In 1968, Mia Farrow traveled to the foothills of the Himalayas with her sister Prudence to meditate with the guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. She was trying to evade the tabloid superstorm that had erupted around her marriage, at 21, to Frank Sinatra, then 50, and continued through their breakup, almost two years later—Farrow received the divorce papers, with no advance notice, on the set of the movie she was filming at the time, Rosemary’s Baby. “I loved him truly,” she writes about Sinatra in her elegant 1997 memoir, What Falls Away. “But this is also true: it was a bit like an adoption that I had somehow messed up and it was awful when I was returned to the void.” Spirituality had also long been a focusing principle in her life, and she hoped that the Maharishi’s practice of Transcendental Meditation might help her find some peace. “I was not a pediatrician in Southeast Asia, or a Carmelite nun in England,” she writes, mentioning two early aspirations. “I was a lightweight—a Hollywood starlet on the verge of divorce.”

In the decades since, Rosemary’s Baby has become a horror classic, and Farrow has acted in 40-plus more films, including almost every one that Woody Allen made in the ’80s, when they were a couple. Nominated for nine Golden Globes, she’s won twice. She’s had 14 children, four biological and 10 adopted, a fact some consider admirable and others hold up as evidence of an irresponsible savior complex. She has lived through one of the most acrimonious celebrity breakups in the history of celebrity. And in 2000, she was named a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador—she’s made 15 trips to Darfur and Chad to advocate for refugees. People have called her many things, in other words, but at this point, “lightweight” is unlikely to be one of them.

Farrow’s most recent performance was in the 2014 Broadway production of Love Letters (the New York Times described her as “utterly extraordinary”). Now 73, she acts infrequently. “I don’t want to be sitting out in the street wrapped in my Eddie Bauer coat waiting to do a shot at two in the morning wishing I was home,” she says at her ELLE photo shoot this past August, exuding the same blend of magnetism and wide-open sensitivity she projects onscreen, whatever the character, a breeziness undergirded by steel. “I mean, I did that,” she says. “All my life, I worked.”

Farrow landed her first role at 18, in a stage production of The Importance of Being Earnest. The third of seven children, she was born to Hollywood royalty. Her mother was actress Maureen O’Sullivan, who played Jane in the 1930s Tarzan films, and her father was John Farrow, an Academy Award–winning director and screenwriter and also, Farrow writes, a “womanizer of legendary proportions.” When Farrow was young, she and local friends put on street-side shows for the tourist buses that would trawl their Beverly Hills neighborhood. Her memories from that time have a halcyon quality—a pond with darting goldfish, sprinklers she’d run through barefoot. But at age nine, she was diagnosed with polio and spent three weeks in an isolation ward, an experience that left her understanding something of “the unutterable pain of being here on this earth.” Ever since, tragedy has trailed her like a scent. Her oldest brother was killed at 19 in a plane crash, shattering her parents’ unsteady relationship. Not long after, she recalls her father, in a drunken rage, chasing her mother around with a knife. When she was 17, Farrow, in New York with her mother, spent a night avoiding his calls because she didn’t want to tell him that her mother was out with another man. The next morning, she learned he’d died of a heart attack.

Fame, the overwhelming, life-altering kind, came with her second role, in the television series Peyton Place. “I didn’t take to it well,” she says. “You can call it pretty. Call it whatever you want, but in fact it was grotesque. When I see a very young person dealing with sudden fame now, I say a prayer for them that they don’t get lost.”

But none of her early experiences with notoriety could prepare her for the frenzy that greeted her breakup with Allen, which occurred after Farrow discovered explicit Polaroids he had taken of her then college-sophomore daughter, Soon-Yi (Allen and Soon-Yi subsequently married). A few months later, Farrow and Allen were still trying to co-parent the three kids they shared when their seven-year-old daughter, Dylan, accused him of sexual abuse (which Allen denies). A brutal custody battle followed, during which Allen’s camp portrayed Farrow as a vindictive woman and a bad mother.

Her memoir is structured around the losses she’s experienced—“it was through the tragedies that I rebuilt myself each time,” she says—and to read it is to understand how Farrow became a person so keenly aware of the way pain and joy can coexist, of “humanity in its hideousness and its brief quivering beauty,” as she writes. It is to wonder at the way a person’s life—nuanced, imperfect, ever-changing—gets distilled down to a single interlude in the public eye. But it’s also to realize Farrow has intersected with an almost improbable number of notable figures, in pop culture and beyond. Her childhood dog was the grandson of the original Lassie. She was the first person to trim the hair of Liza Minnelli, a childhood friend, into a pixie cut. She had love affairs with both Václav Havel and Philip Roth. She once watched Salvador Dalí throw fistfuls of bills out his hotel window, and Sharon Tate was one of her closest friends. And now this rarefied group also includes her son Ronan, a Pulitzer Prize–winning New Yorker writer whose 2017 reporting on Harvey Weinstein played a pivotal role in prompting the tidal wave of revelations that has top-pled many people in the entertainment industry.

