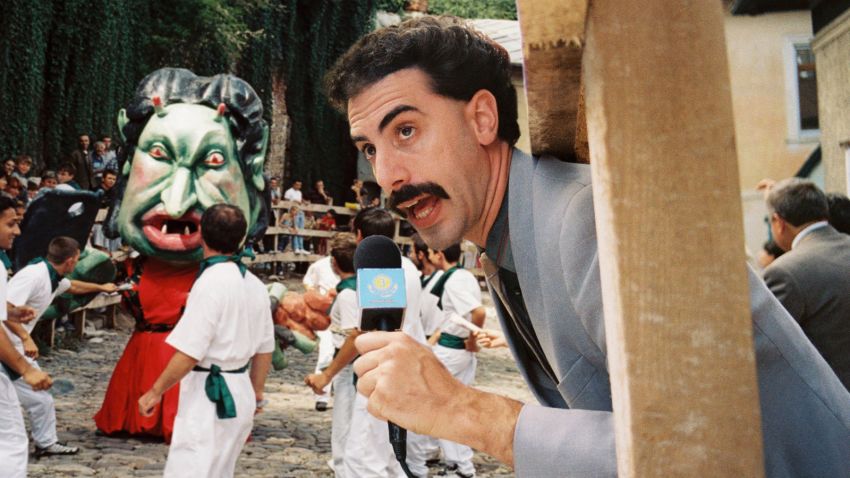

At a moment when people are reassessing racial and cultural caste – and reexamining their insensitivity toward others – it’s worth revisiting the impact of Sacha Baron Cohen’s errant, mustachioed character, Borat, who returned in a sequel on Friday.

While (Western) critics largely embraced Larry Charles’ 2006 mockumentary “Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan,” about a fictional Kazakh reporter played by Baron Cohen, many Kazakh viewers denounced the movie’s cartoonish portrayal of their country, which covers swaths of Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Their reading was that Baron Cohen, who co-wrote and produced the film, “just randomly pointed his finger at a map” and “took the name of our country and our symbols, and that’s it,” Zarina Smagul, 28, told CNN.

Of course, the responses from “Borat’s” Kazakh audience weren’t monolithic.

Serik Sharipov, 33, saw the movie in 2006, when he was studying at the American University in Bulgaria.

“On campus, there were students of many different backgrounds, including many Kazakh students, and a group of us went to see ‘Borat’ in the theater,” he said. “It was a bit of a sensation.”

Sharipov recalled some of his classmates’ defensiveness, how it made sense. After all, at the time, Kazakhstan was still figuring out its identity and how to communicate to the wider world that it had arrived. It was only in 1991 that the nation declared its independence from the Soviet Union.

To a number of Kazakhs, it felt like a punch in the gut that “Borat,” with its crass, Western stereotyping of Central Asians, Arabs and Eastern Europeans, essentially became international viewers’ introduction to the young country.

Take the opening scene. Borat mirthfully presents his hometown to viewers by acquainting them with “the town rapist,” “the town kindergarten,” where kids tote guns, and “the No. 4 prostitute in all of Kazakhstan,” his sister.

Yet as a believer in the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad publicity, Sharipov said that his experience with the film was much more positive.

“On learning that I’m from Kazakhstan, classmates would ask me lots of questions about the country,” he said. “Sure, the first few questions would be silly, and people would want to know how close to reality ‘Borat’ is. But then we’d go into interesting discussions, and I’d share information about Kazakhstan’s history.”

Political realities shaped Sharipov’s response to “Borat.”

“I’m from a country with heavy censorship. I don’t want my opinion or anyone else’s opinion about what is or isn’t proper comedy to limit what we see,” he said. “I don’t think that ‘Borat’ is really about Kazakhstan. But our reaction to the movie is.”

Still, while some of the jokes in “Borat” work, others don’t.

The titular character’s antisemitism, misogyny and racism make for important, if easy, targets of ridicule. The same goes for the Americans who indulge Borat’s situationist slapstick; their morally questionable behavior is there for the audience to skewer. Indeed, “Borat” is at its best when it’s punching up.

For instance, at one point, several White Americans comment to Borat that it’s a shame that there’s no longer slavery in their country. In their ugliness, such lines are reminders that bigotry still thrives in America.

At other times, though, “Borat” seems to be punching down.

“With ‘Borat,’ Baron Cohen reclaimed for ‘First Worlders’ the ‘right’ to mock foreigners from developing nations,” the journalist Inkoo Kang wrote for Slate in 2018. “Only with the Borat accent are the phrases ‘my wife!’ and ‘very nice!’ punchlines we all remember.”

She added: “Baron Cohen’s view of Borat isn’t too dissimilar from how White nationalists here and in Europe view immigrants and refugees: ignorant, violent, prone to sexual assault, unable or unwilling to assimilate. … ‘Borat’ continues to illuminate. But now what it lays bare is the xenophobia we were willing to embrace while pointing fingers at the bigots on-screen.”

Kazakh movie-goers echoed these sentiments, underscoring the film’s uneven power dynamics.

“We were just starting to be proud to be Kazakh. Can you imagine what a slap in the face it was to see a movie that doesn’t show anyone who even looks like you?” Smagul told CNN. “I love comedies. We have a lot of movies in which we, Kazakhs, laugh at parts of our culture. But I also love when research is done before filming.”

Read more from Brandon Tensley:

With “Borat,” she said, it felt as if Baron Cohen had arbitrarily chosen a “foreign-sounding” country in order to say something profound about America. Meanwhile, Kazakhs were left to deal with the cultural course-correction that attends a film such as “Borat.”

Aisana Ashim, 29, was equally direct in her criticism of the movie.

As a journalist and an activist, she said that she wants to shine a light on the issues beleaguering Kazakhstan. According to Human Rights Watch, “Kazakh authorities routinely break up or prevent peaceful protests criticizing government policies,” and “impunity for torture and ill-treatment persists.”

But “Borat,” Ashim explained, warps the attention the country receives.

“While the world laughs, we struggle alone with our problems,” she said, adding that it’s frustrating to hear people defend the movie by noting that it makes fun of America and European countries as well. “That claim is weak because – what do you know about these countries? A lot. You know their culture and history. You can name their famous artists, scientists and politicians. But Kazakhstan isn’t that well known.”

The argument is that “Borat” uses Kazakhstan as a prop, as a means of illustrating issues in America. But the prop itself is discarded.

Maybe “Borat” helps viewers get to know America a little bit better. But nobody walks away with a deeper knowledge of Kazakhstan. Some might even read that last sentence and laugh. Which, of course, is part of the problem.