The Blue ‘Un’s technical guru, Ubique, “Discusses the Improvements He Likes Best on Modern Machines, and Looks Forward to a Motor Cycle that Will Combine Speed, Comfort and Silence…

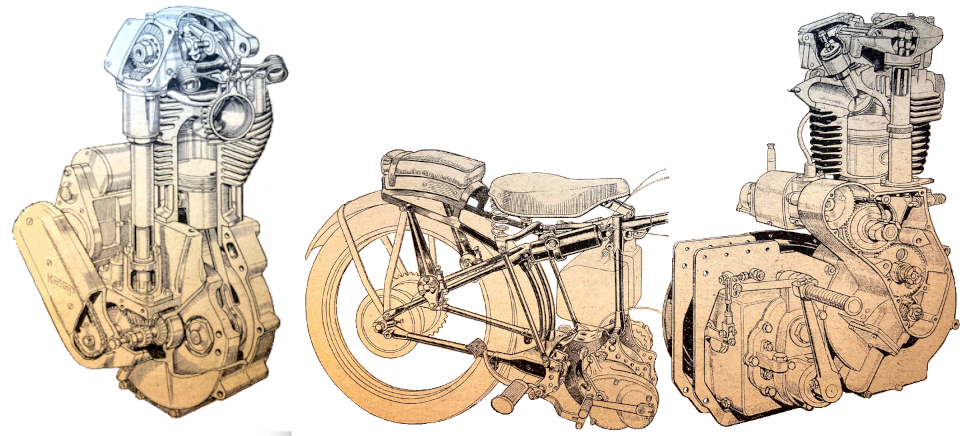

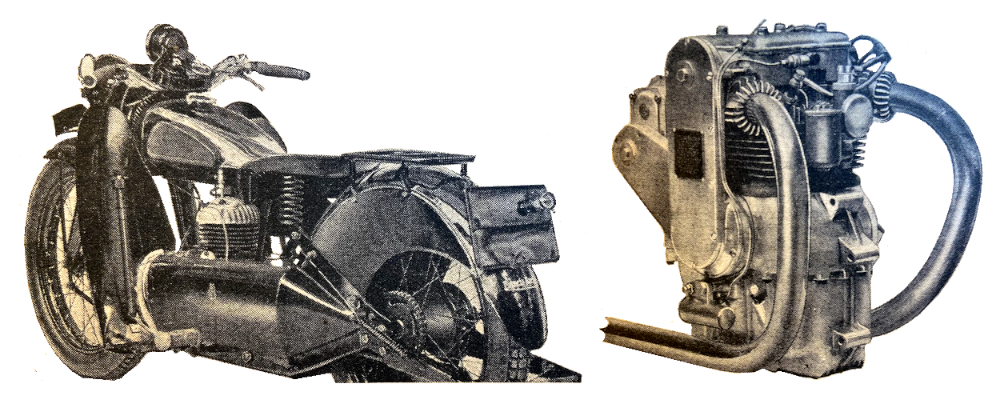

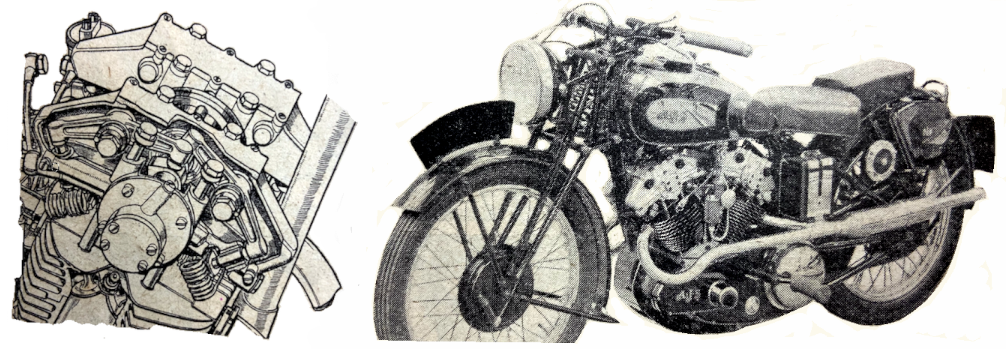

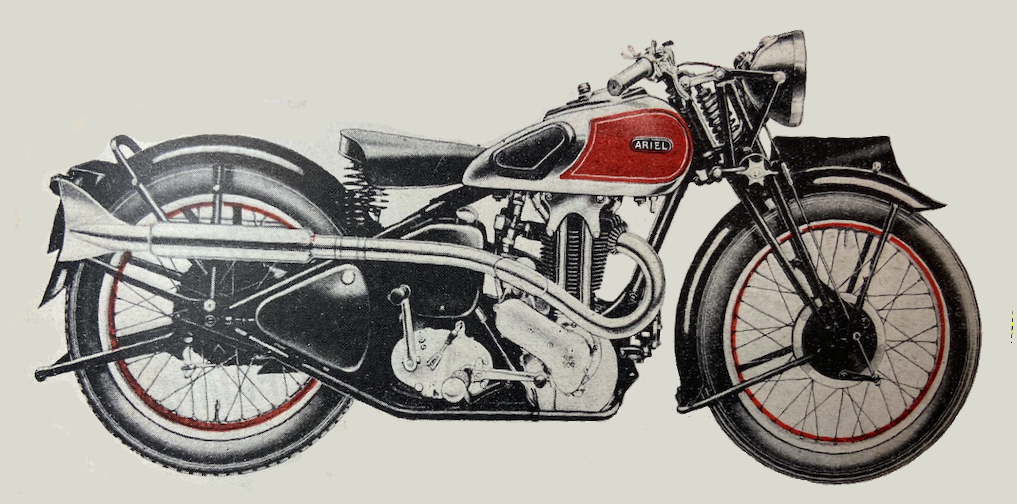

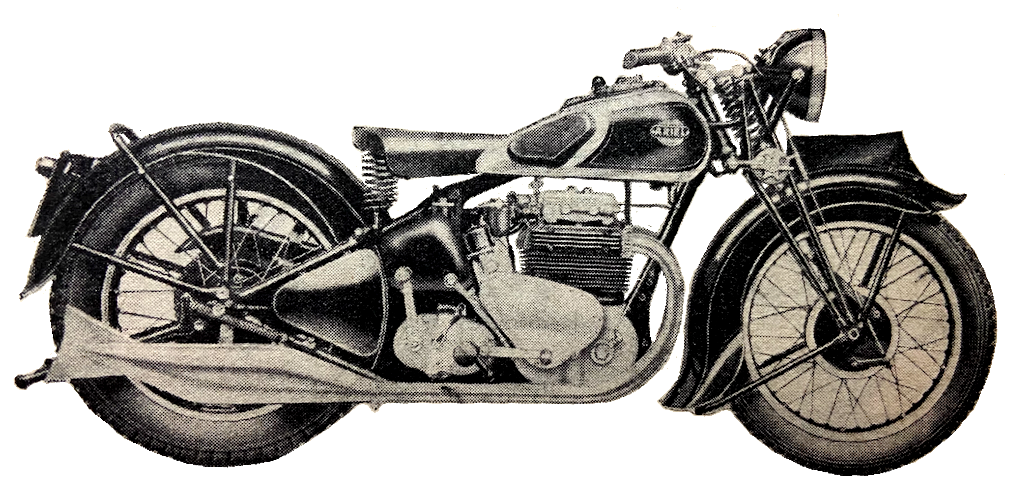

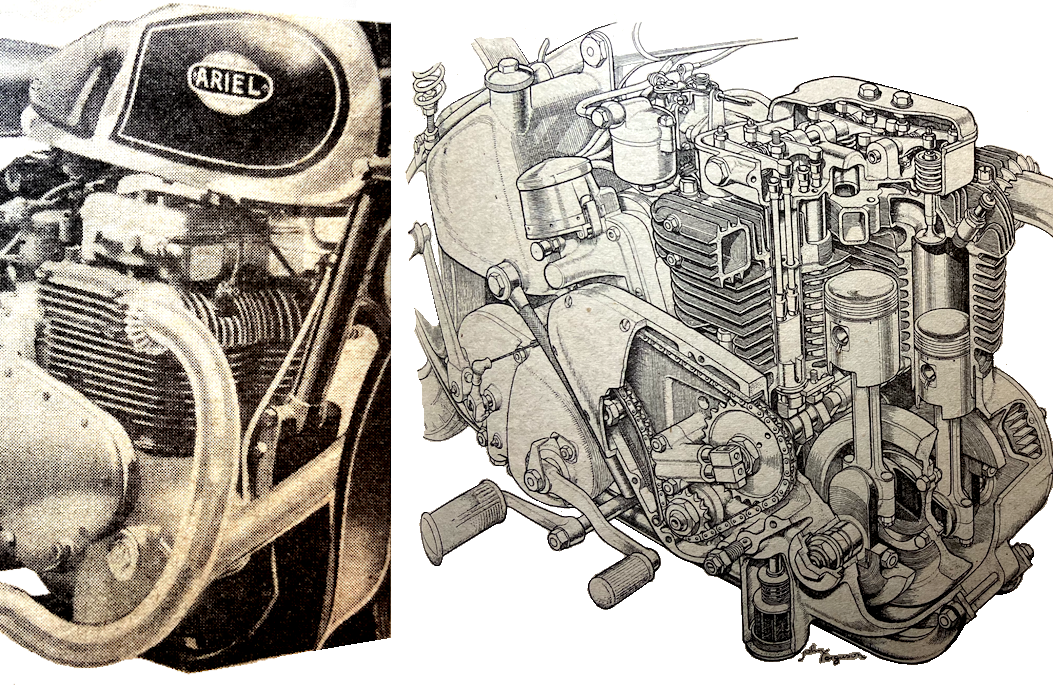

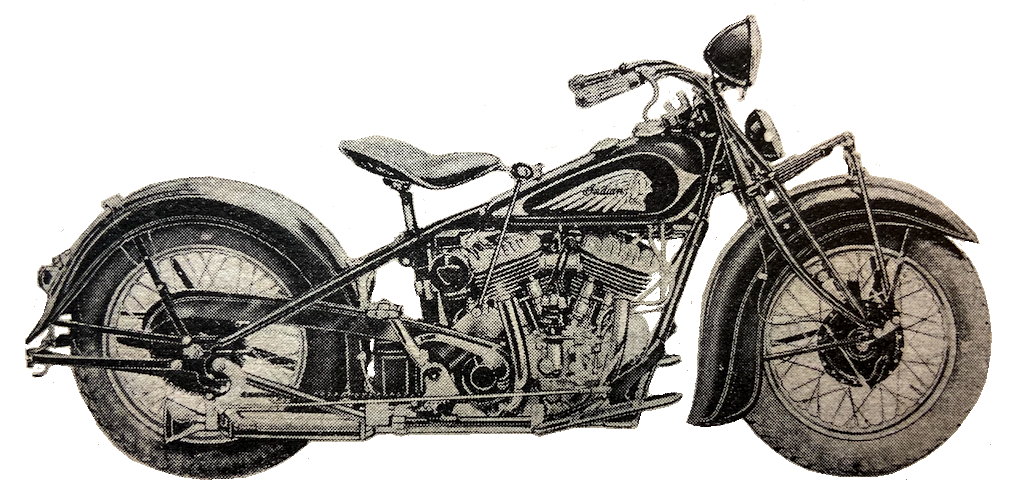

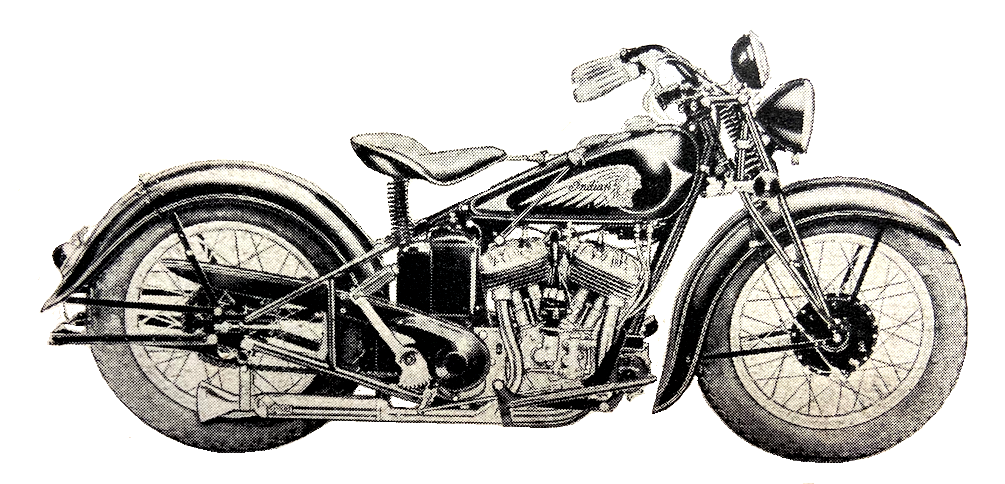

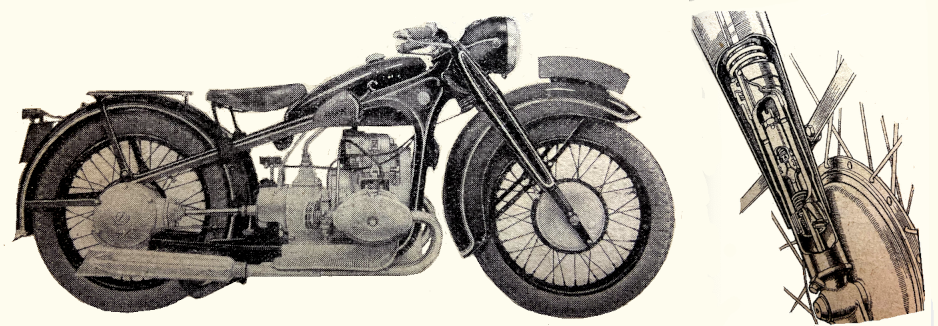

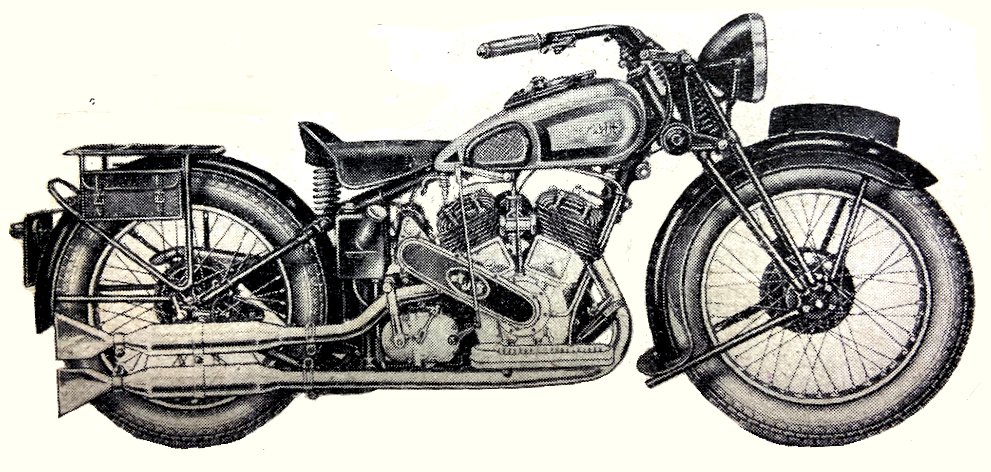

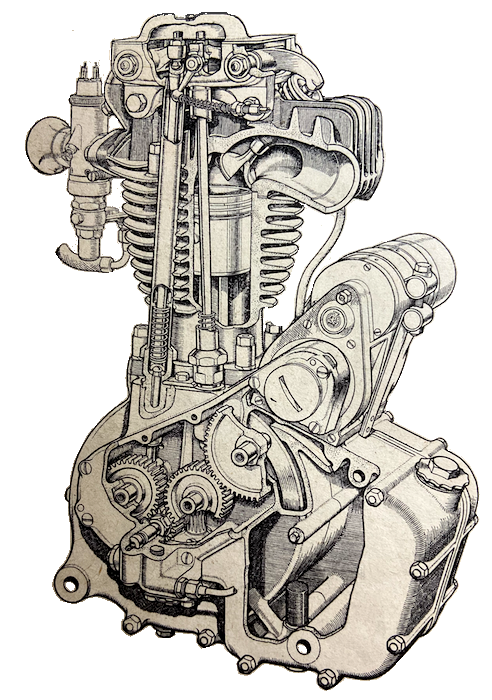

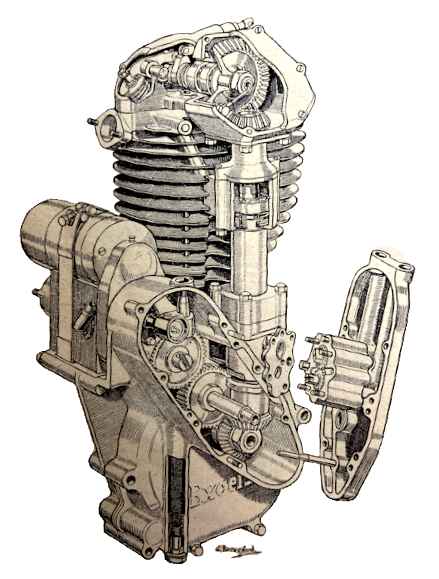

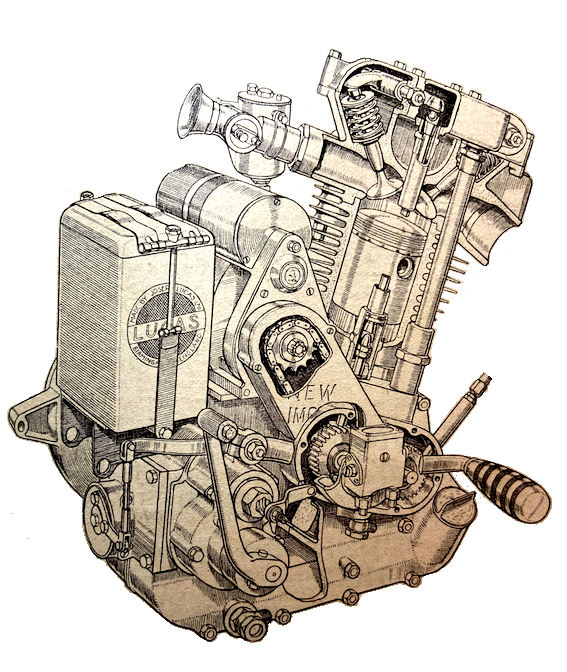

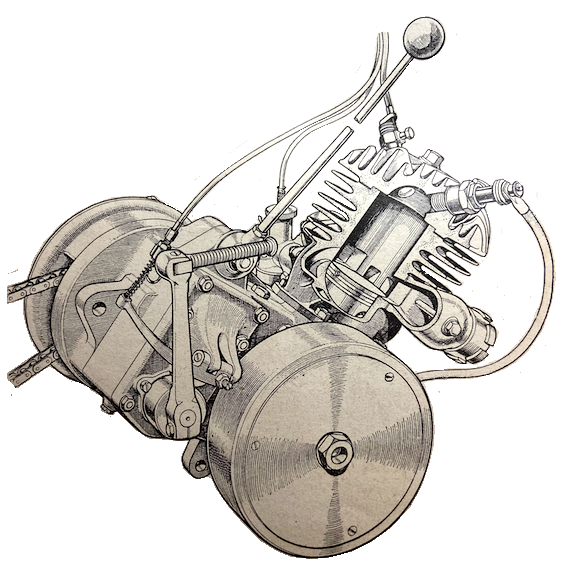

“IF YOU WERE ASKED what features you liked best on existing motor cycles, would you know where to begin? I am in that very position—I like so many things, great and small, that I have not a notion where to start. Those who are accustomed to my scribblings will expect to to have something to say about multi-cylinder engines and unit construction, so I will begin there, and get it over. My first choice would be a multi, and by that I mean something with more than two cylinders. We have two ‘fours’ on the market, and I like them both. Yes, I know my tastes are expensive, but that is a common failing with mankind. I like four-cylinder engines because they are smooth, quiet, fast, and accelerate wonderfully These are not just theories, for I have owned one of the two and ridden the other, and I have owned a third type which is now only built to special order. Next to the four I like a twin, preferably a flat twin because of its even firing and good balance. The mention of flat twins reminds me that there is a flat twin on the market with unit construction and shaft drive. Unit construction is one of my pet hobbies, because it leads to a neat, lighter, and more rigid unit, which can be just as accessible as a two unit job—vide New Imperial. I am all for unit construction, and, on

