So You Want to Learn Science? Pt 2 - The Brain, a Beginner's Manual.

In Science (and elsewhere) there can be so much to learn that we may often forget things, miss them entirely as we go along (just a few months ago I googled, ‘what even is fire?’, I kid you not) and face difficult problems that can seem insurmountable at first, so it helps to make our learning as efficient as possible. Like anything else, our brain is a tool that works along very specific guidelines, and trying to fight that is a bit like trying to eat soup with a fork (ie, pretty silly). There’s a lot more to this topic than can be covered in a single post, so consider this a beginner’s manual on the brain that I hope will encourage you to explore further. The three main sections are all interconnected so it may help to read this a couple of times to get the big picture, but any one of these tips will improve your ability to work efficiently and effectively. Enjoy!

Two Modes – Focused and Diffuse

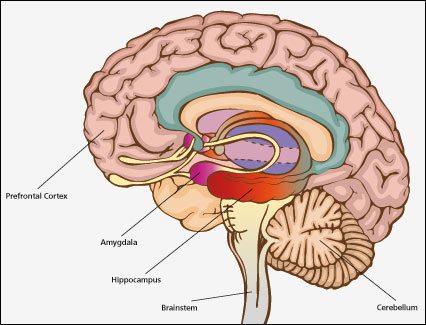

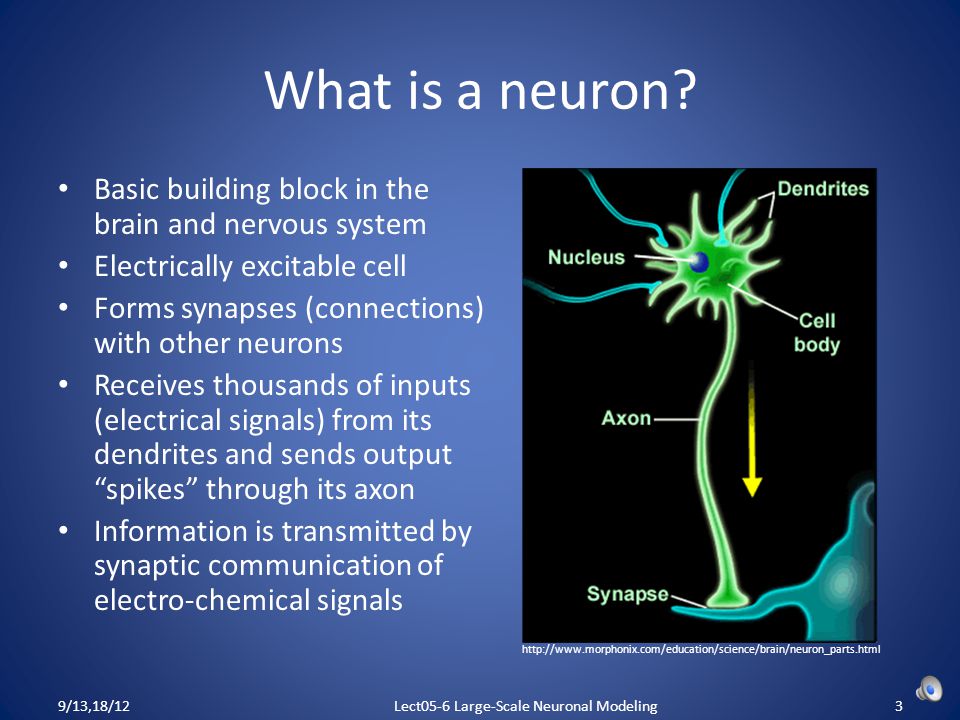

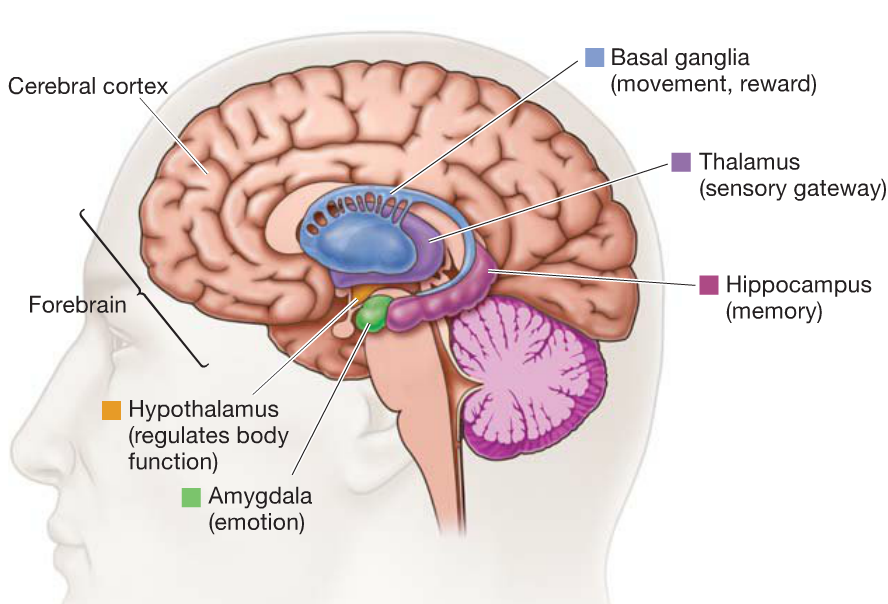

Most of the things that make us human, like conscious decision-making, personality or understanding complex ideas like maths or politics, come from a relatively new part of the brain at the very front behind your forehead, called the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex allows us to focus on a problem, figure out what’s being asked and how to solve it. When we focus on something, over time, the hippocampus starts to knit together a pattern of neurons in our long term memory that fire together more easily the more you revisit those patterns of thinking. I’ll be referring to this process with the expressions ‘neural structure’, ‘neural building’ and 'memory formation'. Memory comes in the form of little rope bridges between neurons (not literally).

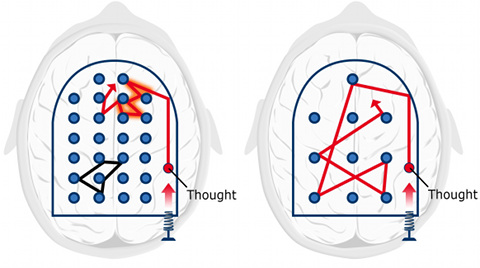

