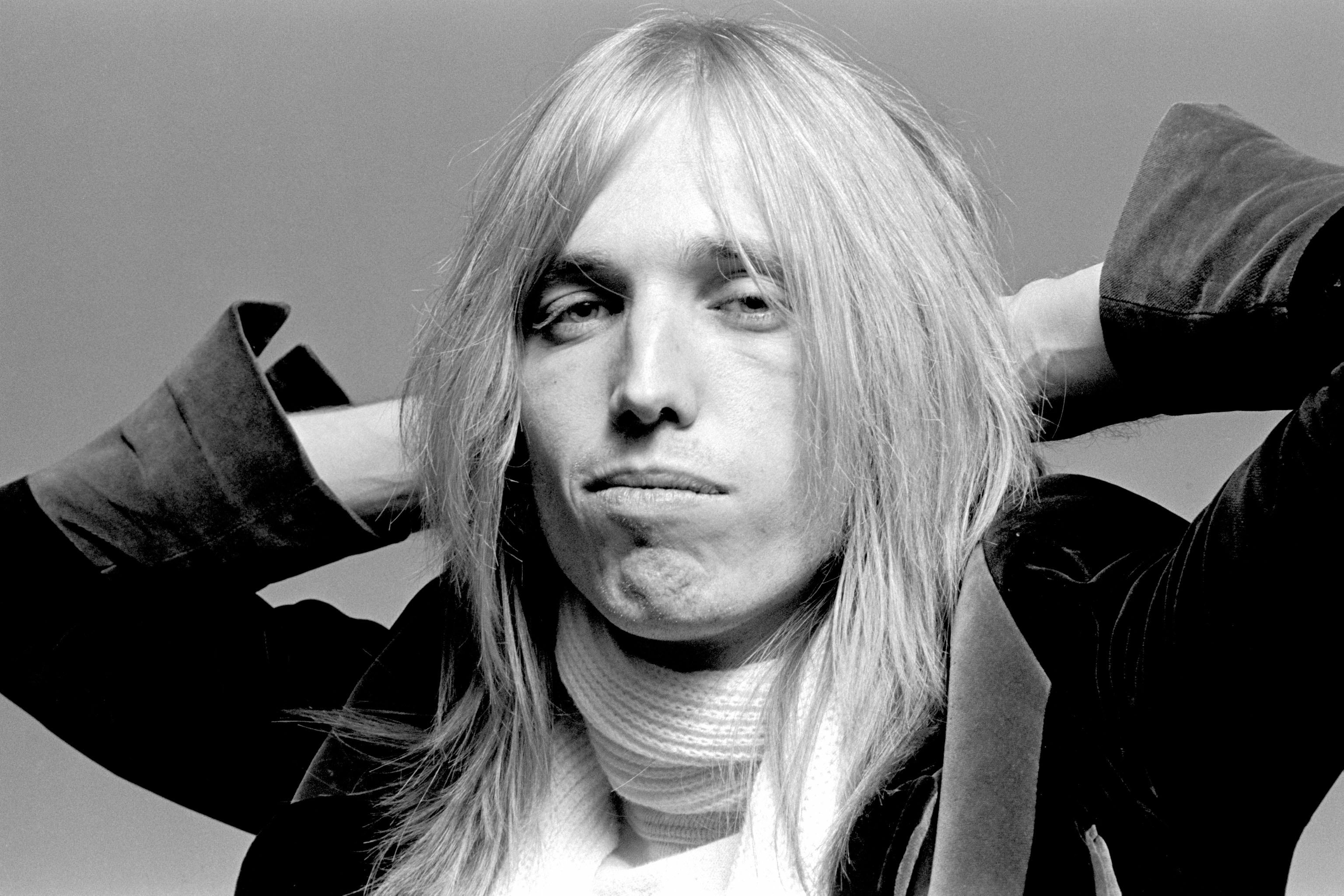

One of my favorite parts of a work trip to Tom Petty’s Malibu house would come at the end of a visit, when he’d walk me out to my rental car. He didn’t actually walk down the driveway so much as he ambled, leaning into it a little. Sometimes he leaned a bit too much and had to catch himself, like he was always slightly off balance but never going to go down. Our interview sessions typically lasted more than four hours, with a meal in the middle, and we’d both be a little wiped by the time we wrapped. But work would be over, and there was an openness to the conversation, even if it remained focused on music. The subject might be Randy Newman or the Lovin’ Spoonful or Elvis or Ann Peebles. But no one, no one, was happier we’d stopped talking about Tom Petty than Tom Petty. This was a man who wanted to glory in the music that had raised him, not the music he’d made. Other people could talk about that.

