Abstract

After participating in an experiment, people are routinely debriefed. How effective is debriefing when the experiments involve deception, as occurs in studies of misinformation and memory? We conducted two studies addressing this question. In Study 1, participants (N = 373) watched a video, were exposed to misinformation or not, and completed a memory test. Participants were either debriefed or not and then were interviewed approximately one week later. Results revealed that, after debriefing, some participants continued to endorse misinformation. Notably, however, debriefing had positive effects; participants exposed to misinformation reported learning significantly more from their study participation than control participants. In Study 2 (N = 439), we developed and tested a novel, enhanced debriefing. The enhanced debriefing included more information about the presence of misinformation in the study and how memory errors occur. This enhanced debriefing outperformed typical debriefing. Specifically, when the enhanced debriefing explicitly named and described the misinformation, the misinformation effect postdebriefing was eliminated. Enhanced debriefing also resulted in a more positive participant experience than typical debriefing. These results have implications for the design and use of debriefing in deception studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social scientists who study consequential social and cognitive processes, such as the effect of threatening information on people’s self-esteem or the ways to combat misinformation on social media, often use experimental designs involving deception (Bode & Vraga, 2018; Miketta & Friese, 2019; Murphy et al., 2020). If participants knew about threatening stimuli or false information before beginning a study, this would inhibit studying the true effects of these variables on individuals and society. Despite this, using deception in experimental studies raises several potential ethical concerns. If using deception in a study, how do researchers obtain informed consent and minimize any potential psychological, social, or emotional harms participants might experience (Benham, 2008)? Potential consequences of deception extend beyond individual participants. It may also impact perceptions of the research process in that individuals or communities may become suspicious of science or research in general (Wendler & Miller, 2004). Because of these risks, the American Psychological Association (2002) has established guidelines on the use of deception in research. These guidelines advise that researchers do not conduct a study involving deception unless it is justified by “significant prospective scientific, educational, or applied value” and that deception is explained to participants as soon as possible (p. 1070).

This procedure of explaining deception after a study has concluded is typically called debriefing. During debriefing, the APA advises psychologists to explain “the nature, results, and conclusions of the research . . . [and] take reasonable steps to correct any misconceptions that participants may have” (p. 1070). Additionally, if the researcher becomes “aware that research procedures have harmed a participant, they take reasonable steps to minimize the harm” (p. 1070). Achieving these goals through debriefing may be challenging. During debriefing, participants learn the experimenter has already been deceptive and so they may believe the debriefing is “setting them up” for another deception (Holmes, 1976). Outside of debriefing, there is ample evidence that retracted information may still affect people’s judgments and behaviors. For example, after being told at trial that a piece of evidence is inadmissible and should be disregarded, that evidence still affects juror verdicts (Steblay et al., 2006). That is, even when juries are told not to use a piece of evidence when deliberating, it still impacts verdict decisions.

Thus, although debriefing is an essential part of studies involving deception, there is at least some reason to believe that simply retracting information is not sufficient to fully restore participants to their preexperimental state. This raises potential ethical issues if debriefing does not fully ameliorate the potential harms of deception. In the current studies, we address this issue by investigating the effectiveness of postexperimental debriefing. Additionally, we focus on another, understudied aspect of debriefing. Debriefing not only serves an ethical purpose, it also serves an educational one (McShane et al., 2015). Participating in research conveys benefits to participants: they learn about the research process and the particular topic the study is about. Debriefing can help promote these goals. Thus, the current studies also investigate whether debriefing conveys educational or other positive benefits to participants.

We explore these questions specifically in the context of research on false memories and misinformation. Such research has implications both within and outside of the lab. In the lab, studying the effects of debriefing not only furthers knowledge about how false memories persist over time but also potentially informs researchers about how to design debriefing to both correct for the influence of misinformation and improve participants’ experience in a research study. Outside of the lab, the proliferation of online misinformation raises questions about how to effectively retract misinformation or “fake news” people encounter online (Lazer et al., 2018). Studying how postexperimental debriefing can effectively correct for misinformation in the lab may provide direction about how to combat misinformation people encounter online.

Debriefing effectiveness

Despite the central ethical role of debriefing in deception experiments, there has been limited research on whether debriefing fully eliminates the effect of deception on participants’ beliefs and behaviors. In one early study, participants completed a false-feedback paradigm (Ross et al., 1975). They were randomly assigned to be told they did better, worse, or about average on a novel task compared with the average student. Following this, some participants were not debriefed, some received a standard debriefing (i.e., indicating the feedback manipulation was randomized), and some received a more detailed, process-based debriefing. Results showed that the effect of the false feedback persisted even after the standard debriefing. However, the process-based debriefing was more effective in eliminating the persistent effects of the manipulation.

Most of the early work on postexperimental debriefing showed that standard debriefings are generally ineffective in completely correcting for the influence of several kinds of manipulations (e.g., Silverman et al., 1970; Walster et al., 1967). Because of this, alterations to standard debriefings have been proposed and tested. These revised debriefings include explaining the “behind the scenes” of how a false feedback manipulation operates (McFarland et al., 2007) or conducting a more extensive, personalized debriefing (Miketta & Friese, 2019). These revisions tend to be more effective in eliminating the effects of false feedback. Despite this, perhaps because of the limited research and attention paid to the effectiveness of debriefing, revisions to standard debriefings are often not common practice.