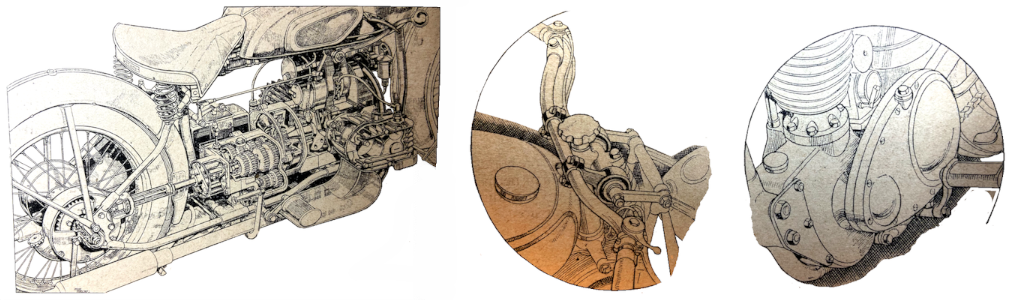

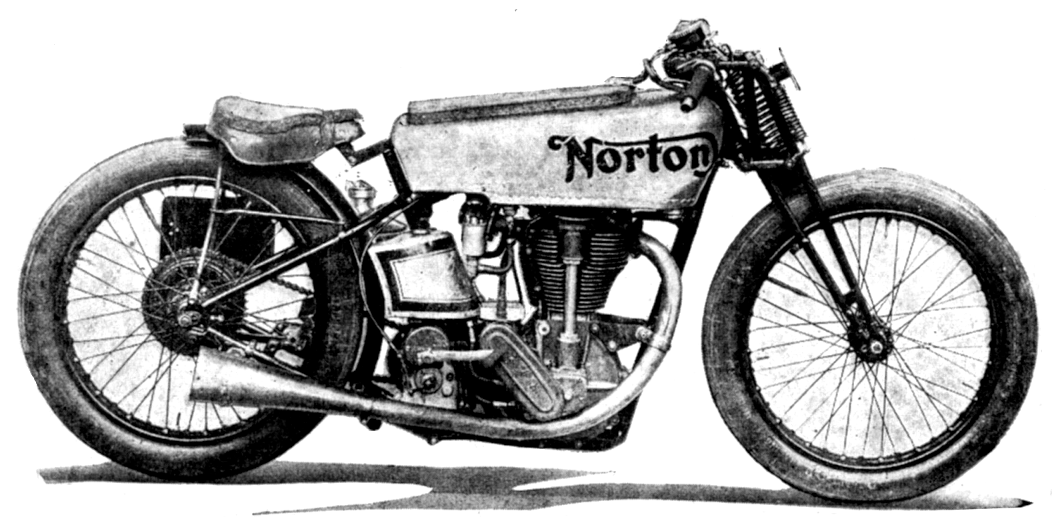

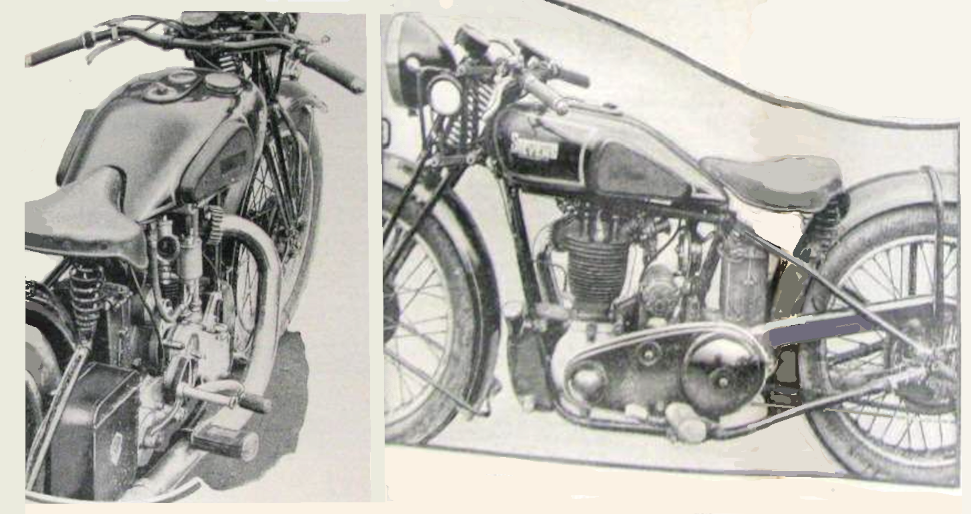

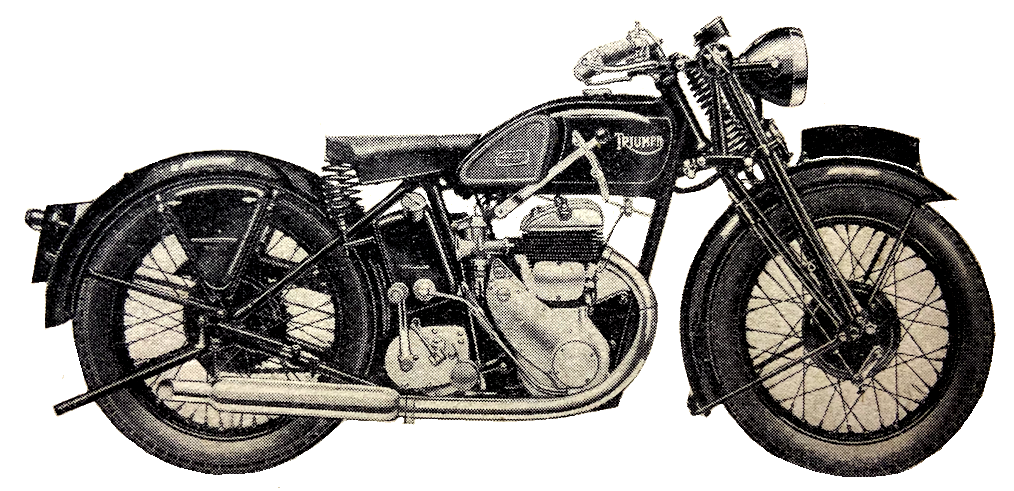

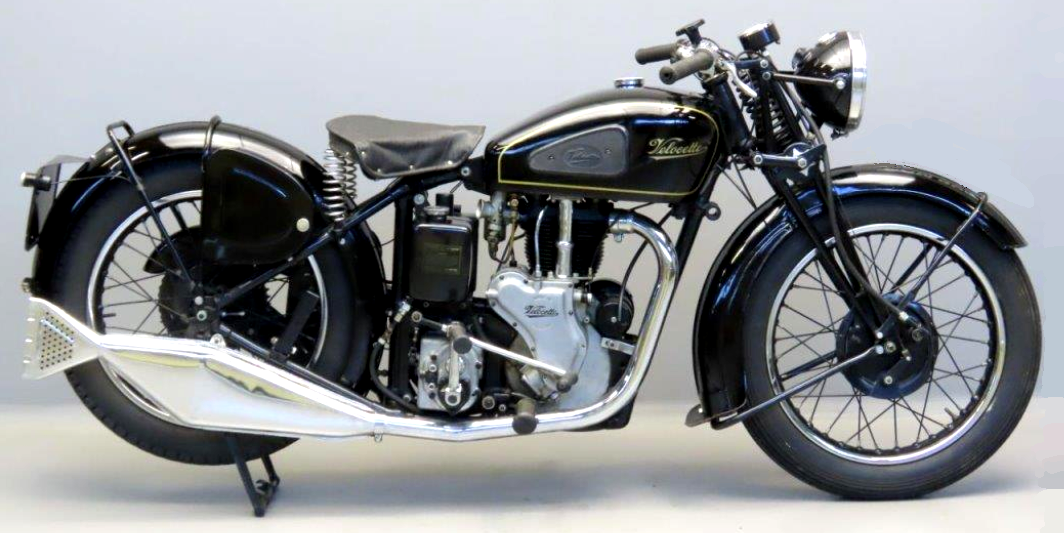

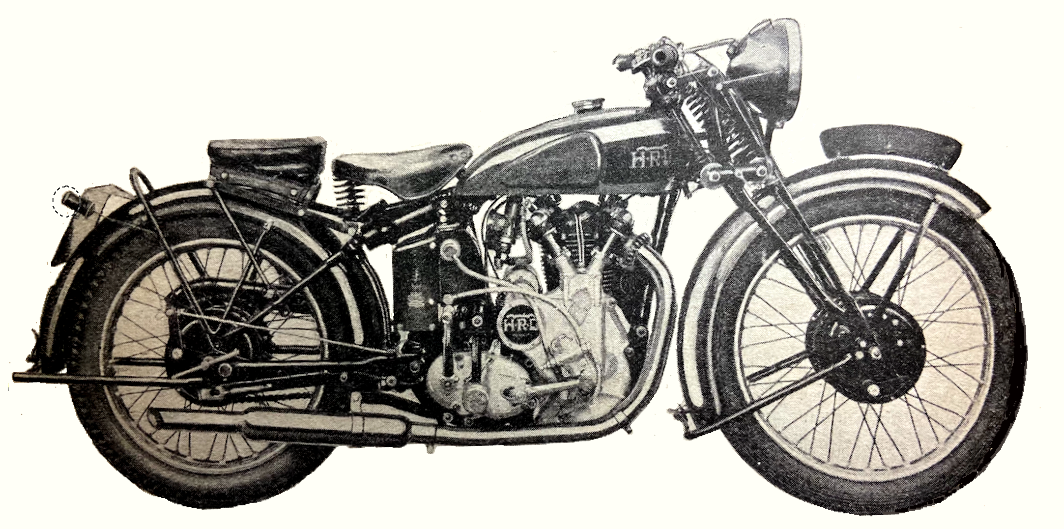

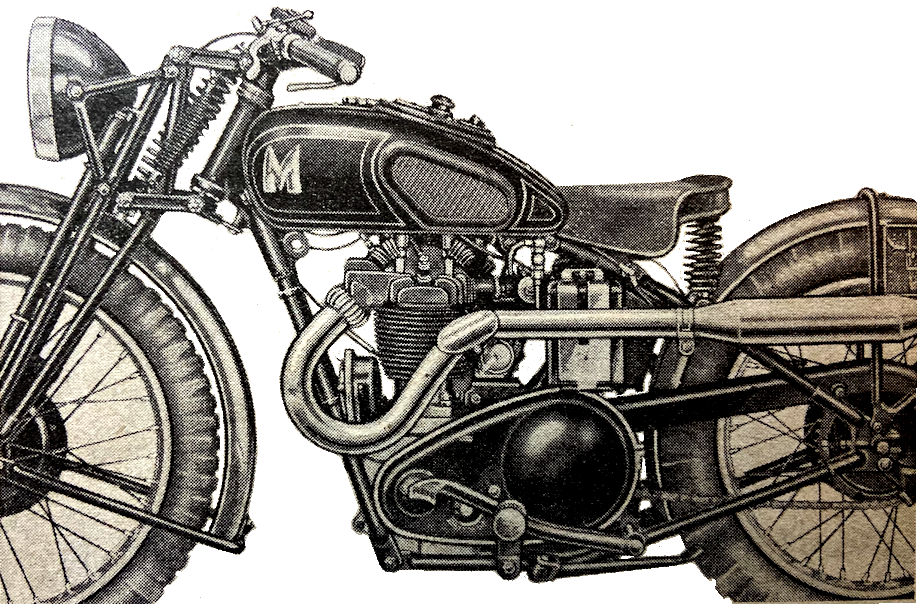

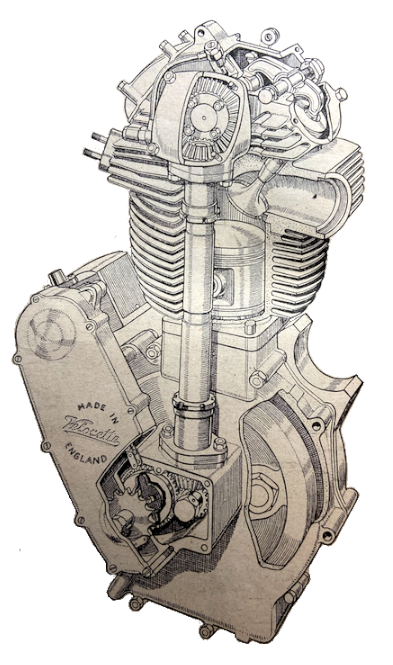

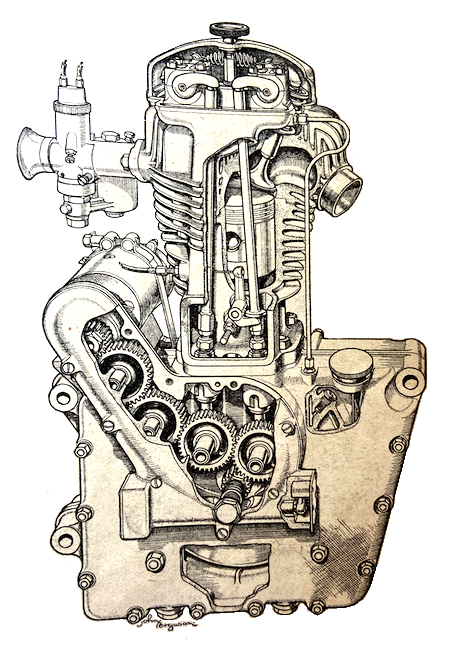

paper, admire shaft drive. In practice I like it only if there are enough cylinders and flywheel effect to make it smooth. I did not intend to get on to transmission matters so early, as I have in mind a lot more items to do with engines. First of all there is the overhead camshaft. More expense—but it seems quite obvious that with just the weight of the overhead rockers and no push rods and tappets, there is bound to be less wear on the valve gear. Further, an engine can run faster and with greater reliability for a given valve spring strength, or the same results can be obtained with lighter springs. Also, a well laid-out overhead camshaft looks so neat, does it not? Next to the overhead camshaft comes the high camshaft, such as is to be found on Velocette, Sunbeam, and Vincent-HRD models. It is less expensive and very practical. While on the subject of valves and valve gear, I like all-enclosed valve mechanism because I feel that no moving parts should be exposed to mud, dust and rain, but I also admire hairpin valve springs because most of the spring is well away from the hot cylinder head and valve stem. However, perhaps they are best kept to their own spheres, the one for touring and the other for racing. Even this is not quite right nowadays, for the Excelsior Manxman races with enclosed springs—shall we see enclosed hairpins in the near future? Another engine feature which I favour is the deeply-spigotted cylinder, which provides support where it is most needed and gives a neat and workmanlike appearance. I have already expressed a strong preference for unit construction, and this, as a rule, means a gear drive for the primary, and this also I like. But if a primary chain is employed, this, in my opinion, must be enclosed, and must run in oil. A clutch that runs in oil is often inclined to drag, and therefore I am in favour of some such scheme as that adopted by the Rudge-Whitworth people in which the clutch to all intents and purposes is oil. proof, and I am inclined to prophesy that there will be further developments in this direction. Humbly I submit that the rear chain also should also run in an oil-bath case, but Sunbeams do not appear to have many copyists. I wonder why? Of course, it involves a quickly-detachable rear wheel, but this is yet another desirable feature, so I for one do not hold that point against it. Wheels, of course, must be strong and stiff, and I like big tyres, but cannot the ensemble be made a little lighter? I am inclined to think that the use of really big tyres should enable the rims and spokes to be lightened, because the wheel in itself is smaller, and receive less shock. Present-day speeds demand big brakes, and it is just as important that the brakes should he waterproof. Further, I like the double brake lever bearing introduced by Excelsiors for the TT. In the matter of gear boxes, I am afraid that I am a bit unorthodox, for I want only three speeds. I have never found a good use for a four-speed box, except for (1) a racing machine, and (2) competition work. This in itself may be an admission of the desirability of four-speed boxes, but you who ride solo—how often do you use bottom gear? However many gears I have I

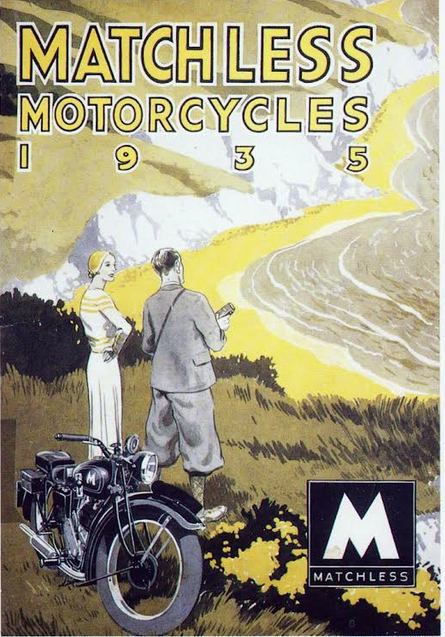

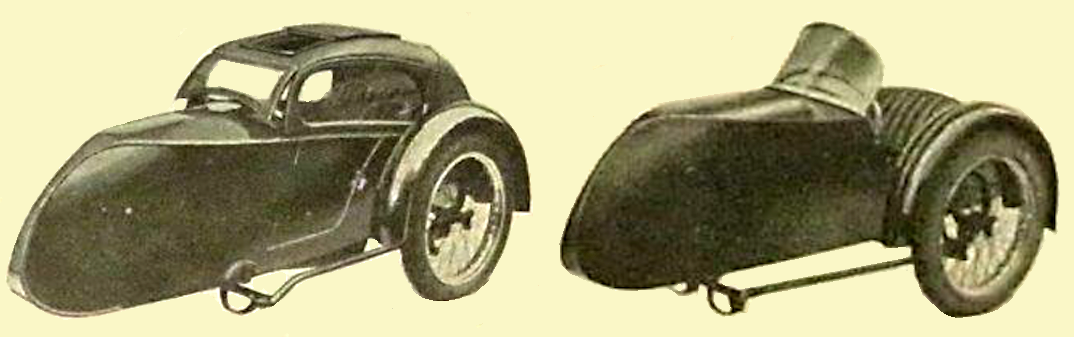

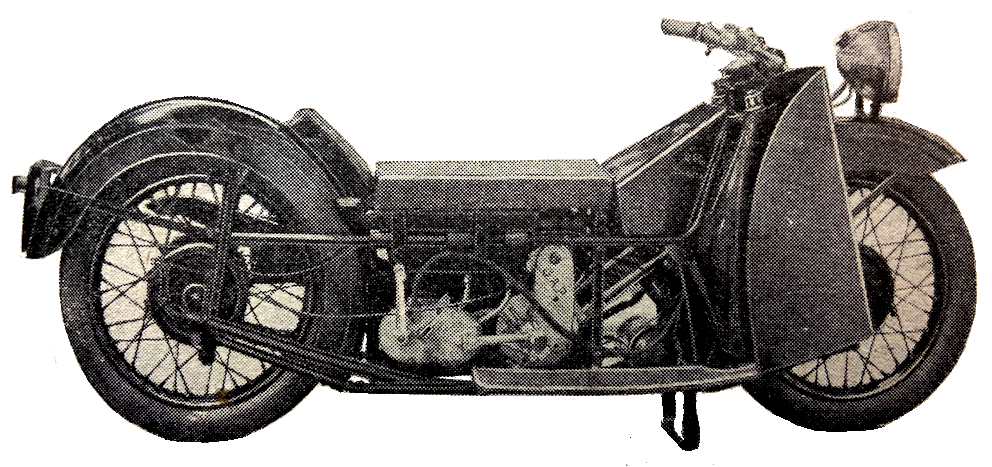

want fairly close ratios for the two top ones and a moderately low bottom ratio. The four-speed box has its advantages on a really snappy performer, for one can have three ratios close together and an emergency ratio. Also, it is undoubtedly useful on a low-powered machine, but on a slogging tourist three ratios ought to be enough for anyone, and a box of this type would be cheaper, lighter and less noisy, which means more efficiency. In any case, the gears should be foot-operated on the positive-stop principle. I have ridden many machines with spring frames. Some have been bad and some extremely good, and I think that it is fair to say that all the present-day forms are good. I have memories (years ago) of an amazingly comfortable lap round the Manx course on a Velocette fitted with a Draper spring frame, and have often been surprised that spring frames figured no little on racing machines until the last year or two. A similar type of frame has given me many a pleasant ride on Brough Superiors. Then we have the Vincent, OEC, Matchless, and New Imperial, all standardising rear springing. Why don’t we see more spring frames on the roads? In combination with a spring frame I like a long, slow front-fork action, with moderately heavy damping, and I like bottom-link forks because they remove some of the unsprung weight from the front of the machine. Another recent improvement, which I hope I may never be without, is the rubber-mounted handlebar. I have had an early Ariel bar in use for well over a year and can testify to its value, especially on long rims. Just one more matter regarding personal comfort—I like a big saddle, with one of those back rests which appear to be little more than a ledge to prevent the rider sliding rearwards. I have little time for cleaning my machine, and therefore I like an all-enclosed model that can be hosed and wiped down with a damp rag. I have one, too. My ‘Cruiser’ Francis-Barnett has excellent leg shields and mudguarding, and I have never needed waders on short journeys, whatever the weather. This all sounds rather ‘touristy’, but do not imagine that I object to fast machines—I like them. Yet I believe that speed, comfort and silence can be combined, and I think that we are getting nearer to that ideal every year. The ‘perfect’ motor cycle of the future will most certainly possess a good prop stand, although before I get too creaky in the joints I am hoping—and even expecting—to see such an increase in the use of light alloys that the prop stand will not be quite so urgently needed as it is now. Of course, the machine most be silent. I am afraid I cannot give an example of an existing machine in this case because none of them is as quiet as I should like.”

