The Patreon poll for the next series topic is still open. It’s free to vote!

On February 8, 1876, a German engineer named Carl Woldemar Becker and his wife Matilda welcomed the birth of their third child, a daughter named Paula.

Carl was a middle class professional, Mathilda was minorly aristocratic, but their circumstances were less prosperous than that might imply because Carl’s brother had once tried to assassinate the king, which is not the kind of connection that helps you win friends and influence people. Or maybe it does, but only a certain type of people. The result was that they had a home that valued culture and learning, but also the idea that a girl should have a marketable skill because she was going to need it.

At age 16, Paula was sent to England to live with an aunt, study English, and learn to manage a household. She wrote letters home, which included details like “I have just finished making twelve whole pounds of butter, all by myself, and of course I am terribly proud” (Modersohn-Becker 19, letter on July 29, 1892) and, later on, “I sometimes seem so old to myself” (Modersohn-Becker 21, letter on August 19, 1892). Yes, she was still 16.

Butter making aside, the housekeeping lessons were not particularly successful. Her uncle kept the peace between aunt and niece by enrolling her in an art school for hours of every day. Not what her father had in mind when he sent her, but she was happy. When she went back home to Bremen, she enrolled in a two-year teaching seminary because obviously household manager was not the career for her. Paula did this dutifully, but when it was over, did she get a job as a teacher? No, she did not.

She had inherited a bit of money from an uncle. It was not a never-have-to-work-again kind of inheritance. It was just a let’s-postpone-real-life-while-I-find-myself kind of inheritance. She planned two months at a Berlin art school, which she managed to maneuver into two years with the connivance of a few sympathetic relatives, like her mother (Radycki, 54).

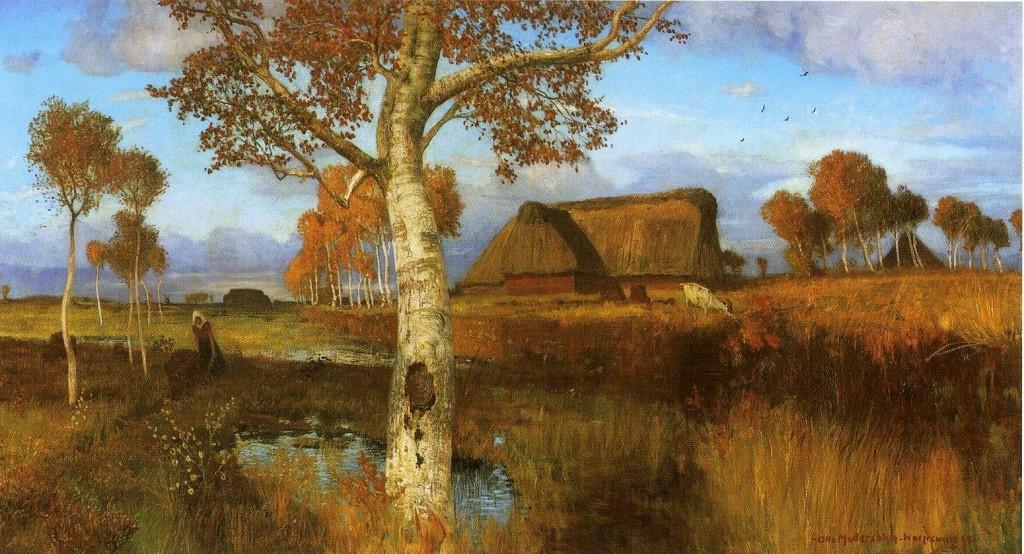

The Worpswede Art Colony

Between school terms she went home to Bremen, or eventually to Worpswede, which was an art colony just outside of Bremen. In Worpswede she met all the people who would matter most in her life: the sculptor Clara Westhoff, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, and the painter Otto Modersohn.

Actually, she saw Otto’s paintings before she saw him. Like most of Worpswede’s painters, he did landscapes and Paula thought they were beautiful.

And then she met him and was still more interested. He was eleven years older than her (which was really no obstacle) and also married (which definitely was an obstacle).

In 1899, Paula still hadn’t gotten around to that teaching job, but she did exhibit in a Bremen art show. You can imagine her, a little shy, a little nervous, trying to be modest, but secretly hoping that someone will discover her as the next artistic genius.

