Abstract

COVID-19 has recently become a major pandemic with associated socioeconomic dimensions. Mortality statistics suggest that COVID-19 is more lethal in aged patients with comorbid conditions including hypertension. There is ongoing debate about whether the use of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are useful or hazardous in patients with COVID-19, with both narratives supported by researchers with different hypotheses. The researchers supporting the use of these medications believe ACE2 functional blockers may block cellular entry of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and thus improve patient outcomes. The counter viewpoint argues that continuous use of these drugs results in hyperexpression of ACE2 receptors on respiratory epithelium allowing easier SARS-CoV-2 intracellular entry, resulting in enhanced viral replication and tissue damage. This short review discusses the available research on the subject with the objective to consolidate data to allow formulation of recommendations on their use or otherwise. Moreover, the authors also suggest areas for future research on the subject.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of the novel coronavirus (nCoV), later named SARS-CoV-2, dates back to December 2019 when multiple cases of atypical pneumonia emerged in Wuhan, China [1]. Although initially thought to be a variant of coronavirus with moderate communicability, the virus resulted in an upsurge in mortality, especially among seniors with co-morbid conditions [2]. Within a matter of weeks the outbreak from Wuhan spread to all corners of the world and was labeled as a pandemic with millions of confirmed cases and hundreds of thousands of deaths [3]. With this growing menace, it is prudent to pinpoint the specific factors leading to adverse outcomes and the opportunities to explore from these challenges. A plethora of half-truths and low-grade evidence is emerging every day, confusing treating physicians. One example is the treatment of patients with hypertension with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), with opinions on their use ranging from harm to no harm to providing benefits with regard to COVID-19.

ACEs convert angiotensin-I to its various activated forms including angiotensin-II and angiotensin 1–9, all leading to vasoconstrictive effects (Fig. 1) [4]. SARS-CoV-2 also acts through similar receptors to enter cells where the virus preferentially replicates in respiratory epithelia [5]. There are two schools of thought regarding the role of cellular ACE2 receptors. In one, the continuous use of ACEi and ARBs increases the expression of ACE2 on cellular surfaces, which, once exposed to SAR-CoV-2, increases viral intracellular entry, thus enhancing viral replication [6]. In the other, ACE functional blockers block cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 and thus improve patient outcomes [7]. The detailed mechanism of action of ACE and angiotensin are shown in Fig. 1. The existing literature also suggests that raised ACE and angiotensin-II levels are not good prognostic indicators [8]. This short review will attempt to address and consolidate the prevailing evidence about the use of ARBs and ACEi in subjects with COVID-19.

Schematic showing the mechanism of action of angiotensin with angiotensin converting enzymes (ACE) and further downstream pathways, together with the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with the receptor. ACEi ACE inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, ATxR angiotensin receptor type-x, MAS G-protein coupled receptor

Review methodology

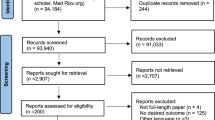

Search engines used for the study included Google Scholar and PubMed. Key search words included “COVID-19 and use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs”, along with filters including last 1 year, humans and English language. This yielded 307 articles initially (last searched 11 May 2020), which were further shortlisted as per the content. The major shortlisting criteria included specific use of ARBs or ACEi in COVID-19. Data previous to December 2019 were excluded as COVID-19 was non-existent prior to this date. The data search was later expanded to include “SARS corona and use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs”. We ended up with 17 related studies, as shown in Table 1, that specifically addressed our question.

All included studies were evaluated for the study endpoints and the evidence was graded for quality using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [9]. The evidence was graded as follows:

-

Grade A: Evidence usually derived from high quality randomized controlled trials from multiple centers.

-

Grade B: Evidence is derived from one high quality study with minimal study limitations. This research warrants further high quality trials to approve.

-

Grade C: Evidence is derived from few studies with limitations, such as case–control studies with small sample sizes, and needs further high quality research work for approval.

-

Grade D: Poor quality research originating from some expert opinion with no conduct of direct research work.

Results

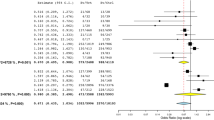

There was an understandable paucity of trials and quality evidence. We studied the data related to the two highly pathogenic coronaviruses—SARS-CoV-1 (SARS) and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19)—that have presented in the last two decades. Table 1 shows the data, supporting or otherwise, regarding the use of ACEi and ARBs in patients with SARS-CoV-1 or -2 infection.