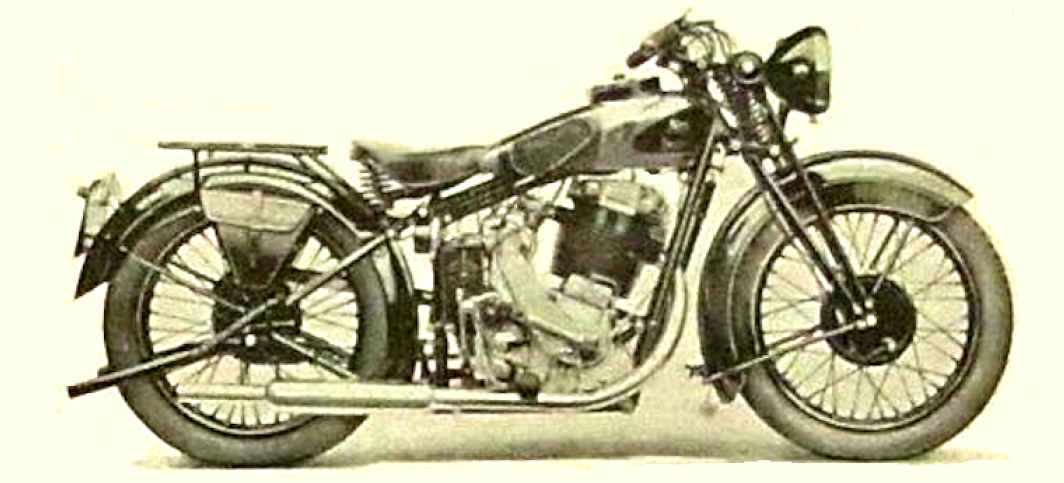

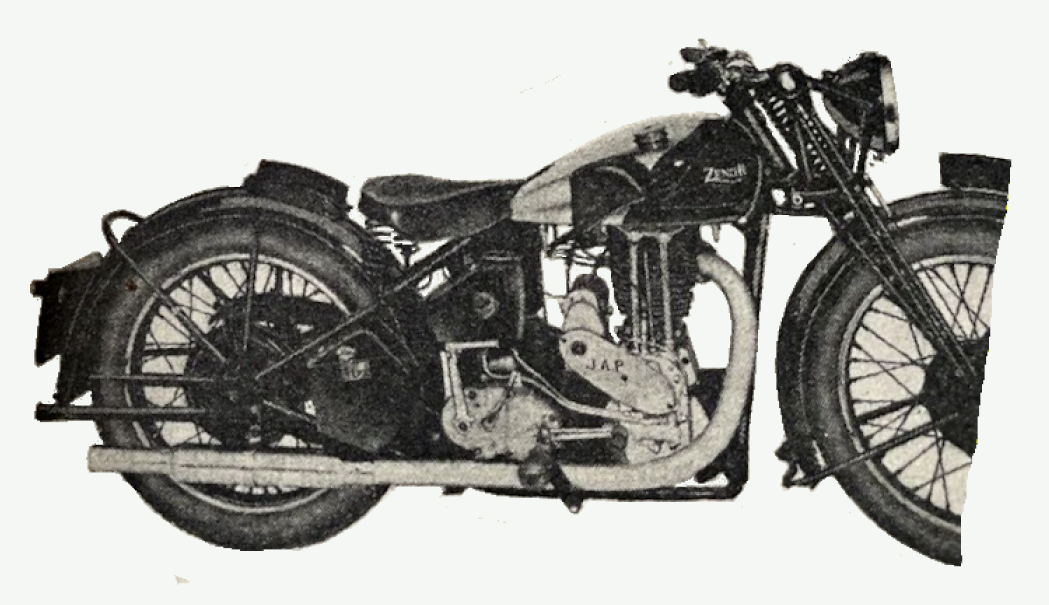

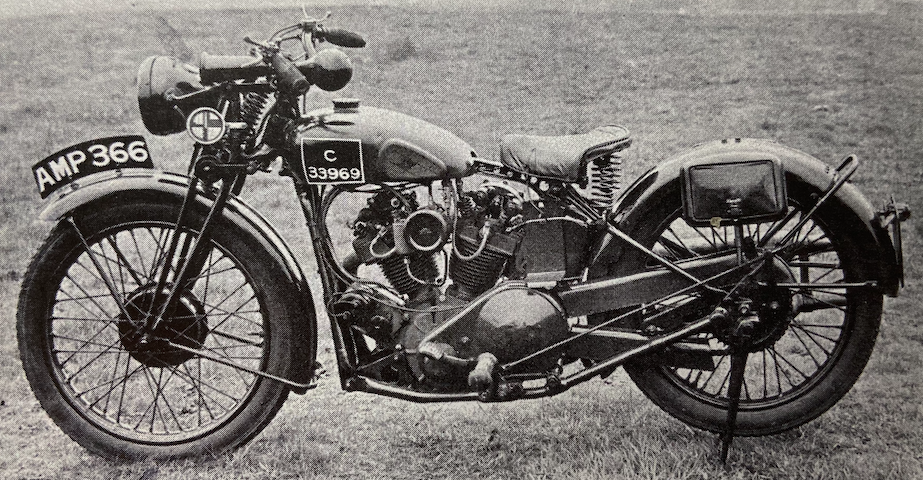

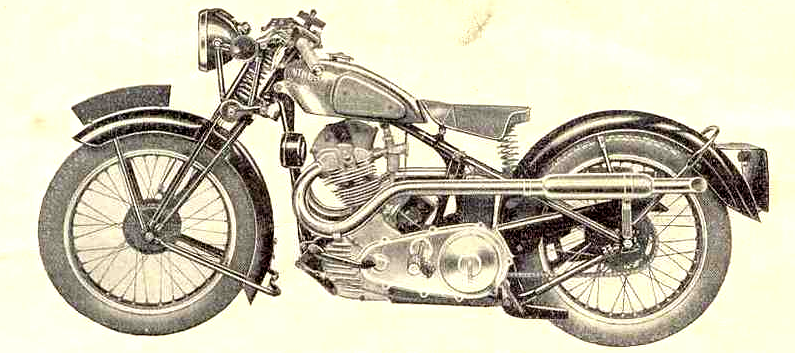

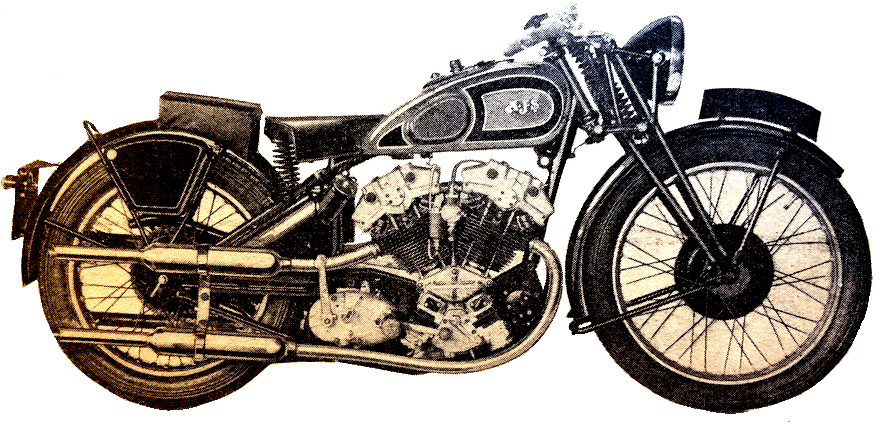

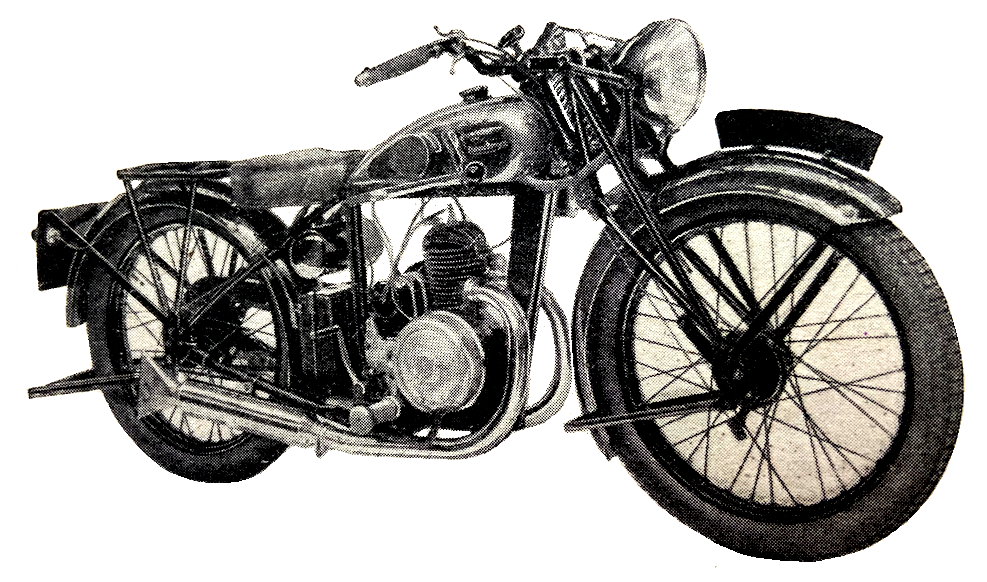

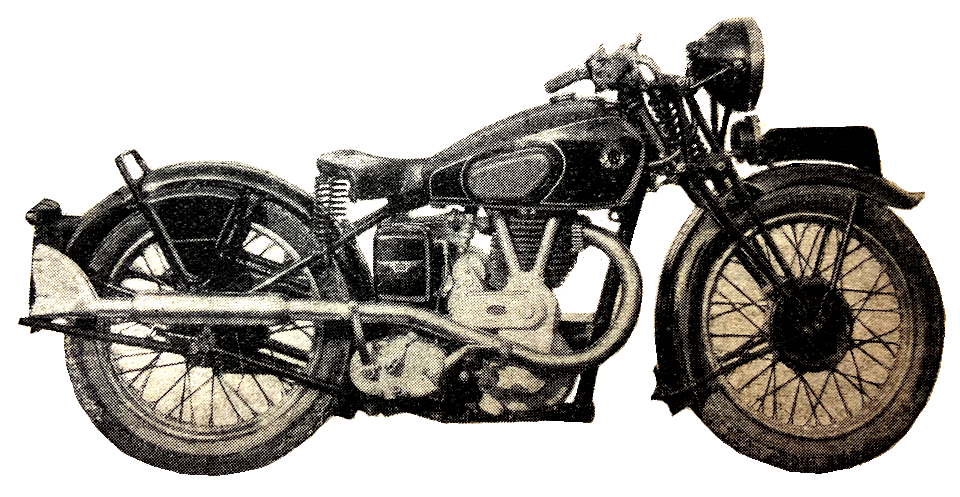

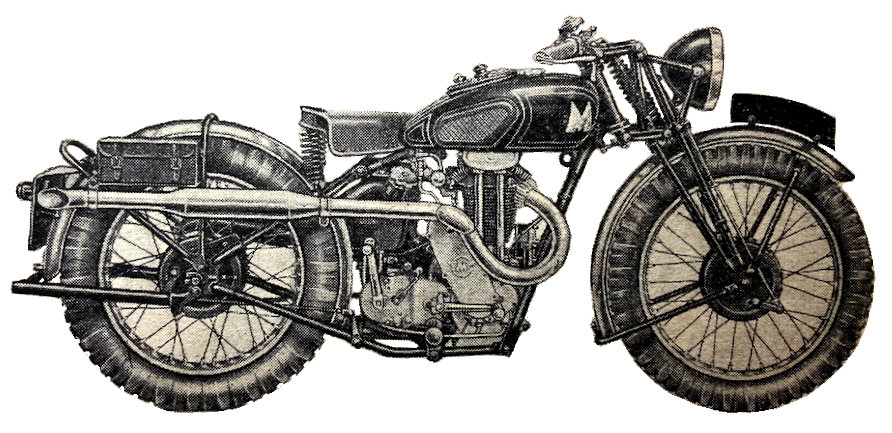

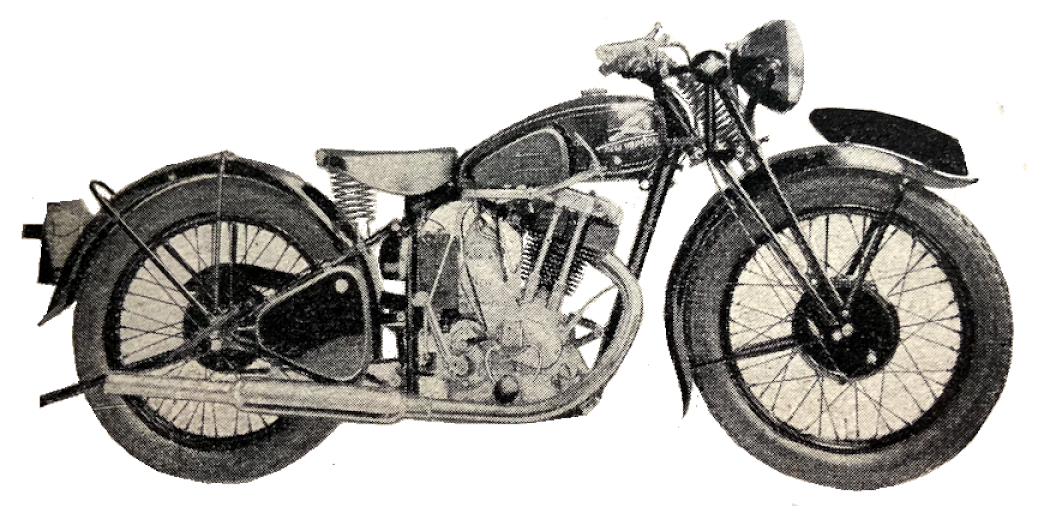

“A 498cc TT REPLICA JAP-engined machine is the outstanding model in the 1936 Zenith range. Known as the C5 Super, the new model has a very attractive specification and is designed generally to be a real ‘rider’s mount’. The massively built JAP engine has its cylinder deeply spigotted into the crank case. The valves are fully enclosed and lubricated; the rocker gear has automatic lubrication, and there is an adjustable oil by-pass to the cylinder itself. Dry-sump lubrication is employed, incorporating a fabric filter. The carburetter fitted is of the Amal down draught type. Ignition is by Miller Dyno-Mag. Transmission is through a Burman four-speed gear box with foot change. The primary chain is enclosed in an oil-bath case (with a detachable clutch dome), while the rear chain is automatically lubricated. The frame is of the full duplex-cradle type with Druid girder front forks with steering damper and shock absorbers. A low-lift rear spring-up stand is a useful refinement. A 26x3in tyre is fitted to the front wheel, and a 26×3.25in to the rear; a 7in front brake and an 8in rear brake are employed. Other detail points are the folding kick starter, two-lever petrol tap, three-gallon petrol tank, Dunlop saddle, rubber mounted handlebars, a quickly detachable portion to the rear mudguard, and a very complete took-kit. The finish is in black enamel, with the petrol tank chromium plated and with Zenith purple and black panels. The other machines in the range cater for widely differing tastes: the capacities of the machines range from 250cc to 1,100cc.”

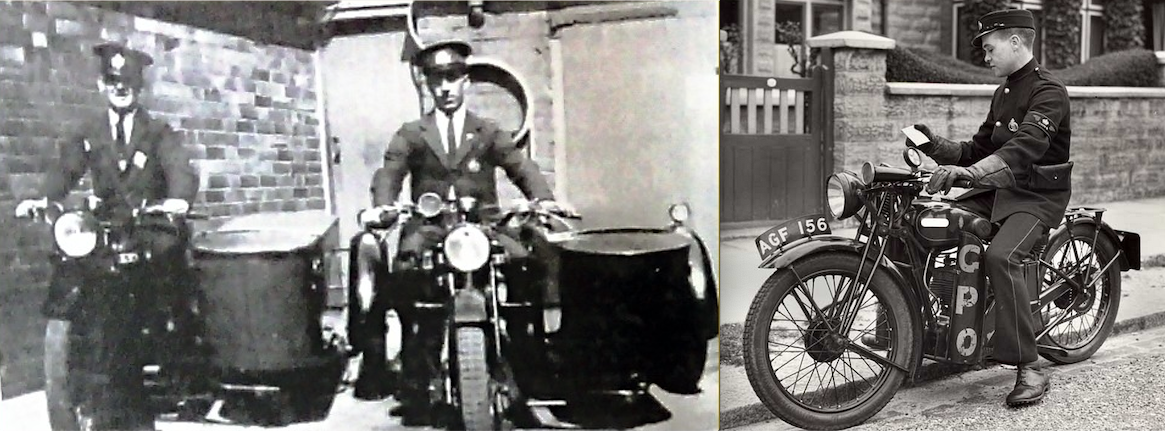

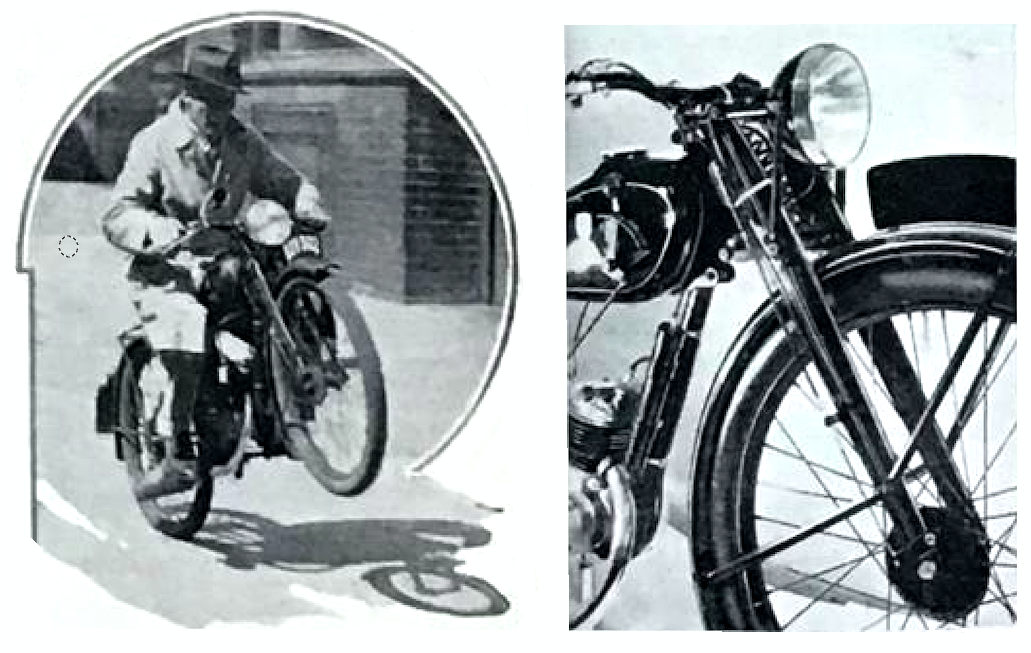

“HOW SIMPLE AND SAFE the modem motor cycle. is to ride has been proved up to the hilt—if additional proof were needed—by the announcement just made by the Post Office authorities regarding their motor cycle telegram service. In the past year 3,200,000 miles of city streets were covered by the messengers (all boys still in their teens!) without a serious casualty. About 200 machines have been in commission for 18 months, and each has had a yearly mileage of about 16,000. Where motor cycles have been used telegram deliveries have been twice as quick as formerly. Here are the views of a prominent Post Office official: “We are more than satisfied with the innovation, and we have reason to be proud of the boys who are in charge of the machines. The latter are all under 18, but they have proved skilful riders. Before the scheme was adopted some of us were rather nervous over the risk of accidents. The fear has proved to be groundless. There have naturally been some minor accidents in the heavy London traffic, but more often than not the fault been with the driver of some other vehicle. Certainly the motor cycles have turned out to be a successful means of telegram delivery. The idea that motor cycles are dangerous is exploded. Mechanical difficulties have been negligible, although each machine.is used by several boys. All the boys have been remarkably apt in mastering. the technicalities of the machines, in which they had a course of instruction. In time the service will be extended to cover the whole country.”

“AS WE CONFIDENTLY EXPECTED, the Postmaster-General’s experiment of mounting telegram delivery boys on motor cycles has proved a great success. The speed of telegram deliveries from the post offices concerned has more than doubled during the 18 months that motor cycles have been employed. And what of the boys themselves? No praise can be too high for these young riders—not one of them over 18 years of age. According to the official figures, the boys covered a total of 3,200,000 miles of busy streets during the past year—an average mileage of 16,000 for each rider—without a single serious casualty. When the scheme was first suggested, high officials in the Post Office were apprehensive about putting such young riders in charge of motor cycles. We are glad that the boys concerned have shown once and for all that not only is the youth of this country to be trusted on the roads, but also that the motor cycle is the safest and finest vehicle on which to gain experience.”