If so, her soul was ripe for crushing. One review said it was “regrettable” that she had been included because the “vocabulary of pure speech [was] not adequate to discuss the work. . . and we are reluctant to make use of impure speech” (Modersohn-Becker 141). And later on, “Why . . . is such a wretched lack of talent . . . permitted to spread itself over wall after wall” in our museum?” (Modersohn-Becker 142).

Paula was not proclaimed an artistic genius. With her delusions of grandeur ground to dust, now she will get that job, right? No, no she won’t. Instead she goes to Paris for more art lessons.

In Paris for the First Time

In Paris the female models were really nude, and the male models were mostly nude, wearing just some whitey tighties. Also cadavers, art students get to work with them too. The world had changed, in that female students were now allowed into such classes, that’s no problem anymore. But yes, the female students were charged twice as much as the male students because why? Because the administration can, that’s why (Darrieussecq, 22).

(Wikimedia Commons)

Paula was delighted to win a prize at the Academy. She was also delighted to see the art studios and galleries, so many artists doing so many interesting things. For that matter, so many people doing so many interesting things. Paris was a bit of an eye opener for the middle-class German girl. She wrote home about the Parisian behavior and added that “after such self-indulgence, we Germans would perish from moralistic hangovers” (Darrieussecq, 26).

Having found her artistic paradise, Paula was eager to share it. She wrote Otto Modersohn and his wife, Hélène (but really just Otto), that they should come experience Paris too. They wrote back that Hélène was sick. Without missing a beat for propriety or tact, Paula wrote ok, well, Otto should come alone then.

He said no. Then he said yes. Then he came. Then Hélène died while he was away. Oops.

Marriage and Family

Otto rushed home and Paula followed him there. Four months later they were engaged. To be fair, there were practical reasons for the hurry. Paula wanted her father to stop badgering her about trivial concerns like a steady paycheck. Otto had a small daughter and conventional wisdom said she needed a mother. There is also no doubt the two were very much in love with each other and each other’s art.

Paula’s parents were not so thrilled, though, to be honest, I am not sure why not. Otto was a rare breed: an artist who actually made a comfortable living. But for the time being, all they said was you can’t get married until you learn to cook. So it was off to an aunt for two months of cooking lessons. Two whole months of no time to paint!

They married in 1901 and honeymooned in Dachau (Dass, 64). These days if you visit Dachau, you are visiting a concentration camp, but the 20th century was still very young and comparatively innocent, and Dachau was another art colony. Then they returned to their own art colony, and reality began to settle.

On the surface, all was well. Paula moved into a comfortable home with servants. The servant also took care of Otto’s little girl. Paula painted full time: every day from 9 to 1 and again from 3 to 7, but without the pressure to sell the art because Otto was taking care of that (Radnycki, 90). As a wife, her career was not really taken seriously, and it’s interesting that that sort of cut both ways. No money, little encouragement, but also no soul-crushing pressure and economic reality forcing her into a job she didn’t want and would prevent her from painting.

Though she had achieved what many a woman considered success, Paula was dissatisfied. She was dissatisfied with her friend Clara, who now felt remote and unfriendly. Clara had married the poet Rilke. She had a new baby and financial difficulties to cope with, and Paula could not understand why that had changed their relationship.

She was also dissatisfied with Otto. Less than a year into marriage, she wrote in her journal:

“My experience tells me that marriage does not make one happier. It takes away the illusion that had sustained a deep belief in the possibility of a kindred soul. In marriage one feels doubly misunderstood. For one’s whole life up to one’s marriage has been devoted to finding another understanding being. And is it perhaps not better without this illusion, better to be eye to eye with one great and lonely truth?

I am writing this in my housekeeping book on Easter Sunday, 1902, sitting in my kitchen, cooking a roast of veal.”

Journal entry on March 30, 1902 (translated in Paula Modersohn-Becker, the Letters and Journals, 274-275)

What exactly the problem was is not clear. There are later hints that Otto struggled with sexual dysfunction, and one of my sources goes so far as to say this marriage was completely unconsummated. (Radycki). I think that’s quite a stretch, personally, given that Otto already had one child, and would go on to have three more. The one contemporary letter that says it was completely unconsummated is not from either of them, but from Clara, so her information was second hand. But whatever the trouble, Paula was no longer a radiant bride, and neither was she a radiant mother.