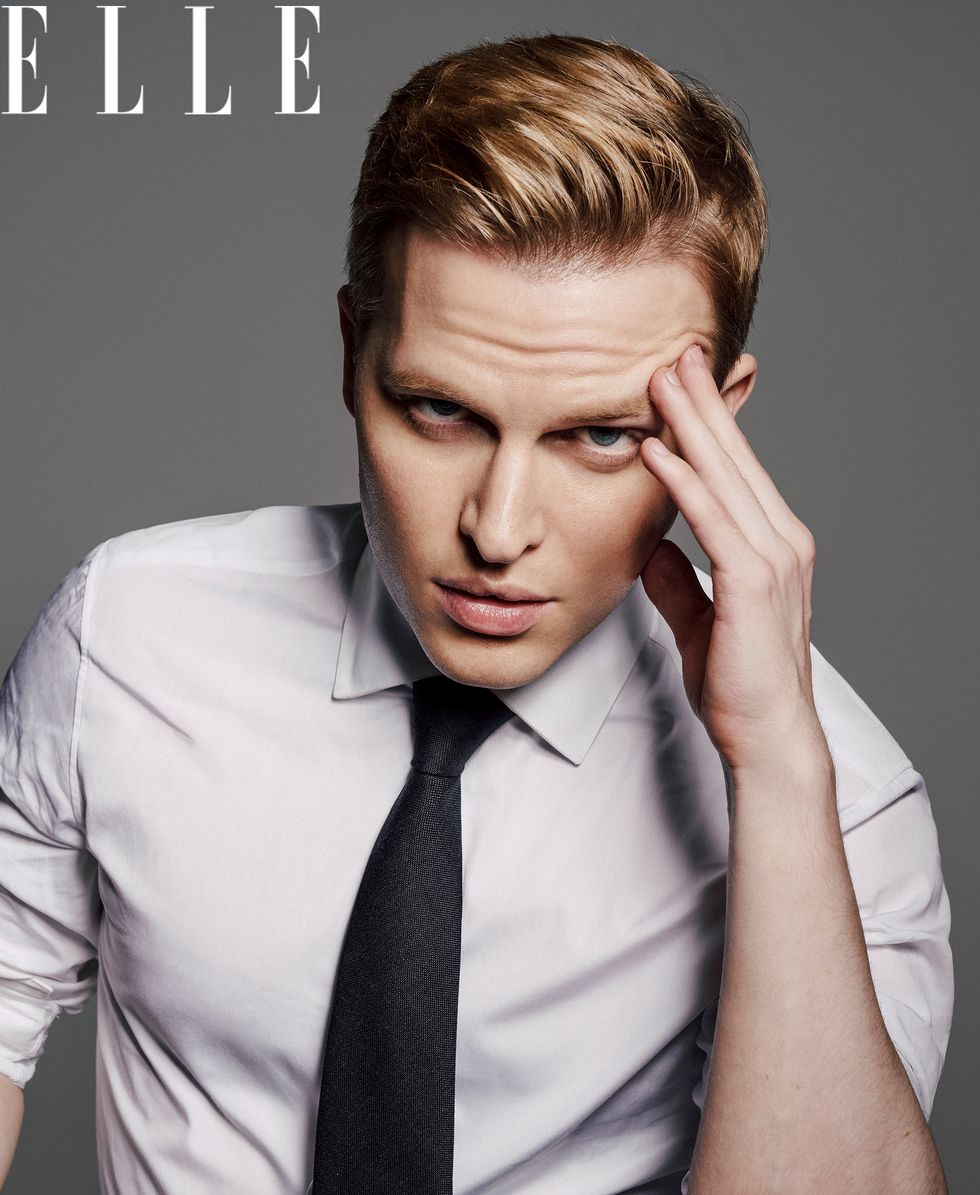

Ronan, who at the photo shoot is self-contained, watchful, and luminous, is careful to separate his family background from his journalism. Though he acknowledges later, by email, “[My mother’s] absolutely one of the many women who were the subject of an old-fashioned smearing and blacklisting campaign. None of it would hold up to one iota of scrutiny today. ‘She’s nuts, she’s jealous’ is an old and thin deflection tactic in child abuse cases. But she was in the crosshairs of that at a time when a certain echelon of a powerful man in Hollywood with the right team of publicists really held all the cards. In retrospect I see the parallels to some of the systems that I’ve reported on.”