When we focus on a problem, we’re shining a light right up close to certain specific patterns, but sometimes that isn’t enough, and we stay stuck. Thankfully, the brain has a way of dealing with that – the diffuse mode. This mode is activated whenever we bring ourselves out of focusing on a problem, and allows us to shine our torch a little further away from the brain – less brightly, but over a further area. When we’re not focusing, we’re allowing our brain to take a casual stroll through all of the neural patterns it’s built up over time, and suddenly, ‘Eureka!’, inspiration often strikes. It’s why you’re sometimes able to find your keys when you stop thinking so hard about where you left your keys.

To achieve true focus, you need to get rid of all distractions – no phone or internet, quiet location, master a cool dispassion in order to tune out unnecessary/ discouraging thoughts, sleep properly (1 hour rested is more effective for being productive and storing new memories than 3 hours tired), keep regular study times in order to train your brain to be productive at certain times and maintain motivational intensity as best you can. You can do this by finding ways to make the work fun and engaging, and it helps if the subject is one you want to study. Low motivational intensity leads to distraction as the brain searches for higher priorities, while high motivational intensity, once a priority is found, leads to focus.

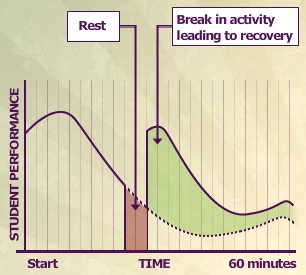

Taking breaks is important as well. As illustrated by this graph, studies have shown that focus dips dramatically over time, but it can be recharged after 5 minutes of unfocused rest. There are specially made Pomodoro apps that can help you keep a good pattern going. For 25 minutes, do nothing but the work, then for 5, focus on nothing in particular. In fact, the latter is a great opportunity to enter the diffuse mode.

