontinued in the United States in 2000.

Village Thrift has a good habit of taking a lot of items that go together, like a NGPC and several games, and putting them together in a clear plastic bag. I remember finding it at their showcase, rather than the electronics section.

I’m also not sure if the scratch on the screen was there when I bought it or if that happened later.

The games that were in that plastic bag along with the NGPC were:

Sonic The Hedgehog Pocket Adventure, a Sonic the Hedgehog platformer:

Bust-A-Move Pocket, an entry in the well-known puzzle game series that resembles Bejeweled:

Baseball Stars Color, a fairly straightforward baseball game:

Neo Dragon’s Wild, a collection of “casino” games:

Metal Slug 1st Mission, a portable version of SNK’s Rambo-like side scrolling platforming shooter:

And finally Metal Slug 2nd Mission, the sequel to Metal Slug 1st Mission:

Oddly enough, there were no fighting games in that lot because that’s what SNK was known for and what enthusiasts wanted the NGPC for.

There are several neat and interesting things about the NeoGeo Pocket Color hardware. The first is that it has this tiny spec sheet for the display written above the screen.

You know, in case you ever need to look up it’s pixel pitch.

The screen on the NGPC can be difficult to see in all but direct sunlight and it can also be a pain to photograph. So, if my screenshots look odd, that’s why.

The need for very bright light in order to see the colors well was a problem with a lot of the color portable systems of this time period. I fondly remember the uncomfortable position I had to sit in to play Tetris DX on my purple Game Boy Color while hunched below a reading light that was attached to my bed. Penny Arcade memorably poked fun of the difficult to see screen on the Game Boy Advance in 2001. The rise of back-lit screens like the one on my Game Boy Micro finally alleviated this problem.

The unfortunate thing is that when you see screenshots of games from the NGPC and Game Boy Color from emulators you realize what beautiful colors those games were putting out and how the hardware made them almost impossible to see.

The NGPC has a unique 8-way joypad located on the left side of the console. This was the system’s most memorable feature and one that people would be wishing for on other portable game systems for years afterword.

Unlike the control stick you might see on an XBox controller this is a digital control pad, rather than an analog one. However, because it can move in eight directions it’s easier to point in a diagonal direction than a conventional cross-shaped D-pad like you find on Nintendo systems. SNK specialized in 2D arcade games that had sophisticated joysticks so it’s no surprise to find something like this on their portable system. The joypad has a really solid feel and makes a lovely clicking sound as you move it around.

On the back the NGPC curiously has two battery covers. The system uses two AA batteries to power the system and one CR2032 button battery to backup memory to save games and settings.

If the CR2032 dies you get this lovely warning message when you turn off the console.

When you turn on the NGPC the boot screen has an attractive little animation accompanied by a cute little tune.

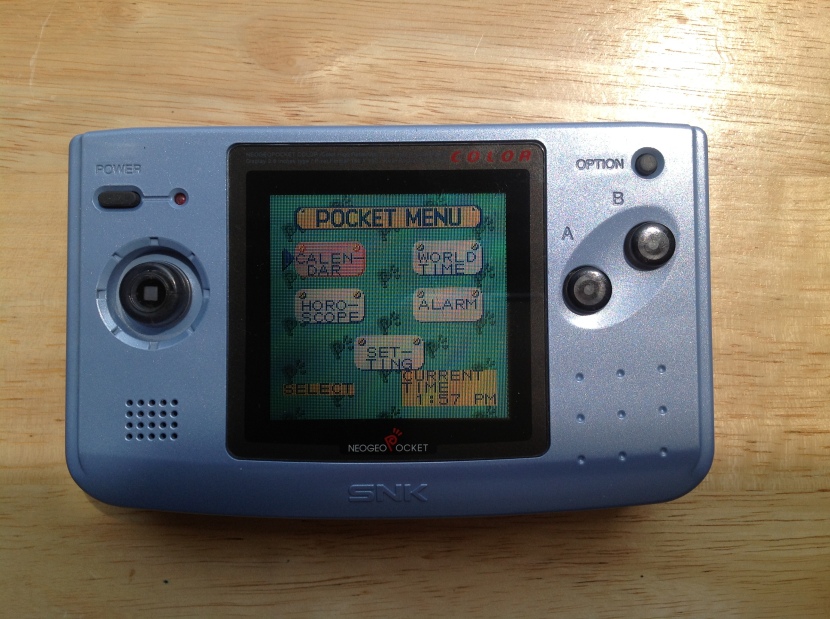

If you turn on the NGPC without a cartridge you get this menu screen that includes a calendar and (in silly Japanese fashion) a horoscope.

I can’t think of a videogame feature more utterly useless than a horoscope.

In order to explain the NeoGeo Pocket Color I have to tie together a few threads.

SNK is not what you would call a household name in the US but it was one of the titans of the Japanese arcade in the 1980s and 1990s. Their specialty was (and still is) was 2D fighting games. That is to say that the graphics are hand-drawn sprites that view the action from the side.

In 1990 SNK released the NeoGeo home console which for all intents and purposes was one of their arcade machines repackaged for home use. As you would expect it was outrageously expensive. The console itself (including a pack-in game) was $650 and games cost $200.