I Am a Painter

She was also dissatisfied with her art. Having seen Paris, the comfortable landscapes done in Worpswede now seemed a little insipid, a little predictable, a little so-last-century. In her own work she began to abandon perspective. She also abandoned landscapes, focusing instead on still life and figures, especially nude figures. Here at least she could feel that great things were going to happen, even if they had not yet happened. She wrote to her mother, “The dawn has broken in me and I can feel the day approaching. I am going to become somebody. . . I feel that the time is soon coming when I no longer have to be ashamed and remain silent, but when I feel with pride that I am a painter” (Modersohn-Becker 282, letter on July 6, 1902). One senses that that review from 1899 may still have hung heavy on her.

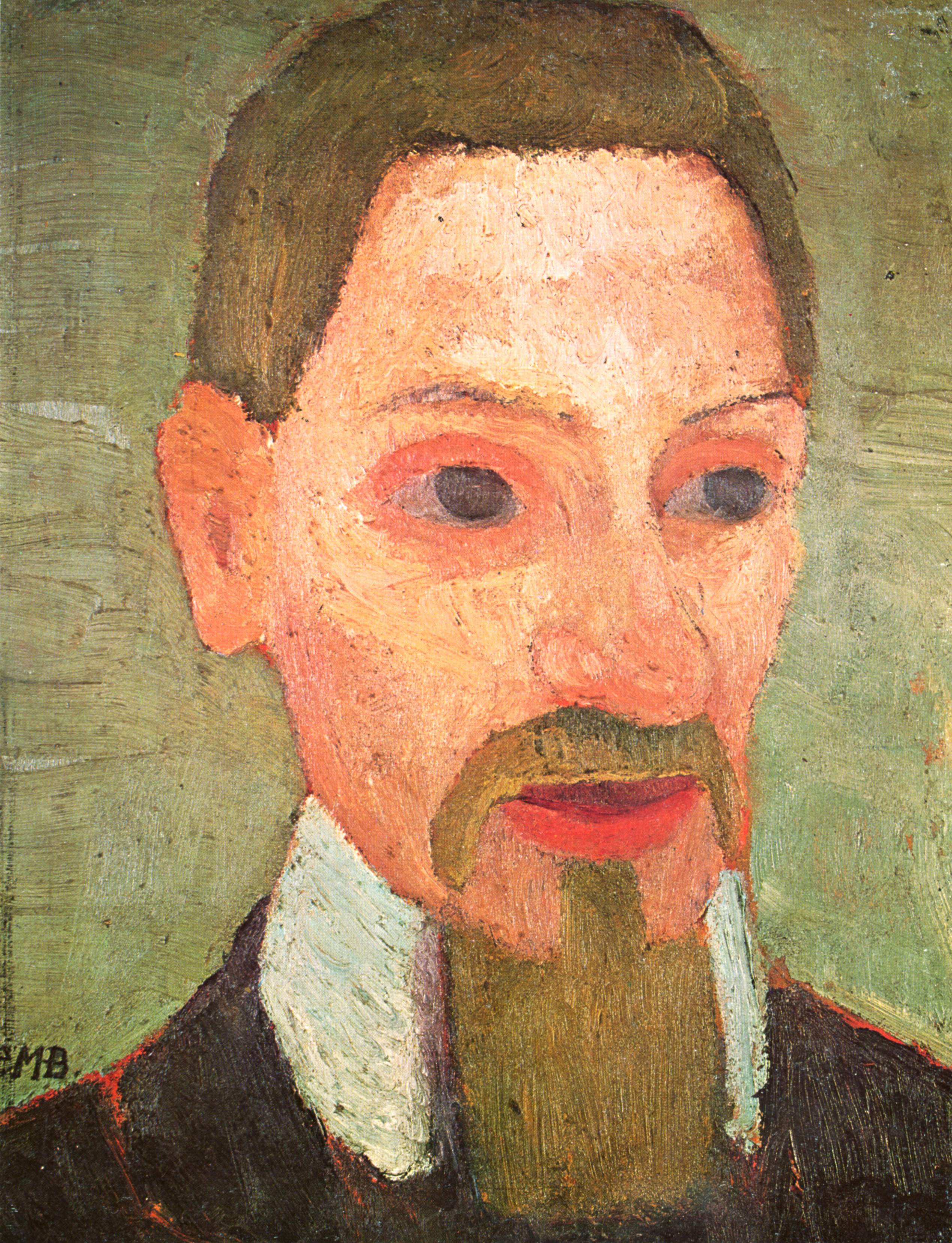

In 1903, Paula returned to Paris and stayed for five weeks. Otto did not come, though she thought he should. She was just as delighted and moved as the first time. She even met Rodin, by way of an introduction letter from Rilke in which he described her not as a painter, but as the wife of a distinguished painter (Modersohn-Becker 303, letter on March 2, 1903). Ho hum.

She went home still more changed. She painted still lifes of the meals she wanted to eat: fried eggs and fruit (not nearly enough to keep Otto alive, she wrote). Her still lifes are nothing like the carefully arranged, glistening bounty that you might be imagining. No, hers look distinctly feminine, by which I think the art historians mean that they are in the feminine space of a house: in the kitchen, not the dining room, and they are presented not as a finished product, but mid-stream in a woman’s list of tasks: silverware that isn’t fully set, oranges that aren’t fully unpacked from the carton, a tablecloth not straightened out (Radnycki, 107).

She was also looking for inspiration outside the house. She painted children, not to look cherubic, but sometimes at their most unattractive: thin and drooping and nude. She went to the poor house and painted the people there, not as any political statement but just as she saw them. (Radnycki, 114), ugliness and all. All traditional goals of realism and perspective and conventional beauty were gone now.

Otto was baffled. He had once been a great champion of hers. Only a year earlier he had written, “she is a genuine artist such as few in the world are… No one knows her, no one appreciates her—someday that will change (Modersohn-Becker 280, from Otto’s journal June 15, 1902).

But now he wrote “Paula hates to be conventional and is now falling prey to the error of preferring to make everything angular, ugly, bizarre, wooden. Her colors are wonderful, but the form? The expression! Hands like spoons, noses like cobs, mouths like wounds, faces like cretins. She overloads things… It is difficult to give her advice, as usual” (Modersohn-Becker 324 from Otto’s journal September 26,1903).

Art historian Diane Radnycki explains in her book that Otto’s criticisms are thin and facile and no doubt they are, but I mention it because I think there are many people who would totally agree with Otto, at least on some of Paula’s paintings. Art had by this point moved on from a purely realistic depiction (if it had ever really been purely realistic). The camera had been invented, so there was no need for artists to do that. It was now about portraying the viewpoint and craft and perspective of the artist, more than it was about a one-to-one match with reality.

1904 and 1905 would pass with several restless moves, some with Otto, some without. Paula was in Paris alone when Otto’s mother died. She wrote him bemoaning that she was not there to hold his hand in the grief, and how difficult the days must be for him, and asking whether she ought to come home because she totally will to support him, only she’s greatly interested in the things in Paris, and really maybe he could just come see her, he would find the modern artists so extremely stimulating and here’s a list of the ones she still plans to visit while she stays in Paris (Modersohn-Becker 357, letter on March 10, 1905)

It is without a doubt, the most emotionally insensitive condolence letter I have ever read. And yet the other letters are still full of expressions of love and reading them you would not guess that the breaking point was near.

Painting Real Women

On February 24, 1906, Paula wrote in her journal: “I have left Otto Modersohn and am standing between my old life and my new life. I wonder what the new one will be like. And I wonder what will become of me in my new life? Now whatever must be, will be” (Modersohn-Becker 384).

She went to Paris, of course. It was where she felt most hopeful. Otto was devastated. At home in Worpswede, he took her paintings into his own studio and copied them, trying desperately to understand her (Radnycki, 100). He wrote her long letters trying to convince her to come back. She sent him very firm letters in response. But she also asked for money. She painted full time, but she did not have a career or a reputation or a paycheck.

In her Paris art studio, she was painting what would become her most famous work, and the subject is highly suggestive. Almost twenty self-portraits. Self-portraits are fairly common in art history, but they had almost never been nude and lifesize before. They had never been nude and lifesize and female and pregnant before (Radnycki, 148).

The most famous of these shows her with tilted head, an amber necklace and her hands protectively cradling her protruding belly. She signed it by writing “I painted this at age 30 on my 6th wedding day/P. B.” (Radnycki, 148).

The trouble is that Paula was not pregnant in May of 1906. Some historians have tried to say that a round belly was in some cultures a sign of beauty. If so, it’s a sign of beauty that I wholeheartedly endorse. The trouble is I don’t live in such a culture and neither did Paula. Corsets were in. The rounded belly definitely meant pregnancy. And yet just a month earlier she had written Otto harshly that she didn’t want any child from him, not now, not anymore (Modersohn-Becker 389, letter April 9, 1906). But motherhood was certainly on her mind.

The second most famous painting she did is also from this time.

It’s a reclining female nude, which was nothing new. Except that this one is because the woman was not signaling sexual availability. She is an exhausted mother, with her naked baby nursing at one breast. This is a woman who looks like a woman, complete with pubic hair, a loose belly, and large, functional areolas. Both of this and the previous self-portrait have been described as “weird” and “I don’t get why anyone would do that” and “maybe being pregnant made her act strange.” The art professor who recorded these student reactions said they were all from male students (Quinn, 94), and maybe so. But I’m pretty sure I know a lot of women who would also find it weird.

A lot of my sources wax lyrical on the question of why anyone would do that, and to answer I think you have to go back to see why artists paint nudes at all. They had stemmed from the Renaissance, when the idea was that the humanity, both body and intellect, was the pinnacle of God’s creation and worthy of celebration. Since that time, the serious artists, the real artists had depicted that body, male and female. But it was usually depicted at that pinnacle point in a human being’s life: young, strong, beautiful, sculpted. Bulging muscles for the men, sumptuous curves for the women.

This is particularly problematic on the subject of the women because the vast majority of the artists were men. Even when Artemisia Gentileschi painted nude women, the vast majority of her patrons were men. So there was always the question of the male perspective: what they wanted a woman to look like and what they wanted a woman to be.

It’s the total absence of that that makes Paula’s work startling. To quote biographer Marie Darrieussecq:

“In Paula’s work there are real women. I want to say women who are naked at long last: stripped of the masculine gaze. Women who are not posing in front of a man, who are not seen through the lens of men’s desire, frustration, possessiveness, domination, aggravation. Women in the work of Modersohn-Becker are neither coquettish (Gervex), nor exotic (Gaughin), nor provocative (Manet), nor victims (Degas), nor distraught (Toulouse-Lautrec), nor fat (Renoir), nor colossal (Picasso), nor sculptural (Puvis de Chavannes), nor ethereal (Carolus-Duran). Nor made of ‘pink and white almond paste’ (Cabanel, whom Zola made fun of). With Paula there is no getting even at all. No sign of rhetoric, or judgment. She shows what she sees.”

Marie Darrieussecq (Being Here Is Everything, p. 122)

The only caveat I will add there is that, like all of us, what Paula saw was in some ways molded by what she wanted to see. She wanted to be a creative force, definitely through painting, and maybe also through motherhood. The power to create is what she saw.

Reconciliation

A week after Paula finished her self-portrait, Otto surprised her by showing up. Rilke was there with her as she was painting his portrait. Finding her alone with a man was probably not helpful. Finding a nude, pregnant-looking self-portrait on the wall signed with her maiden initials only can’t have helped either. The scene was not pleasant. Paula did not go home. But she did continue writing to Otto that hot summer.

And in September, she wrote a change of heart. An apology. As she put it, a sudden shift in the way she felt (Modersohn-Becker 409, letter on September 9, 1906). In November, a letter to Clara saying:

I shall be returning to my former life but with a few differences. I, too, am different now, somewhat more independent, no longer so full of illusions. This past summer I realized that I am not the sort of woman to stand alone in life. Apart from the eternal worries about money, it is precisely the freedom I have had which was able to lure me away from myself. I would so much like to get to the point where I can create something that is me.

It is up to the future to determine for us whether I’m acting bravely or not. The main thing now is peace and quiet for my work, and I have that most of all when I am at Otto Modersohn’s side.

I thank you for your friendly help. My birthday wish for you is that the two of us will become fine women. . . .

Your Paula Modersohn

Letter on November 17, 1906 (translated in Paula Modersohn-Becker, the Letters and Journals, p. 413)

What brought about this change is unclear. Ideas vary from the cynically financial to the idealistically romantic. My own thought is that people are complicated, and they rarely have only one motive for what they do.

Whatever the reason, she went back to Worpswede, continued painting, and she was soon expecting a baby. She did paint herself pregnant, so even if you don’t count that famous one from the year before, she is still the first artist to do that.

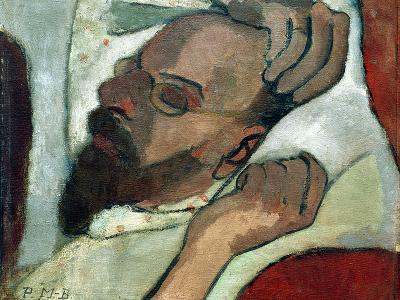

On November 2, 1907, baby Mathilde was born. It was a difficult birth, but both mother and child survived. Paula was advised to stay in bed to recover. After eighteen days, she was allowed to get up. At which point she immediately collapsed and fell to the floor. Her only word was “Schade”, which means “a pity” and she was dead. She was 31 years old.

Pulmonary embolisms are still a leading cause of maternal death. They occur because a blood clot forms in the mother’s legs. If it gets big enough, then when she does stand up, the clot blocks the lungs, causing a quick death. The solution does not have to be any modern high-tech miracle. It is likely that if Paula had simply gotten out of bed earlier and walked around, as most modern mothers are told to do, she probably would have lived.

Legacy

During her brief lifetime, Paula was not even an emerging artist. She was a complete unknown. She had sold a grand total of three paintings, mostly to friends who were trying to be supportive. She had rarely exhibited. Only one of those exhibitions had received even one positive review. Even her neighboring artists in Worpswede had not seen most of her work. She had never shown it to them.

But her immortality was not long in coming. Her mother collected and edited her letters and published them. They became an unlikely bestseller, which I think just goes to show that this was still a world without Netflix binging. People had time to sit around and read collections of letters. Tens of thousands of Germans who had never seen her art (and wouldn’t have liked it if they had) knew her as a charming writer. And she is charming. Art exhibitions began to take note and show her work.

Ludwig Roselius, a man who got rich by inventing decaffeinated coffee, decided to spend his riches on a museum. The Paula Becker Modersohn museum opened in 1927. It was the very first museum devoted entirely to a female artist (Radnycki, 149). Roselius managed to keep the museum open even after the Nazi party declared her a degenerate artist, confiscating and destroying some of her work. Among other criticisms, the Nazis found her lacking in “sensitive maternal quality” (Perry, 63). Just think about that for a moment.

Since the war, Paula’s fame, influence, and critical acclaim has only grown. She is truly a painter, just as she said she said would be, just as Otto predicted she would be. Art historians write many things about her use of color, about her breaking open of the nude genre, about the amazing synchronicity of her work and Picasso’s, who was still only just beginning to transform art.

In the end, I feel like Paula’s story ends with a lot of what ifs. What if she’d had equal access to education and exhibitions? What if that first review of her work had been positive and she’d felt encouraged to share her art more? What if she had lived in a world where her career was taken as seriously as her husband’s? What if her doctors had told her to get out of the postpartum bed earlier? What if she had painted for another four or five decades? What might she have created, if she had lived?

Selected Sources

Cornell University. “What Every Woman Should Know about Pregnancy and Pulmonary Embolisms | Patient Care.” Weillcornell.org, weillcornell.org/news/what-every-woman-should-know-about-pregnancy-and-pulmonary-embolisms#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20most%20severe.

Darrieussecq, Marie. Being Here Is Everything : The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker. South Pasadena, Ca, Semiotext(E), Cambridge, Mass, 2017.

Modersohn-Becker, Paula. Paula Modersohn-Becker, the Letters and Journals. Northwestern University Press, 1998.

Perry, Gillian. Paula Modersohn-Becker. Harper & Row, 1979.

Quinn, Bridget. Broad Strokes. Chronicle Books, 7 Mar. 2017.

Radycki, Diane. Paula Modersohn-Becker : The First Modern Woman Artist. New Haven, Yale Univ. Press, 2013.

[…] week I talked about Paula Modersohn-Becker, the early expressionist painter. One of her deepest friendships was with Rainer Maria Rilke, the […]

LikeLike

[…] paintings were shocking at the time, and they are still shocking now. Remember two posts ago when Paula Modersohn-Becker was weird for painting herself nude and pregnant? Well, in comparison with Frida, Paula looks […]

LikeLike