By Randi Bjornstad

For the past two decades, much of Eugene writer Faris Cassell’s life has been dominated by a Holocaust mystery that started with a letter given to her physician husband, Sidney Cassell, by an elderly patient whose aunt and uncle had received it more than a half-century before from someone they didn’t even know.

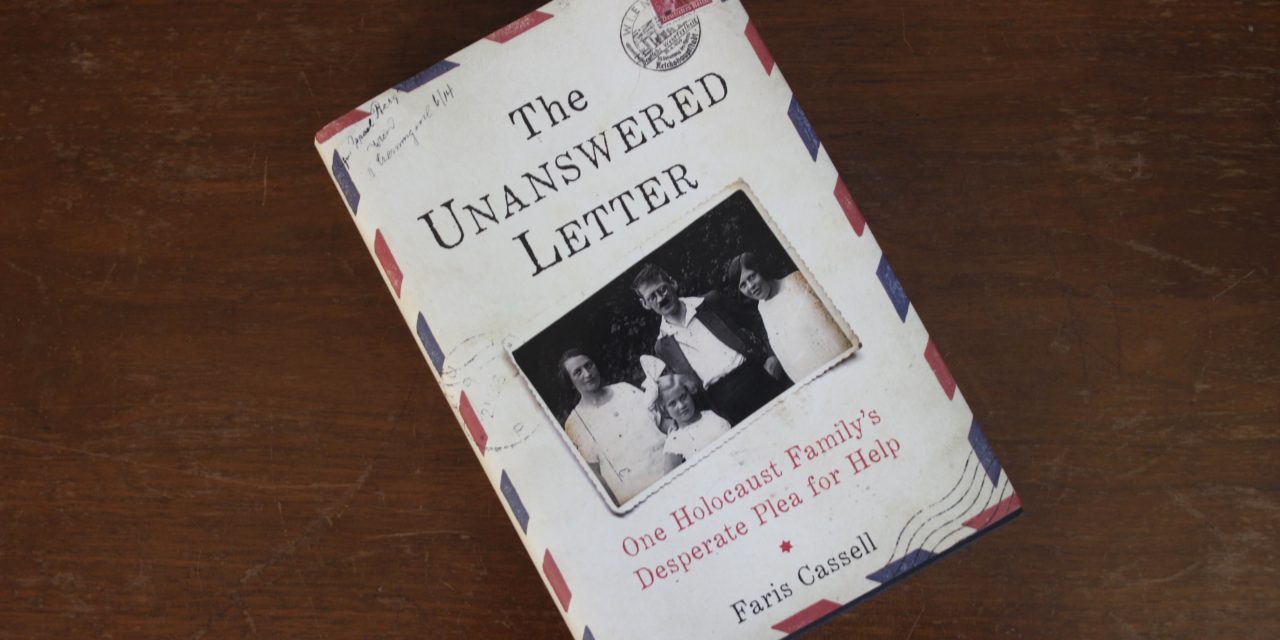

Faris Cassell, author of The Unanswered Letter

It ended with a 400-page hardbound book, The Unanswered Letter: One Holocaust Family’s Desperate Plea for Help, that was published in 2020 and now is being released in paperback.

“I first saw the letter when Sidney brought it home with him in 2000, and I knew it was going to raise a lot of questions,” Cassell recalled. “I was so curious about it. I asked him to find out if I could meet the person who had given it to him. She was elderly and in ill health, and apparently she felt it was time to put her affairs in order.”

The woman, whose name was Margaret, had been on the verge of throwing the letter away, Cassell said, but her daughter urged her to save it because it already had been preserved by their relatives for many years, even through several moves.

Margaret saved the letter, but first she cut off the stamp — she belonged to a church group that did stamp collecting and selling — before eventually giving the letter to Dr. Cassell.

“It is fortunate that this happened when letters were still physical things,” Faris Cassell said. “Back then it meant something to sit down and write, send, and receive letters. I felt that strongly when I first held that letter in my hand. In all those decades, few people had read it or even touched it.”

All the same, there was so much more to be known: Did the Bergers in California ever respond to the Bergers in Vienna? If they did and never heard back, did they keep it in hopes of hearing something later? If they didn’t, did they save the letter out of guilt that they did not try to help?