The #MeToo movement has also led Farrow to reconsider aspects of her past. “Oh, Lordy, I wish there were tapes,” she says. “The first really awful grope was a very famous head of a studio. I was 17. I was too embarrassed to even tell my mother.” When it comes to her time with Allen, though, “it’s not all white or black,” she says. “Otherwise you’d ask yourself what on earth you’re doing with that person for 10 minutes, let alone for 10 years.” She can rarely mentally file experiences in just one place, she explains. If given the chance, would she work again with Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski, considering he’s guilty of sexual assault? “It’s not in the cards,” she says. “But I don’t think I would.” Yet a few minutes later, when asked to name the film project she found the most creatively engaging, she tells me it was Rosemary’s Baby: “I will say, it’s wonderful working with Roman Polanski.”

At the Maharishi’s compound in Rishikesh, India, by the way, Farrow did find that his practices helped her regain a foothold in the world. But soon the calm of his ashram was shattered by the arrival of the Beatles—photographers scrambled into trees trying to get a shot. In the days that followed, the Beatles wrote “Dear Prudence” for Farrow’s sister. Then, after a private meditation session, the Maharishi made an unwelcome advance on Farrow. “Suddenly I became aware of two surprisingly male, hairy arms going around me,” she writes. She immediately left the ashram. And in keeping with the ways Farrow’s life has twisted through a trivia night’s worth of events, this encounter also set in motion the Beatles’ break with the guru. Their song “Sexy Sadie,” about a woman who made a fool of everyone, was originally titled “Maharishi.”

Farrow now lives in a farmhouse in Connecticut with a pond, chickens, and a garden full of flowers. This is where she settled after the madness with Allen, raising her younger children amid what sounds like (slightly) organized chaos. Ronan, for example, once hatched 27 chicks in his bedroom. “Only when the maggots began to fall from the ceiling did I understand they had to be moved downstairs,” she says. Then raccoons got into the house and massacred them. “Raccoons, you may not know, wash their hands in the toilet.” (The chickens she now has live in a coop outside.)

Ronan, she says, began to speak in full sentences at seven months. “I’d bring him to the market in one of those front pouches, and he would select things—‘No, don’t get the Cheerios with sugar.’ ” He graduated from Bard at 15, with Farrow driving him the three hours round-trip nearly every day. “There was obviously a great deal of pain and turmoil in my childhood, but I also got to see a working single mom spend incredibly long hours being there for each of us,” Ronan writes. “Many of my siblings had complex physical and mental health issues to navigate, and the way she threw herself into years of dealing with that, while still making things fun and imaginative, still kind of bowls me over.”

In recent years, Farrow has experienced more losses. Three of her children have died, and she is estranged from Soon-Yi and a son, Moses, who has accused her of physical abuse (which she denies). She has achieved a measure of anonymity, but this was punctured in 2014 when Dylan published an open letter in the New York Times restating her sexual assault accusations. Ronan followed it with a Hollywood Reporter column stating, “I believe my sister.” “Both of them wrote their pieces without telling me,” Farrow says. “Because for me, it’s the sleeping dog that you don’t want to rouse. But I also understand and deeply respect when my daughter decided she needed to do this.”

In September, after New York magazine published a lengthy and fairly scathing article offering Soon-Yi’s side of the story, Farrow declined to comment. (Dylan and Ronan put out statements condemning the piece, and Dylan also posted a statement from seven of her siblings that read, “None of us ever witnessed anything other than compassionate treatment in our home…. We reject any effort to deflect from Dylan’s allegation by trying to vilify our mom.”) What Farrow had previously told me about Allen is that she had become indifferent: “I reached a place many years ago where I just don’t care about him.”

Instead, she pursues her humanitarian work. She tweets frequently, and while her posts are often horrified missives about politics, in August she tweeted a New York Post story about a drunk man arrested for urinating on a passenger during a flight with the caption, “Did I date this guy?” This sly sense of humor is also what’s on display when I ask about her much-discussed suggestion, in a 2013 Vanity Fair article, that Ronan’s father may have been not Allen but Sinatra. “Will it still fly if I say he was an immaculate conception?” she asks. “It worked for Mary.”

She attends an Episcopal church. She visits with friends. She takes pride in her kids, two of whom live on her property with their families. “I really appreciate all the mundane and beautiful things,” she says. “ ‘Oops, we’re out of Pampers, I’ll go get more.’ It’s fun for me to just live a normal life.”

One thing she was told as a child has proved apt. She was walking with a friend’s father, the actor Charles Boyer, when they discovered a baby bird on the sidewalk. After Boyer gently placed it back into its nest, something about Farrow’s hushed silence, her uncomfortable but awed reverence for the moment they’d shared, prompted him to place his hands on her shoulders. “Your life will be a wonderful one,” he said, “but difficult, I think.”

This article originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of ELLE.