Some thoughts on the Tiananmen Square massacre.

The 1989 massacre of pro-democratic demonstrators continues to resonate throughout recent world history.

Tomorrow, June 4, is the 34th anniversary of the Chinese government's appalling and bloody crackdown on demonstrators in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. This event, which was extremely formative for me personally, even watching it from afar--I was 16 at the time--has had a unique and fascinating resonance through history since that time. As a teacher of history, I've had to teach about the massacre several times in a number of different contexts. As an observer of history and culture in real time, I've watched its meaning and interpretation change over the years. Today it is at once culturally prominent and also curiously obscure. The Chinese government would just as soon everyone forget it, but of course what they think about it is worthy of no serious consideration. Tiananmen Square stands as a unique inflection point in the history of China and the recent history of the West as well. As such, it's worth thinking about.

Even at the time, the spring of 1989, the origins of the Tiananmen movement were mostly opaque in the West. It was sparked by the observance of a handful of Beijing college students of the April 15, 1989 death of Hu Yaobang, the former General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. While in office from 1982 to 1987 Hu tried to thread the tiny needle between being the yes-man lackey to the moldering ancient revolutionary Deng Xiaoping, no longer the official leader of China but still the power behind the throne, and some course of reform of the Communist system that Hu understood needed to happen for the survival of the regime. Hu was cashiered after a previous round of pro-reform protests, especially by China's young people, in 1987 and as a result he was seen as sort of the patron saint of China's youth. When he died of a heart attack, a small band of his supporters showed up in Tiananmen Square, just opposite the Chinese government's walled compound, to demand that they reassess Hu's legacy. Those small demonstrations swelled into a very big one. Soon 100,000 people, most of them in their 20s or even teens, were camped out in Tiananmen Square. This kind of situation was Deng Xiaoping's worst nightmare.

I'll spare you the rest of the history lesson and skip to the end. The protests caused a power struggle within the Chinese leadership between hard-liners, who wanted nothing more than to fire-hose Beijing in the blood of demonstrators, and the reformers--the intellectual progeny of Hu Yaobang--who dared to imagine a China where perhaps Communist rule didn't suck quite so much. As you know, the hard-liners won. The Chinese government from the beginning has played disingenuous games with the numbers of people it killed in the massacre, admitting sheepishly that, well yes, some people were killed when it sent the People's Liberation Army rolling through Tiananmen Square with tanks, but it was only a few hundred. It's a dodge because most of the casualties occurred technically outside the boundaries of Tiananmen Square, on the surrounding streets. Some estimates of the death toll have put it as high as 7,000. The number that seems most likely to me is around 4,000, which is still appalling. That's almost the number of Americans killed in the eight years of the Iraq War. Imagine an entire Iraq War unfolding in one night, in one city.

