Souterrain

An underground structure consisting of one or more chambers connected by narrow passages or creepways, usually constructed of drystone-walling with a lintelled roof over the passages and a corbelled roof over the chambers. Most souterrains appear to have been built in the early medieval period by ringfort inhabitants (c. 500 – 1000 AD) as a defensive feature and/or for storage.1

Binders Cove souterrain, Dromara, Co Down, NI

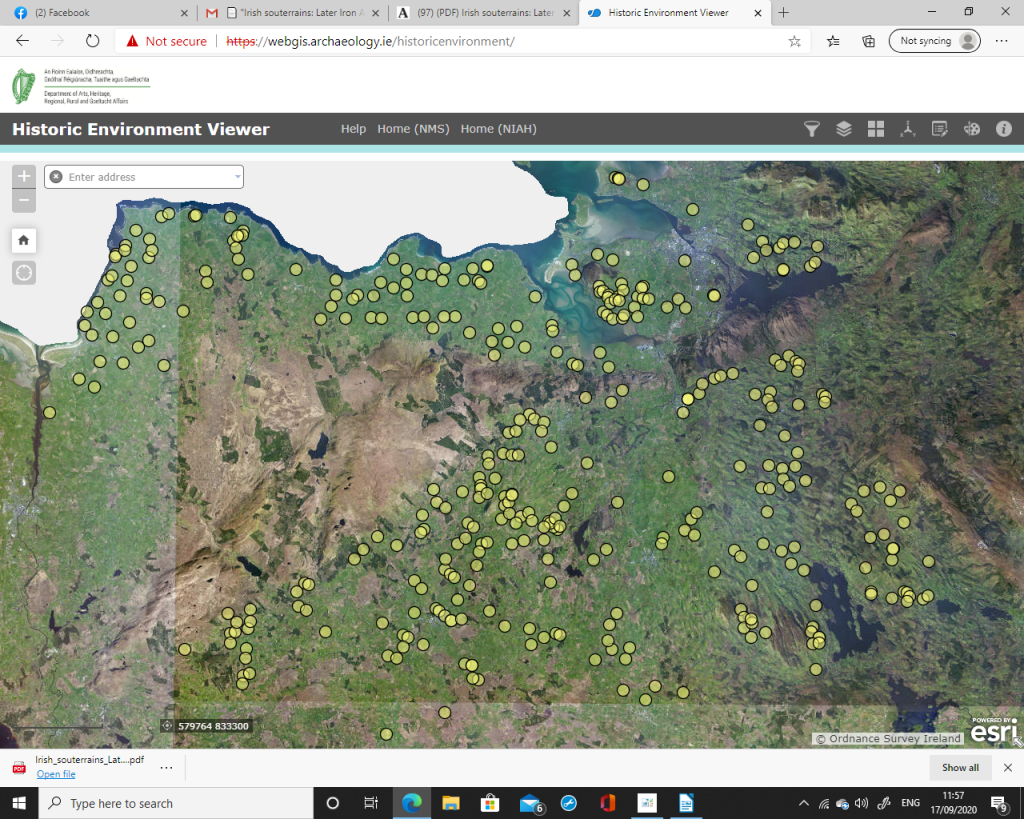

There are 445 souterrains in Co Sligo, 136, in Co Donegal, 472 in Co Mayo, 43 in Co Leitrim, 111 in Co Roscommon, 554 in Co Galway and 15 in Co Longford.

Souterrains in Co Sligo.

So you can see that there are some differences in the number of souterrains (that have been identified) in different counties. ‘Souterrains have been found in almost every part of Ireland, over a thousand are known, or have been recorded, but their distribution is very uneven. This is surprising, for judging by the distribution of the contemporary ringforts the density of human habitation was fairly even, avoiding only land above about 200 metres in height and peat bog.’2

‘The distribution of souterrains is very uneven in Ireland, with the greatest concentrations occurring in north Louth, north Antrim, south Galway, and west Cork and Kerry. Lesser numbers are found in counties Meath, Westmeath, Mayo, north Donegal, and Waterford. Other counties, such as Limerick, Carlow, and Wexford, are almost completely lacking in examples.’3

Of course, souterrains are not only found in Ireland. ‘Souterrain (from French sous terrain, meaning “under ground”) is a name given by archaeologists to a type of underground structure associated mainly with the European Atlantic Iron Age.

These structures appear to have been brought northwards from Gaul during the late Iron Age. Regional names include earth houses, fogous and Pictish houses. The term souterrain has been used as a distinct term from fogou meaning ‘cave’. In Cornwall the regional name of fogou (Cornish for ‘cave’) is applied to souterrain structures. The design of underground structures has been shown to differ among regions; for example, in western Cornwall the design and function of the fogou appears to correlate with a larder use.’4

There seems to be two distinct types of souterrain in Ireland.