Discussion

ACEi and ARBs are primarily used for the long-term treatment of hypertension and associated left ventricular dysfunction. In theory, it seems that the mechanistic effect of these drugs in causing ACE2 receptor up-regulation could allow SARS-CoV-2 to find more targets to attack and infect, thus worsening the patient’s condition. Conversely, avoiding the use of ACEi and ARBs in patients with hypertension could cause result in worsening of hypertension control and accelerated adverse cardiovascular effects. The data in Table 1 highlight the weaknesses in the available evidence with only one controlled trial and few studies recommending ACEi/ARB use in patients with COVID-19 [7, 16,17,18,19]. The results of the animal model study by Imai et al. suggest that administering ACEi reverses induced lung damage, suggesting that ARBs and ACEi may have utility in COVID-19 cases involving similar lung damage [11]. The recent position statements by the European Society of Cardiology and American Heart Association suggest continuing current treatment with ARBs and ACEi in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 [24, 25]. However, in our opinion, further research in COVID-19 animal models or RCTs is much needed to clarify the mechanistic details of ACE2 interactions with SARS-Cov-2 and medications and their combined interactions. Although medical science can never provide complete answers to the many questions raised, the way forward for further research needs to delineated. From this discussion and data review, it seems increased ACE2 expression is beneficial to avoid lung injury and possibly cardiotoxicity; thus it may be useful in avoiding complications in non-hypertensive subjects with COVID-19 [11, 12]. Furthermore, due to the shortcomings of the currently available data, differences in individual statements and position statements, and the repeated call or caution, results from well-designed trials are required to avoid any degree of ambiguity in short-term and possible long-term side effects [19, 20, 22, 23].

Recommendations

To conclude, we suggest the following recommendations for using ACEi and ARBs in patients with COVID-19:

-

1.

The use of ARBs in particular and ACEi may be continued in hypertensive patients with COVID-19 (evidence grade: D).

-

2.

The use of ARBs or ACEi to manage COVID-19 in non-hypertensive patients is not recommended (evidence grade: D).

-

3.

More quality trials are needed to study the beneficial and harmful effects of ACEi and ARB use in hypertensive patients infected with COVID-19 (evidence grade: C).

References

Phan T. Novel coronavirus: from discovery to clinical diagnostics. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;79:104211.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):105462.

Worldometer. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 4 Apr 2020.

Li EC, Heran BS, Wright JM. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD009096.

Danser AHJ, Epstein M, Batlle D. Renin–angiotensin system blockers and the COVID-19 pandemic: at present there is no evidence to abandon renin–angiotensin system blockers. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1382–5.

Diaz JH. Hypothesis: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of severe COVID-19. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa04.

Sun ML, Yang JM, Sun YP, et al. Inhibitors of RAS might be a good choice for the therapy of COVID-19 [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43(0):E014.

Alhenc-Gelas F, Bouby N, Girolami JP. Kallikrein/K1, kinins, and ACE/kininase II in homeostasis and in disease insight from human and experimental genetic studies, therapeutic implication. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:136.

Essential Evidence Plus. GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (A, B, C, D.). https://www.essentialevidenceplus.com/product/ebm_loe.cfm?show=grade. Accessed 11 May 2020.

Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J, et al. Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):757–60.

Imai Y, Kuba K, Penninger JM. The discovery of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its role in acute lung injury in mice. Exp Physiol. 2008;93(5):543–8.

Perico L, Benigni A, Remuzzi G. Should COVID-19 concern nephrologists? Why and to what extent? The emerging impasse of angiotensin blockade. Nephron. 2020;144(5):213–21.

Hanff TC, Harhay MO, et al. Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and the renin-angiotensin system—a call for epidemiologic investigations? 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa329.

Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1653–9.

Talreja H, Tan J, Dawes M, et al. A consensus statement on the use of angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in relation to COVID-19 (corona virus disease 2019). N Z Med J. 2020;133(1512):85–7.

Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/DDR.21656.

Batlle D, Wysocki J, Satchell K. Soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: a potential approach for coronavirus infection therapy? Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(5):543–5.

Cheng H, Wang Y, Wang GQ. Organ-protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its effect on the prognosis of COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25785.

South AM, Diz D, Chappell MC. COVID-19, ACE2 and the cardiovascular consequences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318(5):H1084–90.

Patel AB, Verma A. COVID-19 and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: what is the evidence. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4812.

Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–60.

Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease: a viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):e016219.

Rico-Mesa JS, White A, Anderson AS. Outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection taking ACEI/ARB. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(5):31.

European Society of Cardiology. Position statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang. Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

American Heart Association. HFSA/ACC/AHA statement addresses concerns re: using RAAS antagonists in COVID-19. https://professional.heart.org/professional/ScienceNews/UCM_505836_HFSAACCAHA-statement-addresses-concerns-re-using-RAAS-antagonists-in-COVID-19.jsp. Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SHK: concept, database search, manuscript writing. SKZ: database search, COVID-19 details coverage, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The review was formally approved by hospital’s ethical review committee.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

No funding was received.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, S.H., Zaidi, S.K. Review of evidence on using ACEi and ARBs in patients with hypertension and COVID-19. Drugs Ther Perspect 36, 347–350 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-020-00750-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-020-00750-w