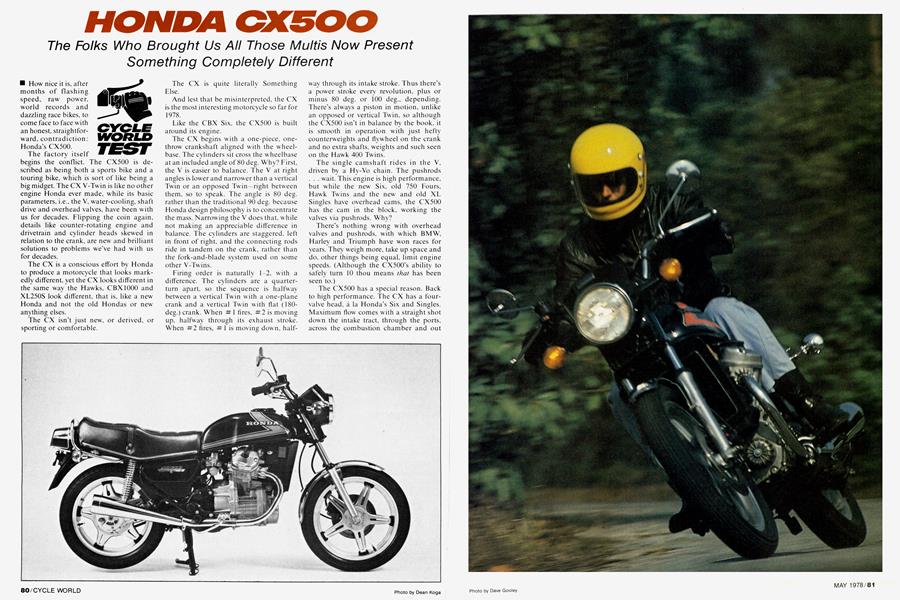

HONDA CX500

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Folks Who Brought Us All Those Multis Now Present Something Completely Different

How nice it is, after months of flashing speed, raw power, world records and dazzling race bikes, to come face to face with an honest, straightforward, contradiction: Honda’s CX500.

The factory itself begins the conflict. The CX500 is described as being both a sports bike and a touring bike, which is sort of like being a big midget. The CX V-Twin is like no other engine Honda ever made, while its basic parameters, i.e., the V, water-cooling, shaft drive and overhead valves, have been with us for decades. Flipping the coin again, details like counter-rotating engine and drivetrain and cylinder heads skewed in relation to the crank, are new and brilliant solutions to problems we’ve had with us for decades.

The CX is a conscious effort by Honda to produce a motorcycle that looks markedly different, yet the CX looks different in the same way the Hawks, CBX1000 and XL250S look different, that is, like a new Honda and not the old Hondas or new anything elses.

The CX isn’t just new, or derived, or sporting or comfortable.

The CX is quite literally Something Else.

And lest that be misinterpreted, the CX is the most interesting motorcycle so far for 1978.

Like the CBX Six, the CX500 is built around its engine.

The CX begins with a one-piece, onethrow crankshaft aligned with the wheelbase. The cylinders sit cross the wheelbase at an included angle of 80 deg. Why? First, the V is easier to balance. The V at right angles is low er and narrower than a vertical Twin or an opposed Twin—right between them, so to speak. The angle is 80 deg. rather than the traditional 90 deg. because Honda design philosophy is to concentrate the mass. Narrowing the V does that, w hile not making an appreciable difference in balance. The cylinders are staggered, left in front of right, and the connecting rods ride in tandem on the crank, rather than the fork-and-blade system used on some other V-Tw ins.

Firing order is naturally 1-2, with a difference. The cylinders are a quarterturn apart, so the sequence is halfway between a vertical Twin with a one-plane crank and a vertical Twin with flat (180deg.) crank. When # 1 fires, #2 is moving up. halfway through its exhaust stroke. When #2 fires, # 1 is moving down, halfway through its intake stroke. Thus there’s a power stroke every revolution, plus or minus 80 deg. or 100 deg., depending. There’s always a piston in motion, unlike an opposed or vertical Twin, so although the CX500 isn't in balance by the book, it is smooth in operation with just hefty counterweights and flywheel on the crank and no extra shafts, weights and such seen on the Hawk 400 Twins.

The single camshaft rides in the V, driven by a Hy-Vo chain. The pushrods . . . wait. This engine is high performance, but while the new Six, old 750 Fours, Hawk Twins and the new and old XL Singles have overhead cams, the CX500 has the cam in the block, working the valves via pushrods. Why?