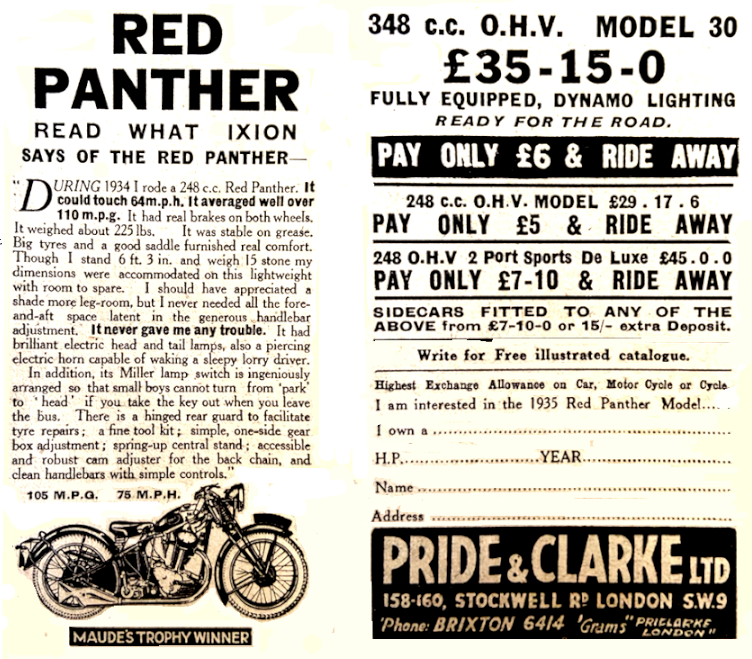

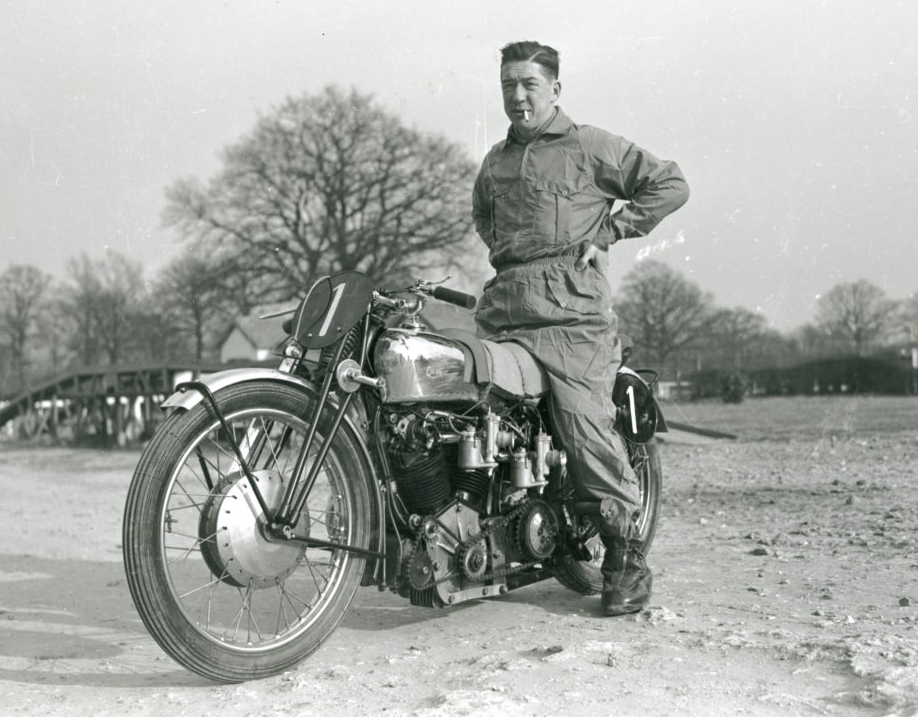

MOTORCYCLE SPORTING EVENTS at Easter included track racing, sprinting, grasstrack, speedway, trials, hillclimbing, sandracing and scrambles. Highlights included a sprint at Gatwick Racecourse in which Eric Fernihough and his blown 996cc BruffSup broke the 12sec barrier with an 11.72sec standing quarter.

“AA PATROLS IN THE past year covered, in the aggregate, more than 34,000,000 miles and rendered mechanical assistance on over half a million occasions.”

“SPEEDY SPEEDO. HIGHGATE motorist: ‘My speedometer was out of order.’ Policeman: ‘I agree. When the car was stationary the speedometer showed it was travelling at 11mph.'”

“WRONG-SIDE PARKING. ‘I am sorry to say there is no law against pulling up your vehicle and leaving it on the wrong side of the road. If there were, many accidents would be avoided.’—Mr Justice Humphreys.”

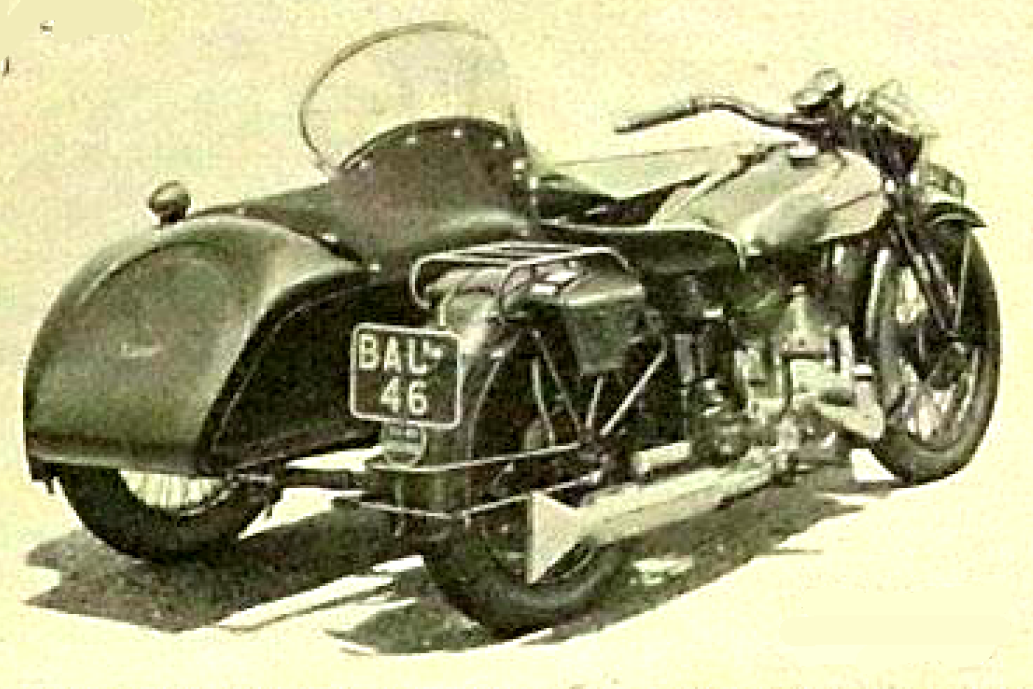

HARLEY DAVIDSON DEALER Earl Robinson crossed the USA from NY to LA on a Harley 45 flathead (that translates as s a 750cc sidevalve) in a record breaking 78hr 54min. Then he did it again on a combo with his wife Dot in 89hr 58min to set another record. They were both successful in long-distance trials; Dot later co-founded the Motor Maids of America.

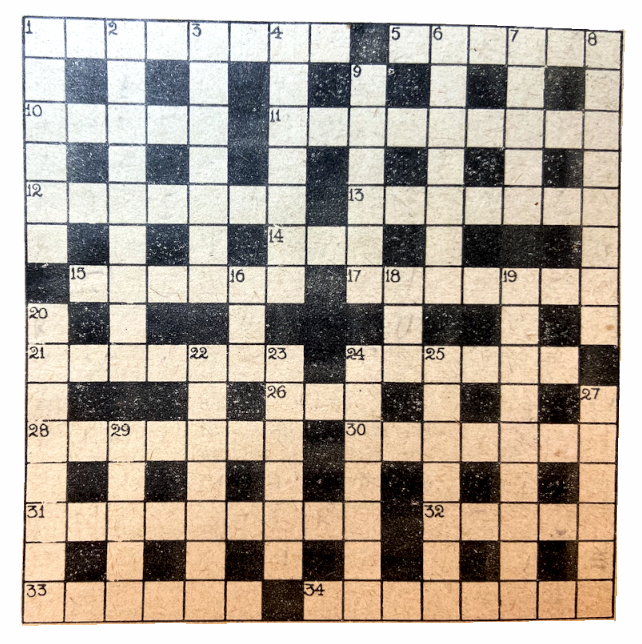

“TENS OF THOUSANDS OF READERS are no doubt on holiday at the present time. If you are one of them perhaps the following cross-word puzzle, which I am including with the Editor’s permission, will amuse you even as it has amused me. As you will find when you delve into it, the puzzle contains much that concerns motor cycling. Next week I will publish the solution so that you can check whether you have got all of it right. One thing I can promise you: it is not difficult—I managed to solve it myself!—Nitor [Nitor edited the ‘On the Four Winds’ page of the Blue ‘Un; I plan to try the crossword but you’re on your own with the solution—it was published in the issue dated 15 August which I don’t have, so best of luck—Ed.]

“WHILE ON THE SUBJECT of Post Offices, here is an out-of-the-ordinary adventure—quite true—which recently befell a reader, and which started in a small PO in East Sussex. When buying some stamps he overheard a gentleman making an enquiry re the licensing of his car. He had, apparently, forgotten to renew the licence, and the 14 days’ grace had also expired. Worse still, he had left his log book in his empty house in Dorset, 150 miles away! More or less as a joke, our reader offered to ride there, enter the house and find the log book, license the car at the local licensing office and return. The offer was accepted—and the whole thing was carried through successfully.”

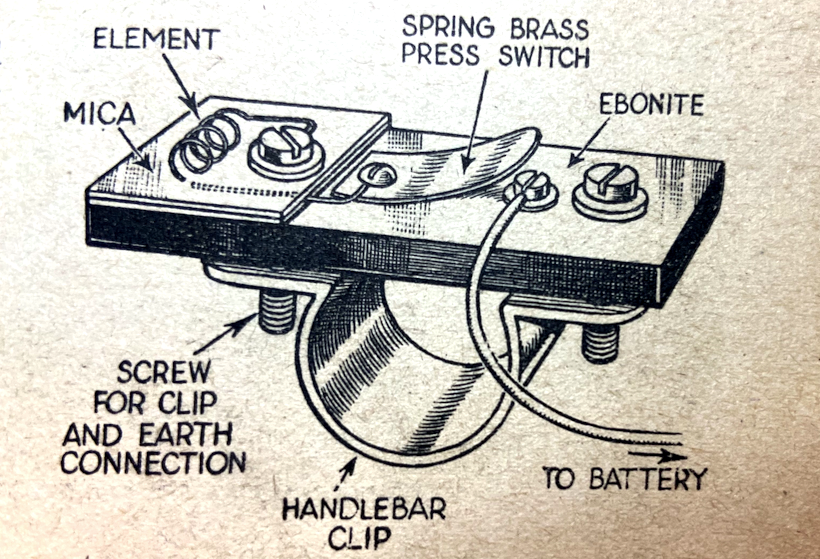

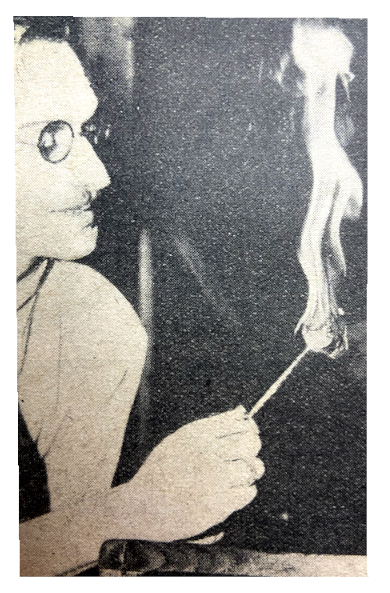

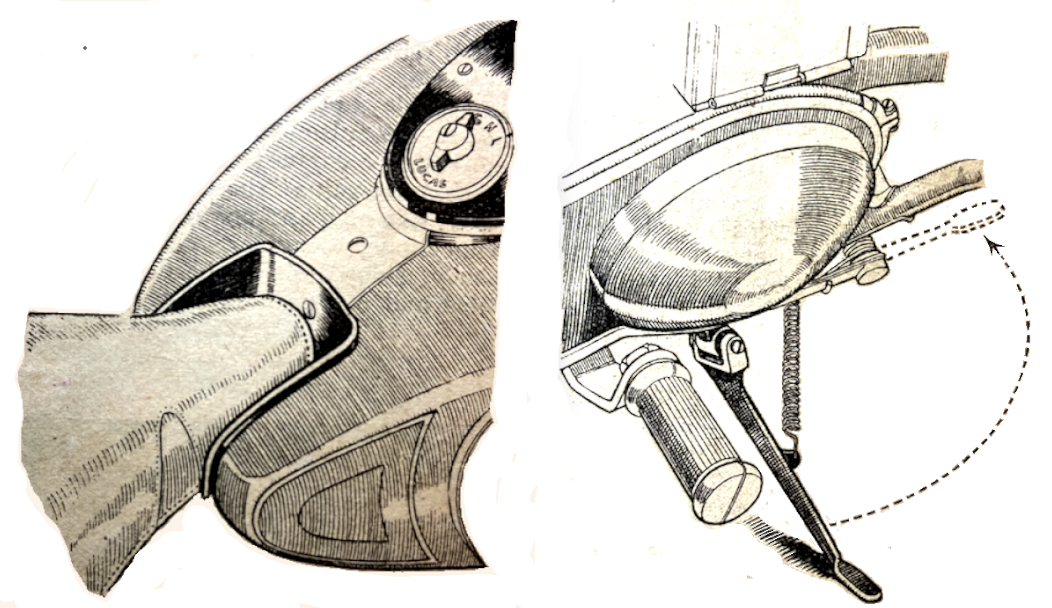

“AN ELECTRIC CIGARETTE-LIGHTER may be constructed quite simply from a few oddments, usually to be found in the motor cyclist’s ‘ junk-box’. The lighter in question is fitted to a BSA, and in action takes only 1½ amps out of the six-volt battery. The items required are, briefly: A piece of ebonite 2in long by 2in wide, an ordinary handlebar-clip, three cheese-headed bolts with nuts, a small piece of spring brass (for the press switch) and a wireless earthing stud, an element from an old electric fire (about 2in long and containing three small coils), and two pieces of mica for insulating the element. Examination of the sketch will make clear the construction of the gadget, which is quite simple to make.—’JHT Jnr’.”

“TOO SENSIBLE FOR WORDS. After 45mph limit signs had been erected in Honolulu, it was discovered that the maximum prescribed by law was only 35mph. It was too expensive to alter the signs, so the law was suitably amended.”

“PRETORIA (SOUTH AFRICA) HAS started a ‘fines-on-the-spot’ scheme for motoring offences. Using an unlicensed motor cycle costs only £1, according to the official ‘price list’.”

“BORINGS IN GERMANY resulted in 48,098,700 gallons of petroleum in the first half of 1935, compared with 29,217,100 gallons in the corresponding period a year previously.”

“TOLL TALE. SURPRISE has been caused by the news that a profit of £120,000 from Menai Bridge tolls may be handed to the Exchequer. In some quarters it is felt that any surplus should be devoted to reducing the tolls.”

“‘OF ALL INDICTMENTS of the high-compression single-cylinder motor cycle there can never have been one so forceful as the mere sight of these clubmen trying to get their engines started…’ Thus ran a pertinent comment in our review of The Motor Cycle Brooklands meeting. It so happened that the very morning this was published we received a letter from a reader condemning the BMCRC for not allowing the clubmen to have assistance in starting up. Fancy, it is actually considered desirable that motor cyclists—young and, presumably, hardy clubmen, not elderly men who have, perhaps, lost their early vigour—have help in starting their own motor cycles! Does not all this bring home to the whole motor cycle world, and through it to every manufacturer of motor cycles, that there is something seriously wrong with the general trend of modern design? The blame lies with our almost slavish adherence to the single-cylinder engine and the constant demand for more power per cc irrespective of the consequences. We have stressed over and over again this desire for easier starting, but still the tendency is to concentrate upon one type of motor cycle, which by its very nature must restrict the number of would-be devotees of the most economical motor vehicle that exists. Some definite evidence of designing and manufacturing enterprise in the motor cycle world would prove a tonic.”

“A TOME AT HOME? ‘The Highway Code is not a novel or a history book, but its influence—its practical influence—can be as considerable as almost any book that was ever written.’ —The Minister of Transport.”

“CONVERSATION PIECE. Motor cyclist giving evidence at Highgate: ‘He said to me: “Why doesn’t your machine go?” I said I didn’t know. He said: “Why don’t, you know?” I said I didn’t know, and he said he didn’t know either.'”

“OWN MEDICINE. Distinguished Ministry of Transport officials, says The Daily Telegraph, were to be seen recently picking their way across Whitehall Gardens through a sea of tar inadequately covered with stone chippings.”

“AN ‘ALL STATIONS’ CALL and a signal to the police wireless cars sent out when a vehicle is stolen costs anything from £15 to £20, according to a detective-sergeant giving evidence at Tower Bridge police court.”

“MOTOR CYCLES ARE ON the increase again—this is the interesting fact that emerges from the licensing return issued last week by the Ministry of Transport. The latest statistics show that at the end of February this year there were 30,000 more motor cycles registered than was the case last year. This might be explained as resulting from the dry weather but…the number of motor cyclists is definitely rising. In the recent past there has been a widespread desire to possess that key to the open road and freedom, the motor cycle, but thousands, because of lack of money, were forced to remain ‘motor cyclists on paper’. The tide has turned, and we believe that, excluding the so-called boom years, there will be more motor cyclists than ever on the roads this Easter. Only two things are needed; first, the boon of good weather, and, secondly, the realisation that an ounce of rare is worth a ton of regrets.”

Prepare for three doses of Ixion. Beautifully written, as always, but thought provoking too.

“I HOBNOBBED with a Yank the other day. Quaffing an Ovaltine in my den at Benzole Villa he picked up the current issue of the Blue ‘Un, and I saw him bristle suddenly, as a terrier who smells something fresh and catsome. (Should have said that the Yank is a big publicity man.) He began to hold forth on what an extraordinary country Britain is. ‘In America,’ he said, ‘motor cycles sell in quite microscopic numbers, considering the huge population and the general size of their motor industry; and sell only to cops and working men. But here,’—he almost stuttered as he drew my attention to the 40-odd pages of small ads. at the back of the issue—’you contrive to exalt motor cycling into a national sport, as proved by this constant interchange of machines and parts between individual enthusiasts, and you sell them to wealthy youngsters as freely as you sell them In factory apprentices.’ From that we wallowed in a lengthy argument as to why all phases of motoring are more individual and more sporting in England than in other countries, which emphasise the social and utilitarian aspects more than we do. I suppose the only answer is that we Britons are more individualistic. My Yankee friend admitted that he never dreams of driving himself when a chauffeur is available—a weakness which seldom assails us till we are seventy. It was also agreed that we Britons place a possibly exaggerated emphasis on sport of all sorts. We instanced two rich young men of our acquaintance—the one an American, who employs a chauffeur and seldom drives his own roadster; the other an Englishman, who will not allow anybody but himself either to drive or to adjust his Bentley.”

“ALTHOUGH I HAVE A PASSIONATE desire to see youthful male and female labour motorised, it is not due to self-interest. If a couple of million cheap lightweights could be sold in 1936 it would not benefit me personally a stiver. I am much more altruistic than I sound; and I dream of motorising the mass of labour because: (a) Motor cycling is a great asset to health. (b) Motor cycling is a great convenience. (c) Motor cycling makes a man concentrate, and his worries are driven out of his mind when he is in the saddle. (d) Motor cycling is highly educational, and teaches judgment and self-reliance. (e) Motor cycling facilitates far more enjoyable holidays than the railways or motor coaches. (f) Motor cycling introduces great variety into lives which’ without it may become monotonous.”

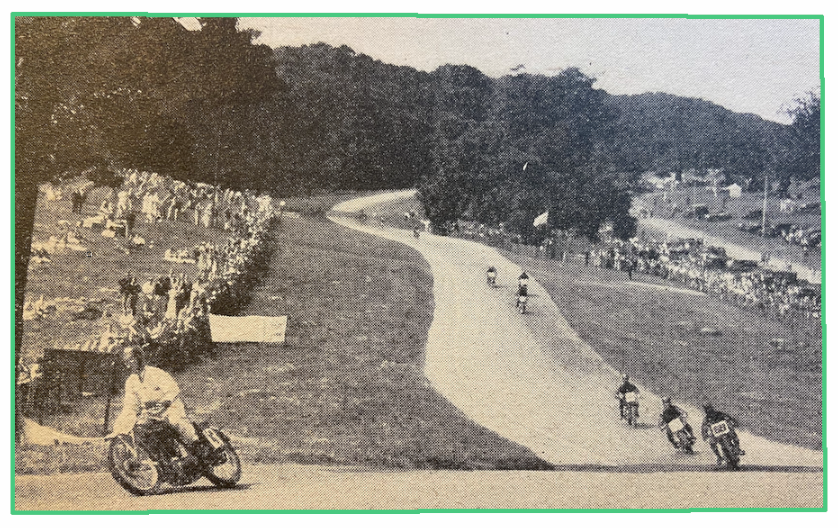

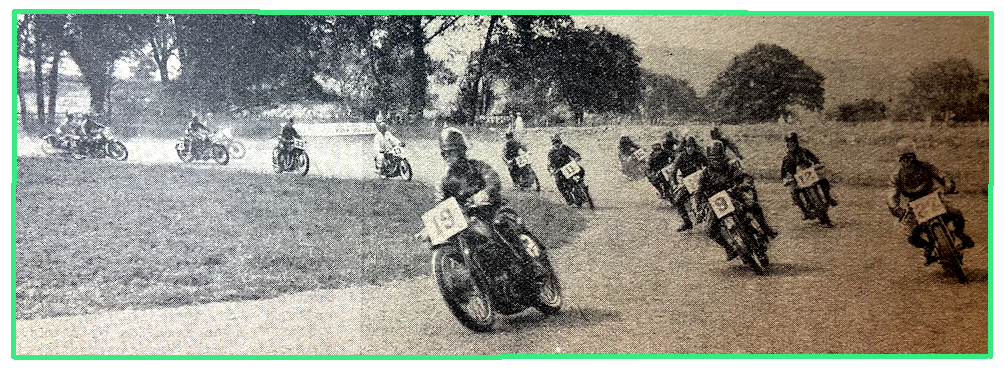

“DURING AUGUST BANK HOLIDAY the roads leading to the coast and to the many beauty spots were a-hum with happy, care-free motor cyclists. Adherents to the sporting side had their pick of many road races, trials and grass-track meetings organised by clubs up and down the country, and every event had its huge and enthusiastic following. Despite the busy condition of the roads riding was more than usually pleasant owing to the noticeable all-round improvement in road manners. Observation showed that motor cyclists were particularly praiseworthy in this respect, while drivers of other vehicles also appeared to have taken the injunctions of the High-way Code to heart.”