Some simple/ easy ways to activate the diffuse mode include physical activity (even taking a walk is a great way to get the mind going, and can even increase production of new neurons in the brain, especially memory neurons), drawing/ painting/ playing music (ideally something already familiar to you so you’re not having to focus too much), taking a bath/ shower, or meditation.

Other things like reading a book or playing a game can activate the diffuse mode as well, but only in the short term before your focus simply switches to the new task and you’re not giving your brain the rest it needs. A little work every day is better than a lot all at once for building neural structure. Think of it like building a brick wall - glue a little bit together with mortar at a time, wait for the mortar to dry, then carry on with the next layer.

It’s a good idea to shift into the diffuse mode when stressed/ angry/ frustrated, as these tend to weaken focus and memory formation. You’ll notice that most diffuse activators, on the other hand, are very calming.

You'll also want to take advantage of sleep – the ultimate diffuse mode. A couple of tricks to try:

Go over/ write down the details of a problem before you go to bed, then try the problem again as soon as possible after waking up.

Go for a power nap – ideally no more than twenty minutes. It’ll give you an energy boost and can offer a more powerful diffuse effect than the same amount of time going for a walk (I'm yet to master this one myself, so let me know how you get on).

Sleep is important because it actually releases toxins that build up in the brain while awake (it’s why you have such a hard time focusing without it – if your brain’s a power plant, without sleep, it’s full of nuclear waste), and also solidifies memories, neural connections, in the brain.

Even when you’re not focusing generally, whether it be chilling after work or hanging out with friends or going for a run, your brain’s still learning and problem-solving, provided your focused mode has put the information in in the first place. The brain works best when you tackle focused work like a weightlifter – work, then rest to make sure your muscles heal and get stronger. This is how we engage strong neural building.

A few more tips and tricks for using these two modes:

Copy and carry technique – write down a problem and all the relevant information you know at the start. Then, carry it around while you do general diffuse things. After a while, come back and see if you fare any better with it.

Pre-reading – before slogging through a chapter in a textbook, skim through it, paying attention to key points as summarised in the back of the chapter and consider, ‘what is this chapter trying to tell me? What are the key questions it’s asking? What are the core ideas?’ – then, as you read, your diffuse mode will have begun work on those questions in the background. With a bit of practice (as with all these techniques), your reading experience should be a lot easier.

Hard-start-jump-to-easy technique – While doing a problem set (I’m a mathematician so I’m using mathy terminology, but these techniques can be used across different subjects) or a test/ exam, start with a hard problem near the back. Focus on it for a couple of minutes until you get stuck or feel you may not be on the right track, then jump away to an easy problem. This gives the brain just enough time to load the problem and work away at it in the background while you focus on something new. When you’ve done as much as you can of the easy problem, jump to a new hard problem, and so on. Trust me, it sounds wacky, but with a bit of practice, it works (I don’t recommend trying this for the first time in a test - that's on you, guy).

Study groups – working as a team to solve problems (provided you don’t get distracted) is like having a bigger brain to work with. Just like the focused and diffuse modes, certain members can be working on different problems from you in the background. Take advantage of that and pool your resources (though bear in mind that you won’t have that giant multi-brain in the exam – everything the group learns, make sure each member learns).

Habits and Organisation

‘All our life’, William James once said, ‘so far as it has definite form, is but a mass of habits’.