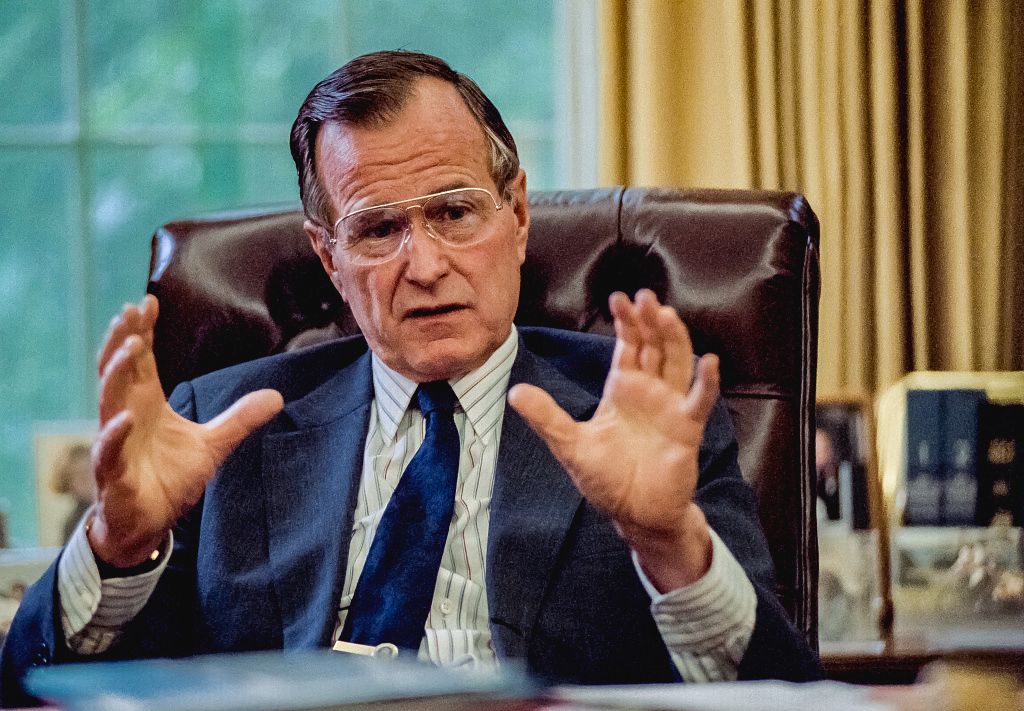

Tiananmen Square was a challenge to the world because by 1989 it was comparatively rare for one of the world's most important governments to conduct such a high-casualty massacre out in the open, on TV screens around the globe. Nineteen-eighty-nine was not the 1950s and Red China was not the rogue state that the West once thought it was, at least before Nixon opened diplomatic relations with them in 1972. It would have been one thing if a third-rate dictatorship, like Iraq or North Korea, committed such an atrocity. Most of the world probably would have shrugged it off. But China was a major emerging power with close and growing economic ties to the rest of the world, rapidly on its way to becoming the globe's first industrial economy. The United States couldn't react to what had happened in Tiananmen Square without affecting a lot of diplomatic, economic, and political irons in the fire that it did not have with the brutal rogue states who usually did this sort of thing. Thus, the massacre proved a headache particularly to the new U.S. President, the first George Bush, who'd been on the job barely five months.

Bush's record as President shows that he was an intelligent man but a remarkably unimaginative and uncreative one, generally poor at understanding the broader implications of the policies he pursued. Nothing demonstrated this fault more starkly than Tiananmen. Failing to appreciate the moral and historical dimensions of the massacre, he erred on the side of token gestures of condemnation of the Chinese government, but assiduously avoided taking any action that he feared would irritate the Beijing commissars, who were notoriously skittish about international discussion of their domestic policies. Bush unfortunately heeded the advice of former President Richard Nixon who warned him to stand firm against the "strange coalition of China-bashers." An outraged House of Representatives, furious at Bush's effectively siding with Deng Xiaoping, passed a sanctions act without a single dissenting vote--a unanimity rarely seen in Congress on anything more consequential than declaring national this-or-that month. Then he set about undermining the sanctions, carving out exceptions by executive order. Biographers of Bush have reported that he was privately relieved on June 5 when the Chinese government cracked down on the demonstrators.

The feckless Bush and the bellicose Nixon were not the only U.S. leaders who were unmoved by what had happened. A year after the event, in 1990, future U.S. President Donald Trump famously remarked in a Playboy interview:

"When the students poured into Tiananmen Square, the Chinese government almost blew it. Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength. Our country is right now perceived as weak... as being spit on by the rest of the world."

Trump carried this sentiment with him into the White House in 2017, coddling not only the Beijing regime, but those of Russia, North Korea, the Philippines and Turkey as well.

The memory of Tiananmen was always real to me, but became even more so during the years (2010-17) when I was in graduate school, working on my Ph.D. in history. At that time (and today also), international students were a significant portion of the University of Oregon's student body and a huge part of its income stream. A majority of those students were from China. Every year on June 4, the anniversary of the massacre, placards or memorials written in English and Chinese would appear in various places on campus. Most of the international students were in their 20s, the same age as many of the students killed in Beijing, and most were probably not even alive yet in 1989 when it happened. Yet it was clear the massacre was important in their own sense of political and cultural identity.

On the other hand, there was, surprisingly, a significant portion of the Chinese international students who had never heard of the Tiananmen Square massacre while growing up in China and didn't learn of it until they went to school in the U.S. I know this because I TA'd for a class on modern Chinese history, about 85% of which consisted of Chinese international students. One day I showed them the famous image of "Tank Man" and asked how many of them had ever seen the image before. Less than half the class raised their hands. The Chinese government and school system has evidently made an effort to erase the massacre from their own history. I had to ponder the irony of being an American teaching Chinese people in English about an event that happened in the recent history of their country.

Deng Xiaoping, the person most directly responsible for the massacre, died in 1997. Most of Deng's henchmen who collaborated with him, such as the odious Li Peng, are also dead. The Tiananmen Square "incident," as the Chinese call it, is now a generation in the past and no doubt there are more people in positions of power, both in China and the West, who would just as soon treat it as ancient history incapable of influencing the present. That would be a mistake. Someday, long after the Communist dynasty of China is gone, there will be a memorial in Tiananmen Square to those who died that terrible night. Historical memory has a way of outliving the will of tyrants.

The Value Proposition

Why should you be reading this blog, or receiving it as a newsletter? This is why.

☕ If you appreciate what I do, buy me a virtual coffee from time-to-time to support my work. I know it seems small, but it truly helps.

📖 You could also buy my newest book.

🎓 Like learning? Find out what courses I’m currently offering at my website.

📽 More the visual type? Here is my YouTube channel with tons of free history videos.

Comments ()