There’s nothing wrong with overhead valves and pushrods, with which BMW, Harley and Triumph have won races for years. They weigh more, take up space and do. other things being equal, limit engine speeds. (Although the CX500’s ability to safely turn 10 thou means that has been seen to.)

The CX500 has a special reason. Back to high performance. The CX has a fourvalve head, á la Honda’s Six and Singles. Maximum flow comes with a straight shot down the intake tract, through the ports, across the combustion chamber and out the exhaust.

With a V across the frame and ports (or heads) located conventionally, the carbs would displace the rider’s legs and the exhaust would (in this case) run into the radiator. So Honda’s engineers skewed the ports 22 deg. off parallel. The exhausts flare out and the intakes tuck in. Neat.

But bending a camshaft drive in this direction would be complicated. So the single cam sits in the V. There are four short rocker shafts, two per head, and each shaft has two fingers for valves and one finger for a pushrod. By placing this outboard finger at just the right angle, the valve train can conform to the skewed ports. One cam plus pushrods is cheaper than two cams and chain or gear. Although we’ll never know if the skewed porting was allowed by the valve train or vice versa, it doesn’t matter because the combination works.

Carburetion is by two 35mm CV Keift ins. Big carbs. an easy way to get power. The exhaust pipes run to an expansion chamber, which Honda is pleased to call a “Power Chamber” and then to separate mufflers. Ignition is capacitor discharge.

Liquid cooling and the CX500’s astonishingly high compression ratio are another cause vs effect question.

Water cooling has become a touring byword, usually because wrapping the cylinder and heads in liquid-filled jackets is quieter.

There’s more to it than that. An engine tucked into a water jacket lives in a more hospitable and controllable environment. An air-cooled engine must be designed to flail across the Great American Desert at 8 thou and 105 deg. F„ or crawl through the slush at -5 deg. F. Inside water jackets, though, it’s always whatever the engineers desired. With less temperature variation, there’s less expansion and contraction, meaning tolerances can be closer and the engine will live longer. Weight and cost are increased, which is chiefly why sports bikes are air-cooled and some touring bikes have radiators. (Yes, a close parallel to shaft vs chain drive.)

In this case though, a bonus. Because the liquid-cooled engine can have its temperature controlled, and because Honda’s engine men have combustion chamber expertise unmatched in the world, the CX500 has a compression ratio of 10:1 and runs happily on low-lead fuel.

Remarkable. That 10:1 is as high as any mass-produced engine on the market and the other equals demand high-test gas. High compression and low-lead is the cheapest horsepower since the exhaust cutout. High compression increases power and torque and efficiency. The engine can move the bike faster or further or both and (in Honda’s case, anyway) the exhaust will still pass emissions tests.

What all this does, in closing, is deliver an odd-looking pushrod engine, two big cylinders, with almost as much power per cc as the multi-cam, semi-race Honda Six and more power per cc than most of the multi-cam Fours. Good show'.

The alternator runs off the rear of the crank, just aft of the starter ring gear. There is no provision for kick start, by the way. The CBX, the CX500 and for 1978 the GL1000 show us the future and there will be no kicking.

Primary drive and power take-off are combined, working to the right off the front of the crank. The drive is direct, gear to gear, and because of that the clutch and most of the transmission gears and the driveshaft itself rotate opposite to the engine. Boffo. Quicker than a BMW owner can say one adapts to a bike that tilts under torque, Honda transforms the driveline into a counter-rotating balancer. It works. Revving the engine at rest tips the machine opposite to engine rotation. Once underway, no sign at all.

The 5-speed transmission is conventional except maybe for a gear lever working at right angles, w'hat with the transmission aligned with the crank and the crank funning fore and aft. The rider’s foot won’t be able to tell the difference, though, because the throws are so short that the arc of travel doesn’t matter. We are told the clutch has been designed to give a broad span of engagement, about which more later.

The output shaft has its own cush drive, which must be responsible for the almost complete lack of drivetrain snatch, and then goes to a car-type universal joint. The drive shaft itself is routed through the swing arm tube to the ring and pinion.

The frame obviously comes from the folks who brought us the CBX 1000. The CX follows the same theme, with a colossal backbone, no front downtubes and the engine used for reinforcement. And the factory even calls the frame a diamond type because the mounting pattern—not the frame itself, as the term is usually applied—forms a diamond in side view.

The CX is different in that there are no secondary backbone tubes. The massive single tube and the engine itself are enough to cope with the bike’s weight, torque and cornering forces.

The CBX has its unusual frame for reasons of space, that is, containing a long engine/drivetrain within a reasonable wheelbase.

