Silvio Berlusconi, a three-time Italian prime minister (from May to December 1994, from 2001 to 2006 and from 2008 to 2011) died on June 12, at the age of 86. He was a member of parliament from 1994 to 2013 and from the fall of 2022 until his death, and led the Italian right, whose factions he successfully managed to unite for two decades. Simultaneously, he was a successful media entrepreneur and owned the emblematic AC Milan football club.

In addition to holding the title of the richest man in Italy on several occasions, he was the president of the Council who has spent the longest time in power since the birth of the Italian Republic: exactly 3,340 days. But despite his longevity, his undeniable sense of tactics and his talents as a communicator, his work in government was marked by a series of private and financial scandals and by a relative weakness – a consequence of his casual and pleasure-seeking temperament, his conflicts of interest and deals made with political forces with sometimes conflicting ideologies. His demonstrative friendship with Vladimir Putin, which he never denied despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, cast a shadow on his image as an Atlanticist and moderate conservative. It will be interesting to see what history will remember Berlusconi for, once the dust settles from the Italian news that he saturated in all its sections (finance, business, scandals, sports and politics).

Born on September 29, 1936, Silvio Berlusconi was the eldest child of a middle-class Lombard family. His father, Luigi, was an employee of the Rasini bank, of which he would become a director; his mother, Rosa Bossi, was a housewife. From their union two more children were born: Maria Antonietta and Paolo. At the age of 12, Silvio entered the Sant'Ambrogio College in Milan, led by Salesians.

According to the legend and the accounts of his childhood friends, he displayed solid abilities in Greek and Latin and already showed strong business sense. Eager to help his classmates, he offered to do their homework for them in exchange for a few lire. But he made a point of returning their money if the grade they obtained was not up to their expectations. Berlusconi also prided himself on having undertaken two years of studies at the Sorbonne after his maturita (high school diploma), an experience from which he would retain some knowledge of French and a vast knowledge of the repertoire of singers Charles Trenet and Charles Aznavour.

Real estate investments

He graduated with a law degree from the University of Milan in 1961, with a thesis on advertising contracts. At the same time, he indulged his passion for song by joining a group, The Four Doctors, which also included Fedele Confalonieri. Throughout his life, Confalonieri supported Berlusconi's entrepreneurial ventures. He managed the business while Berlusconi was in power. The two men also acted as entertainers on Mediterranean cruises. All events in this biography were to be amply dramatized and illustrated with period photos when he published Una storia italiana ("An Italian story" not translated), a magnified account of his life, with which he flooded the letterboxes of Italians during the election campaign of 2001. But we are not there yet.

In the 1960s, Milan symbolized the Italian economic boom. An estimated 600,000 "immigrants" from the south and the Veneto region came to the Lombardy capital in search of work. They needed to be provided with a roof over their heads. The city was bristling with cranes, concrete mixers were in full swing and new neighborhoods were springing up.

Berlusconi was quick to see the benefits (and the profits) that he could draw from the rush. He undertook his first real estate operation by building a group of low-cost houses. The plot alone was worth 180 million lire. He only had 10 million lire at his disposal. Who financed the construction? The question would always accompany the consolidation and diversification of his empire. In this particular case, it is likely that the Rasini bank, of which Luigi Berlusconi became director in 1957, was the guarantor.

Other theories maintain that the Mafia, which also followed the migration from the south to the north of the peninsula, deliberately bet on his success. Others have evoked the obscure role of Michele Sindona, the Vatican and Cosa Nostra's secret banker, as if Berlusconi's life reflected all the unsolved enigmas of contemporary Italy.

Smooth-talk and seduction

That first experience was followed by the construction of a complex with 1,000 apartments and then, in the early 1970s, by the building of Milano 2, the first new urban development in Italy. Its residents found everything they desired: a spacious and bright apartment, a garage for their car, a supermarket, schools, a hospital and sports grounds. Always a trendsetter, Berlusconi introduced off-plan sales, a dream on paper that he made sure, thanks to his gift of gab and good manners, would become a reality in the eyes of his future buyers. He summed up his own seduction strategy: "I am convex with concave people and vice versa."