On the night the Lovin’ Spoonful was the subject, Petty stopped in the driveway, halfway to my car, taking a long drag on his cigarette before launching into a recitation—and I mean a recitation—of the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Nashville Cats.” He may as well have been Allen Ginsberg or Langston Hughes, some poet letting the thick substance of language run through him. He knew every word of the song by heart, and I got the feeling he still couldn’t believe how good those words are. “Nashville Cats/ Been playin’ since they’s babies/ Nashville Cats/ Get work before they’re two.” He did the whole song, slowly, like it was performance art. Surrounded by California plantings, stars above us in the Pacific sky, with Petty turning a song back into a poem: I felt lucky to be witness to this. Whether it was his intention or not, he was letting me in on his profound appreciation for this music. At times like that, I felt he was paying back a debt, remembering what he got and when and where. No one I’ve met in music is, or was, more real about his or her love for the stuff.

It took several years to write my biography of Petty. There were a lot of walks out to the rental car. But I knew enough to savor it, not to rush the conversations that would give the book its backbone of story. If 45 minutes went to talking about Herman’s Hermits or Big Mama Thornton, so be it. He was giving me the time, and I took every bit I could. When my own divorce slowed the process, Petty was quick to let me know that I should focus on surviving that ordeal. He’d been through one, knew the territory. The day I talked to him about a marriage officially ending, we did a shorter interview, after which he wrote notes to my sons, letting them know he was thinking about them, wishing them luck in “the new house.” That may have been the only time the subject wasn’t music. But we both knew that music was the best way to survive the thing under discussion. There was, of course, a difference between us. I survived by listening to Tom Petty songs; he survived by writing them.