‘Tunnelled souterrains

These are found wherever the bed-rock or sub-soil is firm enough for tunnelling. The simplest are straightforward burrows whose spoil was removed through the mouth, and are necessarily limited in their complexity). Nevertheless the longest Irish souterrain known is of this type, being at least 130 metres long with at least eight oval chambers,’

‘Dry stone Souterrains

Souterrains of this constructional class are usually found where the natural rock or clay is unable to sustain a tunnel, but because the technique allows very sophisticated and complex variations they are also found where tunnelling would have been possible. A dry-stone souterrain was constructed, in a square-sectioned trench, of dry-stone walling usually slightly corbelled inwards, capped by large stone lintels and topped with soil to the surface, which is seldom more than 1metre above the bottom of the lintels.’5

As mentioned above, the debate over their use is raging down the corridors of academia. ‘The function of the souterrain has long been the subject of debate and the most accepted opinion is that they were used primarily as a place of refuge and occasionally as a storage site.

It’s perhaps harder to accept that these – hard to access – tunnels were where people stored their everyday goods but, seen as refuges from quick enemy raids, where the object would have been to capture people , they must have been effective. It would have been a very confident raider who would have been the first to crawl down a dark tunnel into the unknown with an unknown number of people, who knew the layout intimately, ahead of him in the dark.’6

For such a large number of sites, there has been a miniscule amount of physical evidence recovered from them. This makes it very difficult to both date them and assign a purpose to them. Virtually all known souterrains are associated with a rath. Now this may not be too helpful, as the jury is out on what purpose raths had. However, if we accept that a rath was probably a farmstead, with the bank and ditch being the equivalent of the garden wall around the farmhouse, then a souterrain may have been the equivalent of a combination larder, valuables safe and panic room. The early medieval saw much fighting and jostling for position between kings and chieftains throughout Ireland.

LC1031.1

Oedh Ua Neill went with a large army eastwards,

around the son of Eochaidh, when he carried off

three thousand cows, and one thousand and two hundred

captives.

LC1031.2

A hosting by the son of Eochaidh into Uí-Echach,

when they burned Cill-Combair with its oratory,

and killed forty clerics, and carried off thirty captives.

LC1042.1

Ferna-mór-Maedhóig was burned by Donnchadh,

son of Brian.

LC1042.2

Glenn-Uissen was burned by the

son of Mael-na-mbó, and the oratory broken, and one

hundred persons were slain, and four hundred taken out

of it, in retaliation for Ferna-mór.7

The taking of slaves and cattle during raids into neighbouring kingdoms would have been a regular occurrence, as well as the danger of foreign raiders from Britain and the Viking territories.

‘When the Vikings established early Scandinavian Dublin in 841, they began a slave market that would come to sell thralls captured both in Ireland and other countries as distant as Spain, as well as sending Irish slaves as far away as Iceland, where Gaels formed 40% of the founding population, and Anatolia. In 875, Irish slaves in Iceland launched Europe’s largest slave rebellion since the end of the Roman Empire, when Hjörleifr Hróðmarsson’s slaves killed him and fled to Vestmannaeyjar. Almost all recorded slave raids in this period took place in Leinster and southeast Ulster; while there was almost certainly similar activity in the south and west, only one raid from the Hebrides on the Aran Islands is recorded.

Slavery became more widespread in Ireland throughout the 11th century, as Dublin became the biggest slave market in Western Europe. Its main sources of supply were the Irish hinterland, Wales and Scotland. The Irish slave trade began to decline after William the Conqueror consolidated control of the English and Welsh coasts around 1080, and was dealt a severe blow when the Kingdom of England, one of its biggest markets, banned slavery in its territory in 1102.’8

‘As I have indicated the average ringfort was the defended farm of a free farmer, whose wealth in portable valuables, judging by the excavation of such sites and by contemporary descriptions, was not very great. The main items of interest to raiders would have been livestock (and perhaps occasionally humans, for sale as slaves), and there can be very little doubt that the raiders would have been from outside the tribal area in which they were raiding. For any small band of pilferers, and we can be certain that most raiding parties were small, it would have been suicidal to wait around long enough to starve the occupants of a souterrain into submission, and allow the surrounding farmers to rally.’9

The souterrain may have been the last, desperate attempt to avoid death or slavery.

1. https://webgis.archaeology.ie/NationalMonuments/WebServiceQuery/Lookup.aspx#SOUT

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Souterrain

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Souterrain

6. http://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/yourplaceandmine/down/A1956017.shtml

7. https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100010A/index.html