To accomplish that project, Berlusconi created the company Edilnord with partners (bankers, businessmen, lawyers) whose pedigrees were, if not shady, at least mysterious. This first company, whose name can be found in the various lawsuits that marked his career, was followed by many others, until the birth of Fininvest in 1974. This holding company controlled all his business activities. In addition to the name of Confalonieri in the command structure of those diverse companies, there's also that of another friend from his youth: Marcello Dell'Utri, who served a four-year jail sentence between 2014 and 2018 for "complicity in Mafia association." It was also in the 1960s that he met Carla Elvira Lucia Dall'Oglio, whom he married in 1965 and divorced in 1985. Two children marked this marriage: Marina, born in 1966, and, three years later, Pier Silvio.

His success was crowned by the title of "Knight of the Order of Merit of Labor"– which earned him the nickname "Cavaliere" – awarded by President of the Republic Giovanni Leone in 1977. But Berlusconi had already abandoned concrete to take an interest in another industry: the press and television, whose monopoly was abandoned by the state in 1976. In 1979, he became the majority shareholder of the daily Il Giornale.

Network of influence in all walks of life

Hundreds of small TV stations were created. The "king of concrete," who controlled Telemilano, proposed to unite them under a single banner, Canale 5. Thanks to a tailor-made law on the concentration of media, other channels, Rete 4 and Italia 1, were added to this offer, which quickly became equal in terms of audience size to the public channels of the RAI. The empire expanded internationally with the launch of La Cinq in France in 1986 and Tele 5 in Germany and Spain.

He also acquired the Mondadori publishing house in 1990 under the nose of Carlo De Benedetti and with the complicity of a corrupt magistrate. The group also diversified into banking, insurance, financial products and distribution. The icing on the cake was his 1986 purchase of Associazione Calcio Milan, the AC Milan football club, with which he won eight Italian championships and five European trophies.

Such a rise would of course be impossible without important political support. Berlusconi could count on the friendship and collaboration of Bettino Craxi, the strongman of Milan and future Socialist president of the council. They became close in the mid-1970s. It would also be impossible without a solid network of influences in all circles. Italy at that time was plagued by the political violence of the anni di piombo ("the years of lead") and threatened by the rise of the Communist Party. The country was a geopolitical battleground between the West and the East.

Although he was hardly bothered by the investigations of the Mani pulite ("Clean Hands") operation into the vast network of corruption that led to the demise of the Christian Democracy and the Socialist Party, Berlusconi joined the influential Masonic lodge Propaganda Due (P2), founded by Licio Gelli, an avowed admirer of Mussolini. The secret society was committed to saving Italy from communism, even if it meant sowing chaos in order to establish a strong government. Berlusconi rubbed shoulders with former ministers, businessmen and rogue secret service officers.

Comfortable parliamentary immunity

"Italy is the country I love." With these words, Berlusconi appeared on all his television channels on January 26, 1994, to announce his intention to launch a campaign for the 1994 legislative elections. "I refuse to live in a dictatorship governed by immature forces and by men linked to a politically and economically bankrupt past."

Two opposing views arose: his own, in which he claimed his selflessness and his sole desire to serve the country and save it from communism. And that of his opponents, who maintained that this famous discesa in campo ("descent into the field") was dictated by fear of seeing judges poke their noses into his empire, which was heavily in debt at the time. What better way to protect himself than with parliamentary immunity? How better to protect oneself from investigations than by dictating the laws? Of all of Berlusconi's political career, the birth of Forza Italia ("Go Italy"), the party that enabled him to win the election and become president of the Council for the first time, was the most groundbreaking milestone, a textbook case for political science courses.

Berlusconi – who got married again to Veronica Lario, a former minor stage actress with whom he had three more children – saw politics as a business. So, it was within one of his companies, Publitalia, that the idea of forming a new party took shape. The time was right: the political class had been wiped out by the Tangentopoli affair (a vast network of financing and corruption), and Italians were ready to be won over by novelty. His success as an entrepreneur and the success of AC Milan were guarantees of his abilities. The power of his media empire enabled him to control public relations, and finally, his fortune allowed him to run the most lavish campaign.

The first leaders of Forza Italia were all, with a few exceptions, Fininvest executives, Cavaliere's lawyers and employees of his TV stations: Men who were all the more loyal because they were salaried. Added to this entrepreneurial vision of politics was a winning strategy dictated by the majority voting system. Without taking into account their differences, which were fundamental, he teamed up with the Northern League, which demanded autonomy for northern Italy, and the MSI (post-fascist), which, on the contrary, advocated a strong, centralized state and was favored by voters in the south.