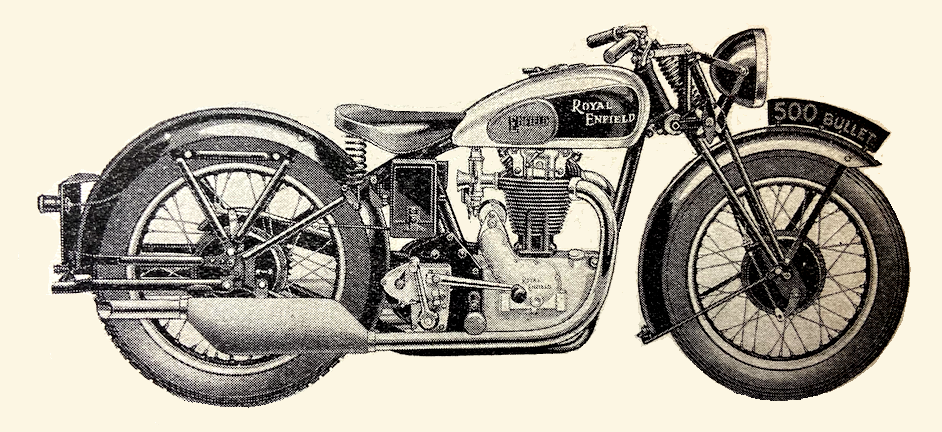

“THE MANAGING DIRECTOR of the Enfield firm has had a 98cc miniature built for his seven-year-old son—and I warrant the said son is the envy of small boys all over the Empire. The news set me thinking, for I often encounter a difficult problem which it might solve. A lad of licenseable age pesters his parents to equip him with a motor bike. His parents see me. They are moderately willing, so far as £sd goes, and admit that Jack has made himself fairly safe and knowledgeable on a push bike. But youth is naturally a little impetuous and rash; and the parents dread lest Jack should commit some blunder in his initial essays on our congested roads. Very probably there is no really quiet place where Jack may put in some hard riding practice. I usually solve their difficulties by driving Jack to some lonely place in a car and taking a baby two-stroke for him to learn on. But if I had a big agency I would coax Enfield’s to list the 98cc miniature as a production job; buy one, and instead the youth of my neighbourhood on cricket fields and other enclosures where no licences are necessary and where no age limit exists. What a happy afternoon any boys’ prep school could spend under such conditions!”

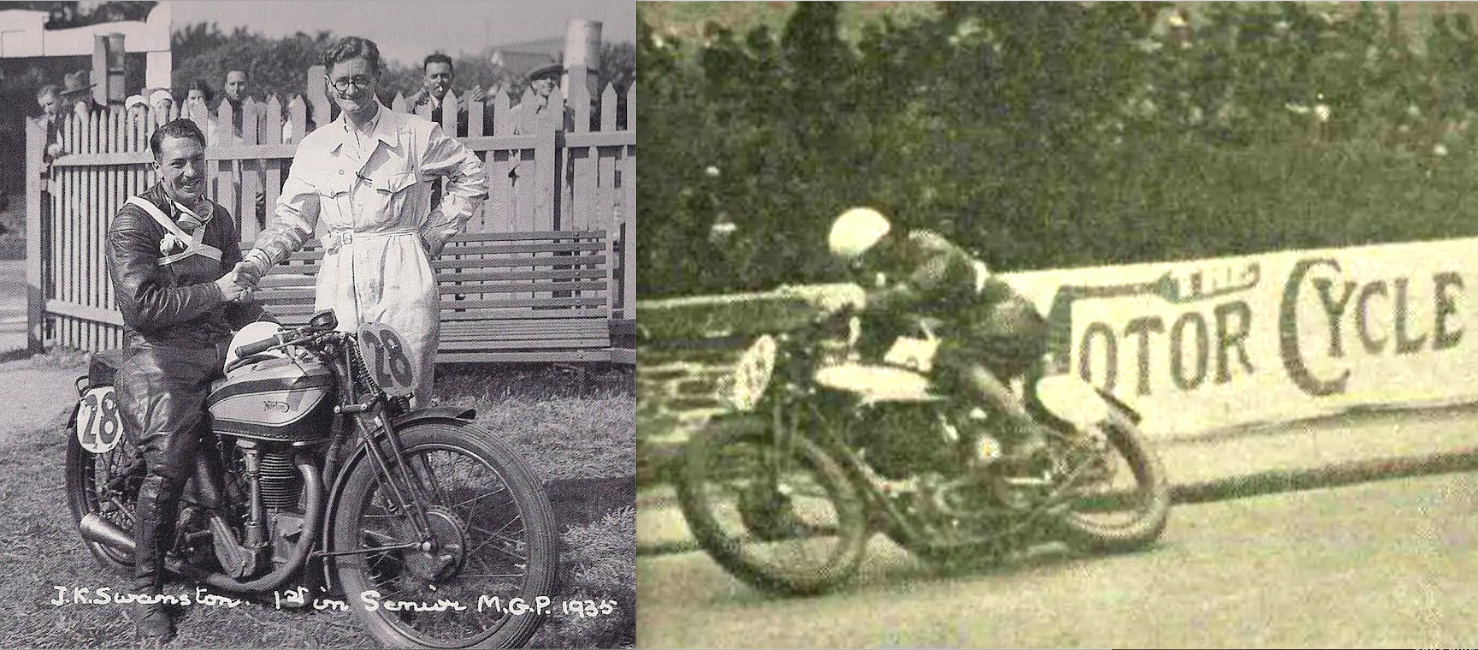

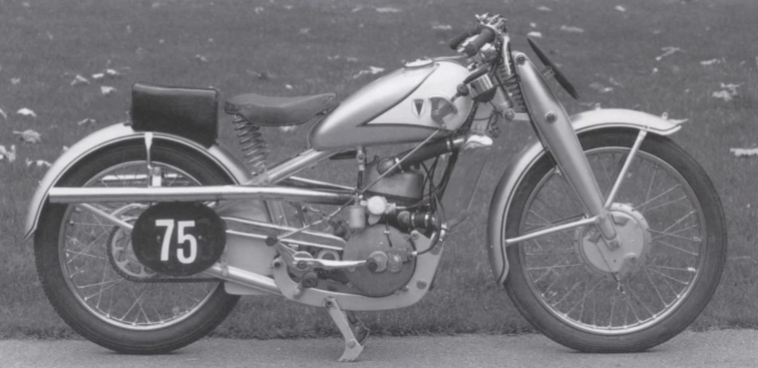

FOR THE FIRST time TT competitors were allowed to warm up their engines before the start; travelling marshals were appointed to patrol the course during races; pit crews were allowed to do more to help their riders; and the Manx flag was waved by the starter in place of the the Union flag. Understandably, after its traumatic 1934 experience, Husqvarna stayed away from the TT so Stanley Woods rode 250 and 500cc Moto Guzzis. The previous year Woods had made the fastest Senior lap and if he hadn’t run out of fuel would have won. In 1935 the ‘foreign menace’ was gathering momentum. Woods’ Senior Guzzi twin head effective rear suspension—the only Brits with rear suspension were Vincent-HRD and OEC. From Germany came 250 and 500 DKWs and NSUs which were known to be race winners on the Continent; they were joined by a brace of ohc unit-construction Jawas in the Junior and while the Czech contenders were untried no-one doubted their potential. Among the 107 entries were riders from Australia, Denmark, France, Italy, Spain and New Zealand. Woods broke the Senior lap record by more than 30sec during practice; his team-mate Omobono Tenni did likewise with the Lightweight lap record. But the Junior, as expected, was a repeat of the 1934 race with a Norton hat-trick courtesy of Jim Guthrie, Walter Rusk and ‘Crasher’ White—Norton’s fifth consecutive Junior victory. There were 19 finishers in the Junior; Norton, Velocette and AJS took the top 14 positions with Jock West’s NSU 15th, followed by three more Velos and an Excelsior. Two Jawas and two NSUs were among the ‘DNF’s. But, also as expected, Stanley Woods and his Guzzi took top honours in the Junior (setting another lap record in the process) to

record the first TT win by a foreign marque since the Indian tribe’s Senior hat-trick of 1911. He was chased home by Tyrell Smith and Ernie Nott of their Rudges and Ginger Wood on his New Imperial—three top TT riders on three top TT bikes. The message was clear: the TT was no longer a British benefit. A DKW and a Guzzi finished 7th and 8th—Omobone aboard the third Guzzi held second spot until lousy visibility caught him out and he crashed at Craig-ny-Baa on his fifth lap. Two DKWs failed to finish as, in the marque’s final TT appearance, did Freddie Clarke’s OEC. The big question was, could that man Stanley Woods and the 120° V-twin Guzzi do it again against the might of the Nortons? The poor weather that had dogged the Lightweight deteriorated to the point that, for the first time in TT history, the race had to be postponed. Many fans had to go home; so did some Senior competitors (including Noel Pope who had an

appointment at Brooklands…as we’ll see, it was a good call). But finally the mist on the Mountain cleared enough and the stage was set. At which point I’m handing over to TT Special editor Geoff Davison for an eye-witness account: “I can only describe the 1935 Senior as a terrific race. It was the fastest Senior up-to date, the course was lapped at over 86½mph, and it was won by the narrow margin of only four seconds. Jim Guthrie led on the first lap, with Walter Rusk on another Norton 27sec behind and Stanley on the Guzzi a second behind him. Then on the next lap the Irishman drew into second place, 47sec behind the Scots Norton rider. Jim increased his lead to 52sec on the third lap, but the difference was 42sec only on the fourth lap. The fifth lap saw Stanley creeping up, now only 29sec behind, and on the sixth lap 26sec. ‘Jim’s done it again,’ we said. ‘Stanley can’t catch him.’ Jim was No 1 in the race, by virtue of his last year’s win Stanley was No 30 [and thus started 15min later]. Jim came flying past the finish and everybody at the Grandstand rose to cheer him as winner of his fourth TT race in succession. When the lap times went up it was seen that Jim’s last lap had been covered in 26min 40sec, as against 26min 31sec for the lap before. It was, indeed, his slowest lap except the first, from a standing start, and the fourth, on which he re-filled. Still, he has plenty in hand, we said;

Stanley can’t do it. But Stanley, on the far side of the Island, was doing all he knew. Spectators reported that on this lap he was really in a hurry—not half he wasn’t! Flat out he went round that last lap, to do it in 26min 10sec, to break the lap record by nearly 4mph and to win the closest-ever TT race by four tiny seconds. And whilst he was doing it, Jim stood quietly at the pits, with anxious eyes on Stanley’s clock; knowing, of course, that he could have made his last 26min 40sec a 26min 30sec lap without any effort at all…So the Norton winning sequence was disturbed by an ex-member of their own team, a rider who had won five TTs on Norton and who that day scored his eighth TT success.” Everyone thought Norton had done it again until Woods flashed over the line and over the loudspeakers came the announcement: “This is the clerk of the course speaking, Stanley Woods is the winner—by four seconds!” So instead of their expected 1-2-3 Nortons ridden by Messrs Guthrie, Rusk and Duncan finished 2-3-4 to take the team prize—but they were followed home by Otto Steinbach and Ted Mellors aboard NSUs (once again a brace of Jawas failed to finish) and the TT would never be the same again although it was a good year for HRD-Vincent; having abandoned JAP in favour of the Phil Irving-designed own high-cam engine the Stevenage crew finished 7-9-11-12-13.

WOODS LATER DESCRIBED THE race in a feature for the Blue ‘Un: “In this Article, Describing His Tactics in the Most Thrilling Road Race of the 1935 Season, Stanley Woods Shows an Ability for Writing that is Second Only to His Skill as a Rider” “There has been so much written about my win in this year’s Senior TT that perhaps it will be of interest to many followers of the game to know the inside story of the race and of the events which led up to it and determined the tactics used by me. In the the first place it will be remembered that this year, previous to the TT races, I failed to finish every race in which I started on Moto-Guzzi machines. My retirement in each case was caused by a more or less serious engine failure—and every time something different! This state of affairs rather damped my hopes of success, but with three weeks to go before the start of TT practice, we set about modifying the parts which had so far given us trouble. In addition to addition to these modifications we reduced the power output by lowering the compression ratio quite a bit. The fact that we were ready for practice speaks volumes for the energy we expended. It soon became apparent to us that, excluding mechanical failure, we had little to fear in either class. My win in the Lightweight confirmed this, but upon examination of the engine after the race I realised that I should have to change my methods of driving if I wished to complete the course in the Senior. In the Lightweight race I drove the engine to peak revs (7,700rpm) in each gear, but seldom exceeded 7,300rpm in top, except on the second lap when I drove as hard as I could! Accordingly I began to work out how quickly Guthrie would go—and promptly slipped up very seriously! I forgot that in practice last year he had lapped in 27min 1sec, and that if conditions had been good in 1934, in all probability he would have gone round in about 26min 50sec—so I let myself be misled by his best practice time this year (speaking from memory, 27min 20sec). I expected an opening lap at about this speed (82.3mph) and decided that it would suit me nicely. Thus, I would save my machine and at the same time lull the opposition into a false sense of security, as during the last three years my tactics have been to establish a good lead as early as possible (when possible!) and then hold it. My idea was to keep somewhere near Guthrie on time until the last lap, and then take the lead with a final lap in about 26min 30sec. But, as is often the way, the best laid plans slip up. Came the great day, with both my private telephone stations and timing staff working perfectly. My pit man was drilled to perfection; he knew that I would fill up at the end of the third lap, and was prepared to give me half a gallop or so should I need it at the start of the last round—and was anxious to bluff the opposition into believing that I would definitely need it and so perhaps make my task a little easier. A final talk on the phone to my ‘back of the Island’ station at about 10.15am gave me the reassuring news that conditions were rapidly improving, and that as far a Ramsey there were only two slightly damp spots—bright news indeed after the previous three days’ conditions! A last word to the lads in charge of my ‘No 2’ station at Glencrutchery Road and I leave for the Paddock. The extra half hour’s wait, due to the postponement, throws an extra strain on all the riders, but I am not unduly nervous and the time soon passes. From the word ‘Go’ my bike runs perfectly, and in accordance with my plan I do not exceed 7,200rpm in the lower gears or 7,400rpm in top. With the exception of a severe skid at Greeba Castle, due to the frame dampers being a shade slack, I have an unexciting run until I reach any timing station, where I get the ‘thumbs down’ sign—meaning that I am a little behind Jimmie G. I am tempted to open up, but caution wins—or almost wins—and I let her go up to about 7,300rpm in the gears up the Mountain. However, I go gently down the gears and easy on the bends as she is a very different machine from my 250, and I have not ridden her at racing speeds since Wednesday week—and then only for two laps! The day is perfect, and conditions could not be better—just a few wisps of mist high up on the hillside before the Bungalow. I thank heaven that the ACU did postpone the race—what a difference from Wednesday! This is real racing. What a. joy to have a machine under one which is anxious to go faster than one thinks necessary! And so to the end of Lap 1. Through the pits so fast that I can only just pick out my pit as I flash past—but it is only necessary to locate it accurately for my filling-up stop, as I get all my information at my ‘No 2’ station several hundred yards below the pits. Here a shock awaits me, for ‘No 1′ has telephoned through the correct results for the first half-lap—’Second, 15 seconds behind.’ A nasty shock, but I must not panic. Down Bray it soaks in—15 seconds in half a lap! Then I remember those extra hundred revs up the Mountain and decide that that will hold Guthrie OK. On I go, keeping the revs down, but going a bit harder on the bends till I reach ‘No 1’ station again and get the times for the first lap—still second —that’s OK, but now I am 28 seconds down. I panic for a while and turn on the gas for a mile or so. It is surprising how much time one has for thinking when travelling round the Island at about 84mph, so Reason soon returns and I throttle back, but decide to lose nothing on riding. Up the Mountain once more and down again to Douglas. More bad news—a lap and a half done and and another nine seconds lost. A total of 37 seconds in arrears—this will not do, so reluctantly I decide that I must go faster. I decide on 7,400rpm in the gears and peak safety revs—7,700— in top.

The Guzzi seems to like it, and, of course, pulls the higher gears much better after revving up the extra bit in the lower ones. I reach ‘No 1’ again and find myself another 10 seconds down—47 seconds for two laps! I won’t know how much good my extra revs are doing until I pass the finish and get ‘No 1’ station’s report by ‘phone. Entering Ramsey I come up against my first snag—a couple of slower riders who hold me up for a few valuable seconds, which seem like minutes. The same trouble occurs again on the Mountain, but I soon get by and go on to finish the third lap. I accelerate hard from Governor’s while opening the tank caps and slow down early and brake to a gentle stop in exact position at my pit. In goes the petrol and oil, a heave, a few staggering steps, and the Guzzi bursts into life once more. A glance at ‘No 2’ station tells me that at last I’m holding Jimmie G—in fact, I have pulled back two seconds and am now only 45 seconds behind. Once more I tackle the ever-terrifying Bray, but this time with a lighter heart, and so on without incident to Sulby where I get further information from the timing staff. Curses! Another seven seconds down—a total of 52 seconds for three laps. I fume as I remember those baulks near Ramsey and on the Mountain, and I hope I shall meet no more. On to Ramsey—the Bungalow—Windy—the 33rd—concentrating on the exact line everywhere, and happy in the knowledge that I am taking each bend faster every lap. The Stands with their waving flags and cheering crowds, and—Cheers! my signal showing a gain of four seconds. Here comes Sulby—another six seconds saved, but still I am 40 seconds behind and with only three laps to go I reckon it out as I approach Sulby Bridge. I gained six seconds that last half-lap 12 seconds a lap and I need 14 to tie. Surely I can do it without over-driving—surely I can find those few seconds somewhere on the innumerable bends. I feel sure I can and decide to nurse my engine a little while longer. The Stands again. The strain of restraint is beginning to tell and I can hardly wait for my signal. My optimism is justified for I have pulled back another seven seconds. I start the sixth lap confident of victory, and perhaps for this reason I have my one and only super thrill of the race. Approaching ‘Handley’s Cottage’—a tricky left-right double bend between the 11th and 12th milestones—at about 107mph, I forget to shut off until some considerable distance past my usual braking point. I suddenly ‘wake up’ and indulge in some really hectic braking and scrape through at about 10mph faster than I’ve ever got through before! A very rude awakening, but a lesson to me. Sulby’s tale is not so good when I get there. I am still 29 seconds behind, but I decide to hold to my schedule and not use maximum revs unless I have to. Ramsey and the climb over Snaefell one more, my motor going better than ever. The spectators realise that I am still in the running and are cheering wildly. Craig-ny-Baa is a wildly waving mass of arms. A strange thrill runs through me to know that they are cheering my efforts, and showing the true sportsman’s appreciation of a race well run, whether the rider be first, second, or also ran. Glencrutchery Road, and a quick glance into my petrol tank to make sure that all is well. To stop means to lose the race, but better second place than ‘Stopped on the Mountain’ as in 1934! All is well! For the first time in the race I let her go to peak revs in third gear, only engaging top below the pits. There is my signal—second, 21 seconds behind—another eight seconds saved. That was at Sulby I reckon as I rocket down Bray Hill at almost peak revs in top—110mph. Another eight precious seconds saved by the end of that lap will bring Jimmie’s lead down to 13 seconds—and another lap to go at 8 seconds a half-lap makes 26 seconds—I’ll win by three seconds! These simple calculations have brought me to Braddan and then the devil ‘Doubt’ creeps in. Surely the Opposition—familiarly known as Joe Craig—will have signalled Jimmie to unleash another horse or so, for he cannot have failed to notice my progress. I’ll have to risk it and turn on those extra revs—no I won’t, I will, I won’t—I will—three seconds is too close a margin when dealing with a combination like Jimmie G and his Norton. So leaving Union Mills I turn it all on, and the way the Guzzi responds in third after peaking in second is a joy. I get into top before Glen Vine, but realise the extra speed at which I’m travelling and return to third for this tricky right-hand bend. Back into top once more I find the revolution counter showing 7,700rpm. By the foot of the hill before Crosby it shows 7,900—about 116mph. Up the hill through Crosby it falls back to 7,700. Down the hill to the Highlander I keep her throttled down to that speed—fear for the engine and of the road surface helping to restrain me. From now on I most be careful. I am tiring slightly and am not accustomed to the extra speed which I am using. I must watch my braking points very carefully and shut off just the correct amount earlier to allow for this extra speed. Thank goodness the brakes are standing up perfectly. From the Highlander to Ballacraine I run with some slight restraint on the revs, and then I begin to think once again of the wonderful record of Jimmie and his Norton. To blazes with restraint! I run up to 7,700rpm in the gears and let her go as high as the road will let her in top. After all, once during practice I let the practice machine go to 9,000-odd in second and nothing broke. Quite by accident, may I add! On up Glen Helen and Greg Willeys, screaming in second and third, and then down Cronk-y-Voddy, screaming in top towards the bend. Then up to 7,800rpm before I shut down. A light touch on the brakes—third gear is engaged and down to it once more. I ease in time for Handley’s Cottage this time, and then prepare for that wonderful drop down Begarrow to the ’13th’ milestone. Round that—too bumpy to think of the rev counter—just about on the grass for a few yards—must take it easy! More bends—more bumps—a short straight—Kirk Michael, Birkin’s Corner, Bishopscourt, Ballaugh, The Quarries, Sulby, and my last signal…What a signal! Instead of the expected 13 seconds I see ‘2nd, 26 seconds.’ I can hardly believe it. What has Guthrie had in reserve? I almost despair, but thinking to die game I crouch even lower on the tank and by the end of the straight see the needle touch 8,000—118mph! Ramsey and the Mountain—I most not lose a hundredth part of a second anywhere. My motor responds better than ever, and peaking on all gears I top the long climb at 7,500rpm in top. Round the bend by the telephone box I get on the grass again, but it is smooth and it is where I meant to go. All along the course little groups of people are shouting and waving. The Bungalow, Windy, 33rd, Keppel Gate and down to Craig-ny-Bea with its cheering mob at 120mph. On to Brandish with the engine revs mounting and higher, and then hard on with the brakes for Brandish. Peak in second, peak in third, up to top, cut her off, brake, third, second. Off again, only another couple of miles. Seconds to save, but I must be careful. The bends are slower from Hillberry, but so tricky. The cheering crowds tend to put me off—I must ignore them—not even a little smile—except perhaps one of sheer happiness after a splendid race, for after my last signal I do not think that I can possibly win. Signpost, Bedstead, The Nook, Governor’s, the finishing straight—the chequered flag…I shoot off down the road some hundreds of yards. My Italian friends come running after me and smother me in congratulatory embraces—for what? For a good second? For a stout effort? I don’t know! Suddenly, a voice says, ‘Good lad! You’ve done it by four seconds!’ That was the biggest thrill of my life!”

