Advanced Aquatics: The Butterfly Chronicles, Part 2, by Matt Pedersen, as published in the January/February 2019 issue of CORAL Magazine.

THE BUTTERFLY CHRONICLES, Part 2 (read Part 1)

One aquarist’s evolving views on keeping the “Impossible Corallivores”

text and images by Matthew W. Pedersen

Excerpt from CORAL Magazine, Jan/Feb 2019

This article appears in the January/Feburary 2019 issue of CORAL: Click to order this back issue for your collection.

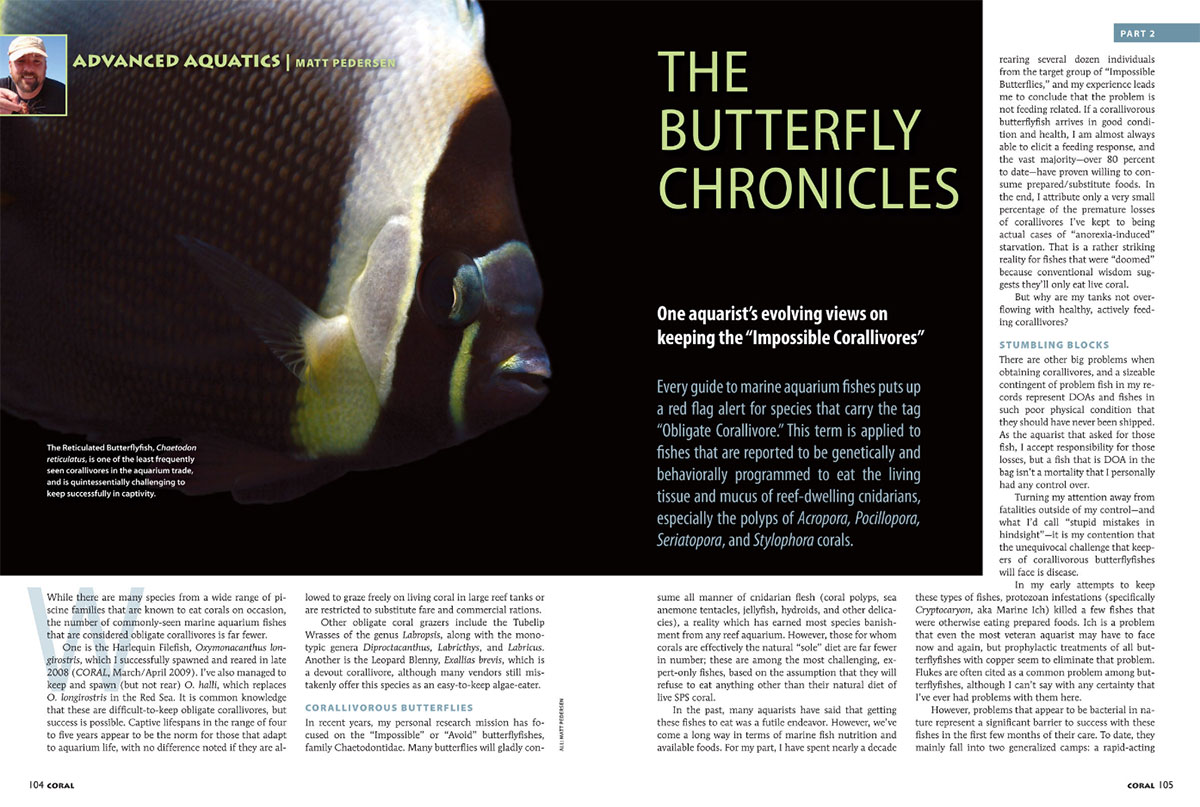

Every guide to marine aquarium fishes puts up a red flag alert for species that carry the tag “Obligate Corallivore.” This term is applied to fishes that are reported to be genetically and behaviorally programmed to eat the living tissue and mucus of reef-dwelling cnidarians, especially the polyps of Acropora, Pocillopora, Seriatopora, and Stylophora corals.

While there are many species from a wide range of piscine families that are known to eat corals on occasion, the number of commonly-seen marine aquarium fishes that are considered obligate corallivores is far fewer.

One is the Harlequin Filefish, Oxymonacanthus longirostris, which I successfully spawned and reared in late 2008 (CORAL, March/April 2009). I’ve also managed to keep and spawn (but not rear) O. halli, which replaces O. longirostris in the Red Sea. It is common knowledge that these are difficult-to-keep obligate corallivores, but success is possible. Captive lifespans in the range of four to five years appear to be the norm for those that adapt to aquarium life, with no difference noted if they are allowed to graze freely on living coral in large reef tanks or are restricted to substitute fare and commercial rations.

