As a new biopic of the musician hits cinemas, we celebrate the women in his life such as Linder Sterling and Patti Smith

- TextAlex Denney

There’s a moment in England Is Mine where a young Johnny Marr knocks at Morrissey’s door, like a nervous suitor waiting for his first date. The rest, as they say, is history. But what might have been the start of a beautiful bromance serves as a full-stop in Mark Gill’s biopic of the former Smiths frontman, which instead trains its lens on the women in the teenage Morrissey’s life – his friend Anji Hardie, his beloved mum Elizabeth Dwyer and artist Linder Sterling.

“Morrissey’s relationships with the women in the film were far more important to me than his vegetarianism or his sexuality,” says Gill, a fellow native of Manchester’s Stretford neighbourhood, who instinctively recognised the humdrum world Morrissey painted in his early releases with the band. “He comes from a very large matriarchal family, and they’re not gonna take any shit – they still don’t take any shit.”

Women have always loomed large in Morrissey’s work, from his most famous lyric, “I am the son and heir of nothing in particular” – a lift from George Eliot’s Middlemarch – to his sleeve art for The Smiths’ records, which mapped out a new iconography of brassy-as-fuck, working-class women. Even the title track to The Smiths’ masterpiece The Queen Is Dead can be read as Moz’s attempt to reconcile his own overweening mother-love with the hated female authority figure of our reigning monarch: “When you’re tied to your mother’s apron no one talks about castration,” indeed.

To celebrate the film’s release, we celebrate some of the inspiring women in Morrissey’s life.

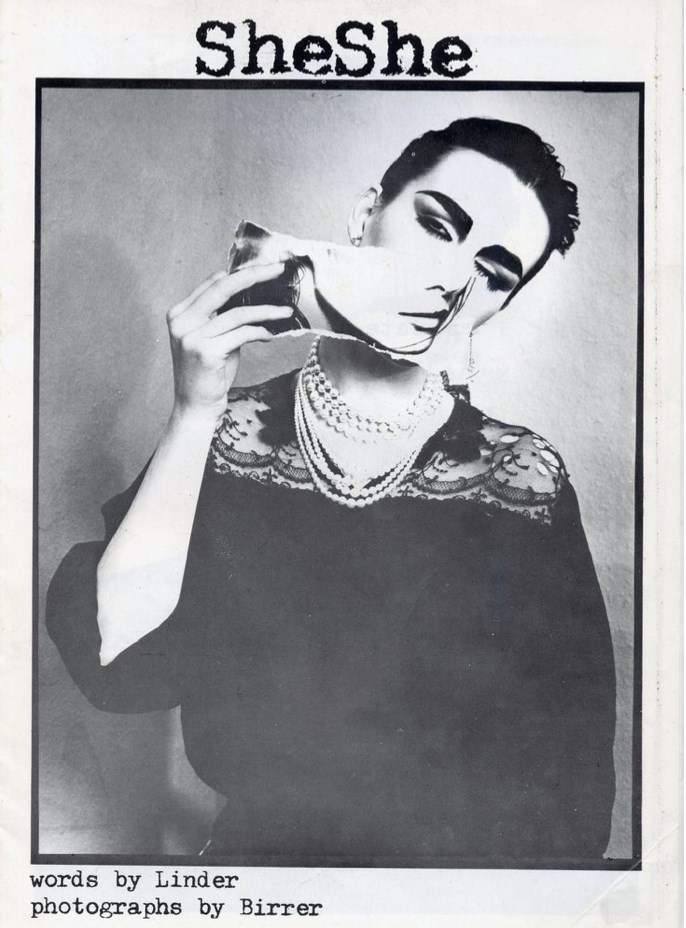

Linder Sterling

Sterling plays a crucial role in England Is Mine, cajoling Morrissey into taking his rightful place on stage after meeting him at a soundcheck for a Sex Pistols gig. An artist and musician whose cut-and-paste aesthetic satirised sex and commodity fetishism – her work graces the sleeve for Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict single – Sterling’s graveyard walks with the singer inspired The Smiths’ song Cemetery Gates. “We just walked and talked,” Sterling told the Guardian in 2014. “We had very little money and lots of the same books rattling around in our heads. Morrissey was reading all the same feminist texts as I was, so we shared the same language and the same discontents.” One of Sterling and Morrissey’s comic creations found its way into Gill’s film via the character of Christine, a nice-but-dim office worker who finds herself inexplicably drawn to Morrissey. “They used to call certain types of women when they were growing up ‘Christine Cowsheds’,” says Gill. “So we took the name for that working-class girl who may not have been exposed to things or had the education... Christine doesn’t have that filter, she just says what’s on her mind. I love that about people.”