Much of the research about the effectiveness of debriefing focuses on one particular function of debriefing: the ethical purpose to reduce harm to participants and society. However, debriefing can and does serve additional purposes. Specifically, debriefing can also serve an educational function, particularly for undergraduate students who participate in research at universities for course credit (McShane et al., 2015). Through participating in research containing deception and being effectively debriefed, participants may receive additional benefits from their research participation. During an effective debriefing, participants can learn about the research process in a way they do not in studies containing no or low-quality debriefings. Some evidence suggests that participants particularly enjoy participating in studies containing deception and feel they gain a greater educational benefit (Smith & Richardson, 1983). Debriefing may convey other positive benefits as well. For instance, people who participated in a misinformation study containing deception and then were debriefed were less likely to fall for other fake news stories in the future (Murphy et al., 2020). Thus, discussions around the effectiveness of debriefing may need to focus not only on whether debriefing serves a sufficient ethical function but also whether it conveys positive benefits to participants.

In many ways, postexperimental debriefing is similar to other paradigms in which participants are presented with false information, that information is then retracted, and the retracted information continues to influence participants’ thoughts and behaviors. This is often referred to as the perseverance effect (McFarland et al., 2007) or the continued influence effect (Johnson & Seifert, 1994). The continued influence effect is often studied in the area of misinformation, specifically, exploring whether the effect of misinformation on memory can be reduced or eliminated based on prewarnings, postwarnings, or debriefing (Ecker et al., 2010).

Reducing the misinformation effect

Generally, research has shown it is difficult to fully correct for the influence of misinformation, especially when it is presented as real-world, rather than experimentally constructed misinformation, and in specific domains, like politics (Walter & Murphy, 2018). Several factors increase the likelihood that misinformation retraction will be effective, including repeating the retraction, creating an alternative narrative, and warning people about the existence of the misinformation (Lewandowsky et al., 2012). Postexperimental debriefing can be thought of as a kind of postwarning. In line with findings that pre-warnings are generally more effective than postwarnings (Blank & Launay, 2014), research on debriefing after false memory experiments has found that participants often continue to believe in false memories even after being debriefed. In a rich false memory study with elementary school children, nearly 40% of participants continued to strongly endorse false memories of choking on candy as a child or being abducted by a UFO even after debriefing (Otgaar et al., 2009).

While some participants in false memory experiments may continue to endorse false memories after debriefing, debriefing has been shown to impact certain aspects of participants’ recollective experience. Specifically, debriefing often reduces participants’ belief in an event more strongly than it impacts their memories of an event (Clark et al., 2012). This phenomenon of “vivid recollective characteristics . . . present for autobiographical events that are no longer believed to represent genuine past occurrences” is called a nonbelieved memory (Otgaar et al., 2014, p. 349).

Nonbelieved memories can occur both spontaneously and through experimental manipulations (Otgaar et al., 2014). They occur when people retain a memory for an event but have reduced belief in its occurrence. In one study, participants were led through a suggestive interview falsely implying that they experienced a hot air balloon ride as a child (Otgaar et al., 2013). Following the suggestive interview, participants were debriefed. Of those participants who developed a false memory, over half retracted their memory after debriefing. Notably though, another 38% of participants who developed a false memory after the suggestive interview had a nonbelieved memory after debriefing. That is, debriefing reduced their belief in the false event while leaving them with remnants of a memory. Only one participant continued to believe in and remember the false event after debriefing. Studies on nonbelieved memories demonstrate that the effect of debriefing on false memories may not be as simple as just whether the debriefing works or not. Rather, debriefing can separately impact participants’ beliefs and memories for false events.

Research on postwarnings and nonbelieved memories help illuminate how memories are impacted when misinformation is retracted. These two paradigms share several similarities. In both, participants are exposed to suggestion or false information, this information is then retracted, and the effect on memory is measured. Generally, these two bodies of work demonstrate that retracting information does reduce reliance on false information, but it often does not completely eliminate the effect of false information on memory.

However, these two paradigms also differ in several key ways. Studies on nonbelieved memories typically focus on autobiographical experiences often using paradigms like imagination inflation or rich false memory implantation (Otgaar et al., 2014). In these paradigms, retraction typically comes in the form of a debriefing from the experimenter (Clark et al., 2012). Nonbelieved memories are assessed by separately measuring both participants’ memory and beliefs about an event. On the other hand, warning studies typically use the three-stage misinformation paradigm and measure misinformation endorsement by asking participants directly about their memory for the target item (Echterhoff et al., 2005; Walter & Murphy, 2018). Retraction of information in postwarning studies can come from a variety of sources, including through social discrediting of the misinformation source or through the experimenter themself.

One model that provides an overarching, theoretical explanation for these differing methods of studying the retraction of false information is the SCOboria social-cognitive dissonance model (Scoboria & Henkel, 2020). This model proposes a process for “what happens when people receive disconfirmatory social feedback about events that they remember happening to them” (p. 1244). The model posits that when people receive feedback that a genuine memory they hold may not be true, this results in both intrapersonal and interpersonal dissonance. Intrapersonal dissonance is resolved by comparing aspects of the feedback (e.g., quality and credibility) versus aspects of the memory (e.g., memory strength). Interpersonal dissonance is resolved by comparing the costs and benefits of agreeing with or refuting the feedback on the person’s relationship with the feedback giver. People are motivated to resolve the unpleasant state of dissonance by weighing these factors and either defending the memory, denying the feedback, complying with the feedback, or relinquishing the memory. If, for instance, a participant judges that the feedback quality outweighs their memory quality and the costs of agreeing with the feedback are low, they may relinquish the memory. If their memory quality outweighs the feedback quality and the costs of agreeing with the feedback are high, then participants might defend the memory.

This model may help explain how debriefing quality can impact memory. If debriefing is credible, persuasive, and delivered by a person in a position of power, this increases the likelihood participants will comply with the feedback or relinquish the memory (Scoboria & Henkel, 2020). On the other hand, if the initial suggestion is strong and thus participants develop a strong false memory, then the feedback given through debriefing may not be strong enough to outweigh memory strength in resolving intrapersonal dissonance.