The CX500’s design comes from space utilization of a different kind. The radiator is deftly tucked away beneath the steering head, subtly blended into the bike where downtubes would otherwise be. The main frame runs fore and aft w hile the forces of the engine are bound to be side to side, so there’s a sub-frame of sorts. This goes onto the backbone and comes down and out, as wide as possible, with its lower edges bolting to the top of the V. Aft of the main subframe is a smaller pair of braces joining the rear of the backbone to the upper rear of the engine. The transmission portion of the case bolts to still another sub-frame at the swing arm pivot point.

Suspension is mostly off the shelf, with Honda’s newish FVQ two-stage rear shocks and low-friction front forks with Dacron slider bearings. Ditto the brakes, with generously-sized front disc and rear drum.

Styling is deliberate and deliberately New-Look-Honda. The CX tank is more graceful than the CBX’s, because there’s less fuel and more room for it. Then comes a seat that a full-dress Harley could take lessons from and an aft section with a bit of stowage room beneath. The seat removes with catches at the rear, after the operator unlocks a hasp sort of arrangement incorporated as part of the helmet lock at the seat’s lower left center. The rear seat has a grab rail. The fuel fills via a lid which hides a twist-off cap. The cap has one of those damnable wire catch things which requires the cap itself to dangle on the painted tank, dripping gas every time. Blah.

The most, uh, unusual bit of style is a flared and faired nacelle for the headlight, warning lights, instruments and switches.

HONDA CX500

$1898

FRONT FORKS

These Showa forks, while of conventional design, are a departure from the norm. Relatively soft spring rates are employed, with 2.6 in. of preload to restore static ride height. This is fine for the solo rider, but the addition of either a fairing or a passenger would require stiffer springs.

REAR SHOCKS

Spring and damping rates provide a comfortable ride for the one-up tourer. The addition of a passenger or baggage, however, would necessitate heavier springs and damping, as the riseand-fall action of the CX500’s shaft drive tends to emphasize shock deficiencies. A pair of adjustable shocks would be a worthwhile addition for the serious tourer. Tests performed at Number 1 Products

continued on page 86

It's plastic and extends even to the stalks carrying the front turn signals. Somewhere in the factory literature there is reference to how the designers wanted the CX500 to look different. In this area, it's different only if you’ve never seen motorcycles from the Fifties and early Sixties. No harm done, though.

Wheels are ComStar. with tubeless tires, again a new thing for a production motorcycle and welcome.

The aforementioned contradictions begin to smooth out with the specifications. The CX wheelbase is about average. At 476 lb. it's heavy for a sports bike but not that heavy. The seat height is lower than that of a Yamaha RD400. to name a traditional sporting middleweight, giving the CX a shot at the distaff and short man market. What we have is a bike fitting the middle ground in size and price.

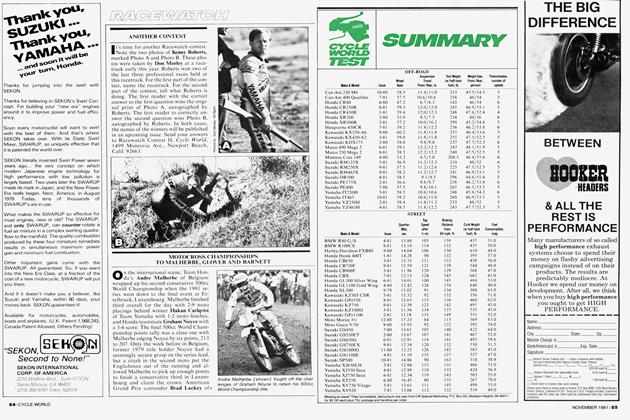

Performance? Gosh. yes. While not setting any overall records, at 13.96 sec. for the quarter mile and 104 mph in the flying half mile, the CX comes near as dammit to a tie with the Suzuki GS550. a proven roadster. And the CX outruns the RD400. the Yamaha SR500 and XS500 Twin and of course the Honda Haw ks, as well as a herd (good word choice) of heavier cruisers with larger engines and every four-wheeler this side of an $85,000 Ferrari.

The above may come as something of a surprise. Just as the distinctive looks of the CX tend to startle at first, so does the CX's muscle speak softly.

At idle and low revs the engine sound and feel are a dub-a-dub-a-dub-a: not like a vertical Twin or a Ducati or a Beemer and certainly not like a Harley and Davidson. There isn’t much actual noise and what does come through the pipes is soft and unobtrusive and not exciting. Bland.