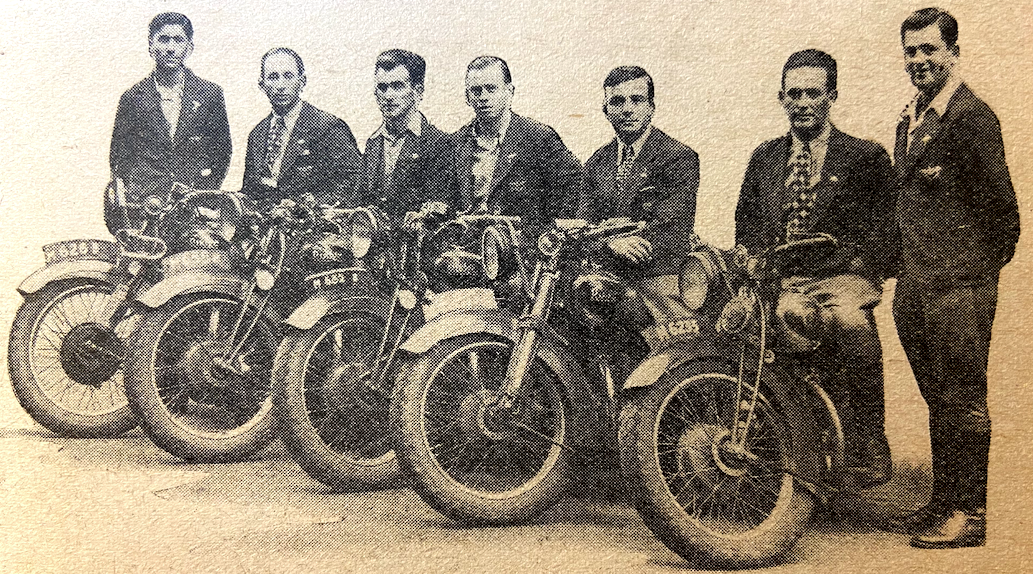

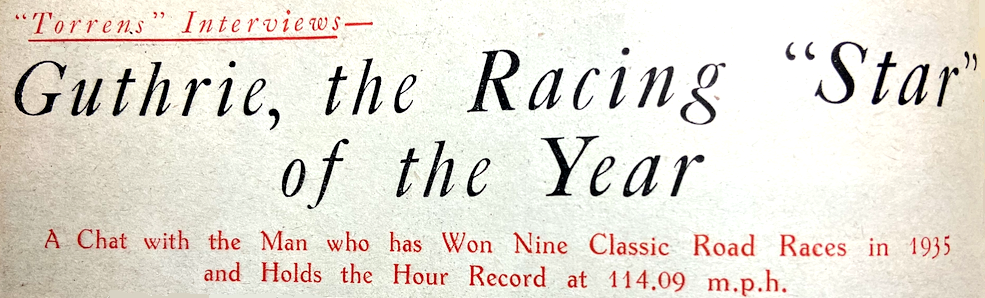

“HOPELESS—THAT IS HOW it seemed to Jimmy Guthrie. He wrote letter after letter, asking for he chance of riding in the TT, but not a solitary manufacturer displayed the slightest interest. This occurred little more than ten years ago, at a period when almost the entire industry races. was supporting competitions, and particularly the Tourist Trophy races. As I chatted with Jimmy, our thoughts—his and mine—turned to the present day. How much more difficult it is—indeed, next to impossible—for the budding star of to-day to break down the barriers and get his chance as one of a works’ team. As Jimmy said, there are so few makes to be approached. He himself had a hard enough task. Already he had done well in speed trials, sand events and hill-climbs. True it was in a small way, but he had been racing on his own account for five years and more. He started in 1920, following a spell in the Army as a Despatch Rider, and he had ridden in the Island in 1923 on a Matchless, more or less as a private owner. Having regard to his speed trial successes it might have been thought that some manufacturer would have sat up and taken notice of his possibilities as a racing man, particularly in view of the hold racing had upon the public. The way he got his chance is interesting. He was always a clever mechanic, and he succeeded tuning his AJS until it was moving really well. It was the Druridge Bay speed trials in 1926 that set him on the path to fame. The late Bert Le Vack, Brooklands idol and one of the most famous racing men of the day, was there; so was another well-known New Hudson rider, Ted Mundey, while looking on was Mr Price, who was managing director of the New Hudson company. Jimmy Guthrie had already approached Mr Price but without avail. The private owner proceed to wipe up Le Vack, winning both the 350cc and 500cc events—a lone man with no works’ backing against a powerful company and two of the best-known men in the racing world…Along rushed Mr Price and asked Jim whether he would ride for New Hudson. Jimmy would and did. ‘Things went very smoothly after that,’ says Jim. The following year he made his first pukka appearance in the Isle of Man, and if you look up the records of past races you will find J Guthrie (New Hudson) second in the Senior of 1927. He was a made man, and I believe I am correct in saying that from that day to this Jimmy Guthrie has only once finished a race without being either second or first. How many races this means in all goodness knows. In 1935 alone he was first in the Junior TT, second in the Senior TT—beaten by a mere four seconds—first in the 500cc North-West ‘200’, first in the 500cc Swiss Grand Prix, second to his team-mate, Rusk, in the 350cc Swiss Grand Prix, first in the 500cc Dutch TT, first in the 500cc German Grand Prix, first in the 500cc Belgian Grand Prix, first in the 500cc Grand Prix of Europe (Ulster) at 90.98mph, first in the 350 and 500cc classes of the Spanish TT, and, more recently, has raised the 500cc hour record—the ‘Classic Hour’—to 114.09mph. No ewer than nine firsts and two second places in famous international road races in a single year—what a record ! And if you talk to Jimmy you will be told that he owes it all Nortons: to the machines, to the directors, to Joe Craig, to the design staff and the Norton mechanics. To get him to talk about himself is next to impossible. There are one or two things I can tell you about him, though. Jim, as all are aware, is a Scot, and hails from Hawick, where he is in partnership with his brother in a garage business. They have a big machine shop; this is,Jim’s job, while his brother looks after the sales side. There is a lot of repair work, and that causes Guthrie’s difficulty—it is next to impossible for him to find time for any special training when he is at home and difficult to get away for the actual racing and practising periods. He has to rely chiefly upon work to keep him fit—work which often causes him to be still at it until eleven and twelve at night. The last year or two, however, he has really tried to make himself as fit as possible. He used to feel that it was impossible to compete with the younger lads in the Norton stable, such as Tim Hunt and Stanley Woods, and then he decided he would have a shot at it. Few people realise the fact, but Jimmy Guthrie is over 38 years of age. As I say, he decided to become as fit as he could. Once or twice a week he goes from Hawick to Edinburgh for 1½ hours’ muscle development exercises…While obviously the endeavour is to develop his wrists and arms, the important point is to develop his body as a whole, for in these days perfect fitness is essential to the road-racing man who is to hold his place at the top of the tree. What Jimmy finds really difficult is giving up smoking. He tried to do so last Christmas, ready for the TT in June, but never succeeded for more than a week or two, though he has managed to cut the number of cigarettes down to two or three a day. On the particular day I had this chat with him the racing season was a thing of the past, and the number he smoked— well, I didn’t count! In addition, Jimmy likes to have an hour or two each day on a motor cycle, but nowadays it is impossible to do any batting, he says, in view of traffic conditions and the speed of modern racing machines; therefore there is no chance of developing judgment at high speeds or indulging in true racing-type cornering. Since Guthrie is not a mere jockey but a real mechanic as well as brilliant rider I asked him how much work he does on his machines. In the Isle of Man, he said, all he any has to do is to ride, but on the Continent, if there is work to be done, he and Joe Craig do it. Fortunately, he added, there is seldom any need for anything except changing the carburetter jets to suit the the local fuel and conditions, and fitting new chains and tyres—fortunately, because there is very little time in view of the travelling from one race to the next and the need for getting in some practice on the fresh circuit. Since the Norton men do not necessarily ride the same machine each time I asked Jimmy about the alterations they have to make to the riding positions. I learned that one and the same position suits every member of the quartet, so there are no worries in this direction. From that I passed on to questions about Jim’s own riding position—there are few men who squash themselves so fiat along their tanks and. thus cut down wind resistance to the same degree. Had he ever tried lying down to it in front of a mirror? No, he hadn’t, and he mentioned that you cannot keep down to it when at speed in the same way that is possible when the machine is stationary. He added that one day he had to have three stitches in his chin—that was before his tank top was covered in rubber. ‘Even now you get some clouts,’ he said, feeling his nose tenderly as he did so. While on this question of lying down to it, he stressed again the need for fitness. ‘The young man who is naturally fit has a big advantage over the older hand,’ he added, ‘especially in a massed start, for he has started and is away yards—miles—before you are.’ Of course, we discussed riding methods.

You have or to go quickly in the TT right from the signal to start, said Jim. He used to have trouble in this direction—it took time before he became warmed up to it—but now, he says, the one thing he has to guard against is that he does not go too quickly—he has to hold himself in until he has settled down and feels he has got everything weighed up. He blames old age—or blesses it!—for teaching him that wild riding does not pay. Twice he came off this year, but in neither case was it wild riding. The first time was in the Leinster ‘200’—he had had no practice and came off on a patch of loose stones—and the other occasion was avoiding his team-mate, Walter Rusk, who had fallen at Aldergrove in the Grand Prix of Europe, that is, the Ulster Grand Prix. Nowadays, he says, one spends most of the TT practice period batting round the course trying to find the bumps and the way to miss them. On the bends, however, the line that can be taken is very limited, and often it is quite impossible to miss them. Within limits, Jim says, it is quicker to charge over the bumps than to take a bad line. This year he tried almost every conceivable course down Bray Hill. He even walked down it several times in order to spot the bumps and find a new route. It was hopeless, though, for he could not spot the bumps barring the obvious ones, and those he knew already! Finally, he gave up the task of finding a smooth route as being a bad job. Slow corners are the ones he does not like. On hair-pin bends, he says, he never seems very clever, and always feels that he is going slower than the others. Guthrie’s practice is to lighten down the steering damper until he feels that it is just gripping—so that with the front wheel off the ground the handlebars are stiffish to turn—just that and no more. All the damper does is to act as a steady; an important one, as will be realised when I mention that two years ago in the Island his damper broke and dropped him from third to fourth. I asked him whether he thinks it worth while adopting a touring riding position when one is actually rounding a corner in a race. His reply was: ‘If you are lying down to it and then start sitting up, you become all upset—you are in an unaccustomed position and therefore are better off if you keep as you were.’ He believes in lying down to it the whole time, even in cases where one is lucky enough to have a useful lead. Then the engine should be saved rather than the cramped limbs of the rider. In the TT, he said you have got to use all the power and speed that is available unless you have a good lead—as he thought he had when he came to the last lap of the Senior (which is especially interesting in View of Stanley Woods’ comments). In a massed-start race, however, you know exactly where you are; if you are in front, instead of sitting up to it, you save the engine by keeping in as high a gear as possible—you don’t rev the engine up so high in the gears as you would if pushed, and you ease the throttle back once the machine has got up to its speed But changing up sooner than you would do if pushed, he says, wastes a surprising lot of time even on a single lap. When changing up Jimmy always eases the clutch slightly and snaps the throttle closed. Coming into a bend he swishes in with the throttle shut and changes down with the clutch right out as the revs drop to a suitable speed for the engagement of the next lower gear. The clutch has to come right out in this case because the back wheel is driving the engine, and unless the clutch was out there would be clashing of the dog-clutches in spite of the closeness of the racing-type gear ratios. An interesting point Guthrie made is that when coming into a really slow corner you cannot go down to bottom gear straightaway—you have to engage each gear until such time as the rear wheel will take it without tending to lock, and therefore to skid. Changing down, even with a.very close-ratio gear box and considerable care, provides just about as much braking as the rear-tyre adhesion will stand. As regards the actual brakes, at least 90% of the work is borne by the front brake. It is practically impossible, he says, to lock the front wheel when braking in a straight line on a dry surface on, say, the Isle of Man course. Naturally, all braking has to be accomplished in a straight line, unless you misjudge a corner—then you certainly can’t use the front brake, but most tread very lightly on the rear one, and get out of the mess as best you can Those are Jimmy’s words, not mine, and are worth bearing in mind by every solo rider in the country. Finally, I popped question after question to him. Pit work: Jimmy told me that stopping dead at one’s pit without wasting a second is one of the most difficult things imaginable, and totally different from slowing down for a corner. ‘Have you ever experienced rolling with large section tyres?’ No he said; there was none at all with the 3.50in section rear tyres used on the 500cc Nortons. What of the future as regards racing design?’ Jimmy believes that the ‘multi’ must come…We parted, he to Scotland, and I to the office. Full marks to you, Jimmy;• you—quiet, modest you—and your famous Nortons have done more to uphold British prestige over the past two years than anyone else.”

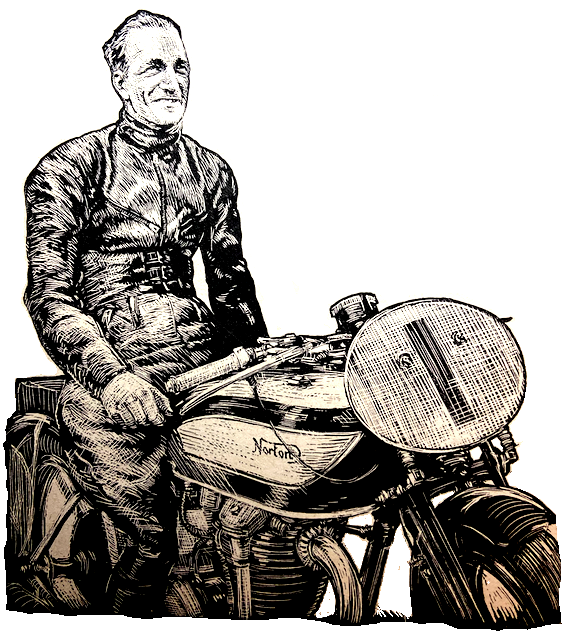

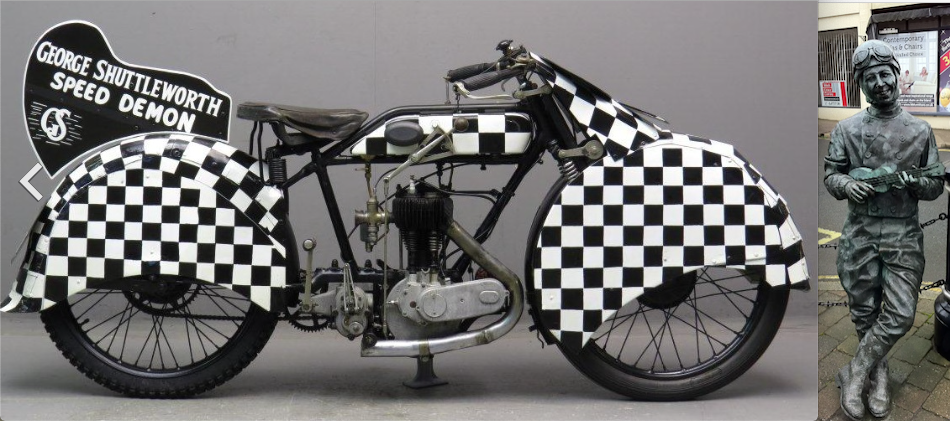

FORGET THE WILD ONE. Forget Easy Rider. No Limit, starring motorcycling ukulele maestro George Formby, and featuring footage from the 1935 TT, is the best motor cycle film ever made. Our George builds the Shuttleworth Snap, a modified Rainbow (actually a 1935 350 Ajay), takes to it to the Island, falls off Mona’s Queen, makes a record breaking practice lap when his throttle jams, throws the Snap off a cliff, wins a works ride on a Sprocket (actually an Ariel 350) nearly misses the start of the race, punches a bullying motor cycle racer in the snoot, pushes his bike over the line to win the race, wins the girl, wins a Sprocket agency and, of course, sings (all together now): “La la la la la-la going to the Teeee Teeee ra-ces”. You can hear the song at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eayllywNxUw and see highlights of the film at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwW0hElU6Kc. Eeeee turned out nice again!

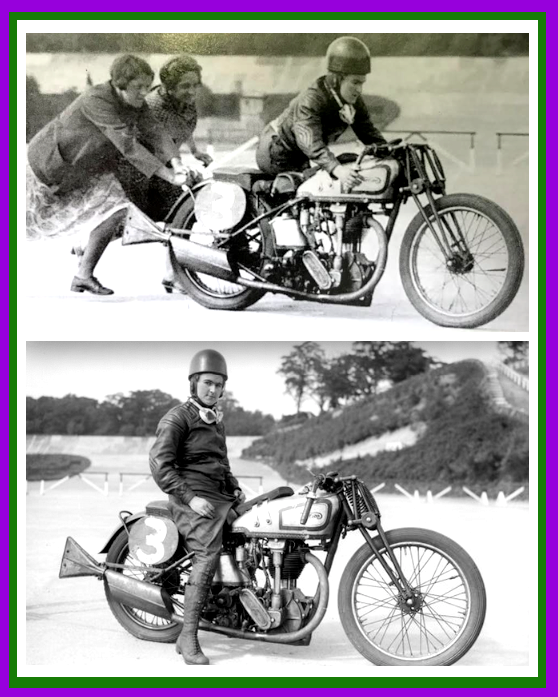

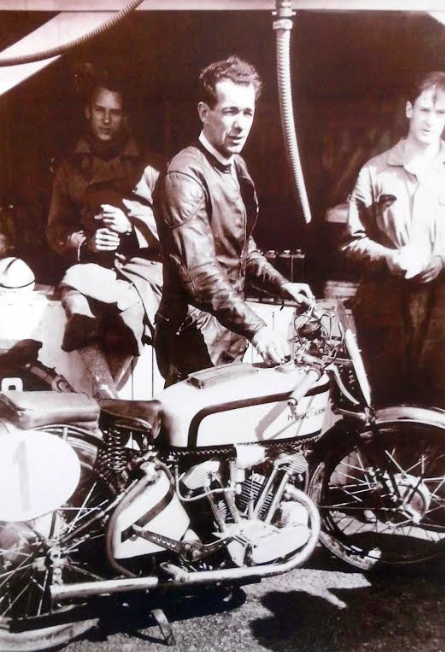

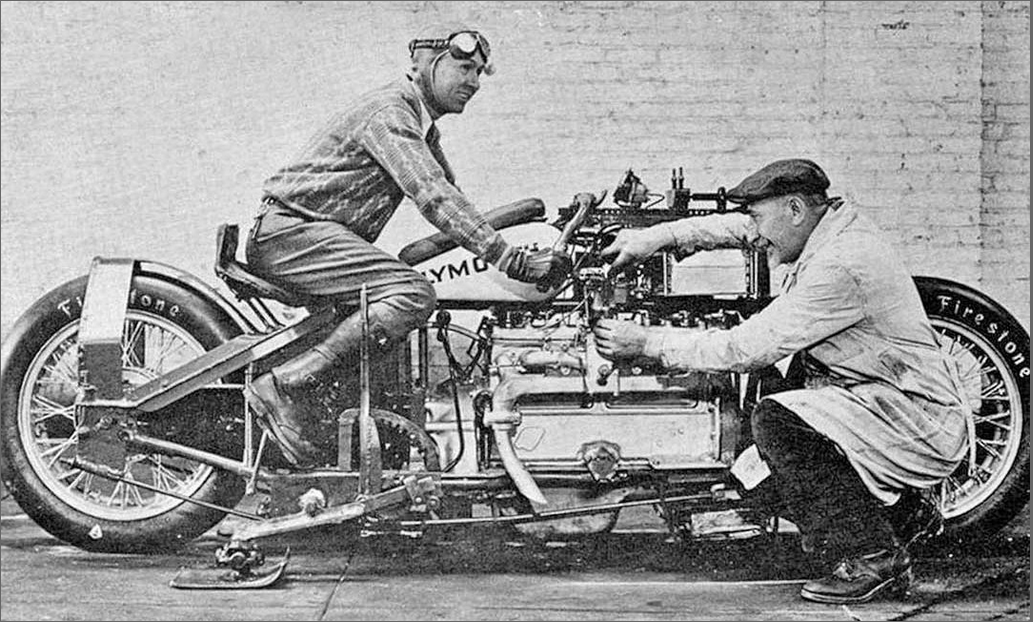

“NOEL POPE, A NOTED POET and novelist with a penchant for fast motor cycles, was entered for the Senior TT but when it was delayed by bad weather he left the island to keep an appointment at Brooklands. Pope had bought Ted Baragwanath’s supercharged 996cc JAP-engined Brough Superior outfit and set it up as a solo; he was after the Brooklands track record. And, as the Blue ‘Un reported: “After six years the Brooklands motor cycle lap record has been broken. A young racing man who only recently started riding very fast motor cycles has raised the speed to over two miles a minute—from 118.56mph, which was the record achieved by JS Wright on June 1st 1929, to 120.59mph. The feat is compensation for a disappointment. NB Pope, the man who now has the distinction of being the fastest Brooklands rider and the first to exceed 120mph for a lap, was to have competed in the Senior TT, but owing to the postponement he had to give up all thought of riding and return to the mainland. None but those who have an intimate knowledge of the track can realise what the achievement means. Brooklands is no billiards table. Even at touring speeds it is bumpy. Pope lapped in a series of breath-taking leaps. Thanks to the steering of his machine and his own grit this private owner set up a new Brooklands milestone.” He was awarded a BMCRC ‘Super Award’ for lapping at over 120mph. The same BMCRC meeting included s three-lap handicap: “Miss B Shilling on her self-tuned 490cc Norton ran through the field, and with one lap at 102.69mph provided a somewhat unexpected win. CR Bickell on the 499cc supercharged Ariel Four was second NB Pope (996cc Brough Superior), who covered his third lap at 116.38mph, third…The Brough Superior that EC Fernihough wheeled to the line for the second event, a two-lap handicap, looked very hush-hush in its sacking. Ferni was in his usual place at scratch and was giving 1min 32sec to the limit man, HR Nash (123cc New Imperial). Nash kept the lead until the end of the second lap, when he was passed by EC Garfield (996cc Brough Superior sc). Close behind Garfield was EG Bishop (496cc Exclesior sc) and the three crossed the line with only yards between them—really clever handicapping.”