The current studies

The current studies build on approaches from different false memory paradigms to explore the effectiveness and potential positive benefits of debriefing in a misinformation study. Extant research on nonbelieved memories has demonstrated that debriefing tends to be more effective in reducing belief, but not memory in false events. This distinction between memory and belief is critical in developing a more nuanced understanding of the effect of feedback on memory. However, the current studies used a different approach than the nonbelieved memory literature to study the retraction of misinformation from a different perspective. For instance, one participant in a previous study with a nonbelieved memory of a hot air balloon ride reported, “Well, if my father told you that I did not experience a hot air balloon ride, then he must be telling the truth. But I really still have images of the balloon” (Otgaar et al., 2013, p. 721). From an applied perspective, what would happen if that person were conversing with a friend who asked them whether they had ever ridden on a hot air balloon or not? In the current studies, we used a misinformation paradigm often used in postwarning studies as our goal was to directly measure endorsement of the misinformation items.

Across two studies, participants completed a typical three-stage misinformation paradigm. They were then debriefed or not debriefed and approximately one week later completed a follow-up memory test. In Study 1, we compared the effect of no debriefing to the effect of typical debriefing in an initial study designed to be a pilot test of the effects of debriefing in a misinformation experiment. Participants came into the lab to complete Session 1 and were debriefed by a research assistant in person to ensure participants attended to the debriefing. About one week later, they completed an online follow-up test to explore the effect of debriefing on memory.

In Study 2, we developed and tested a novel, enhanced debriefing script in a more robust study design. In this study, the enhanced debriefing was compared against both a typical debriefing and a no debriefing condition. Study 2 was conducted fully online to explore whether debriefing without the presence of an experimenter would impact the results. We predicted that the misinformation effect would persist postdebriefing for the typical debriefing script in both studies but that the misinformation effect would be attenuated by the enhanced debriefing in Study 2.

In both studies, we explored not only whether debriefing was effective in reducing the misinformation effect over time, but also whether participating in misinformation research conveyed positive benefits for participants such as improving their experience in the study and increasing the educational benefits received from participation. We also tested whether participating in and being debriefed from a false memory study would improve participants understanding of how memory works (Murphy et al., 2020). There has been much discussion in the empirical literature about people’s understanding of memory accuracy and malleability (Brewin et al., 2019; Otgaar et al., 2021). In daily life, through online news or social interaction, people are frequently exposed to misinformation. This misinformation can have consequences in important domains like health, politics, and education. We explored whether learning about false memories through participating in an experiment containing deception would impact participants’ beliefs about this important issue. If debriefing has these positive effects, this benefit may help offset potential negative consequences if the misinformation has continued influence over time in an Institutional Review Board (IRB) risk-benefit analysis.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students recruited from a large, public university and received course credit for their participation. Of the 402 participants who completed Session 1, 389 completed Session 2. Five participants were removed from analyses for technical issues when running the study, nine participants for withdrawing their consent after debriefing, and two for failure to complete Session 2 on time, resulting in a final sample of 373 (82% female). Participants were mostly young (M = 21.18 years, SD = 3.93) and ethnically diverse (53% Asian/Asian American, 27% Hispanic/Latino, 11% White/Caucasian).

Materials and procedure

Session 1

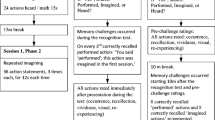

Participants came into the lab for Session 1 and watched a 45-s video (see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information for the study flow chart). The video depicted a man performing a card trick in a park for a small audience (Kralovansky et al., 2011). The camera then panned to the side to show a woman yelling incoherently at another man. A male thief then approached this man and stole something out of his bag. The thief and the woman then run off. Following the video, participants completed several filler tasks (e.g., personality measures) to create a short retention interval (~5–10 minutes) before the memory test.

Participants then completed a multiple-choice memory test about the video (see Appendix S1 in the Supporting Information). Following each question, participants rated their confidence in their answer on a sliding scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident). Participants were randomly assigned to complete this memory test in one of two conditions: misinformation or control. In order to maximize power in the misinformation condition, we used modified random assignment on a 1:3 (control:misinformation) ratio. For every one person assigned to the control condition, three were assigned to the misinformation condition.

There were two critical items in this study: the color of the woman’s jacket and the item the thief stole. Misinformation was suggested through the use of leading questions. In the video, the woman’s jacket was gray, but the misinformation suggested it was red. In the misinformation condition, one of the questions read: “Think about the woman in the red jacket that was screaming at the man; what color hair did she have?” In the control condition, this question was asked in a nonleading manner: “Think about the woman that was screaming at the man; what color hair did she have?” The second misinformation item was about the item the thief stole from the man’s bag. In the misinformation condition, the leading question suggested the thief stole a camera when he actually stole a wallet. In the control condition, this question was asked in a nonleading manner. All other questions were nonleading and identical in both conditions.

The final two questions of the memory test served as our test questions and were the same for both conditions. These questions tested for endorsement of the misinformation (e.g., “What color was the jacket of the woman screaming at the man?”). Each question had three response options: the misinformation response, the correct response, and a novel lure. Participants then completed a demographic questionnaire and were ostensibly finished with the study.

At this point, the research assistant read a debriefing script to participants (see Appendix S2 in the Supporting Information). In the control condition, the debriefing script thanked participants for their participation and reminded them about Session 2. In the misinformation condition, the debriefing script informed participants about the presence of the misinformation and why it was necessary to deceive participants about the true purpose of the study. This debriefing script was designed to be typical of that used in misinformation research and included language standard to that recommended by IRBs. Note that this study did not use a fully crossed design because participants in the control condition both did not receive the misinformation and were not debriefed. We chose not to include a misinformation/no-debriefing condition because most participants in a misinformation study fail to detect misinformation, and so we did not expect this group to differ significantly from a control group with no debriefing (Tousignant et al., 1986). In Study 2, we use a fully crossed design to explore this issue.