The initial feel is touring and the new CX rider tends to move away in calm fashion. Light clutch, light throttle, light gearchange. Torque at the bottom is adequate and one need not buzz the engine. Tall gearing in top keeps the revs dow n and there you go down the road, as if on a Honda Winglet. Our tech boffin says the engine pulses and forces work in ways impossible to describe but the result is pulse rather than vibration, small amplitude and low frequency of a sort that becomes, he suggests, relaxing. And so it is. The overstuffed chair is comfy as the one in your den. The high bars fall easily to hand and the posture is right. Ride is stiff but not objectionably so and the unusual nacelle and tank become normal. Nice touring bike. this, fine for the Gold Wing owner who'd like to have something smaller for jaunts.

Now roll the throttle full open. Instant sport. The severely oversquare engine and all those valves and the big carbs are there for power and as the figures show, the CX has power. It's a more-gets-more stage of tune, with not so much a band as a constant increase up to redline. This thing w ill scoot.

Also it will handle. The ride is stifl'er than the BMW. an obvious comparison and the best ride out there. The CX is more stiffly sprung because while the wheel travel is adequate, it isn't as much as the BMW offers. With as much weight to control and less distance in w hich to do it. the CX must ride harder.

Shaft drive is different and demands its own technique. The rise and fall of the swing arm is reversed, as the shaft pushes up when a chain pulls down. They all do this: BMW. Yamaha XS750 and XS1100. Guzzi and CX.

Presumably because of the sporting suspension. the CX does not do this noticeably at touring speeds. Or maybe it's the non-surplus of torque. Either way. the new rider isn't conscious of the shaft driving . . . until he comes into a corner, banks down and zooms on through.

The CX is good at this. It feels light being rolled around the shop, comes up heavy tin the scales and heavy in closeorder parking lot drill and light again when the going gets quick. Only under full power coming out and hard braking going in does the bike rise and fall in its expected opposites. And it doesn’t much matter. Steering is quick and remains light even at full lean. Steering rake is steep, surely because the engineers dialed in enough straight-ahead stability to match the bike's top speed and that 104 is not 134. thank goodness—let them keep the rake in tight and gives a sure response when you need it. By trying really hard and using tricks, like getting 'way over in a sharp curve and rolling off on power so the chassis dropped, we touched a peg once or twice. For the record, only. Normal sport riding will never require such an extreme.

Nor was there a wobble, a shake or a hunting within the chassis or suspension. Laid full over, under full power, keeping on the proper side of the road, the CX behaved without flaw. The frame and suspension are equal to the weight and power.

Couple odd things. One is that in their quest for power, Honda's wizards packed most of it into the top. In the usual traffic situation, passing with all due speed, top gear w ill do. But w hen you really need to whip on out and around, one downshift or two w ill be required. And in tow n. say. 3040 mph. the engine isn't happy laboring in fifth. Better stay in third or fourth, where the engine is smoother and quieter.

As another unavoidable comparison, shifting the CX without skill brings out a clunk which needs no introduction. Where it comes from, also part of the comparison, is hard to say. A light, sure use of hand and foot. fine. Move too slowly or not in exact coordination and, clunk.

The factory guys say they built in what's termed a broad span of engagement for the clutch. This is so. Works great at low speeds in traffic and at maybe 5 or 6 thou when you jab the shift lever and just barely feather the clutch. You can shift so smoothly it feels like the automatic the CX is sure to have in the near future. But at wide-open throttle, 9500 and full pressure on hand and foot levers, the clutch doesn't bite. More like a slip except that it's slipping because it's supposed to take hold gradually. It adds a bit to the quarter-mile times, while also protecting the drivetrain from shock, so it may not be a flaw at all.

More in keeping with the intended use of the CX is a problem w ith equipment.

Appoint yourself a manufacturer of touring accessories. Look at the CX. Note how the mufflers sweep up. the seat sweeps down, the grab handles stick out. Where will the saddlebags go? How does one attach a luggage rack when the frame is short, the seat is long and the various lights and handles take all the space between?

A frame-mounted fairing on a bike w ith no frame in the usual place becomes a contradiction in terms. And the place where frame tubes usually are is filled w ith radiator. My word. At a time when virtually all the other factories are getting together with suppliers to make sure their buyers can find good touring equipment that fits, not only does Hondaline offer almost nothing but Honda’s middleweight tourer poses problems all its own.

Meanwhile Honda has presented us with a Twin that's as complicated as a Four. The CX500 is as big and heavy as some 750s and as fast as the 750s it’s heavier than. It'll scoot through canyons with the pocket rockets and trundle across the continent with the big cruisers. The world’s largest midget turns out to be the world's smallest giant.