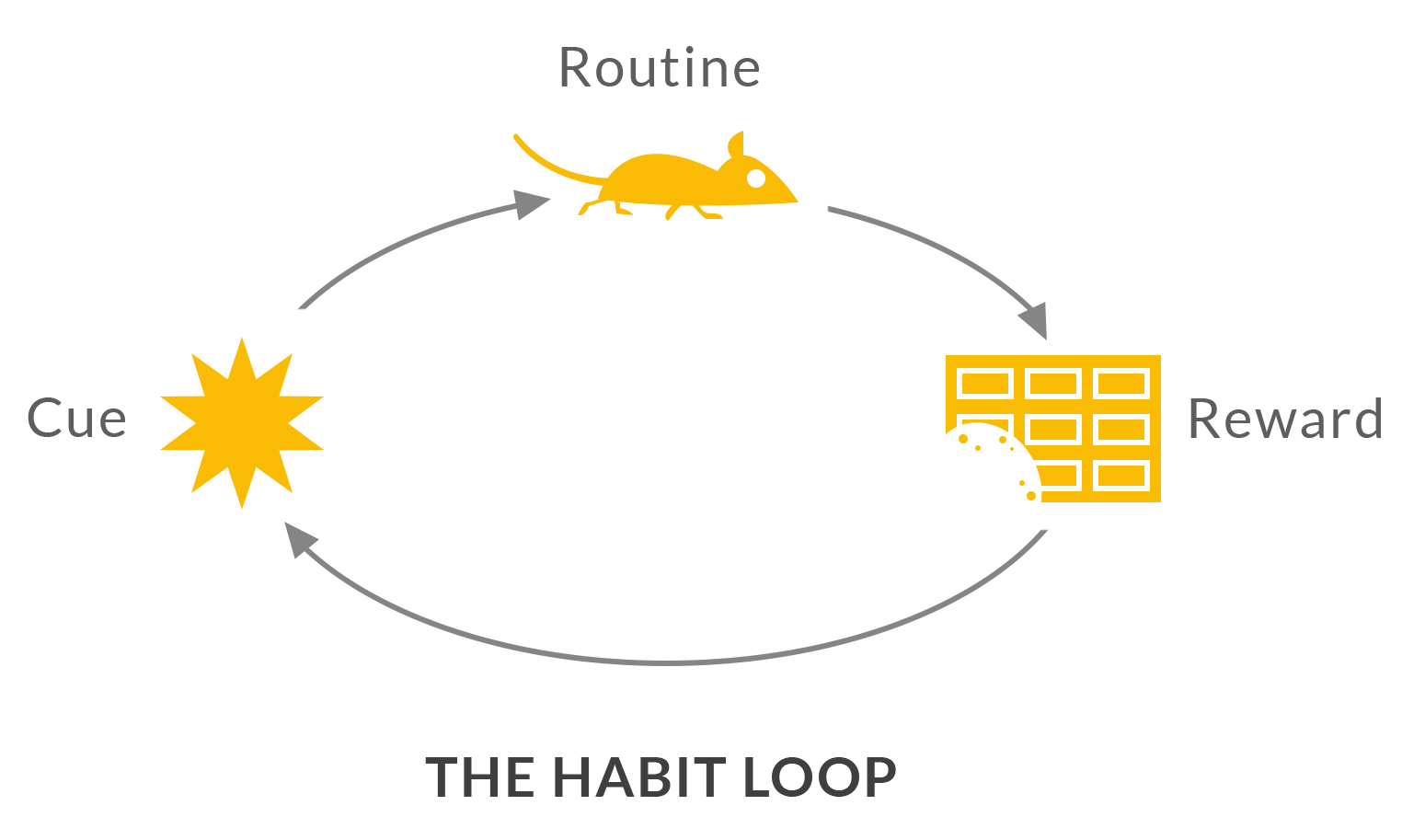

The brain’s a very complex and very expensive piece of kit. Not expensive in terms of money, but in terms of energy (it uses about 20% of the body’s total input). To try and save some of this energy, it turns patterns of behaviour into habits. From then on, when the basal ganglia (not, in fact, latin for 'tall man sprinkled with herbs') gets the right signal, it goes into overdrive and the rest of the brain can take it easy. This happens all the time. You probably don’t remember exactly how you got out of bed this morning. It’s just a habit, right? So how are habits created? It all has to do with The Habit Loop.

When we do anything, it generally begins with a cue (a signal that we want/ need/ are about to begin something), a routine (an activity engaged in as a response to the cue) and a reward (whatever it is that we wanted/ needed). If it’s something we do often, eventually we develop a craving for the feeling of happiness we get from the reward. That craving seals the habit loop and now the more we engage in that pattern, the more we’re on autopilot, the more engaged we are in the habit and the harder it is to fight the craving.