Other obligate coral grazers include the Tubelip Wrasses of the genus Labropsis, along with the monotypic genera Diproctacanthus, Labricthys, and Labricus. Another is the Leopard Blenny, Exallias brevis, which is a devout corallivore, although many vendors still mistakenly offer this species as an easy-to-keep algae-eater.

Corallivorous Butterflies

In recent years, my personal research mission has focused on the “Impossible” or “Avoid” butterflyfishes, family Chaetodontidae. Many butterflies will gladly consume all manner of cnidarian flesh (coral polyps, sea anemone tentacles, jellyfish, hydroids, and other delicacies), a reality which has earned most species banishment from any reef aquarium. However, those for whom corals are effectively the natural “sole” diet are far fewer in number; these are among the most challenging, expert- only fishes, based on the assumption that they will refuse to eat anything other than their natural diet of live SPS coral.

In the past, many aquarists have said that getting these fishes to eat was a futile endeavor. However, we’ve come a long way in terms of marine fish nutrition and available foods. For my part, I have spent nearly a decade rearing several dozen individuals from the target group of “Impossible Butterflies,” and my experience leads me to conclude that the problem is not feeding related. If a corallivorous butterflyfish arrives in good condition and health, I am almost always able to elicit a feeding response, and the vast majority—over 80 percent to date—have proven willing to consume prepared/substitute foods. In the end, I attribute only a very small percentage of the premature losses of corallivores I’ve kept to being actual cases of “anorexia-induced” starvation. That is a rather striking reality for fishes that were “doomed” because conventional wisdom suggests they’ll only eat live coral.

But why are my tanks not overflowing with healthy, actively feeding corallivores?

Stumbling Blocks

There are other big problems when obtaining corallivores, and a sizeable contingent of problem fish in my records represent DOAs and fishes in such poor physical condition that they should have never been shipped. As the aquarist that asked for those fish, I accept responsibility for those losses, but a fish that is DOA in the bag isn’t a mortality that I personally had any control over.

Turning my attention away from fatalities outside of my control—and what I’d call “stupid mistakes in hindsight”—it is my contention that the unequivocal challenge that keepers of corallivorous butterflyfishes will face is disease.

In my early attempts to keep these types of fishes, protozoan infestations (specifically Cryptocaryon, aka Marine Ich) killed a few fishes that were otherwise eating prepared foods. Ich is a problem that even the most veteran aquarist may have to face now and again, but prophylactic treatments of all butterflyfishes with copper seem to eliminate that problem. Flukes are often cited as a common problem among butterflyfishes, although I can’t say with any certainty that I’ve ever had problems with them here.

However, problems that appear to be bacterial in nature represent a significant barrier to success with these fishes in the first few months of their care. To date, they mainly fall into two generalized camps: a rapid-acting mouth rot, and what appears to be a more chronic infestation of the skin that fails to respond to a wide range of attempted medications. I have had corallivores live for months with these lesions, all the while gorging on prepared diets.

This C. melapterus exhibits the telltale red lesions indicative of a chronic, undiagnosed disease the author repeatedly encountered. It fails to respond to a wide range of anti-protozoan, anti-fl uke, and antibacterial medications. Fish have lived for months with this condition. Prevention, rather than treatment, may be the best hope in this case.

You may wonder how I can be optimistic about the future with corallivorous butterflyfishes in the marine hobby, but consider for the moment that problems like shipping-related mortality, fish weakened in the supply chain, and disease are not insurmountable. The myth that these fish would refuse to eat anything other than coral sounds far more problematic, but with the vast majority of fishes accepting prepared foods within a couple weeks of care, and multiple individuals living well beyond a year solely on these diets, I would argue that the entire “feeding” problem just isn’t what it used to be.

In fact, the fate of every corallivore that’s made it past four to six months in my care and which was ultimately lost can be linked to more commonplace husbandry problems that have nothing to do with diet, nor with disease. Get the fish to live half a year, and I’m convinced you have a fish that can live for years, maybe decades, unless you do something boneheaded (like leaving the lid off the tank and allowing the fish to jump).

Hard-Learned Lessons

If you’re going to embark on the challenge of keeping a corallivorous butterflyfish, I’ve identified several ways to push the odds in your favor.