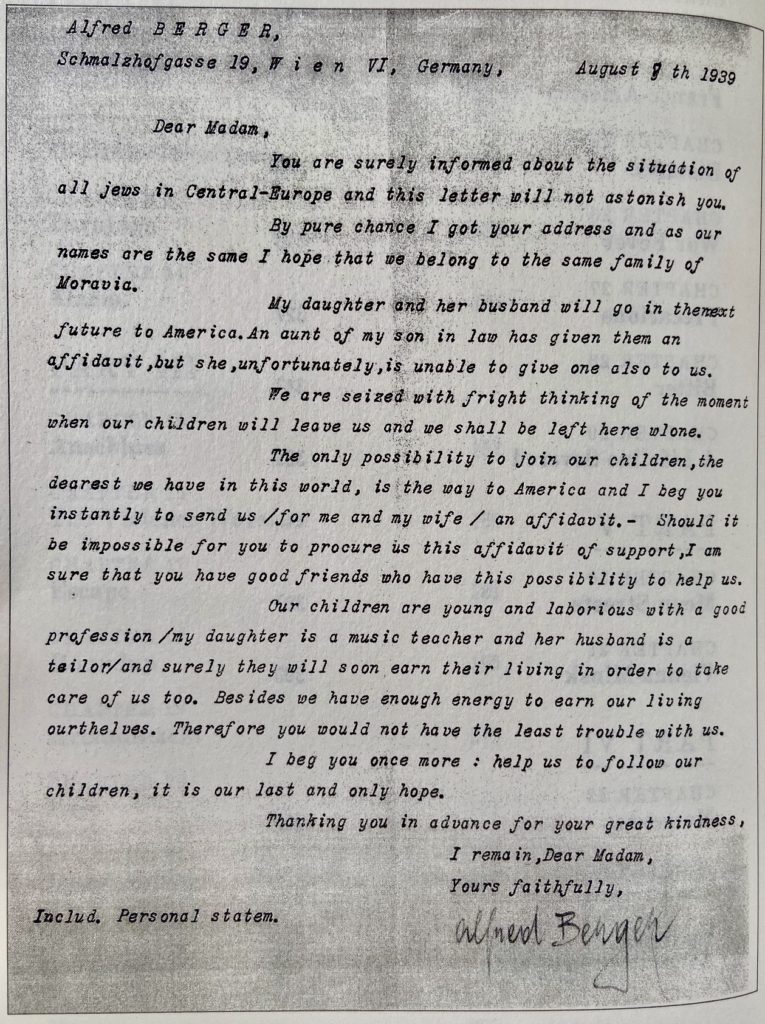

You are surely informed about the situation of all jews in Central-Europe and this letter will not astonish you, Alfred Berger had written. By pure chance I got your address and as our names are the same I hope that we belong to the same family of Moravia.

He went on to explain that while relatives in the United States had assisted one of his daughters and her husband with an affidavit of support to emigrate, he and his wife had not been able to find anyone to help. We are seized with fright thinking of the moment when our children will leave us and we shall be left here alone …. I beg you once more: help us to follow our children, it is our last and best hope.

When Cassell asked her husband why Margaret chose to give him the letter, he said, “I may have been the only Jewish person she knew.”

Faris Cassell is not Jewish, but the minute she read the letter, she was determined to find out why Alfred Berger had written such a desperate message in August 1939 on behalf of himself and his wife, Hedwig, addressed to people in the United States that he did not know, apparently for the simple reason that they had the same last name, and, if they would, could sponsor the Viennese Bergers in their quest to emigrate to the United States.

She wanted to know what eventually happened to the Austrian Bergers, and she wondered why the American Bergers had kept the letter all those years, even though they were not Jewish, had no personal experience of the Holocaust that killed 6 million European Jewish people, and did not render assistance.

Cassell’s search for answers led her on an odyssey that took upwards of 20 years, thousands of miles of travel throughout the United States and Europe, and considerable sleuthing into records and memories to ferret out the truth of what had happened to the elder Bergers. Along the way, she met members of their family and sat in places where they had lived even as their very lives fell prey to the horror of Adolf Hitler’s “final solution” that hinged on extermination of Jewish people from Europe.

The Unanswered Letter is an exhaustive compendium of historical, political, and familial facts. In some ways it’s as much textbook as narrative, except that as it proceeds to document the machinations of the atrocities of the German government up to and through World War II in great detail, it also shows the result in the form of the successes and failures of this one real extended family to escape the horror of the Third Reich.

Cassell, who already had considerable experience writing reviews of other authors’ books, had to find her own way in crafting this one.

“I had a lot of learning to do on how to write longer, and I didn’t know how to structure something with so many characters, facts, and themes of good and evil such as all the terrible regulations imposed on the Jewish people as time went on,” she said. “I was realizing how different those two approaches were — what was happening politically and what was happening with people — so I ended up making two parallel timelines so I could continually compare the people and the political situation and make sure I wasn’t missing something.”

She’s also come to some conclusions about human nature in general through the process of researching and writing The Unanswered Letter.

“I can see that justice is something that if people are apathetic about, things will go off track, and the more it is allowed to happen, the more it will happen and the worse it will be,” Cassell said. “There were many people back then who did not like what was happening in Europe and to the Jewish people, but Hitler’s power relied on fear and brutality, and while people tried to do the right things as individuals, they had to remain hidden or be destroyed by the dictatorship.”

In the end, neither Alfred nor Hedwig Berger survived World War II. He died of an apparent accident in 1942, and shortly afterward, she was deported to a concentration camp, where she died.

In a way, Cassell feels that she was “called to do their story.”

“It came to me. It sat with me until I had time to start reading and learning about something I really didn’t know much about. Up until then, my idea of what had happened to the Jewish people was mostly limited to concentration camps and Anne Frank.”

Was it coincidence that Cassell’s husband was the one to receive the letter? “Who knows?” she said. “When it came to me, I didn’t feel ‘chosen,’ but I did feel that it was my responsibility. I felt that if I didn’t do something, nobody would ever know. The story about this family would be lost, and Alfred and Hedwig Berger would be lost a second time.”

Title: The Unanswered Letter — One Holocaust Family’s Desperate Plea for Help

Author: Faris Cassell

Publisher: Regnery History, imprint of the Salem Media Group, Washington, D.C.; 2020

Awards: 2020 National Jewish Book Award in the Holocaust category; 2021 American Society of Journalists and Authors, first place in the History category; 2020 Pacific Northwest Writers’ Association in the Prepublication Manuscript category

Alfred Berger’s plea for help, sent from Vienna in 1939 to a family in California with the same last name