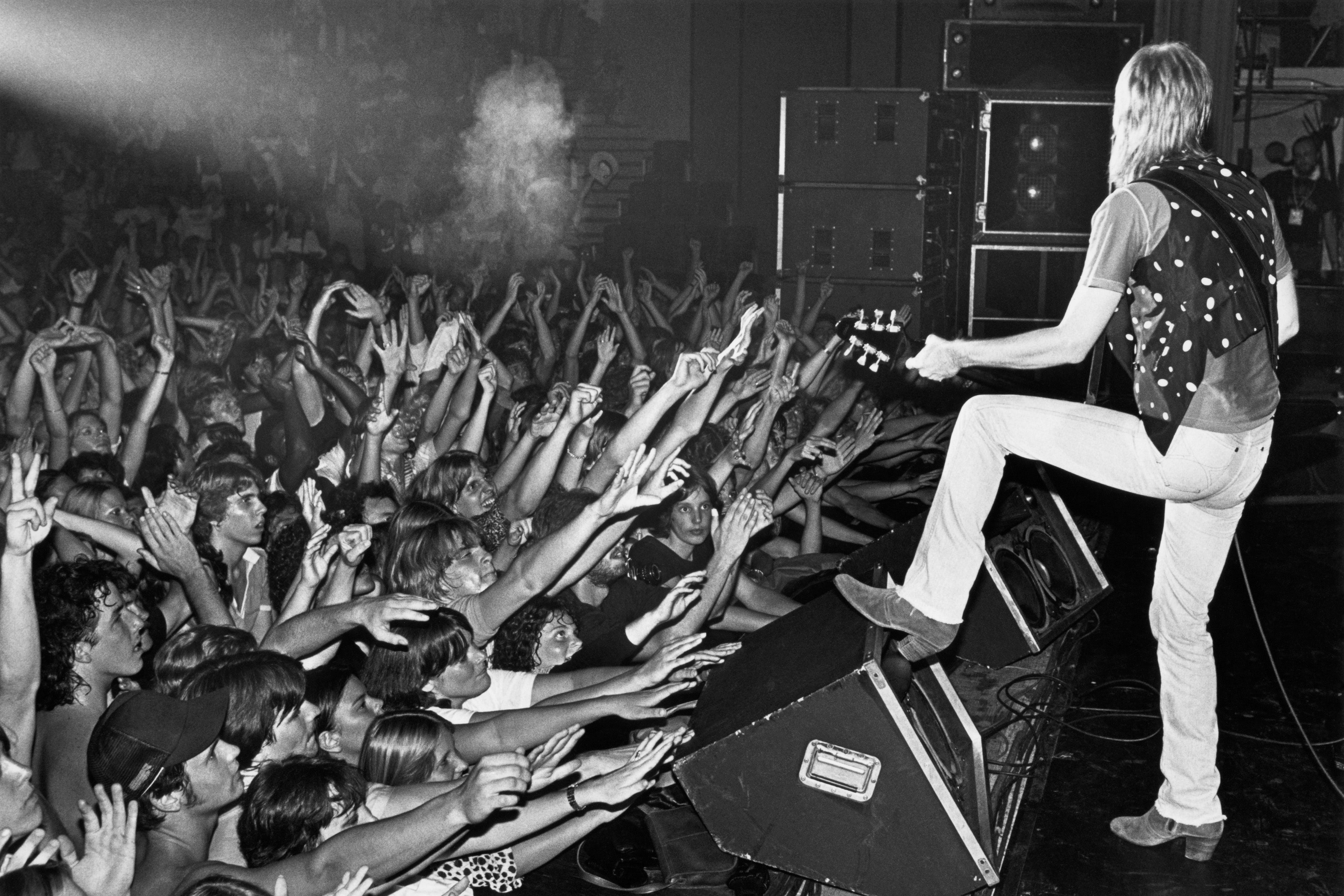

When I first met Petty, I wasn’t much older than my sons are now. And I can assure you that he didn’t look at me and see his future biographer. I was a kid with a chipped tooth in the opening band. As a guitar player, I think I was making my way toward learning a fourth chord. But Petty brought my band out on tour, and likely had a laugh as we drank our way through the summer, feeling inadequate in the company of the rock ’n’ roller we most admired. On many nights, I went out into the crowd and watched Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers do what they did. I could lose myself there.

That was 1986, I think. Petty was only partway through what would ultimately be a long, remarkable career. One of American entertainment’s most beautiful careers. At that moment, however, there was concern that the artist’s momentum was slowing. Petty and his band, the Heartbreakers, were supporting Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough). Relative to what they were accustomed to, ticket sales were soft, album sales softer. The group was out backing Bob Dylan before and after the Let Me Up tour, at times belonging more to Dylan than to themselves. In hindsight, it was a period that had all the earmarks of searching and uncertainty. But that would change with the next recording, Full Moon Fever, Petty’s first solo album. A smash. Just as it would change again with Wildflowers. Or just as it had already changed with Southern Accents. And Damn the Torpedoes. In fact, for all his abilities to create a sound that was decidedly his own, Petty would never be guilty of making the same record twice. He reinvented, broke, and rebuilt, did what he needed to do to adhere to the dictum passed down by the Beatles (and, yes, also Ezra Pound): make it new. Yet he was always what he was: a man with a real rock ’n’ roll band behind him, plugged in and ready to go. His searching and uncertainty in 1986, far from being particular to that moment in his career, was really just a part of his process, from the Heartbreakers’ debut forward. A restless artist, rarely satisfied for long, he went his whole career wanting to make that next record great.

Tom Petty showed us that rock ’n’ roll is a thing of infinite possibilities. Two guitars, bass, drums, and keyboards: However limited it looks on paper, in practice it’s an almost sculptural medium, stunning in its plasticity, something that can always be given a new shape. But just because rock ’n’ roll is infinite in its possibilities didn’t mean it would go forever. And it didn’t, really. But perhaps no one more than Tom Petty lived it to the end with such joy, such commitment to seeing this form take new forms. No one, I came to believe, was less ready to see rock ’n’ roll lose its central place in American popular music.

As has been noted many times, Petty met his hero, Elvis Presley, on a movie set in Florida. He shook the star’s hand, thanks to an uncle in the film industry. But Petty also went on to form a band with a Beatle, George Harrison. And Bob Dylan. And Roy Orbison and Jeff Lynne. Artists like Del Shannon, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash worked with Petty. A lifelong student of the Byrds, Petty, just before his death, finished an album with original band member Chris Hillman, having already enjoyed a long musical friendship with Hillman’s old bandmate Roger McGuinn. It seemed that the history of popular music knocked on Petty’s door, attracted by his cool, by the mind and the humor, by the sheer musicality of the man. He may not have sold himself as rock ’n’ roll’s ambassador to the world, but that’s only because Tom Petty didn’t sell himself as anything. In the self-mythologizing department, he had the material to create one hell of an act. But he didn’t have the stomach for it. He was thinking about that next record.

Since I was a preteen, I’ve been waiting for that thing he was thinking about. It made my world richer, the anticipation around a new recording backed by the assurance that it would, as always, be good, really good. When there was trouble in my world, generally involving a girl, I always had a new song to go to. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers were and will always be a part of the fabric of my life. And having talked to all kinds of fellow fans, I know I’m not alone in this.

There’s a temptation to say that this day marks the official end of the rock ’n’ roll era. But that’s both a little too neat and a little too saccharine. That the-day-the-music-died approach would surely get a quick rolling of the eyes from Petty and a sharp dismissal. Yes, if rock ’n’ roll’s situation is judged by the state of the charts and the sound of mainstream radio, it’s over. Has been for a while. But the most significant parts of the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle have never been lived up there on the higher floors. It happens in the shitty clubs and crappy cars where the music plays. Rock ’n’ roll has always been a thing that has its most complete moments somewhere out on the margins, largely out of view. Take a bus ride with a band, and almost inevitably they’ll start talking about their earliest tours. They’ll remember the soundman’s name from the club they hated but played a hundred times and, really, loved. They’ll go back to a time before they were treated like something special. Petty never lost touch with that time and those places. He lit up when he recalled the clubs in Gainesville where he and the Heartbreakers, who were not yet the Heartbreakers, stumbled toward their art. At the end, he remembered the beginning. You could hear that in the music.