Following the debriefing, participants answered a few final questions (see Appendix S3 in the Supporting Information). These five questions were designed to assess participants’ subjective experiences in the study (e.g., “I learned a lot from participating in this study”).

Session 2

Participants were emailed a link to Session 2 five days after completing Session 1. They completed Session 2 at a time and place of their choosing. Participants completed Session 2 on average 5.11 days (SD = 0.48) after Session 1. At the start of Session 2, participants first completed the same memory test as in Session 1. All participants completed the control condition version of the memory test without leading questions. They then answered nine questions asking about their beliefs about how memory works (e.g., “Memory can be unreliable”; see Appendix S4 in the Supporting Information) to investigate whether participating in a misinformation experiment would affect their beliefs about memory. Finally, they were fully debriefed.

Results

Misinformation effect

Providing misinformation did indeed produce a strong misinformation effect at Session 1 for both of the critical items (see Fig. 1). We dichotomized responses of the memory test into participants who endorsed the misinformation and those who did not (i.e., chose the novel lure or the correct answer). Participants in the misinformation condition were significantly more likely to endorse the misinformation than participants in the control condition for both the jacket question, χ2(1, N = 373) = 21.69, p < .001, φ = .24, and the item stolen question, χ2(1, N = 373) = 16.71, p < .001, φ = .21. This misinformation effect persisted even after debriefing (see Fig. 1). At Session 2, there was a statistically significant misinformation effect for both the jacket, χ2(1, N = 373) = 5.69, p = .017, φ = .12, and item stolen question, χ2(1, N = 373) = 7.89, p = .005, φ = .15.

Seventy-five percent of participants in the misinformation condition who endorsed the jacket misinformation at Session 1 continued to endorse the misinformation at Session 2. Sixty-three percent of participants in the misinformation condition who endorsed the misinformation about the item stolen at Session 1 continued to endorse the misinformation at Session 2. This indicates that the misinformation effect at Session 2 was not due to random responses—rather, it was specifically those participants who endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 continuing to do so at Session 2.

Confidence

To further explore the effect of misinformation on memory, we also assessed participants’ confidence in their responses to the jacket and item stolen questions. Our main analysis focused on how participants’ confidence in their answers to the critical questions changed over time by condition. We investigated this by conducting a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). For the jacket question, there was a statistically significant main effect of time, F(1, 371) = 5.84, p = .016, ηp2 = .02, and a statistically significant time × condition interaction, F(1, 371) = 4.03, p = .045, ηp2 = .01. Simple main effects revealed that this interaction was driven by participants in the misinformation condition. Confidence changed significantly over time in the misinformation condition, t(274) = 4.25, p < .001, d = 0.26, 95% CI [0.14, 0.38]. Participants’ confidence at Session 1 (M = 3.46, SD = 1.24) was significantly higher than their confidence at Session 2 (M = 3.13, SD = 1.40). Confidence did not change significantly over time in the control condition, t(97) = 0.25, p = .803, d = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.17, 0.22].

For the item stolen question, there was only a statistically significant time by condition interaction, F(1, 371) = 4.03, p = .045, ηp2 = .01. Simple main effects revealed that confidence did not change significantly over time in the control condition, t(97) = 0.45, p = .654, d = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.15, 0.24]. However, confidence did change significantly over time in the misinformation condition, t(274) = 3.16, p = .002, d = 0.19, 95% CI [0.07, 0.31]. Participants’ confidence at Session 1 (M = 3.26, SD = 1.38) was significantly higher than their confidence at Session 2 (M = 3.04, SD = 1.38). Overall, these results demonstrate that although the debriefing did not completely eliminate the effects of the misinformation over time, it was partially effective. Participants in the misinformation condition expressed lower confidence in their memories for the critical items after debriefing.

Further effects of debriefing

After the Session 1 debriefing, participants answered five questions about their experience in the study which we combined into a composite variable (α = .81). We found that participants in the misinformation condition reported a more positive overall experience during the study than participants in the control condition (see Table 1). This was largely driven by the fact that participants in the misinformation condition, relative to controls, reported learning more from their participation in the study.

In Session 2, participants answered nine questions about their beliefs on how memory works to explore whether participating in a misinformation experiment changed beliefs about the malleability or accuracy of memory. A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed no statistically significant effect of condition on these questions, F(9, 363) = 1.14, p = .337, ηp2 = .03. More detailed results can be found in the Supporting Information (see Table S1).

Study 1 discussion

Study 1 showed initial indications that the effects of misinformation on memory can persist after a typical debriefing. Postdebriefing, participants in the misinformation condition continued to endorse the misinformation more often than partsicipants in the control condition. Results also demonstrated evidence of the positive impact of participating in an experiment involving deception. Debriefed participants reported a more positive experience in the study, specifically reporting learning more from their study participation, compared to nondebriefed participants.

In Study 2, we aimed to develop a new debriefing script that would reduce the continued effects of the misinformation postdebriefing found in Study 1. This new, enhanced debriefing was also designed to maintain and improve the positive benefits of debriefing found in Study 1. Study 2 also improved on the methodology of Study 1 by using a fully crossed design randomizing participants to both misinformation and debriefing conditions.

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students recruited from a large, public university. Of those who completed Session 1 (N = 529), 448 completed Session 2. Four participants were removed for video issues and five for withdrawing their consent after the final debriefing, leaving a final sample of 439. An a priori data collection rule was set to reach about 85 participants per cell to have sufficient sample size in the misinformation conditions for participants who did and did not endorse the misinformation. Participants (80% female) were mostly young (M = 20.57 years, SD = 3.37) and ethnically diverse (42% Asian/Asian American, 27% Hispanic/Latino, 18% White/Caucasian).

