A scientist from the University of Costa Rica believes he may be on the trail of discovering a new antibiotic hidden in the fur bacteria of sloths, mammals living in the tropical forests of Central America that never get sick.

"When we look at the fur of sloths, we see movement: moths, various types of insects, and obviously when there is a cohabitation of numerous types of organisms there must be a system that controls them," says Kavaria, reports N1.

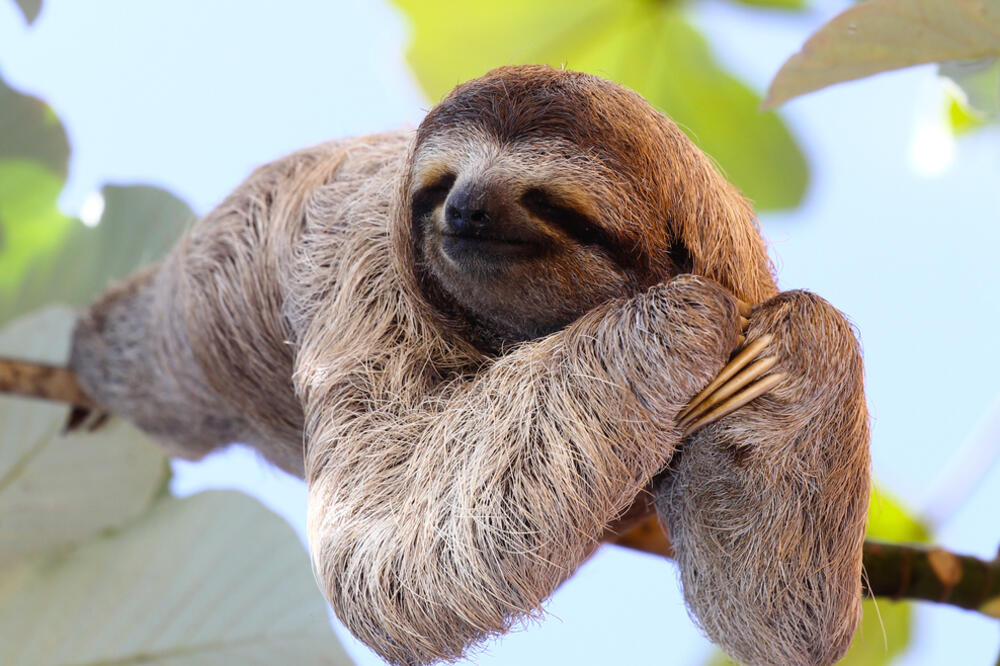

Sloths carry a unique biotype of insects, algae and bacteria in their fur that appears to protect them from disease, says scientist Max Kavaria.

In his research, which he has been conducting since 2020, he proved that "those microorganisms are capable of producing antibiotics that enable the regulation of pathogenic agents in the fur of sloths."

"These are bacteria from the genus Rothia and Brevibacterium", says the scientist who published the results of the study in the scientific journal Environmental Microbiology.

Now it is important to investigate whether these antibiotics have a future in the pharmacopoeia for humans, he said.

Sloths, the two species of which live in Costa Rica - Bradypus variegatus or three-toed sloth, as well as Choloepus hoffmanni or two-toed sloth - live in the trees of tropical forests in Central America, and also on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica in a humid climate with temperatures from 22 to 30 degrees Celsius.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature believes that the population of these peaceful mammals - which also live in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru and Venezuela - is declining.

In Costa Rica, American Judy Avey manages the Sloth Sanctuary in Cahuita, which she founded with her late husband, Luis Arroyo, to care for injured animals.

A thousand sloths saved

Judy Avey previously lived in Alaska and didn't even know sloths existed before coming to Costa Rica. In 1992, the couple took care of the first sloth, which they named "Buttercup", and since then a thousand individuals have passed through their sanctuary.

So Max Cavaria approached Judy to study sloths that had died on high-voltage power lines or been run over by a car or injured by dogs or found motherless cubs.

"We never received a sick sloth, some were burned by high-voltage wires and had injuries on their hands, but no infection occurred," points out Judy Avey.

Max Kavaria cut the hair of 15 individuals of each of the two species and cultured them in the laboratory to study them.

After three years of research, he counted twenty "candidates" for the production of antibiotics, but it remains to be seen whether it is possible to apply them to the human species.

"We need to understand the system (that produces immunity in sloths) and which molecules participate in it," he explained.

After all, nature is the first of all laboratories, Kavaria points out and reminds us of penicillin, which was discovered in 1928 by Alexander Fleming, winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945, from fungi that naturally synthesize that antibiotic.

The discovery of new antibiotics is a major challenge today as the World Health Organization warns that current antibiotic resistance could cause 10 million deaths each year by mid-century.

"That's why projects like ours can help the development of new molecules that could be used in the short or long term in the fight against antibiotic resistance", says Max Kavaria.

Bonus video: