Abstract

Background

Overuse of health care resources has been identified as the leading contributor to waste in the US health care system.

Objective

To explore health care system factors associated with regional variation in systemic overuse of health care resources as measured by the Johns Hopkins Overuse Index (JHOI) which aggregates systemic overuse of 20 health care services.

Design

Using Medicare fee-for-service claims data from beneficiaries age 65 or over in 2008, we calculated the JHOI for the 306 hospital referral regions in the United States. We used ordinary least squares regression and multilevel models to estimate the association of JHOI scores and characteristics of regional health care delivery systems listed in the Area Health Resource File and Dartmouth Atlas.

Key Results

Regions with a higher density of primary care physicians had lower JHOI scores, indicating less systemic overuse (P < 0.001). Regional characteristics associated with higher JHOI scores, indicating more systemic overuse, included number per 1000 residents of acute care hospital beds (P = 0.002) and of hospital-based anesthesiologists, pathologists, and radiologists (P = 0.02).

Conclusions

Regional variations in health care resources including the clinician workforce are associated with the intensity of systemic overuse of health care. The role of primary care doctors in reducing health care overuse deserves further attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Health care spending in the United States (US) accounts for roughly 17% of the country’s gross domestic product.1 While US per capita health care spending is more than twice than that of other major industrialized countries, the US health care system fails to achieve health outcomes that are comparable to other developed nations.2,3,4 Additionally, health care spending in the US does not positively correlate with indicators of quality such as patient satisfaction or access.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Recognizing this, diverse stakeholders have prioritized the identification and elimination of health care waste in order to reduce health care costs and improve patient outcomes and overall population health.12,13,14,15

Overuse is the provision of care where the potential for harm exceeds the potential for benefit16,17,18 and has been identified as the most significant contributor to the high cost of health care. Importantly, the overuse of medical services not only has an opportunity cost through the misallocation of resources, but it physically and psychologically harms patients. In the Medicare population, 14–25% of beneficiaries receive at least one low-value service per year.19,20,21 It has been proposed that our health care system should adopt a value-driven strategy to identify and eliminate overuse of services. Recent advances in the measurement of overuse have laid the necessary groundwork for identifying the factors that are associated with this phenomenon.22

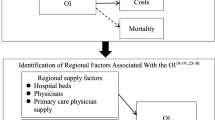

We previously identified 20 clinically diverse claims-based measures of overuse including 13 diagnostic tests, 2 tests for screening, 1 test for monitoring, and 4 therapeutic procedures and aggregated them into an index to measure systemic overuse, which we consider to be a general tendency of an organization or region to overuse medical services (Appendix).20, 23, 24 The clinical areas of overuse considered by the Johns Hopkins Overuse Index (JHOI) include 4 relevant to primary care practice, 3 relevant to otolaryngology, 3 to radiology, 2 to cardiology, and 1 each to neurology, emergency medicine, allergy, oncology, end of life care, urology, physical therapy, and surgery.23 This approach enhances our ability to study the broad determinants that might drive overuse. The index was developed in the Medicare population and was designed to reliably identify overuse using a single year of data.24 In this work, we aimed to examine the association between the supply of regional health care resources and systemic overuse, as measured with the JHOI.

METHODS

Data Sources

We used a 5% sample of fee-for-service patients insured by Medicare in 2008 taking data from the Denominator, MedPAR, Carrier, and Outpatient files. We limited our cohort to beneficiaries that had 12 months of complete enrollment in Medicare Part A and Medicare Part B or death during 2008, were at least 65 years old, and were never enrolled in a Medicare Health Maintenance Organization during that year. We used residential ZIP codes to assign each beneficiary to one of 306 hospital referral regions (HRR) as defined in the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.25

Systemic Overuse Measurement

For each of the 306 HRRs, we calculated the Johns Hopkins Overuse Index (JHOI) which uses 20 clinical services to capture the latent tendency of a region or system to overuse health care resources.24 These 20 services were chosen because they could be operationalized using a single year of claims data and each one is overused with sufficient frequency and variance to contribute valuable information to the index.20, 23 We used a combination of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and current procedural terminology (CPT) codes from 12 months of claims to identify likely overuse events with consideration of patient demographic and clinical characteristics including age, sex, and current diagnoses.

Predictor Variables

HRR-level characteristics included medical market characteristics as well as demographic and population data taken from the Dartmouth Atlas and the 2006 Area Health Resource File (AHRF) from the Health Resources and Services Administration.25, 26 Regional economic well-being was assessed based on the count of Medicaid eligible persons. We measured the supply of regional health resources per 1000 residents, including the number of acute care hospital beds, primary care physicians (i.e., physicians in family practice, general internal medicine, and pediatrics), medical specialists, hospital-based specialists (i.e., anesthesiologists, pathologists, and radiologists), and surgeons. Medical specialists include all physicians who are not primary care physicians, hospital-based specialists, or surgeons.

Statistical Analysis

We used ordinary least squares regression and multilevel models to estimate the association of the HRR-level characteristics with the JHOI (i.e., \( \frac{\Delta \mathrm{overuse}}{\Delta \mathrm{resources}} \)). We clustered the HRRs by the nine census regions. A Hausman test was performed to determine whether a region-level fixed effect or subject-specific random effect (i.e., random intercept) model was more appropriate. We used lagged covariates (i.e., AHRF data from 2006) to avert reverse causation, a situation in which overuse could have induced an increase in the supply of resources. Because the JHOI accounts for population demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, and race) and patient case-mix using Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG), we did not risk-adjust this analysis. We conducted three sensitivity analyses to determine whether our results were robust to alternative specifications; accounting for the economic well-being of a region, excluding extremely overusing areas, and selecting different structural characteristics.

We then explored the extent to which the relationship between the supply of health care resources and systemic overuse is associated with two downstream outcomes: spending and mortality. First, a multilevel model was used to estimate the association between the JHOI and the average medical cost per Medicare beneficiary per year in each HRR and each HRR’s overall 30-day post-discharge mortality rate. Total medical costs for each HRR included reimbursements from Medicare and any primary insurer and patient out-of-pocket payments for all inpatient and outpatient services. We obtained 30-day post-discharge mortality rates for each HRR from the Denominator and MedPAR files. Next, we estimated the effect of the supply of health care resources on health care costs:

and the effect of the supply of health care resources on mortality:

where \( \frac{\Delta \mathrm{overuse}}{\Delta \mathrm{resources}} \) is the coefficient associated with the structural indicators from the previous model.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS and Stata software. The preparation of the JHOI was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability

The SAS code used to generate the Johns Hopkins Overuse Index is available upon request to the authors.

RESULTS

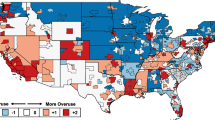

The 2008 Medicare sample included information about 551,028 men and 900,114 women after removal of 8391 individuals with ZIP codes that could not be matched to an HRR. Sample demographics were generally similar to the characteristics of the overall Medicare population (Table 1). On average, each HRR had 2.5 acute care hospital beds, 0.70 primary care physicians, 0.41 medical specialists, 0.24 hospital-based specialists, and 0.41 surgeons per 1000 residents, but this varied greatly between regions (Table 1). For example, the number of hospital beds per 1000 residents ranged from 1.44 in Everett, WA, to 4.71 in Monroe, LA, and the number of primary care physicians per 1000 residents ranged from 0.44 in Odessa, TX, to 1.17 in San Francisco, CA. Given that the index is normalized, across the 306 HRRs, the JHOI had an average of 0.00 and a standard deviation of 1.00 points. The lowest value of the JHOI was − 2.07 in Tuscaloosa, AL, and the highest was 4.35 in Palm Springs/Rancho Mira, CA (Table 1).

The supply of regional health care resources was associated with systemic overuse in the Medicare population (Table 2). The random effects model suggested that each additional acute care hospital bed per 1000 residents in an HRR was correlated with a 0.31-point increase in JHOI (p = 0.002); one additional hospital-based specialist per 1000 residents was correlated with a 5.9-point increase in JHOI (p = 0.022); and one additional primary care physician per 1000 residents was correlated with a 3.8-point decrease in JHOI (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The Ramsey RESET test indicated no misspecification in the functional form of the model (p = 0.511) and a Hausman test supported the use of a random effects model due to improved efficiency (p = 0.997). Accounting for unobserved region-level characteristics in the fixed effect model did not change the correlation between structural indicators and JHOI. These results were robust to sensitivity analyses that accounted for the economic well-being of a region, that excluded extremely overusing areas, and that included alternative structural factors in the model.

Johns Hopkins Overuse Index by number of primary care physicians per 1000 residents within each of 306 Hospital Referral Regions (β = − 3.75, P < .001), using a random effects regression model clustered by census region to control for hospital beds, medical specialists, hospital-based specialists and surgeons per 1000 residents.

We estimated that a one-unit increase in the JHOI was associated with $169 (SE $69) increase in total medical cost per Medicare beneficiary per year. Therefore, we estimate that every additional hospital bed per 1000 residents in an HRR is associated with an increase in annual total medical costs by $52 [95% CI $10, $94] for each Medicare beneficiary in that HRR and that one additional hospital-based specialist in an HRR is associated with increased annual costs by $1000 [95% CI $200, $1801] per beneficiary in an HRR. Conversely, one additional primary care physician per 1000 residents in an HRR is associated with reduced annual total health care spending of approximately $634 [95% CI $127, $1141] per Medicare beneficiary. In terms of health outcomes, because a one-unit increase in the JHOI was associated with 0.57% (SE 0.25%) increase in the overall 30-day post-discharge mortality rate in an HRR, one additional hospital bed per 1000 residents in an HRR may be associated with increased 30-day mortality by 0.18% [95% CI 0.02, 0.33] and one additional hospital-based specialist per 1000 residents in an HRR may increase 30-day mortality by 3.37% [95% CI 0.47, 6.28]. In contrast, every additional primary care physician per 1000 residents was associated with reduced 30-day mortality by 2.14% [95% CI 0.30, 3.98].

DISCUSSION

Our analyses of Medicare data from 2008 support that the structural supply of regional health care resources is associated with systemic overuse. Specifically, the strong association between the supply of acute care hospital beds and hospital-based specialists suggests that these resources may induce systemic overuse while the supply of primary care physicians might have a protective effect. We hypothesize that these associations reflect differences in practice styles and the overarching “culture of overuse” in each region. The density of surgeons did not strongly impact systemic overuse.

While there is mixed evidence to suggest that provider organizations and regions with a higher proportion of primary care physicians have lower spending and better use of certain preventive services, our study advances this literature by focusing specifically on overuse.27, 28 Given the estimate that workforce characteristics explain 42% of the state-level variation in Medicare spending per beneficiary, it is valuable to decompose this spending into more specific components.29 Our analysis also complements a previously published exploratory analysis, which found that a higher HRR-level ratio of specialists to primary care physicians was associated with greater use of 11 low-value services.21 In light of the argument that efforts to reduce health care costs are unlikely to be successful without scaling back health care employment growth, this research suggests that such a policy would need to target certain types of providers more than others.30

Methodologically, this study makes two contributions. First, while prior studies of overuse have tended to focus on a single service or procedure, this study utilized an index to capture the general tendency of an organization or region to overuse medical services. This approach allowed us to study overuse as a system-wide phenomenon and to draw conclusions about regional health services use as a whole. Second, our measure applies algorithms to detect the individuals that actually received a clinical service that was an overuse event. Previous research that relies on variation in rates of utilization may be distorted by widespread underuse or overuse, or by regional differences in patient or clinician practice preferences.15, 31, 32

Given the sensitivity of the JHOI, it can be used to estimate how changes in systemic overuse among the 55 million people enrolled in Medicare might influence total spending. For instance, a one-unit decrease in the JHOI within each HRR could equate to $9.3 billion in Medicare savings. Furthermore, a net savings of $24.2 billion might be achieved by investing $10.7 billion to increase the supply of primary care providers by 1 per 1000 beneficiaries.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we used a 5% sample of Medicare claims to generate the JHOI, and therefore only included measures applicable to the elderly population. While our measurement of systemic overuse focused on the Medicare population, it is important to note that the health care resources that are attributed to a geographic region are based on the entire population. Second, our data is approximately 10–12 years old. In the last decade, Medicare has undergone substantial changes including the growth of Medicare Advantage and the introduction of numerous pay-for-performance and value-based programs.33, 34 However, overuse is an enduring problem that occurs across insurance types and settings—even initiatives such as Accountable Care Organizations have not meaningfully reduced overuse.5, 35,36,37 This suggests that our results are relevant to current health policy conversations. In terms of data, future research should explicitly study the pervasiveness of systemic overuse over time and utilize other sources of claims data to study a younger US population. Third, to combat the issue of reverse causation, we used lagged covariates but future research could improve upon this by using multiple years of data to construct a panel. Fourth, studies may also use smaller units of observation (e.g., county-level) to increase sample size and improve the precision of estimation. It is also worth noting that beneficiaries were assigned to a HRR based on their home ZIP codes, rather than where they may have actually received care.

We recognize that the factors that are associated with systemic overuse may also be associated with some measures of high-value care. Therefore, combining measures of overuse with measures of underuse may be important when evaluating the effect of programs that intend to achieve more cost-effective, high-value care. By including multiple structural indicators in the model and testing them concurrently, we did our best to reduce bias in the estimates that might be due to strong correlations between the indicators.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the supply of regional health care resources are associated with the intensity of systemic overuse. This study also supports increased attention to primary care as a strategy to lower per capita costs and improve health.

References

Hartman M, Martin AB, Espinosa N, Catlin A, The National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National health care spending in 2016: Spending and enrollment growth slow after initial coverage expansions. Health Aff 2018;37(1):150–160.

World Health Organization. Ranking of the world’s health systems. 2013.