Materials and procedure

Session 1

The procedure used in Study 2 largely mirrored that of Study 1 (see Fig. S2 in the Supporting Information for the study flow chart). Unlike in Study 1, however, participants completed Session 1 of Study 2 fully online at a time and place of their choosing. Participants initially watched a mock crime video, completed filler tasks, and answered a memory test. Participants were again randomly assigned to complete the memory test in one of two conditions (misinformation or control) in the same manner as Study 1. Unlike in Study 1, we did not use modified random assignment. Participants were randomly assigned to all conditions on an even basis. They then completed demographic questions.

Following the memory test, all participants were randomly assigned to one of three debriefing conditions: no debriefing, typical debriefing, or enhanced debriefing (see Appendix S5 in the Supporting Information). The no debriefing and typical debriefing conditions were the same as in Study 1. The new, enhanced debriefing contained the same general material as the typical debriefing. Additionally, it included information about the consequences of memory errors in the form of eyewitness misidentifications and a more detailed description of how such errors occur. The enhanced debriefing specifically named one of the two pieces of misinformation (item stolen) and assured participants that memory errors were normal. Only one piece of misinformation was named so we could compare whether specifically naming the misinformation impacted later responses. All three debriefings were broken into small chunks across several pages and participants were required to stay on each page for several seconds to ensure they did not click through the debriefing. After debriefing, all participants answered three questions assessing how well they attended to the debriefing script (e.g., “I paid a lot of attention to this information”).

Finally, participants answered a series of questions about their experience in the study (see Appendix S6 in the Supporting Information). In addition to the questions asked in Study 1, we added several new items including two questions evaluating the debriefing (e.g., “I feel like I understand what the researchers were trying to find out in this study”) and six questions about the educational benefit of participating in the study. In addition to these self-report measures, we also included a behavioral measure of engagement in the study. On the final page of Session 1, we told participants that, in past studies, some people were interested in the results of the experiment. If participants were interested in learning about the study after it was published, they were instructed to click on the link provided. This link would direct them to a new webpage where they were instructed to enter their email address to receive more information.

Session 2

A link to complete Session 2 was emailed to participants one week after Session 1. Participants completed Session 2 on average 7.90 days (SD = 1.25) after Session 1. The procedure was the same as that of Session 2 of Study 1, except that the memory belief questionnaire was changed to focus more on questions about memory malleability rather than traumatic memories (see Appendix S7 in the Supporting Information). For example, we removed statements such as “repressed memories can be retrieved in therapy accurately” and added statements such as “once you have experienced an event and formed a memory of it, that memory does not change.”

Results

Misinformation effect

Our materials were again successful in eliciting a typical misinformation effect during Session 1. For both the jacket, χ2(1, N = 439) = 32.43, p < .001, φ = .27, and item stolen questions, χ2(1, N = 439) = 43.80, p < .001, φ = .32, participants in the misinformation condition were significantly more likely to endorse the misinformation than participants in the control condition.

We next explored whether the misinformation effect shown in Session 1 persisted into Session 2 by conducting separate chi-square tests for each debriefing condition. For the jacket question (see Fig. 2), there was a statistically significant misinformation effect in Session 2 in the no debriefing condition, χ2(1, N =144) = 5.23, p = .022, φ = .19, in the typical debriefing condition, χ2(1, N = 146) = 4.12, p = .042, φ = .17, and in the enhanced debriefing condition, χ2(1, N = 148) = 4.20, p = .040, φ = .17.

However, a different pattern emerged for the item stolen question (see Fig. 3). We found a statistically significant misinformation effect for those in the no debriefing condition, χ2(1, N = 144) = 20.74, p < .001, φ = .38, and those in the typical debriefing condition, χ2 (1, N = 146) = 13.70, p < .001, φ = .31. No statistically significant misinformation effect occurred for those in the enhanced debriefing condition, χ2 (1, N = 148) = 0.28, p = .597, φ = .04. Thus, the enhanced debriefing was effective in mitigating the misinformation effect over time only for the item that was specifically named in the debriefing.

These analyses demonstrate an overall misinformation effect across all participants but do not show the pattern of how participants changed their responses over time. Table 2 displays how participants in the misinformation condition responded across the two sessions. So, for instance, 77% of participants in the misinformation/no debriefing condition that endorsed the jacket misinformation at Session 1 continued to do so at Session 2. Consistent with earlier analyses, participants remained largely consistent in their responses over time. If a participant did not endorse the misinformation at Session 1, they largely did not at Session 2. Similarly, if a participant did endorse the misinformation at Session 1, they typically also did in Session 2. This pattern noticeably diverges only for participants in the misinformation/enhanced debriefing condition for the item stolen question. Only 18% of these participants who endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 went on to endorse it at Session 2. For all other groups, 65% or more of the participants that endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 also did so at Session 2.

Confidence

To explore how confidence changed over time in the misinformation and debriefing conditions, we conducted a three-way repeated measures ANOVA. For the jacket question, only the time by misinformation condition interaction was statistically significant, F (1, 432) = 4.04, p = .045, ηp2 = .01. Simple main effects revealed that there were no significant differences between confidence at Session 1 and Session 2 for the control condition, t (226) = 1.18, p = .240, d = 0.08, 95% CI [-0.05, 0.21]. Participants in the misinformation condition did show significant confidence change over time, t (210) = 3.95, p < .001, d = 0.27, 95% CI [0.13, 0.41]. Participants’ confidence at Session 1 (M = 3.31, SD = 1.27) was significantly higher than their confidence at Session 2 (M = 2.96, SD = 1.28). This replicates the results of Study 1.