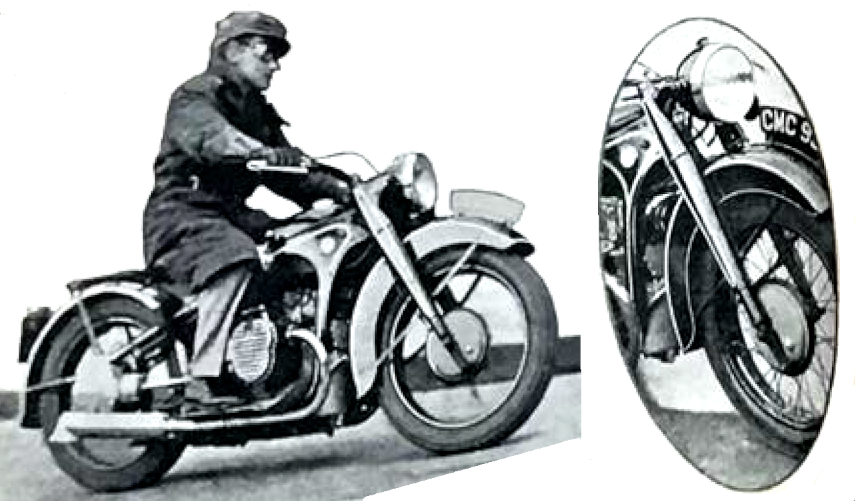

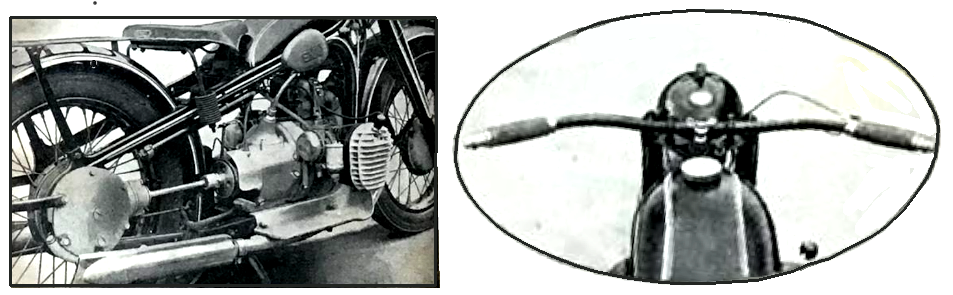

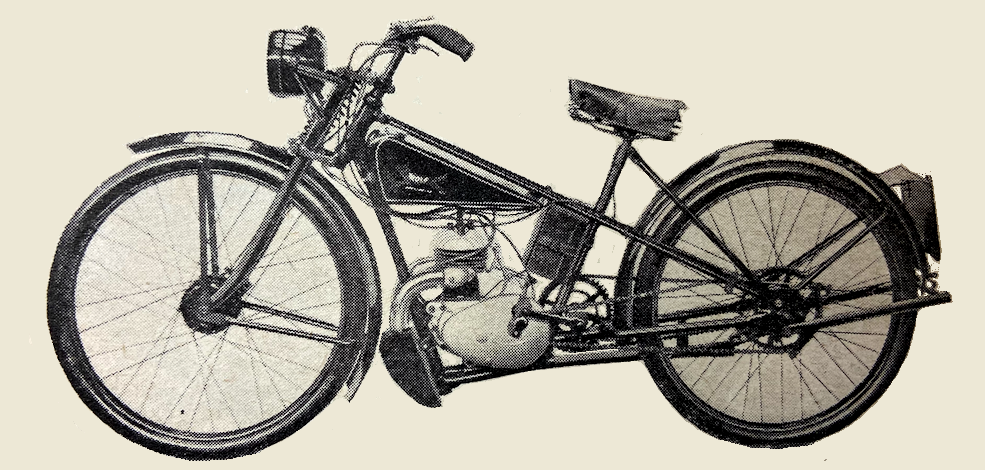

“A MACHINE WITH AN ENGINE of less than 100cc capacity is too small for serious motorcycling. This is the view held by many; indeed, it has been suggested more than once in these columns that such machines are only suitable for runabout work in flat districts. The 97.5cc DKW submitted to The Motor Cycle for test makes such opinions out of date. The writer would willingly set forth on this machine on a tour covering the length and breadth of Great Britain. And the tour would not be accomplished at a crawl, for the machine tested will keep up its 30 to 35mph with ease and thus maintain its position in any normal traffic stream. At first sight the DKW appears closely related to the continental velomoteur, chiefly because of its large wheels and small tyres. The minute engine is a two-stroke with a flat-topped piston is built in unit with a three-speed gearbox. Gears are employed for the primary drive, which is automatically lubricated by petroil from the engine, and since the magneto is incorporated with the flywheel, there is only one chain—the driving chain to the rear wheel. Lighting is of the direct type from coils in the flywheel, with a dry battery as a standby for parking purposes. Small internal expanding brakes (of 4in and 5½in diameter) are fitted in the front and rear wheels, which are shod with 26×2.25in tyres. The remaining features of the specification are a soft-topped saddle, a single-lever carburettor (without strangler), a special form of air cleaner on the carburettor air intake, pressed-steel, single compression spring type front forks and a central stand fitted with a spring which tends to flick the stand over dead-centre position when the machine is pulled backwards. Use of the stand is almost the easiest task imaginable since the machine in running trim was found to weigh only 119lb…Here is a machine with the performance of the popular type of small car plus the ability to climb hills at a reasonable speed. Britain has more than one engine of a similar size. At the moment they are lying more or less dormant. Perhaps the experiences we relate will arouse fresh interest in the small motor cycle…machines of this size, if they give satisfactory service, can form a valuable stepping-stone to larger and more expensive motor cycles.”

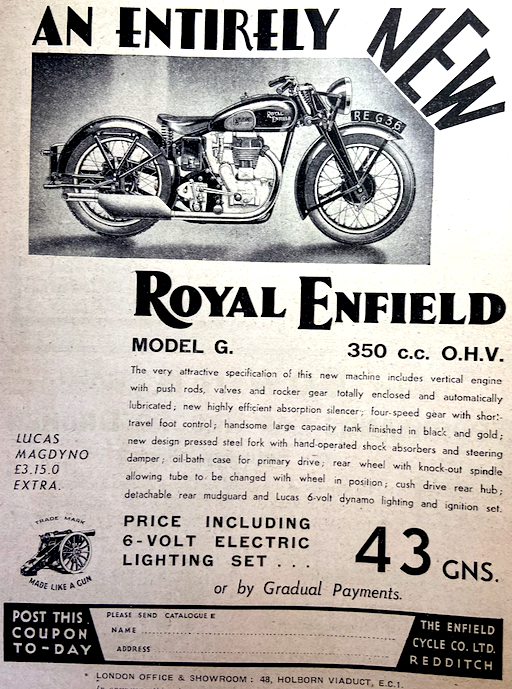

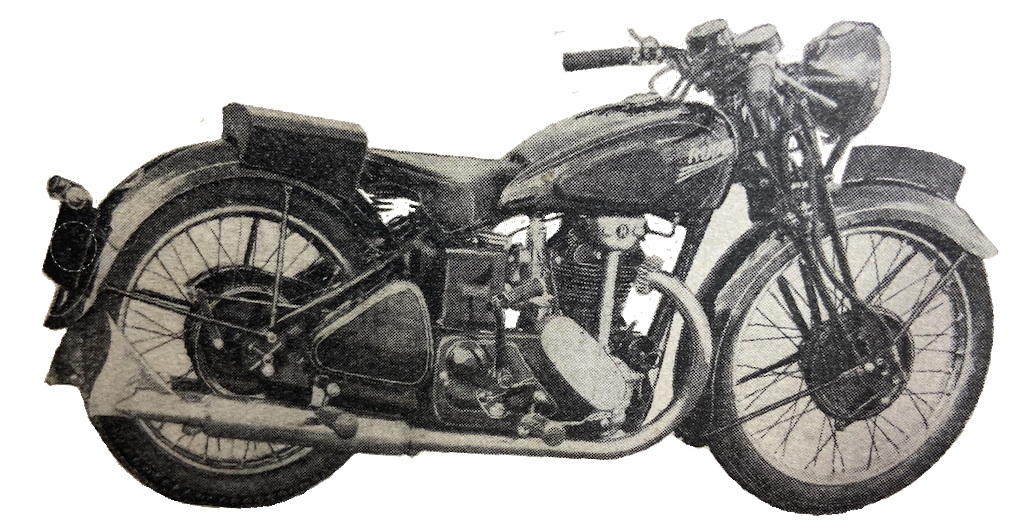

“WITH A DOZEN OR MORE 1936 programmes announced, it is interesting to pause for a moment to consider where the improvements lie. So far no startlingly novel machines have emerged from the secrecy of their chrysalids; instead there are whole ranges of standard-type mounts which display numerous new features, some of them of great utility. To the hard rider the features of, perhaps, greatest appeal are controlled battery charging and the widespread adoption of larger fuel tanks. It is probable that before long all new dynamo-equipped motor cycles will be fitted with this form of control which regulates the dynamo output according to the requirements of the battery. It will probably he the greatest boon since the standardisation of electrical equipment. For 1936 even small-capacity motor cycles will, in many cases, have tanks capable of holding three gallons of fuel. Often the cruising range on a tankful will be 250 or 300 miles. Ten years ago many a machine would only accommodate a gallon and a half, and the quantity that had to be purchased at each of the many stops for filling up was a single gallon! In addition, on machine after machine there are improvements in the riding position and modifications to ensure that routine adjustments, such as the valve clearances, can be made easily and quickly. A number of 1936 motor cycles incorporate some form of motif. Care, too, has been taken to ensure graceful lines. Particularly is this the case with the new and larger fuel tanks…the outstanding feature of the new models is the care and attention that have been lavished on them to make them more ‘rideable’—to make them ‘motor cycles for motor cyclists’.”

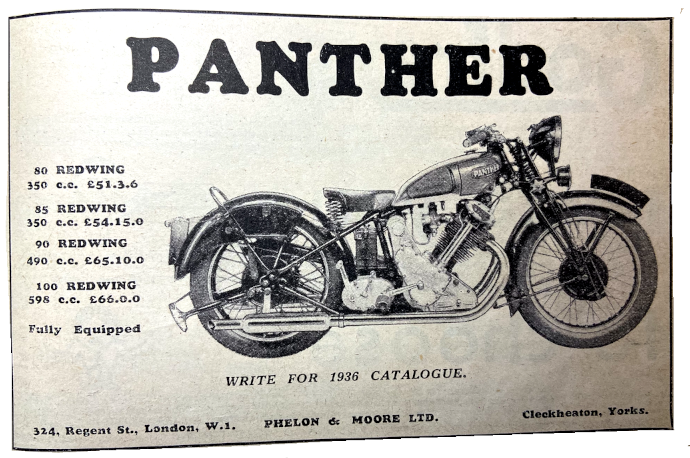

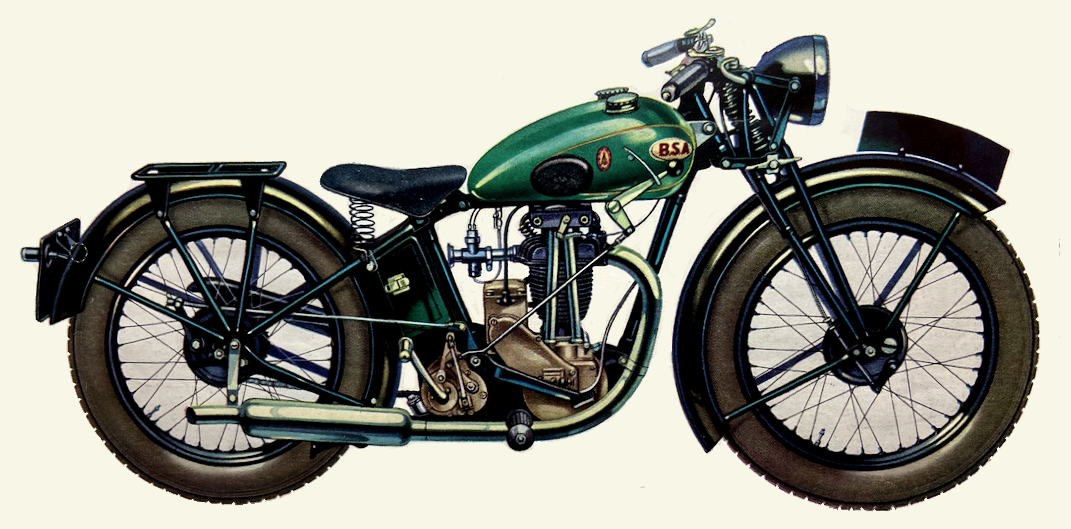

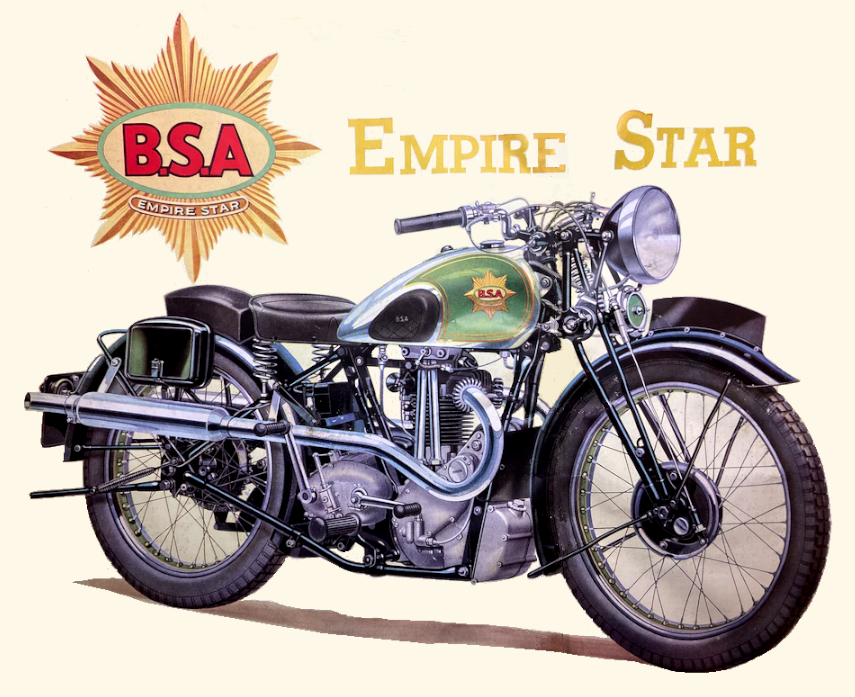

KING GEORGE V’S SILVER Jubilee led to countless press reviews of his 25-year reign. The Blue ’Un’s contribution was a review of the 1910 Olympia show, with a reassuring list of marques that had exhibited there and were still in business. They included: AJS (albeit under Matchless ownership), Ariel, BSA, Calthorpe, Douglas, Excelsior, FN, James, JAP, Matchless, Montgomery, New Hudson, Norton, OK, Panther, Royal Enfield, Rudge, Scott, Triumph and Zenith.

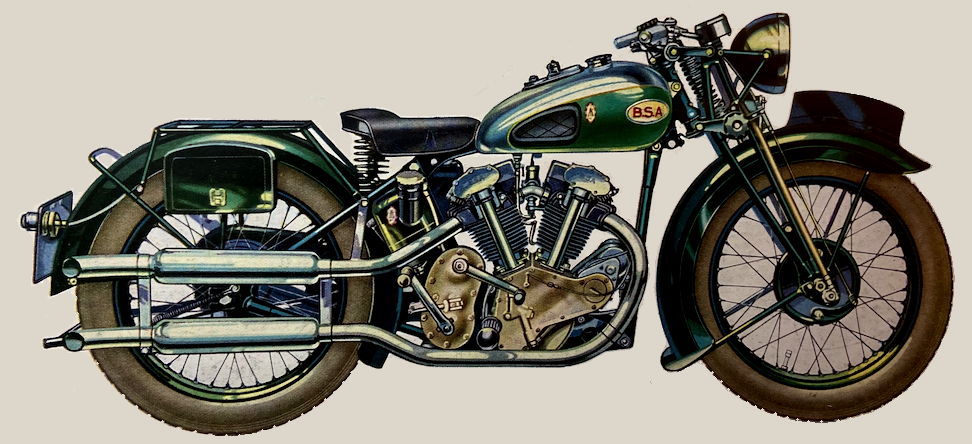

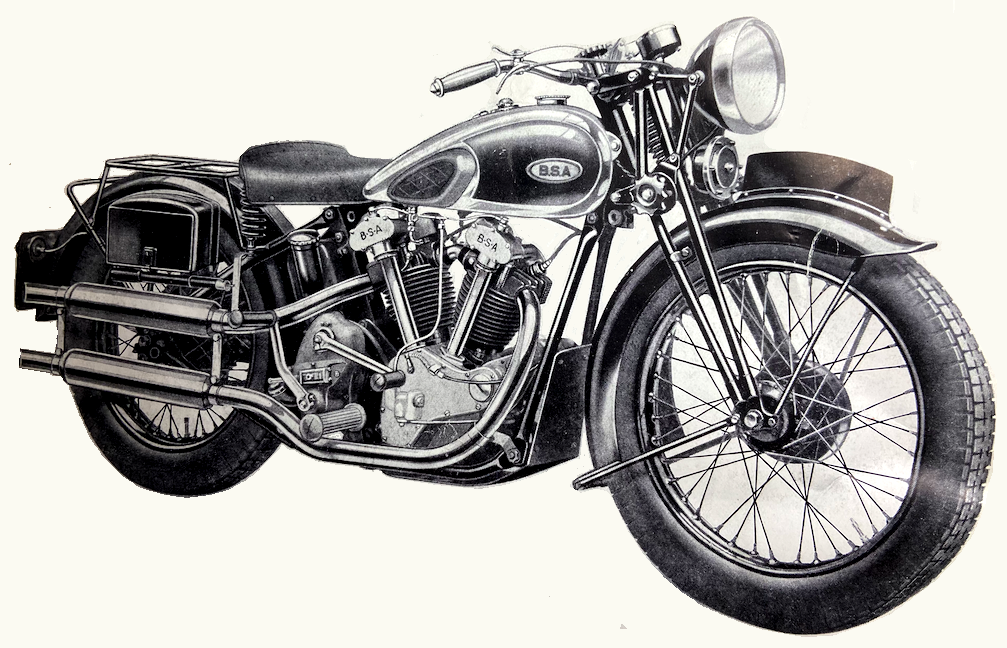

BSA MARKED THE Silver Jubilee with the launch of the Empire Star.

“MIGHT HAVE GONE WEST: A man was fined £2 at East Ham for smoking while driving a petrol-tanker lorry.”