Bentley TGK, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB. Waste in the U.S. health care system: A conceptual framework. Milbank Q 2008;86(4):629–659.

Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, Catlin A. National health spending: Faster growth in 2015 as coverage expands and utilization increases. Health Aff 2017;36(1):166–176. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1861775537. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1330.

Colla CH, Morden NE, Sequist TD et al. Payer type and low-value care: Comparing choosing wisely services across commercial and medicare populations. HSR 2017.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA et al. The implications of regional variations in medicare spending. part 1: The content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(4):273–87.

Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES. Regional variations in health care intensity and physician perceptions of quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(9):641–9.

Fowler Jr FJ, Gallagher PM, Anthony DL, Larsen K, Skinner JS. Relationship between regional per captia medicare expenditures and patient perceptions of quality of care. JAMA 2008;299(20):2406–12.

Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA 2000;284(4):483–485. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.4.483.

Anthony DL, Herndon MB, Gallagher PM, Barnato AE, Bynum JP, Gotlieb DJ, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. How much do patients’ preferences contribute to resource use? Health Aff 2009;28(3):864–73.

Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs--lessons from regional variation. NEJM 2009;360(9):849–52.

Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA 2012;307(14):1513–1516. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.362.

Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell EA, Bishop T, Keyhani S. Overuse of health care services in the united states: An understudied problem. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(2):171–178. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.772.

Schpero WL. Limiting low-value care by “choosing wisely”. Virtual Mentor: VM 2014;16(2):131–4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24553334.

Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, et al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. 2017.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Glossary: Underuse, overuse, misuse. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/glossary/u. Updated 2017.

Emanuel EJ FV. The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA 2008;299(23):2789–91.

Institute of Medicine, Robert Saunders, Leigh Stuckhardt, J. Michael McGinnis. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in america. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2013. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2012/Best-Care-at-Lower-Cost-The-Path-to-Continuously-Learning-Health-Care-in-America.aspx.

Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Measuring low-value care in Medicare. JAMA Int Med 2014;174(7):1067–1076. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1541.

Segal JB, Bridges JF, Chang HY, Chang E, Nassery N, Weiner J, Chan KS. Identifying possible indicators of systematic overuse of health care procedures with claims data. Med Care 2014;52(5):157–63.

Colla CH, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Schpero WL, Rosenthal MB. Choosing wisely: Prevalence and correlates of low-value health care services in the united states. J Gen Intern Med 2014;30(2):221–8.

Miller G, Rhyan C, Beaudin-Seiler B, Hughes-Cromwick. A framework for measuring low-value care. Value Health 2018;21(4):375–379.

Segal JB, Nassery N, Chang HY, Chang E, Chan K, Bridges JF. An index for measuring overuse of health care resources with medicare claims. Med Care 2015;53(3):230–6.

Nassery N, Segal JB, Chang E, Bridges JF. Systematic overuse of healthcare services: A conceptual model. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2015;13(1):1–6.

The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/tools/downloads.aspx. Accessed February 1, 2018.

Health Resources and Services Administration. Department of Health & Human Services. Area Helath Resources Files. http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/ahrf.aspx. Accessed 1 February 2018.

McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, Hamed P, Landon BE. Delivery system integration and health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(15):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6886.

Herrel LA, Ayanian JZ, Hawken SR, Miller DC. Primary care focus and utilization in the Medicare shared savings program accountable care organizations. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1873435909. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2092-8.

Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15451981. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.w4.184.

Skinner J, Chandra A. Health care employment growth and the future of US cost containment. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1861–1862.

Feinstein A, Soulos P, Long J, et al. Variation in receipt of radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery: Assessing the impact of physicians and geographic regions. Med Care 2013;51(4):330–338. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23151590. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827631b0.

Matlock DD, Peterson PN, Heidenreich PA, et al. Regional variation in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention: Results from the national cardiovascular data registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011;4(1):114–121. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21139094. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958264.

Medicare Advantage. Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. NEJM. 2015;372:897–899.

Carter EA, Morin PE, Lind KD. Costs and trends in utilization of low-value services among older adults with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage. Med Care 2017;55:931–939.

Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Program. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(11):1815–1825.

Hollingsworth JM, Nallamothu BK, Yan P et al. Medicare Accountable Care Organizations are not associated with reductions in the use of low-value coronary revascularization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004492.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Ellenbogen for his comments on drafts.

Prior Presentations

This work was previously presented as an oral presentation at the 2016 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Mo Zhou and Allison H. Oakes are co-first authors.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 104 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Oakes, A.H., Bridges, J.F. et al. Regional Supply of Medical Resources and Systemic Overuse of Health Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 2127–2131 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4638-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4638-9