We then conducted a parallel three-way ANOVA for the item stolen question. Only the two-way interaction between time and debriefing condition emerged as statistically significant, F (2, 432) = 12.01, p < .001, ηp2 = .05. Simple main effects revealed this interaction was driven by participants in the enhanced debriefing condition. Participants in the enhanced debriefing condition reported significantly higher confidence at Session 2 (M = 3.77, SD = 1.26) than at Session 1 (M = 3.28, SD = 1.43), t (147) = 4.10, p < .001, d = 0.34, 95% CI [0.17, 0.50].

To further explore the effects of debriefing on confidence, we measured confidence change in the enhanced debriefing condition based on participants’ responses to the memory test (see Table S2). Participants fell into one of four groups: misinformation response at both time points, nonmisinformation response at both time points, misinformation response at Session 1 and nonmisinformation response at Session 2, or nonmisinformation response at Session 1 and misinformation response at Session 2. Two notable findings emerged in the enhanced debriefing condition. For participants who received the enhanced debriefing and did not endorse the misinformation at either time point, their confidence increased significantly from 3.37 (SD = 1.43) at Session 1 to 3.81 (SD = 1.28) at Session 2, t (109) = 3.61, p < .001, d = 0.34, 95% CI [0.15, 0.54]. Participants who initially endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 but then did not at Session 2 showed significant confidence increase over time, t (21) = 2.37, p = .027, d = 0.51, 95% CI [0.06, 0.95]. This indicates that not only did the enhanced debriefing for the item stolen question eliminate the effect of the misinformation, but it also had other positive effects. Specifically, it enhanced the memory quality of participants who never endorsed the misinformation at all.

Further effects of debriefing

Unlike in Study 1, participants in Study 2 read the debriefing script on their own. After debriefing, participants answered three questions measuring the extent to which they attended to the debriefing script. We created a composite variable of these questions (α = .84) to test whether those who read a longer debriefing (i.e., typical debriefing and enhanced debriefing conditions) paid less attention to the debriefing information than those who were in the shorter, no debriefing condition. Results of a one-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences in amount of attention given to the debriefing between the debriefing conditions, F(2, 436) = 0.40, p = .672, ηp2 = .002.

To investigate the additional consequences of debriefing, we again created a composite variable based on the five study experience questions (α = .77). Replicating the results of Study 1, participants in the typical debriefing condition rated their experience in the study more positively than those in the no debriefing condition (see Table 3). Moreover, the enhanced debriefing resulted in a more positive participant experience than the typical debriefing. This was again primarily driven by the fact that participants in the enhanced debriefing condition reported learning more from the study than participants in either the no debriefing or typical debriefing conditions. Participants in the enhanced debriefing condition also felt the study made a greater scientific contribution than participants in the no debriefing or typical debriefing conditions. This provides initial evidence that not only was the enhanced debriefing successful in eliminating the misinformation effect over time, but it also resulted in more benefits to participants.

In Study 2, we also explored participants’ perceptions of the debriefing and the educational benefit they received from participating in this study. To assess debriefing experience, we combined the two debriefing experience questions into a composite variable (α = .90). Overall, we found that participants in the two debriefing conditions reported a more positive perception of the debriefing (see Table 4). However, we found no significant improvement in the enhanced debriefing compared with the typical debriefing on this composite measure.

We further tested the potential positive consequences of debriefing by asking participants about the educational benefits of participating in the study. As these questions each asked about independent topics, we analyzed the questions individually and did not combine them into a composite variable. Overall, participants reported gaining more educational benefit in the typical and enhanced debriefing conditions compared to the no debriefing condition (see Table S3 in the Supporting Information). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the typical and enhanced debriefing on perceived educational benefit.

As in Study 1, participants answered several questions during Session 2 about their beliefs about memory. Consistent with the results of Study 1, a one-way MANOVA showed no statistically significant differences between debriefing conditions on these questions, F(14, 860) = 0.89, p = .567, ηp2 = .01 (see Table S4 in the Supporting Information).

In addition to the self-report measures in Session 1, we also included a novel behavioral measure assessing overall interest in the study. In the no debriefing condition, 17% of participants entered their email address to receive more information about the study’s results. This compared with 18% in the typical debriefing condition and 20% in the enhanced debriefing condition. This difference was not statistically significant, χ2(2, N = 439) = 0.42, p = .809, φ = .03.

General discussion

We conducted two studies exploring whether debriefing minimizes the misinformation effect over time and results in other positive benefits to participants. Results of Study 1 suggest that a misinformation effect can persist after debriefing. Five days after debriefing, the majority of participants who endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 continued to do so postdebriefing. This is consistent with past research on the continued influence effect and nonbelieved memories (Miketta & Friese, 2019; Otgaar et al., 2014). However, our results also demonstrated that, despite the continued influence of misinformation, there were notable positive benefits to participating in a misinformation study and being debriefed. Participants in the misinformation condition reported, postdebriefing, that they learned more from their participation in the study compared with the control condition. Thus, although the kind of debriefing used here may not be fully effective for one purpose (i.e., eliminating the effect of the manipulation over time), it is successful in achieving another central purpose of debriefing—providing educational benefit to participants (McShane et al., 2015). This may be especially important in studies using college students as participants, a population often used in experimental research (Arnett, 2008). Future research is needed to explore the effects of debriefing with other kinds of manipulations as well as the effect of debriefing in other, commonly used, experimental samples (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk).