1. Start with quality fish. Suffice it to say that any fishes collected with cyanide are likely going to perish regardless of the level of care you offer. Choose vendors that are known for delivering quality fish, but don’t ask them to hold or observe the fish; they’re not equipped to give them the individual attention that only you can give.

2. Buy the fast pass. Don’t make your corallivores wait in line to get to you. The general industry chain of custody is not equipped to offer these fishes any sort of proper diet, so a freshly-caught fish that gets to you quickly will provide you with a much greater margin of error. Let your source know that this is special order for you and that you want to get the fish or fishes delivered as quickly as possible.

3. Be generous in packaging and shipping. In my experience, corallivorous butterflyfishes are very sensitive to shipping stress. I have made it a point to ask even the most experienced shippers to dramatically over-pack specimens compared to what they otherwise would have done. From the perspective of the receiver, the deportment of fish given this level of care shows that it’s a smart move. Be willing to pay for a “first-class luxury ride,” and you’ll reduce the risk of shipping-related mortalities.

Generous over-packing of this Arabian Butterflyfish (Chaetodon melapterus) costs extra, but greatly reduces shipping stress.

4. Attempt to work with moderately-sized fish. It is generally known that the 2- to 3-inch (5 to 8 cm) size range for butterflyfishes seems to be the “sweet spot.” Tiny butterflies lack the fat reserves to endure long journeys or periods without food, which means they starve quickly if not instantly furnished with something they’ll eat. Large, mature butterflies offer a different problem, where they’re generally too set in their food-selection ways to adapt to aquarium life.

5. Provide individual quarantine. Back in the late 2000s, fellow aquarists wondered whether a Harlequin Filefish would learn to eat prepared foods if it saw another individual doing so. I am convinced that there is no “monkey-see, monkey-do” learning behavior we can exploit with these fish, because other interactions tend to get in the way. For example, when I quarantined multiple corallivores in the same aquarium, particularly individuals of different species, the same problem I first encountered with my filefish occurred with the butterflies: once one individual learned to eat prepared foods, it became aggressive towards other fishes in the tank, preventing them from eating and guarding the food source. Any hostile situation in a small isolation tank can quickly lead to the weaker fish being stressed or killed. Individual quarantine is a must—either separate tanks or a tank with dividing walls to create safe chambers.

6. Get ahead of disease. My number one problem with Chaetodontids across the board, not just the obligate corallivores, is a general susceptibility to malaise, especially Cryptocaryon. Thankfully, this lethal protozoan affliction is easily preventable, provided you deal with it from the get-go. Simply quarantining fish and waiting to see if a problem develops isn’t enough; this is a group of fish that needs prophylactic treatment to eliminate problems before they arise. A well-stocked medicine chest for your aquarium fish is a wise investment because when a fish gets sick, you can’t wait half a week to get the medication you need.

My general protocol for newly-arrived butterflies is as follows: A) a 5-to-10-minute freshwater dip administered between the initial drip-acclimation and subsequent release into the quarantine tank; B) copper treatment with Seachem’s Cupramine for a 3-week period, then C) treatment with praziquantel (utilizing Prazi-Pro) to hit any worms or flukes. This process will eliminate the commonly encountered diseases, but at this point it is only half of a full disease-prevention protocol. Avoiding the “mouth rot” and “red lesions” that I’ve repeatedly seen in the later stages of quarantine remains a problem that I struggle with.

7. Maintain excellent water quality. It probably shouldn’t be surprising that a group of fish that is sensitive to shipping-related stress also may have problems with deteriorating water quality. It has been my experience with long-term captive corallivorous butterflies that if I skip a few water changes, I may see a decrease in appetite or other signs of discomfort; this was a very noticeable problem with Oxymoncanthus, too.

8. There is no magic food bullet. While I’ve outlined a highly reliable protocol for training corallivores onto prepared foods by coating coral skeletons with a gel-based diet, there are probably going to be fishes that fail to respond to this technique. (See Part I, CORAL, November/December 2018.)

One of the worst mistakes I made in my corallivore career was attempting to force a fish to accept a food that I was convinced would work, with the logic that “once it’s hungry enough, it’ll eat.” It never ate what I wanted it to, but by the time I conceded the standoff and offered it something it would eat, the fish was simply too far gone to recover. While food-coated coral skeletons are my de facto first offering, I would strongly recommend having Nutramar Ova on standby; this frozen prawn roe is an incredibly powerful enticement to feed. Mussels on the half-shell are readily obtainable and have proven very reliable feeding options as well, although concerns have been raised about them serving as a possible vector for pathogens.