PORTIA UP TO DATE: Summoned at Plymouth for disobeying a police signal, a woman motorist asserted that she hadn’t seen the signal, and, therefore, she couldn’t have disobeyed it! Fined an illogical 5s with 5s costs.”

“PARLIAMENT DISCUSSES ‘RIBBONS: In answer to a question in the House of Commons last week regarding ‘ribbon building’, the Prime Minister said that a Bill dealing with the matter ‘will be introduced as quickly as possible.'”

“HEN-PECKED?: A Parisian cyclist who sued the owner of a hen which swerved under his front wheel and upset him failed in his action. The Court maintained that the cyclist ‘tried to pass a hen that was keeping on the correct side.'”

“TRIUMPH OF DIGNITY: A Marylebone Police Court, during a pedestrian crossing case, a motorist made the novel plea that he was anxious not to imperil his new £1,000 car by a possible skid, so he hooted instead of stopping. Stranger still, the summons was dismissed!”

“BEACONSCIENCE: The Borough Treasurer of Kingston recently acknowledge the receipt of 5s.3d as ‘conscience money’ for the breakage of a Belisha beacon.” [Younger readers might care to flick back to 1934 to discover the source of their alliterative name; sub-editors will recognise the inclusion of a story as an excuse for a headline. All subs enjoy portmanteau words, and how often do you get the chance combine ‘beacon’ with ‘conscience’?—Ed.]

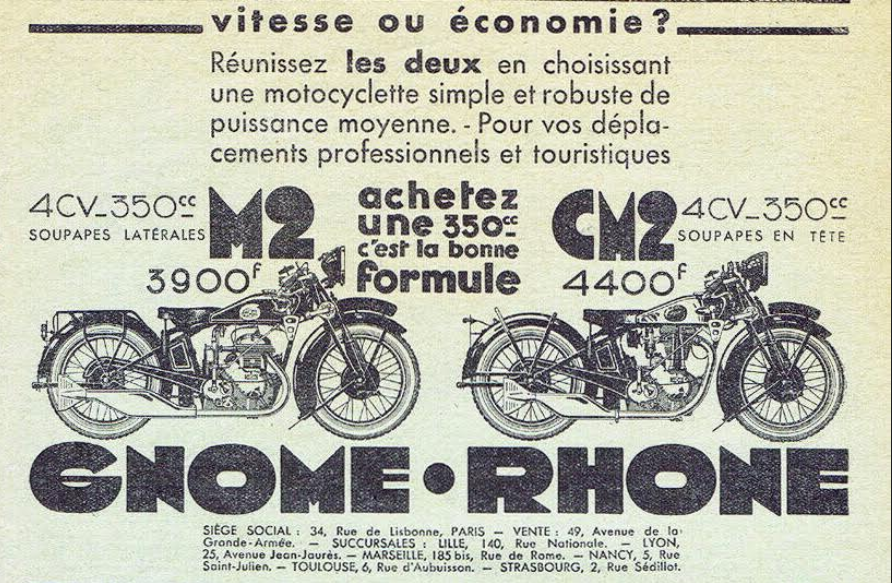

THERE WERE 48 MARQUES at the Milan show exhibiting 227 models; the major trend noted by tye B;ue ‘Uns correspondent was a move from 175s to 250s. There was no Paris Salon; the French industry concentrated on conventional 250s and 500s, as well as swarms of velomoteurs. In Germany the motor cycle industry, like the rest of the country, had fallen under strict government control, with various firms concentrating on specific classes—11 marques covered everything from two-stroke tiddlers to the big BMW and Zundapp flat twins.

ITALY AND GERMANY declared all motorcycles free of roadtax – and Italian motorcyclists wouldn’t even need driving licences.

THE JAPANESE GOVERNMENT was alsotaking an interest on motor cycles. The Japanese Automobile Manufacturing Law excluded foreign companies and foreign capital. The government said: “The motor vehicle industry is of major importance both for industry and national defence. Entrusting this industry to the control of foreigners is unthinkable.” Tohatsu was nominated as the sole manufacturer of small petrol engines to the Japanese military and developed a range of rotary-valved two-strokes ranging from 48-248cc. Rukuo began production of Harleys under licence for supply to the Japanese military.

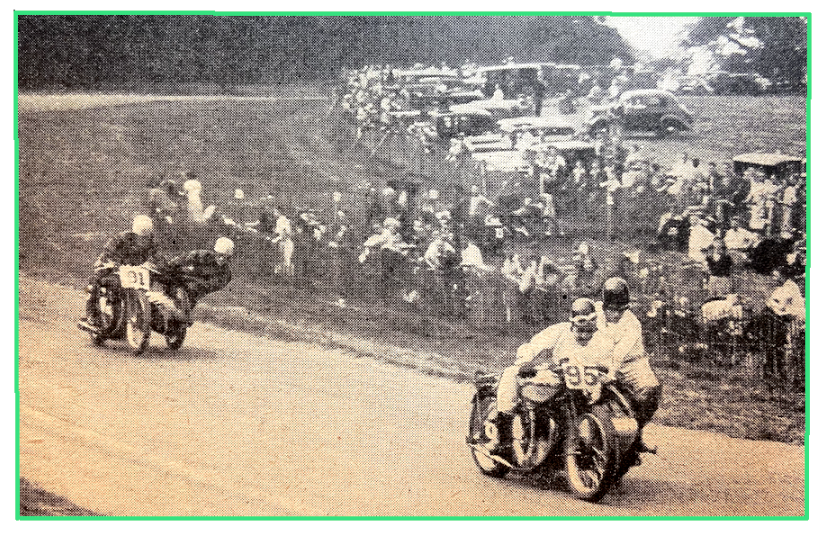

“THE HOPES OF THE DERBY Club officials, so far as the weather was concerned, were amply fulfilled on [August] Bank Holiday Monday. A brilliant sun was tempered by a light breeze, and conditions were ideal for racing. Donington Park looked lovely on this bright summer day, but, at first, there was a quietness about the place that seemed a little unusual. The crowd was only a thin one when the racing started, but hopes were held of a bigger muster as the day wore on. The finishing line is now graced with a beautiful Belisha beacon, but few pedestrians availed themselves of the crossing! A fine entry was received for the first event—a race for novices—and it was run off in two heats, each over five laps. The first heat was well contested, with HL Brooke (499cc Rudge) in the lead throughout, and he was never seriously challenged. However, there was a fine scrap all the way for second place, between SW Cooper (496cc Sunbeam) and WG Wright (348cc Velocette). Wright wrested the ‘lead’ from Cooper on the third lap, but Cooper was not to be denied, and passed his rival in a fine effort on the penultimate lap, and was not over-taken again. In the second heat, nobody could come near AJ Wellsted (493cc Excelsior). This rider established a wonderful lead on the first lap and was ‘miles’ ahead at the end of the race. The second man, WA Jordan (348cc Norton), occupied a gap in the ‘field’, being a long way behind Wellsted, but a long way in front of HS Green (497cc Ariel). Green, however, did not retain his position, for GA Chamberlain (348cc Norton) went ahead of him towards the end. As appeared obvious, Wellsted proved the winner of the race, with two heat-heat men, Brooke and Cooper qualifying for the places..Result, Novices’ Race: 1, AJ Wellsted

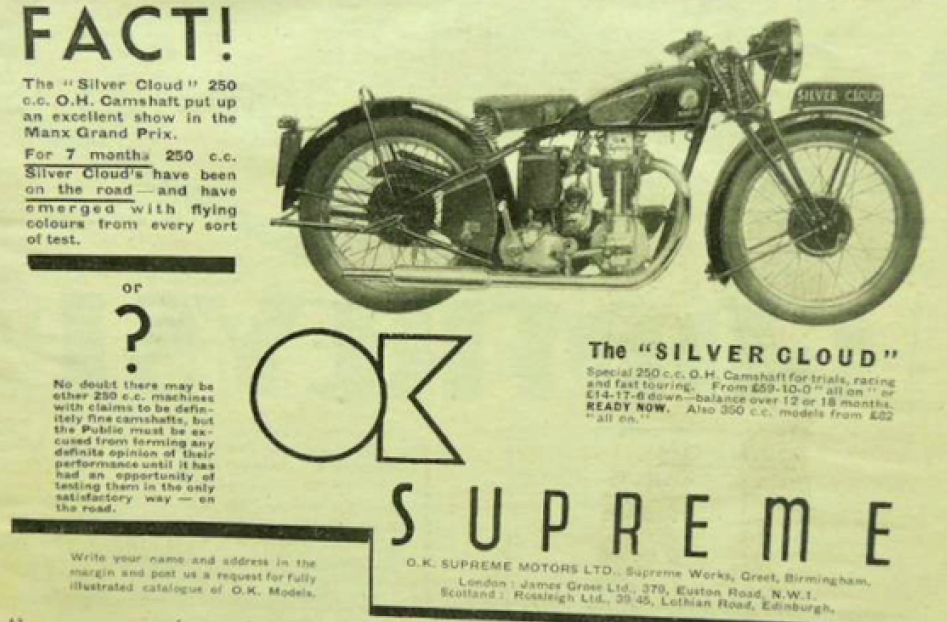

(493cc Excelsior) 63.93mph; 2, HL Brooke (499cc Rudge); 3, SW Cooper (495cc Sunbeam). Next on the programme was the ‘250’ race over ten laps, run in a single heat. Our old friend Paddy Johnston (246cc Cotton) celebrated his first visit to Donington by leading the race all the way, doing pretty well as liked with the rest, of the entry. His nearest rival was TA Hampton, on a camshaft OK Supreme, but Paddy had the legs of him and romped home an easy winner. There was very little of interest in this race, for after the fourth lap the order of the procession—even of the back markers—remained unaltered, SV Smith (247cc Excelsior) being a consistent third, a short distance behind Hampton. Result, 250 Race: 1, P Johnston (246cc Cotton) 59.12mph; 2, TA Hampton (246cc OK Supreme); 3, SP Smith (247cc Excelsior). There was another run-away win in the 350cc race, M Cann (348cc Norton) being quite invincible. Probably the story would have read differently had not HL Daniell (346cc AJS) had the misfortune to stop his engine at Starkey’s Corner when he was lying third on the third lap. At first CVM Booth (348cc Velocette) set the pace, but after the end of Lap 2 he was forced to play second fiddle to Cann. He did this throughout the race, riding very consistently. Daniell restarted a long way behind, but by dogged persistence he rode from 15th on the 4th lap to 5th at the finish—not a bad effort. WG Wright (348cc Velocette) came along well to finish in 3rd place after a scrap with N Croft (348cc Rudge), who was later forced to retire. Result, 350cc Race: 1, M Cann (348cc Norton) 65.20mph; 2, CVM Booth (348 Velocette); 3, WG Wright (348cc Velocette). There was more excitement in the 500cc solo race, in spite of the fact that Norman Croft (499cc Rudge) ran away with it. Indeed, it was this running away that provided the excitement, for, in riding as he did, Croft smashed a 10-lap record by a handsome margin, and at the same time won the Craner Bowl for the best time of the whole year. Heat 1 of the race was not very interesting, but a word must be said for WG Wright (348cc Velocette), who was riding splendidly with a long lead when he had the misfortune to fall and bend things. He carried on and finished third in his heat after a fine effort. Nobody in Heat 1 was fast enough to figure in the final placings, Croft (499cc Rudge), Cann and HL

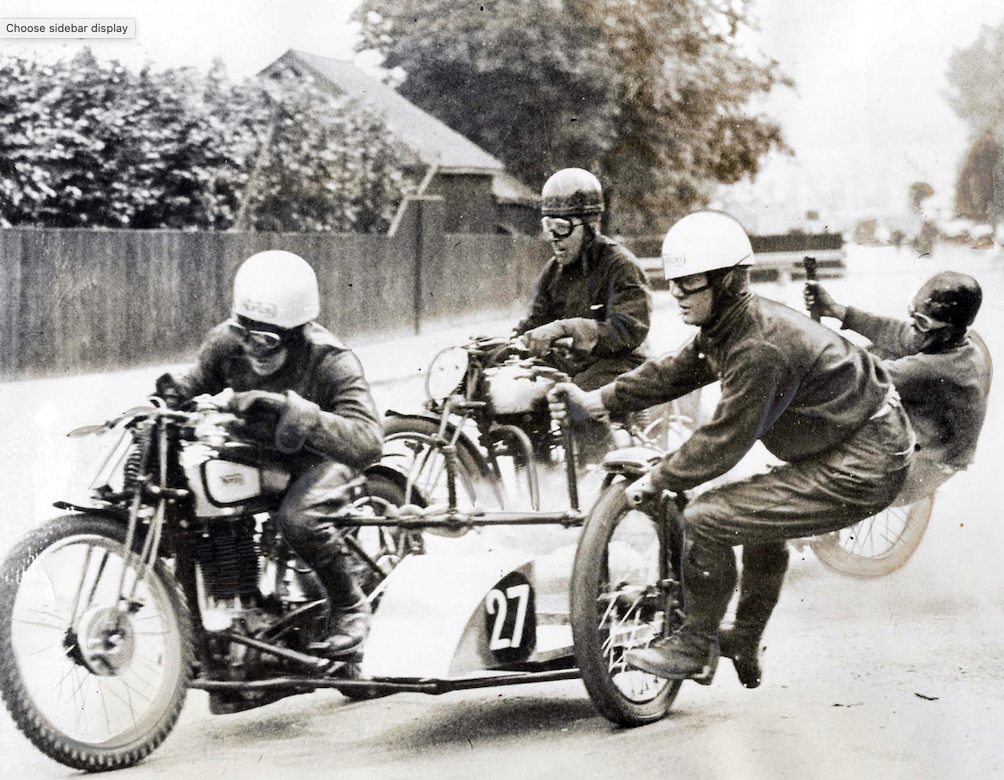

Daniell (490cc Nortons) setting too hot a pace for them. Daniell for once was outridden; he did not seem to be at home on a new machine and steadily dropped away from the two leaders. It would, in fact, have been a very good man indeed who could have held Croft in this event, and he deserves a full measure of praise. Result, 500cc Race: 1, N Croft (499cc Rudge), 67.1mph; 2, M Cann (490cc Norton); 3, HL Daniell (490cc Norton). The 600cc sidecar race was a grand one—a real fight from start to finish—with Kim Collett (490cc Norton s.) rather dominating affairs. He was not allowed to have it all his own way, however, for WH Rose (596cc Norton sc) was.chasing him madly, and actually pushed his nose in front and held it there for three laps. Collett, thinking this was hardly good enough, really put his skates on, slid ahead again, and refused to be caught thereafter. All this time Rose was being harried by LW Taylor (490cc Norton sc), and it was all he could do to keep in second place. The finish was marvellous. These three riders crossed the line in a bunch, and a good-sized blanket would have covered them all. Result, 600cc Sidecar Race: 1, Kim Collett (490cc Norton sc) 56.66mph; 2, WH Rose (596cc Norton sc); 3, LW Taylor (490cc Norton sc). On paper the unlimited sidecar and three-wheeler race looked good, for the interest included Collett and his big Brough, and Henry Laird on his supercharged Morgan. Laird started with a handicap of 100sec, and everyone was eager to see whether he could catch the rest of the field. He set off at a great pace with the flying Brough as his object. But success was denied him, for things happened to the engine and he was forced to pack up after a couple of laps. Meanwhile Collett was going wonderfully well and had attained a tremendous lead. On the fifth lap, however, Rose was almost on his tail, and it was obvious that something was wrong. Something was wrong. Collett did not appear again, and Rose and Taylor were left to fight it out. They were the only two finishers, and less than two seconds separated them at the end. Result: Unlimited Sidecar Race: 1, WH Rose (596cc Norton sc) 55.99mph; 2, LW Taylor (490cc Norton sc). Lastly came the unlimited solo race, and Daniell was obviously out to beat Croft this time. Croft, however, was in altogether too joyous a mood, and although Daniell got in front for a few seconds Croft romped ahead again, riding a great race. Cann battled along in great style, coming in third, and these three went quickly enough to deprive all others but one of a replica. Result, Unlimited Solo Race: 1, N Croft (499cc Rudge) 66.66mph; 2, HL Daniell (490cc Norton); 3, M Cann (490cc Norton); Replica, CVM Booth (348cc Velocette).

THE FOURTH BRIGHTON SPEED TRIALS were hosted by the Brighton & Hove Motor Club along a half-mile straight on Madeira Drive. Cars dominated the trials in numbers, if not performance, and Eric Fernihough dominated the motor cycle classes. He won the 250 and 350cc classes on Excelsior-JAPs; CB Bickell won the 600c class on a 499cc Ariel and Ferni’ rode 996cc Brough Superior-JAPs to win the unlimited solo and sidecar classes and, finally, the Special Class at 88.7mph—and that was the fastest run of the day. The fastest car run was 79.41mph by RO Shuttleworth in an Alpha Romeo; Forrest Lycett managed 66.18mph in an eight-litre Bentley and John Cobb’s mighty 23-litre Naipier-Railton could only manage 78.44mph. Motor Sport’s man at the seaside noted: “Fernihough’s speed of 88.7mph on a solo Brough-Superior motor-cycle will give further material for the bikes vs cars acceleration controversy, and only a Merc or an Auto-Union could have rivalled this performance.”

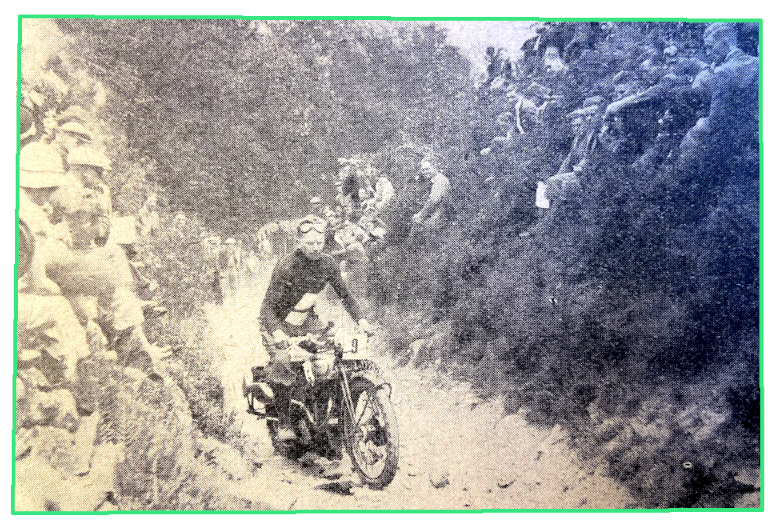

“TO HOLD AN OPEN TRIAL a long way from home requires courage and foresight, otherwise detail is apt to be faulty on the ground chosen. The Wood Green and District MC, in travelling all the way from the northern edge of London to hold its sixth annual Clayton Trophy Trial, was certainly not lacking in boldness in the conception, and, as everyone said who took part last week-end, the organisation lacked nothing in perfection. There is always a good chance, too, when a trial is run on ‘foreign’ ground, of making a gift of the main pots to some of those who know every gully and pitfall of the selected obstacles. This did not exactly happen in the case of the Clayton Trophy Trial, because Ken Wilson, the winner, probably was on quite strange ground. But he does knew the tactics necessary for rough and stony going. Ken Norris, the runner-up, rides regularly in this territory, and might have been tipped as a likely winner. Two of the class award winers, at any rate, have been trained on rocks and boulders. It was quite a short affair as open trials go. The route was only about 36 miles long, starting and finishing at Longnor, near Buxton, and never getting much more than about five miles away from that somewhat quiet village, but there were more than 20 observed sections, not to mention a ‘special test’ section, observed only to decide ties; this section had a dozen sub-sections, the shortest of which was only about three yards! Timekeeping did not enter into the affair at all. As a competitor you just kept going and only retired (a) if the model wilted, (b) if you ‘fell behind the general body of competitors’, and (c) having done so were overtaken by the rear marker marshal—who presumably was not expected to fall by the wayside himself! Some of the officials had ridden all

night to reach their jobs, and one of these, who was to do a large share of route marking, discovered a broken fork spindle on arrival at Longnor. Did the organisation fall down? Not likely! A tommy bar was pushed through the holes, the ends burred over and the job carried through according to plan. Of the 84 entries the North provided some 30 or so, the Midlands a handful, and all the rest were from the South, with, naturally, South Midland Centre riders predominating. Probably all except the Northern riders were more at home on mud and slime than on the bumpy, rocky stuff that the Longonor-Buxton area presented last Sunday. For the dry weather and brilliant sunshine had intensified the jaggedness of the outcrops and loose stones. But no one was daunted, and non-starters were very few. E Harris (347cc Matchless) came all the way from Middlesex and then could not start because of a seized fork spindle. F Drew (247cc Levis) was likewise delayed on his way from Warrington with a seized exhaust valve and arrived just too late. F Flintoff (493cc Sunbeam) had had some mishap the day before, so it was said, and so the Bradford Club started one short. Hollinsclough, near Longnor, was the first observed point, and probably the most difficult problem of the trial, and although then route had been kept ‘secret’ some hundreds of spectators were either in the know or had taken a chance, and out of over 70 ascents they saw only half a dozen make really clean climbs of the entire hill. AC Lane (490cc Norton) and G Leonard (490cc Norton) both got off the route when approaching Hollinsclough, and as they were turned back KB Norris (248cc Red Panther) started the ascent. ‘Ah!’ said the locals, ‘our man on his own ground will show how it can he done’—but he footed a little! Then NR Illingworth (248cc Royal Enfield), probably a perfect stranger to the hill, rode it as