Given the findings of Study 1, we developed a new debriefing script that aimed to maintain or improve the educational benefit of debriefing, but also reduce the misinformation effect over time. Our new, enhanced debriefing was successful in meeting these goals, specifically for the misinformation item that was explicitly named and described in the enhanced debriefing (i.e., the item stolen question). For this question, the enhanced debriefing eliminated the effects of the misinformation at Session 2. Moreover, participant confidence ratings indicate that specifically naming the item not only reduced the misinformation effect but also strengthened the memory of participants that never endorsed the misinformation. However, for the item that was not specifically named in the enhanced debriefing, a significant misinformation effect persisted over time.

These results are consistent with the SCOboria social-cognitive dissonance model (Scoboria & Henkel, 2020). The enhanced debriefing was designed to be more persuasive and of higher quality than the standard debriefing. These changes made it more likely that the quality of the feedback would outweigh the quality of the participants’ memory in the intrapersonal dissonance section of the model. This model may also help explain why the enhanced debriefing was specifically helpful for the misinformation item that was named in the debriefing. Naming the misinformation may have both given the debriefing information more credibility and also may have weakened participants’ belief in their original memory. These factors make it more likely participants would relinquish their initial memory.

Past research has shown that naming a specific misinformation item does not always result in reduced reliance on the misinformation (Blank & Launay, 2014; Clark et al., 2012). However, in the present study, the misinformation item was not just named and described, the naming took place in the context of the enhanced debriefing. We did not test whether naming a specific misinformation item in the typical debriefing would result in the effects show here in the enhanced debriefing. Future research is needed to tease apart the independent effects of naming the misinformation and the other aspects of the enhanced debriefing.

The enhanced debriefing also conveyed other positive benefits to participants beyond the standard debriefing. Participants in the enhanced debriefing condition reported learning more from their participation in the study compared with the typical debriefing condition. Notably, both kinds of debriefing outperformed the no debriefing condition. That is, we found no empirical evidence that participating in a misinformation study was harmful to participants. Participating in a misinformation experiment did not negatively impact participants’ views about how memory works or the educational value they receive from participating in research. On all constructs we measured, the typical and enhanced debriefing showed either no added benefit or a positive benefit to participants.

Limitations

Many of the benefits of the enhanced debriefing occurred only for the misinformation item that was specifically named and described in the debriefing. The choice of which item to name in the debriefing was made at random because this was designed as a purely exploratory question. Future research is needed to explore whether some kinds of misinformation (e.g., details that are more central or peripheral) are more amenable to enhanced debriefing than others.

Although the enhanced debriefing improved some aspects of the participant experience, debriefing did not affect participants’ responses to the memory belief questions in either study. The present finding may have been due to the placement of the memory belief questions in the study. We chose to ask these questions at Session 2 to test whether there were both short-term and long-term benefits of debriefing. Because of this, it is unclear whether debriefing condition would have affected participants’ beliefs about memories if they had been assessed after debriefing during Session 1.

The current study implanted false memories using the misinformation paradigm. The event used in the study was not highly emotional nor personally consequential. This is common, although obviously not required, of false memory research using the misinformation paradigm. Other false memory paradigms implant rich false memories of autobiographical events that can be more emotional and personally consequential (Porter et al., 1999; Shaw & Porter, 2015). The potential negative consequences of continuing false memories after research participation are likely to differ based on the emotionality and consequentiality of the implanted false memory. The findings of the current research most directly address debriefing in misinformation studies and the retraction of misinformation from previously witnessed or experienced events. Future research is needed to explore the effect of debriefing on implanted memory of entirely false events (see Oeberst et al., 2021).

Implications

Although future research and replication are necessary, our results demonstrate the positive benefits to participants for increased consideration of debriefing when designing deception experiments. As shown here, small changes to the standard debriefing script not only reduced the continued influence of the manipulation over time but also conveyed additional positive benefits to participants. These positive benefits of debriefing were found both during in-person and online settings. Importantly, the increased length of the enhanced debriefing did not reduce attention to the debriefing information.

Our results may not be specific to misinformation manipulations but rather may generalize to a variety of nonmemory deception studies, although this is a proposition that would inherently require additional research to test. Past research has shown the continued effect of retracted information in domains including health care, politics, and the criminal justice system (Walter & Tukachinsky, 2020). In the context of lab studies, debriefing has been found to be ineffective for experiments including ego-threatening manipulations, stress-inducing manipulations, and social stressors (Holmes, 1973; Miketta & Friese, 2019; Walster et al., 1967).

Debriefing is often primarily discussed as an ethical requirement in studies using deception. There has been much debate about when and whether deception should be permitted and ethical review boards often heavily scrutinize potential harms of deception research (Kimmel, 2011). However, this debate often solely focuses on harms and does not consider benefits (Uz & Kemmelmeier, 2017). While there are extreme instances of harmful deception (e.g., Tuskegee syphilis study), most deceptive procedures used by psychologists are innocuous (e.g., telling participants they are in a study about learning when the study is actually about personality; Kimmel, 2011).

In the current studies, we show initial evidence that small changes to a debriefing script may help eliminate the continued influence of misinformation over time. Moreover, we demonstrate important, beneficial effects of participating in deception research. Participants reported learning more from the enhanced debriefing, a benefit particularly important for college student participants who are ostensibly participating in research for an educational purpose. We focused only on a few types of potential benefits; however, there are other potential positive effects. For instance, participants may become more understanding of memory errors in daily life or it may affect their susceptibility to misinformation and its correction in the future. These propositions obviously require further testing, but they highlight the potential for debriefing to serve as more than just an ethical tool.