Of course, as I recommend in Part 1, it may be necessary to have live stony corals to sacrifice at the altar of the butterflyfish. My broad view is that these fish do seem to have a general unwillingness to eat anything following transit, but once you elicit a feeding response on anything, you’ve gotten the stubborn fish over the initial impasse. It may take a real living coral to get your foot in the door, but if you can get there, you can almost assuredly get them onto something else.

Do not be afraid to utilize a shotgun approach on top of these initial recommendations. I remember a pair of Vietnamese-collected Blueline Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus septentrionalis) which refused all manners of high-end, quality frozen foods for weeks, but the moment I threw flake food into their tank they plowed through it with enthusiasm.

Sometimes a fish will throw you a curveball; this Melon Butterfly, Chaetodon trifasciatus, investigates a chunk of Nutramar Ova in the water column; it was the first thing this particular fish ate upon arrival. Within a couple weeks, a much wider range of foods were accepted.

9. Keep the tank clean. For a long time, I was a proponent of the idea that allowing algae to grow and uneaten food to sit for extended periods would offer these fishes the time needed to investigate food sources in peace; I generally thought to clean the tank bottom every few days and never scraped the algae. Now, realizing that disease is my biggest problem with these fish, I’m shifting to a much more sanitary approach when it comes to the initial quarantine and training period with these fishes, in an effort to eliminate “habitat” for bacterial and other potential pathogens. There have been many different hypotheses proposed that center around “immune suppression” being the underlying issue that manifests as disease, but one area we can all agree on is that a more stringent maintenance regime can only help reduce risks.

10. Utilize distributive feeding methods. Turning to a more long-term problem, these are fishes that constantly graze in the wild. Like many grazers, they don’t do well on once-a-day feeding regimes. They also rapidly decline if food is withheld for more than a day or two; the adage that a healthy fish can go unfed for a week does not apply to the corallivores. They will be in bad shape and prove difficult to turn around if you force them to fast. I lost one long-term captive directly as a result of a “harmless” fast of a few days; this was truly a hard-learned lesson.

Repashy gel-based diets are an excellent choice for corallivores, as they are able to remain in the tank for a full 24 hours if desired, providing a readily-available food source for the fish to pick at throughout the day. If the fishes can be trained onto pellet feeds, programmatic auto feeders are a wonderful help to the aquarist and the fish will absolutely benefit.

11. Let the corallivores be the stars. It’s my opinion that most of the corallivorous butterflyfishes are not exceptionally assertive or aggressive, with the Chevron Butterfly (C. trifascialis) being a notable exception (I have seen one Chevron kill another, only to itself be killed months later by a Maroon Clownfish). Once you’re looking at the long-term care of a corallivore, why risk all your hard work by placing it in an aquarium already populated by strong-willed fish that may bully or pressure such a treasure?

It may be a little bit surprising, but Butterflyfishes don’t generally love each other; my boyhood dream of a 30-gallon reef tank with several butterflies was ill-advised for many reasons, but aggression between individuals wasn’t one of the problems I had anticipated. If you’re going to try more than one butterflyfish in the final aquarium, give them a fair amount of space (for example, my intended broodstock colony of 10 Foureye Butterflies, Chaetodon capistratus, was given a 300-gallon pond to work with, and that seemed to be enough for each fish to have its own space). Approach cohabitation with caution, and have those quarantine tanks at the ready should your particular pairing or grouping not work!

The author’s longest-running successes to date: an unlikely pairing of a Melon Butterflyfish (C. trifasciatus) with an smaller Arabian Butterflyfish (C. melapterus) which are now around the two-year mark in captivity.

Not All Corallivorous Butterflies Are Equal

After nearly a decade, I am convinced that you have the greatest chance for success with species from the Corallochaetodon group: the Blacktail or Exquisite Butterflyfish (Chaetodon austriacus); Arabian Butterfly (C. melapterus); the Oval Butterfly, often confusingly called the Melon or Redfin (C. lunulatus); and the Melon or “Indian Redfin” Butterfly (C. trifasciatus). I have had a nearly 100% success rate in getting these fi shes to accept prepared foods (the sole outlier being a fi sh that died the moment I put the fi rst dose of Cupramine in the aquarium), and collectively they have the longest lifespans in my care.

My next choice would be from Megaprotodon group of Chaetodontids. The widespread Chevron Butterflyfish (C. trifascialis) is the sole member; it is found in both the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Mainly collected from the Red Sea, the Arabian Butterflyfish an expensive purchase, but may receive better care in the chain of custody due to its higher price tag.