Pat Phoenix

Morrissey’s love of Coronation Street is the stuff of Smiths-fan legend, with the story going that he once submitted a script for the show to Granada only to be politely rebuffed. If that seems strange, remember that the long-running soap’s roots lay in the kitchen-sink realism that brought working-class voices to the screen as never before in 60s Britain – and no one embodied the steely indomitability of the show’s matriarchs better than Pat Phoenix AKA Elsie Tanner, who featured on the cover of The Smiths’ 1985 single Shakespeare’s Sister. Perhaps identifying with Tanner as a strong matriarchal figure in the mould of his own mother, a librarian who fostered his love of literature from an early age, Morrissey interviewed Phoenix for Blitz in 1985. In the must-read piece, Moz hails the actor as “the screen’s first ‘angry young woman’… It was the skill of Pat’s acting that earned Elsie great distinction as mother, sister and lover to millions.”

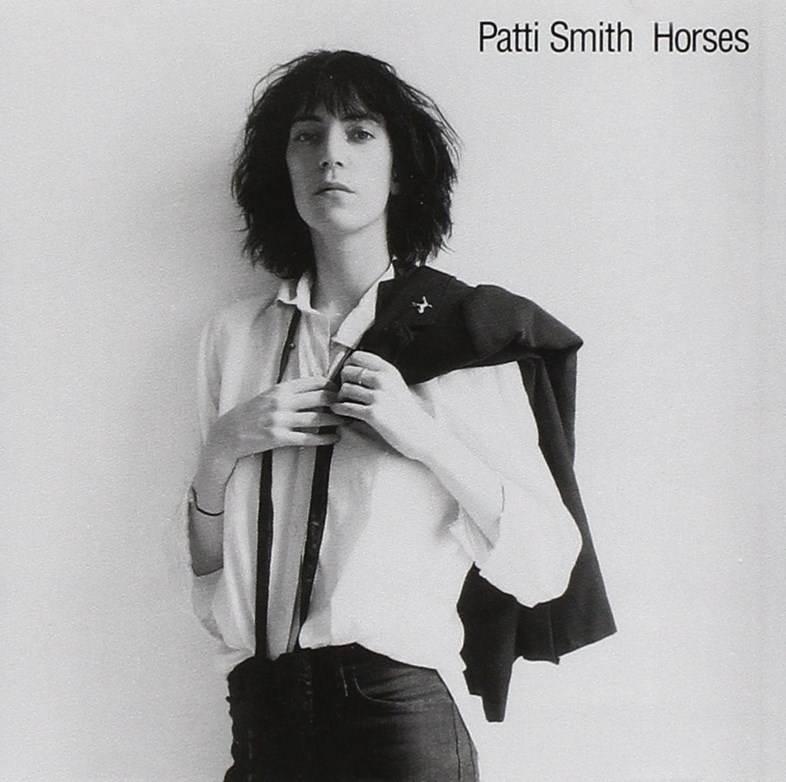

Patti Smith

Smith’s role at the vanguard of the 70s New York punk scene made her an idol to the young Morrissey, who met Johnny Marr outside one of her concerts and sported an unruly mop of hair in his pre-quiff days as a tribute to the rock’n’roll poet. Morrissey remembered falling for her epochal first album Horses in an interview with The Telegraph from 2011: “I sat up all night listening to it on a very tiny stereo, and I couldn’t stop. And I thought it was extraordinary because it was the voice of somebody who perhaps had felt unattractive all their lives, in every way. Yet here they were, singing about it, and seemed to know a way to make the misfortune of their lives become attractive.” The pair eventually became friends, though not before a 1978 encounter at a fanzine conference where a horrified Morrissey saw Smith ask a teenage fan about the size of his penis.

Shelagh Delaney

“I’ve never made any secret of the fact that at least 50 per cent of my reason for writing can be blamed on Shelagh Delaney,” Morrissey told NME in 1996, and certainly, the Salford-born playwright’s influence can be felt everywhere in The Smiths. The band’s 1987 single Sheila Take a Bow is a direct – if misspelled – nod in her direction, while This Night Has Opened My Eyes interpreted her best-known work, A Taste of Honey, which exploded the hypocrisies of class-bound Britain on its premiere in 1961. Delaney’s passing in 2011 prompted a moving tribute from Morrissey: “She was attacked for immorality, which, then as now, is proof that you have hit on something,” he wrote. “If you worry about respect you don’t get it. Shelagh Delaney had it and didn't seem to notice it.”

Cilla Black

There are other 60s female singers of a somewhat kitschy stripe that we might have chosen for this spot – Sandie Shaw, for instance, who recorded a cover of “Hand in Glove” with The Smiths as her backing band in 1984 (her Top of the Pops performance of the song is weirdly unmissable). But the late Miss Cilla Black beats her to the punch, not least because of her alleged role in The Smiths’ demise. In 1987, Morrissey wanted to cover Black’s song “Work Is a Four-Letter Word” for the band’s next single, but Marr was less than impressed, complaining that “I didn’t form a group to cover Cilla Black songs.” It was the beginning of the end for The Smiths, but Morrissey remained a fan of Black’s up until her death in 2015. “I’m very grateful for (her) songs,” he wrote, “and it never occurred to me that such people could die.”

England Is Mine is out now.