References

American Psychological Association. (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57(12), 1060–1073. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1060

Arnett, J. J. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63(7), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602

Benham, B. (2008). Moral accountability and debriefing. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 18(3), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.0.0197

Blank, H., & Launay, C. (2014). How to protect eyewitness memory against the misinformation effect: A meta-analysis of postwarning studies. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2014.03.005

Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2018). See something, say something: Correction of global health misinformation on social media. Health Communication, 33(9), 1131–1140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1331312

Brewin, C. R., Li, H., Ntarantana, V., Unsworth, C., & McNeilis, J. (2019). Is the public understanding of memory prone to widespread “myths”? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(12), 2245–2257. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000610

Clark, A., Nash, R. A., Fincham, G., & Mazzoni, G. (2012). Creating nonbelieved memories for recent autobiographical events. PLOS ONE, 7(3), Article e32998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032998

Echterhoff, G., Hirst, W., & Hussy, W. (2005). How eyewitnesses resist misinformation: Social postwarnings and the monitoring of memory characteristics. Memory & Cognition, 33(5), 770–782. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193073

Ecker, U. K. H., Lewandowsky, S., & Tang, D. T. W. (2010). Explicit warnings reduce but do not eliminate the continued influence of misinformation. Memory & Cognition, 38(8), 1087–1100. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.38.8.1087

Holmes, D. S. (1973). Effectiveness of debriefing after a stress-producing deception. Journal of Research in Personality, 7(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(73)90046-9

Holmes, D. S. (1976). Debriefing after psychological experiments: I. Effectiveness of postdeception dehoaxing. The American Psychologist, 31(12), 858–867. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.31.12.858

Johnson, H. M., & Seifert, C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: When misinformation in memory affects later inferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20(6), 1420–1436. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.20.6.1420

Kimmel, A. J. (2011). Deception in psychological research—A necessary evil? The Psychologist, 24(8), 580–585.

Kralovansky, G., Taylor, H. (Writers) & Crowell, J. (Director). (2011). Remember this! [Television series episode]. In G. Kralovansky, H. Taylor (Producer), Brain Games. National Geographic Chanel

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

McFarland, C., Cheam, A., & Buehler, R. (2007). The perseverance effect in the debriefing paradigm: Replication and extension. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.010

McShane, K. E., Davey, C. J., Rouse, J., Usher, A. M., & Sullivan, S. (2015). Beyond ethical obligation to research dissemination: Conceptualizing debriefing as a form of knowledge transfer. Canadian Psychology, 56(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035473

Miketta, S., & Friese, M. (2019). Debriefed but still troubled? About the (in)effectiveness of postexperimental debriefings after ego threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(2), 282–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000155

Murphy, G., Loftus, E., Grady, R. H., Levine, L. J., & Greene, C. M. (2020). Fool me twice: How effective is debriefing in false memory studies? Memory, 28(7), 938–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1803917

Oeberst, A., Wachendörfer, M. M., Imhoff, R., & Blank, H. (2021). Rich false memories of autobiographical events can be reversed. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(13). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2026447118

Otgaar, H., Candel, I., Merckelbach, H., & Wade, K. A. (2009). Abducted by a UFO: Prevalence information affects young children’s false memories for an implausible event. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1445

Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Dodier, O., Lilienfeld, S. O., Loftus, E. F., Lynn, S. J., Merckelbach, J., & Patihis, L. (2021). Belief in unconscious repressed memory persists: A comment on Brewin, Li, Ntarantana, Unsworth, and McNeilis (2019). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621990628

Otgaar, H., Scoboria, A., & Mazzoni, G. (2014). On the existence and implications of nonbelieved memories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414542102

Otgaar, H., Scoboria, A., & Smeets, T. (2013). Experimentally evoking nonbelieved memories for childhood events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39(3), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029668

Porter, S., Yuille, J. C., & Lehman, D. R. (1999). The nature of real, implanted, and fabricated memories for emotional childhood events: Implications for the recovered memory debate. Law and Human Behavior, 23(5), 517–537. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10487147

Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self-perception and social perception: Biased attributional processes in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32(5), 880–892. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.32.5.880

Scoboria, A., & Henkel, L. (2020). Defending or relinquishing belief in occurrence for remembered events that are challenged: A social-cognitive model. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(6), 1243–1252. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3713

Shaw, J., & Porter, S. (2015). Constructing rich false memories of committing crime. Psychological Science, 26(3), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/095679761456286

Silverman, I., Shulman, A. D., & Wiesenthal, D. L. (1970). Effects of deceiving and debriefing psychological subjects on performance in later experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 14(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028852

Smith, S. S., & Richardson, D. (1983). Amelioration of deception and harm in psychological research: The important role of debriefing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(5), 1075–1082. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.5.1075

Steblay, N., Hosch, H. M., Culhane, S. E., & McWethy, A. (2006). The impact on juror verdicts of judicial instruction to disregard inadmissible evidence: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 30(4), 469–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9039-7

Tousignant, J. P., Hall, D., & Loftus, E. F. (1986). Discrepancy detection and vulnerability to misleading postevent information. Memory & Cognition, 14(4), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03202511

Uz, I., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2017). Can deception be desirable? Social Science Information, 56(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018416675070

Walster, E., Berscheid, E., Abrahams, D., & Aronson, V. (1967). Effectiveness of debriefing following deception experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6(4, Pt. 1), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024827

Walter, N., & Murphy, S. T. (2018). How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Communication Monographs, 85(3), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2018.1467564

Walter, N., & Tukachinsky, R. (2020). A meta-analytic examination of the continued influence of misinformation in the face of correction: How powerful is it, why does it happen, and how to stop it? Communication Research, 47(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219854600

Wendler, D., & Miller, F. G. (2004). Deception in the pursuit of science. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(6), 597. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.164.6.597

Author note

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1321846. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Open practices statement

Neither of the experiments reported here was preregistered. The data that support the findings of these studies are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 71 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenspan, R.L., Loftus, E.F. What happens after debriefing? The effectiveness and benefits of postexperimental debriefing. Mem Cogn 50, 696–709 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-021-01223-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-021-01223-9