A Bright Future

As I review my efforts with corallivorous filefish and butterflies, time and again the problem of “getting the fish to feed” has not proved to be the barrier it seems. Getting healthy, high-quality fish is vitally important if acclimation and food training is going to work. Sure, they’re picky, but they can be tricked, and we have some great food options to start with. Looking at my records, it’s reasonable to say that if a corallivorous butterflyfish can make it through the first 4-6 months in my care, eating well and avoiding disease, it should remain around for the long haul. All of my mortalities that occurred beyond that timeframe are easily understood husbandry mistakes.

Understanding and identifying the actual problems of corallivore husbandry completely changes my viewpoint. I’m not terribly intimidated by them these days, although I repeatedly state that they still are in the “expert- only” category of husbandry.

Just as we now see Harlequin Filefish welcomed into some reef aquariums, perhaps there will be Chaetodontids in the future? Early experiments housing these butterflies with zoanthids, mushroom polyps, and assorted soft corals such as Xenia, Knopia, Sarcophyton, Sinularia, and Capnella, have shown that these corals will likely be ignored.

I’d like to live to see more Chaetodontids in reef aquariums, perhaps captive-bred butterflyfishes that thrive on prepared foods and are not as vulnerable to the rigors of shipping and handling. Toward this end, there is much work to be done, and we hope to share it with you here in the pages of CORAL.

Readers are invited to add their comments and their own experiences below.

Great article Matt!

Thanks a bunch Mark!

Living in south Florida, I have collected and attempted to keep pairs of Four-Eye Butterflyfish on couple of occations and found them to be very fussy feeders. They were never keen on eating free floating food of any kind. The one thing they ever showed any enthusiasm in eating was very small live clams that I would split open with a sharp knife. The weight of little cherry stone clam shells presents the clam flesh anchored to a substrat much like their natural feeding on coral polyps. External parasites were a frequent problem. Running both UV and diatomaceous earth filters is highly recommended.

Philip, I’ve found that Four Eyes (C. capistratus) can by routinely trained onto prepared food starting with live California Blackworms; they work nearly 100% of the time as a first food for that species. From there, you can move them onto freeze-dried Tubifex, and once they’ll take Tubifex (which has been soaked in something like Selcon) you can then introduce a broad range of foods that have also been soaked in Selcon…and over time…I’ve had very good luck with C. capistratus eating pellets. Yes, difficult, but overall much easier than the corallivores.

I haven’t had any luck with Pacific Butterflies, but the Atlantic ones will eat chopped-up Aiptasia and California Blackworms with gusto. Spotfins, Bandeds, Foureyes, and Reefs are all quite easy to keep on such a diet for long enough to train them to start eating other things.

See my comments above to Philip. Indeed, the Atlantic butterflies are far easier in the grand scheme than the corallivorous species I’ve been focusing on as of late. I still want to breed C. capistratus though.

Hey, Matt, have you heard about the process of raising larval corallivores, Butterflies and Angels, in such a way as to deny them access to corals while offering them a variety of other things? Hmmm…. actually, I guess there’s no way you missed it, but for other folks I’ll continue. It seems that the fish switch to a coral diet at a certain age, but if no coral is available at that age, they don’t make the switch and just keep being omnivorous. Meyeri, Ornatissimus, Zanclus… there was a company in France several years ago which set about to farm such fish to meet the demand for these dazzling species which are otherwise considered un-keepable. I don’t know how that turned out, though. Do you know of anyone else who has tried this?

Yes, this is a thing Trey! The “tank-raised” pre-settlement and post-larval fishes getting switched onto pellets was a proven concept for dealing with many difficult fish. It’s the main reason why I’m confident that a captive-bred corallivorous butterfly would be orders of magnitude easier to keep than their wild-caught counterparts. That, and my success with captive-bred Harlequin Filefish transitioning straight onto prepared foods like Otohime….another proof of concept. The problem is that people aren’t doing these “tank-raised” fish now…breeder is a more reliable way to get to the end result that we’d like, and for me, that’s what trying to keep the corallivores is all about. I didn’t explain it well enough in my MACNA talk, but all my work wtih corallivores, particularly since about 2016, has been one big “broodstock” project. Gotta keep the fish alive before we can ever hope to breed them.

Hello

Pleas can you tell me what is the food you give to the arabien butterfly ?

Witch one of Repashy food you recommended ?

Aldo