Companies use this to take advantage of you all the time. McDonald's make all their restaurants as identical as possible to trigger cues. People bought toothpaste because they wanted whiter teeth, but it became a ritual because of the craving created by artificially foaming/ adding mint flavour to the paste, which created more sensory stimulation for the brain and therefore greater pleasure in the reward. Dopamine, a pleasure transmitter, is the save button of habits (though no need to go overboard - I don't recommend eating a tub of ice cream to get a jogging habit going).

So from that, we have a few rules:

Creating a new habit:

- Find a simple and obvious cue (like going to your desk or putting your trainers on as soon as you wake up).

- Clearly define the rewards (like satisfaction from a job well done, a sense of belonging/ community, or even just a tasty snack).

- Engage in the routine that you want to become a habit in between (like studying or going for a run)

- Produce a craving through sensory stimulation to close the loop (important and distinct from the reward – some goals produce satisfaction in the short term, but some goals are long-term and studies have shown that the brain is terrible at long-term planning because it sees the future self as a stranger, so to help it along, make sure that even after a day of studying, you’re doing something to make your brain light up (like having a mars bar or a smoothie) after a day of working towards something long term).

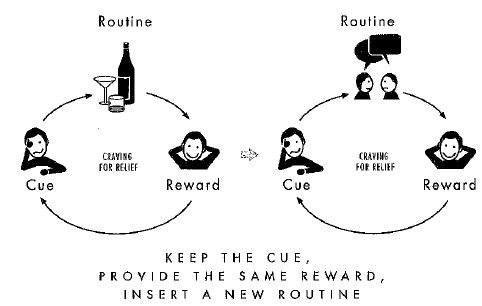

Rewiring a bad habit:

- Same cue (like the sudden need to check your phone)

- Same reward (like the satisfaction and brief escape from existential dread that results from having checked your phone)

- Change the routine - instead of checking your phone, find out exactly what the reward is (in this case probably happiness in general or the need to feel connected) and find something else that will fulfill the reward, like reaching for a book instead, or chatting to a friend in person. Studies of alcoholics show that drinking is merely the routine, and that the true reward is often things like the ability to connect more easily with others or as a means of escape from their problems. To find a new routine to replace the old, consider what you’re really getting emotionally and what the reward actually is.

- Belief – you have to believe that you can change the habit and placing your trust outside of yourself helps – alcoholics who go to AA typically place their faith in God, but trust is the key factor, and studies show that this technique works, so you can also trust in Science.

The basal ganglia is your own private butler that you can train to run errands for you more quickly and efficiently. Work with your butler to create automaticity in areas as diverse as your eating habits or how you react under pressure, to how you solve huge maths problems. As legendary American Football coach Tony Dungy says, ‘champions don’t do extraordinary things. They do ordinary things, but they do them without thinking, too fast for the other team to react. They follow the habits they’ve learned’. How might you apply that to your own discipline?

General organisation tips:

Willpower is a finite resource – schedule the hardest/ least appetising tasks early in the day, batch low intensity/ easy tasks together but avoid multitasking, which is a huge energy drain.

Procrastination and memory are natural enemies – to build neural strong neural structures you have to keep coming back to the information at regular intervals. Start early and avoid cramming.

Fight the Zombies of Attention – the basal ganglia wants you to be a zombie to save energy. Planning things in advance is a bit like having an external basal ganglia – you can spend less energy on deciding between tasks because they’ve already been planned in the past. Plan your week in advance and edit your plan daily. Break tasks down into simple steps. As soon as you reach a part of your plan that isn’t specific or clear, your brain will stall and that gives the zombies a chance to strike.

Burnt ships/ clear-to-neutral technique – remove all distractions. No unnecessary tabs/ programs open/ books on your desk. Make sure your environment is clear of all options that aren’t the task you want to complete. That gives the brain an easy choice and a path through the horde of zombies.

Active Learning and Memory

Active learning is all about building stronger neural structures (ie, memories). Here are a few tips:

Remember that it’s all about practice. Neurons that fire together, wire together.

Spaced Repetition – Space your learning out into regular intervals. Remember the weightlifting analogy – work, then heal for stronger brain muscle. A common pattern to schedule in is to recall the information you’ve learned the next day, then a few days after that, then a week after that, then a couple of weeks after that, then a month and so on. Actively trying to recall the information over longer periods is a great mental workout. Try it with something simple first to get the hang of it. Experiment with a rubix cube or the periodic table. Spaced repetition works great with flash cards.