If you owned a Sega Genesis or a Nintendo SNES the NeoGeo must have seemed like some sort of mystical Shangri-La.

If you purchases a NeoGeo what you would have gotten for your obscene amount of money were perfect arcade games in the home. From the beginning of the home console market the fidelity of home console conversions of arcade games had been a constant problem. There were always compromises in animation, music, fluidity, and control sensitivity. Not so, if you were a NeoGeo owner. What you got was perfection.

But in the mid-1990s the market moved on to consoles such as the PlayStation and N64 that were built around 3D graphics. The arcades moved on too, and fighting games like the Tekken and Virtua Fighter series that were built on 3D graphics excited the public’s imagination.

SNK’s contemporaries like Capcom (whose Street Fighter series is one of the pillars of the 2D fighting genre) found ways to stay relevant by developing new series like Resident Evil while continuing their line of 2D fighting games. SNK didn’t and the NeoGeo became an expensive collector’s item.

Then, something possessed SNK to release a monochrome portable system called the NeoGeo Pocket in 1998 followed by the NeoGeo Pocket Color in 1999.

1999, when the NGPC came out, was a very strange time for portable videogames because it’s when the technological gap between the home consoles and portable consoles was at it’s peak. It wasn’t so much a technological gap as it was a chasm.

It’s funny how technology trends wax and wane over decades. Today, vast sums of R&D dollars are being spent on making components (especially CPUs and GPUs) for portable electronics faster and more power efficient. Intel’s new (Jone 2013) Haswell processors have marginal speed gains for desktop users but offer better battery life and less heat for mobile users. Across the industry from Apple to Samsung the effort is going into making better mobile devices.

Back in 1999, everything was different. Back then the money was being put into chips for devices like PCs and home game consoles that were plugged into the wall. We wanted faster devices and didn’t much care how much power they used or how much heat they put out.

In the home console market, the Dreamcast had just debuted, ushering in an era of more more refined 3D graphics that would lead to the PS2, XBox, and GameCube.

The Dreamcast was powered by a 32-bit Hitachi SH-4 RISC CPU and a PowerVR GPU that’s the direct ancestor of the GPU in today’s iPad and PS Vita.

Meanwhile in the portable realm the popular Game Boy Color was still based on an 8-bit CPU, technology that was solidly rooted in the game consoles of the 1980s. Very roughly this meant that the state-of-the-art home console was at least several hundred times more powerful than the leading portable console.

Battery life was the root cause of this gap. You could build a much more powerful portable system with a much more powerful CPU, much more RAM, and a higher resolution back-lit screen. But, it would have been heavy and had horrendous battery life. The marketplace thrashings that the Atari Lynx, the NEC TurboExpress, the Sega Game Gear, and the Sega Genesis Nomad received at the hands of the Game Boy throughout the 1990s were all clear proof of this reality.

Essentially those systems had tried to be to the Game Boy what the NeoGeo had been to the SNES and the Genesis, a far more powerful, far more expensive competitor. But, there was no place for that in the portable market.

The breakthroughs that would happen in the mid-2000s that allowed the revolution in portable computing devices simply had not occurred yet.

In 1999 the Game Boy Color sat at the sweet spot between battery life, weight/size, and cost. As a result, any serious competitor would have to have a comparable size, weight, cost, and battery life to the Game Boy Color and that precluded anything that was vastly more powerful. But it would also make it difficult for a serious competitor to differentiate itself from the Game Boy.

Technically, the NGPC was a 16-bit system and the Game Boy Color was just an 8-bit system but at these CPU speeds, with these amounts of RAM, and with these screens, the difference was negligible.

So the situation you had was that SNK must have felt that their background in 2D arcade games would be an asset in portable games, which were still totally dominated by 2D graphics even as the home consoles were putting out increasingly sophisticated 3D graphics. They probably also thought that as a company that specialized in fighting games they could build a portable game system suited to fighting games (with that gorgeous 8-way joypad) and exploit a market that Nintendo had ignored.

The problem was that 1998-1999 was an awful time for any company not named Nintendo to launch a handheld game console. From the earliest days of the Game Boy most of the best games had been essentially miniature versions of console games. The great games of the Game Boy from 1989 to 1998 include Super Mario Land 1 and 2, Metroid II, Legend of Zelda: Links’ Awakening, Kirby’s Dream Land, the Donkey Kong Land series and other games that basically would not have existed without their console counterparts.

Pokemon changed all of that in 1998 (in the US). Here was a game that had no console counterpart. Here was a game who’s popularity was strongly attached to being able to play the game against and with friends by connecting your Game Boys together. Here was a game that lent itself to consuming every available hour of a child’s day –on the school bus, on the playground, waiting at the doctor’s office, etc — like no game since Tetris.

NGPC had nothing comparable to Pokemon. At the time, the influence of SNK’s 2D arcade games was waning in American arcades so for the vast portion of the NGPC’s potential audience they had very little to offer. There were SNK enthusiasts who loved the NGPC and there were fighting game enthusiasts who loved the NGPC, but on the whole it didn’t make much headway in the American market. And that’s why mine ended up at a thrift store a few years later.