Autograph manuscript signed: Julius Robert Mayer:Die Entdeckung des Gesetzes der Erhaltung der Energie

Publisher Information: 1965.

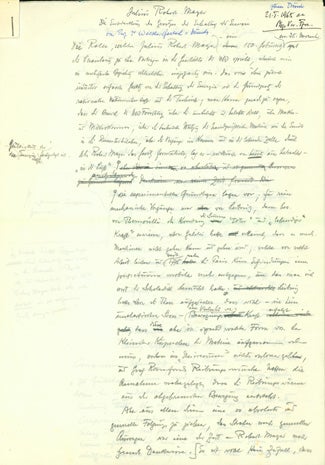

Gerlach, Walther (1889-1979). Julius Robert Mayer: Die Entdeckung der Erhaltung der Energie. Autograph Manuscript Draft, signed. 4-1/3 pp., written in pencil and ballpoint pen on rectos of 5 sheets; sheets stapled together in upper left corner. Munich, January 21, 1965. 300 x 212 mm. Creased where previously folded, very slight wear and soiling. Very good. English translation included.

Draft of Gerlach's lecture commemorating the 150th anniversary of the birth of Julius Robert Mayer, one of the founders of the principle of the conservation of energy-the first law of thermodynamics. Gerlach, "contributed to many experimental topics, especially the ones connected with radiation and quantum theory (e.g. together with Alice Golsen, he determined the pressure of light quantitatively); he made important contributions to the development of modern methods of chemical spectral analysis, the physics of the (technical) magnetization curve, and measurements on artificial and natural radioactivity" (Mehra & Rechenberg, I, p. 436). He is best known as one of the discoverers of the Stern-Gerlach effect (1922), by which Otto Stern and Gerlach demonstrated the empirical validity of Sommerfeld's spatial quantization; i.e., the discrete orientation in space of electronic orbits. The effect is created by passing an atomic beam of silver atoms through a magnetic field of strong inhomogeneity, which splits the silver beam into two separate beams. "This result then proved space quantization as well as once again confirming the existence of stationery states. However, it also went far beyond the Bohr-Sommerfeld theory, as Einstein and Paul Ehrenfest demonstrated by their calculation of the time needed by the silver atoms to be oriented in the two directions: they estimated a time for the (classical) magnetic interaction of 1011 s, in contrast to the observation-which gave a time of less than 10-4 s. Thus one of the bases of the existing atomic theory broke down" (Twentieth Century Physics I, pp. 164-65).

The energy-conservation principle was arrived at more or less simultaneously in the mid-19th century by a number of scientists, the most important being Helmholtz, Joule and Mayer, but Mayer was the first, as Helmholtz acknowledged, to articulate a general law of energy conservation. Gerlach's lecture gives a brief history of Mayer's discovery and its reception:

The law of conservation of energy, first understood empirically by [Mayer], is the fundamental principle of rational natural science and technology. It can be stated that the entire area of natural science research is governed by the validity of the energy law throughout the inanimate and animate world, through the macro- and micro-cosmos, through the technical utilization of apparent matter such as the insight into elementary particles, through cosmic processes, and within living cells. . . .

It is thus no coincidence that Mayer as well as Helmholtz, who established the energy theorem five years after [Mayer] in his writings on the conservation of force, making use of the same considerations, but with different motivation, came not from physics but from physiology. In it the picture of a life force dominated, even though it was perceived as being unsatisfactory, which was supposed to control processes in the organic realm, as mechanical force did in inanimate nature. After unfavorable experiences with "natural philosophy", that blurry mixture, physicists rejected generalizations and extrapolations for fear of allowing it [natural philosophy] back in again. Therefore, Poggendorff also did not print Helmholtz, in the Annalen der Physik, and Helmholtz said in 1854 that Robert Mayer was the first one who had dared to state such a general law. . . .

In 1842 Mayer calculated the mechanical equivalent of heat from the Dulong-Petit experiments, and with it the low efficiency of the steam engine, whose principle of operation he was the first to explain correctly through the consumption of heat as the equivalent of the work produced, . . .

Mayer's accomplishment was not recognized for a long time. Helmholtz, and Joule as well, rejected his arguments, unjustly criticized the calculation of the heat, and unqualified individuals ridiculed him in public. Only Clausius quoted Mayer's first work and the equivalent as a first principle of his thermodynamics in 1850. But at that time Mayer became seriously mentally ill. Only now did the energy law establish itself in the thought process of natural science. The Basel chemist Schoenbein referred to Mayer's accomplishment in 1858, and Justus Liebig praised him as the father of the greatest discovery of the century. A rapid sequence of the highest honors then followed.

How Robert Mayer arrived at his idea-some kind of a brainstorm on his trip to Surabaya in the summer of 1840-and even more how the self-taught physicist found the decisive experiments in the literature that were needed for his new concept, how he properly described the steam engine quantitatively, against all [prevailing] opinions-all this belongs to the mysteries about which Johannes Kepler said: "It seems to me that the paths by which men come to understand heavenly things are almost as remarkable as the nature of these things themselves."

Offered with Gerlach's manuscript is a copy of Alwin Mittasch's Kraft-Leben-Geist: Eine Lese aus Robert Mayers Schriften (1942), published to commemorate the centennial of Mayer's discovery of the law of energy conservation.

Book Id: 32980Price: $2,250.00