Chunking – Your working memory only has a handful of slots for information to actively focus on. When you create associations and add pieces of information together in the long term memory through practice, they become chunked. Eventually, whole fields might become chunked and you can work with them simultaneously in the focused mode, each taking up a single slot, which leads to innovation across fields (In Jim Al-Khalili’s case, a slot for Physics and a slot for Biology). Habit-forming is another form of chunking, where a series of actions chunks into a routine.

Interleaving – mix up your learning. Switch subjects over the week and types of problem over a day to not only strengthen but also broaden neural connections.

http://cdn.playbuzz.com/cdn/169cfeea-7fea-4a55-af38-19360fc0e365/7da08d22-1fe0-41a8-8abc-01fe502de2f3.gif

Memory palace (method of loci) – Yes, Sherlock fans, this is a real thing, and it’s a black belt memory technique. Humans have an incredible visual memory. For most of our evolutionary history, we didn’t need to remember a lot of abstract facts and numbers, but we did need to remember all the good spots for berries and how to find our way home after a three-day hunt. Take advantage of that by storing information in your memory of a familiar location, like your house or university campus. Picture the place, then if you want to remember a shopping list for example, start replacing the couch with a loaf of bread and the fridge with a giant milk bottle. Don't be afraid to get a little silly - it helps. It can take up to 15 full minutes of concentration and visualisation to really get this down at first, but with practice it’ll come to you in a few seconds and you’ll be able to remember dozens of items with ease. The nature of most of these memory techniques is that they’re a fantastic way to exercise your brain’s creative skills as well.

Analogy; Association; Explanation – create funny and weird associations that’ll stick in your head. F=ma could become a drawing of a Mule, Flying into some Asparagus. The weirder/ funnier it is, the better your brain will remember. Use your other senses to code the memory all over the brain – feel the wind of the mule flying past you; SMELL the mule! Pretend you’re an electron and fly around the room depending on what the voltage might be. Embrace your inner weirdness and it’ll also make the experience more fun and increase your motivation. Explaining an idea to someone else is also a really powerful way to learn something better. By making this blog post, I’m teaching, so I’m also learning.

Recall > Recognition – Avoid illusions of competence like simply rereading passages and assuming it’s going in the brain. To transfer information to the long-term memory, use it! Put the textbook away after reading a passage and see how much you can remember. By bringing it out of yourself you’re strengthening the memory.

Writing is better than typing and textbooks/ paper is better for learning than staring at a screen. Do as much as work as you can in analog.

Avoid overlearning – getting information down is great, but you want the memories and connections to remain flexible enough that you can be creative with those ideas. Einstellung, or ‘mind set’, can occur when you cram, or in people with higher working memory capacity. You can avoid that by interleaving your work and leaving something for a while if it gets too easy.

Bad habits – passive rereading, over-highlighting (only highlight one sentence/ phrase per paragraph tops, and only when you’ve taken the time to understand it), merely glancing at a problem and assuming you know how to solve it, waiting til the last minute to study, repeatedly solving the same types of problem even after they’ve become easy, neglecting to read the textbook before you start solving problems, not clearing up confusion with teachers/ lecturers and thinking you can learn clearly while constantly distracted all lead to weak neural building. Avoid them as much as possible.

With this and Part 1, I hope I’ve given enough tips and tricks to leave you feeling inspired and ready for the new academic year. If you’d like to see a part 3 in future, feel free to comment either here or on part 1 with suggestions for what you’d like to see. I might even make it in the form of an FAQ-style post. For now, I’m looking forward to getting stuck into some mathematics (which believe it or not is actually the main theme of this blog). Next time I’ll be sharing a few ways in which we can use geometry to unlock the secrets of the world around us, and even the universe. Stay tuned!

- Gerry

(For more science chat, check out my personal blog, which will be beginning proper next month with an interview with Steve Owens, Dark Sky Consultant and Head of the Planetarium at Glasgow Science Centre - coffeeandquasars.wordpress.com)