The promise of a 'liberal revolution'

On May 10, 1994, Berlusconi was appointed president of the Council on the promise of leading "a liberal revolution." The experience was short-lived. In December, the Northern League withdrew its support. At the time, Berlusconi was suspected of having links to the Mafia, which would have graciously accompanied both his success as an entrepreneur and as a politician. Didn't he host the mafioso Vittorio Mangano in his villa in Arcore in the fictitious role of a groom, at the price of what secret agreement? Berlusconi maintained that the presence of this man allowed him to protect himself from the threats of Cosa Nostra against himself and his family. Despite his denials, he was indicted and the president of the Republic, Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, appointed Economy Minister Lamberto Dini to replace him.

Back in opposition, he did not admit defeat. As the left took over the Chigi Palace and quickly fell into unpopularity, he ran again at the head of the same right-wing coalition called La Casa delle Liberta ("The House of Liberties") in the 2001 elections, which he won. He was one of the few Italian heads of government to complete his term in 2006. However, he was defeated again by Romano Prodi in the same year. Divided, the center left was unable to stay in power for more than two years.

A new election brought Berlusconi back to power in 2008. The coalition that supported him (Forza Italia, Northern League and National Alliance) was the same, although this time it was called Il Popolo della liberta ("the People of Freedom"), the outline of a single right-wing party, which mirrored the creation of the center-left Democratic Party a few months earlier. The slogans were also the same: fight against the communists (even if the PCI had folded in 1991), against the "red" magistrates who were working against him, liberalization of business and lower taxes.

Lucrative personal business deals

While his policies’ effects on Italy, which was mired in sluggish growth and later in recession, were uncertain, the same cannot be said for his personal business affairs. Consistently, he denied that there could be a conflict of interest between his entrepreneurial activity and his position as president of the Council, but he always made sure to exercise the latter role to the benefit of the former. His companies never performed better than when he was in power. Under his leadership, the government decriminalized false accounting and shortened the statute of limitations for some of the financial and corruption offenses of which he was accused. The TV channels of the Mediaset group posted record advertising revenues, while he reined in the management of the RAI public broadcaster. In parallel, inheritance taxes were reduced, to the point of almost disappearing

The opposition calculated that he enacted 21 "ad personam" laws allowing him to walk away from the 30 or so lawsuits that were filed against him without causing him any damage, apart from having to sustain an army of expensive lawyers. His privatization of power was illustrated by his choice of residence in Rome, on the piano nobile of the Palazzo Grazioli (1,000 square meters rented in the center of Rome), where private life and public activities were mixed. He spent only one night in the official residence, the Palazzo Chigi.

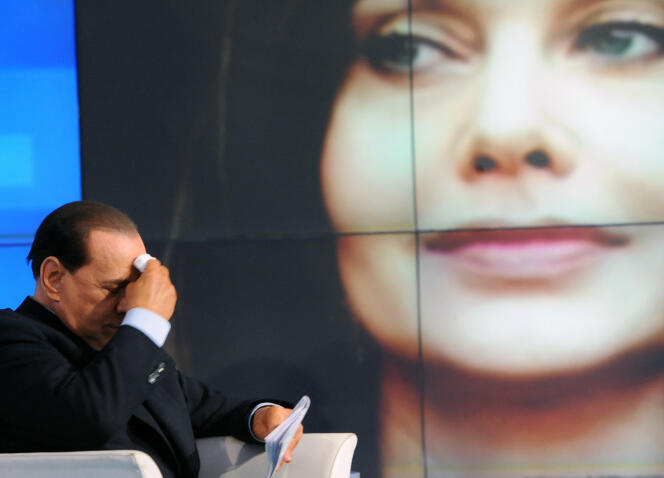

What words can describe Berlusconi's last term in office? Baroque? Truncated? How can it be explained that the Italians entrusted him with the reins of the country once again, when he had already proven his incompetence and his lack of interest in public affairs? Was it a form of latent anarchism that made them prefer a caricature of power to the theoretical majesty of its exercise? In the spring of 2009, when new scandal emerged about Berlusconi courting Noemi Letizia, an underage girl from Naples, the tolerance of many Italian for their leader’s antics was transformed into a feeling of shame and even disgust.

Prostitution network

The news was immediately followed by a scathing declaration from Berlusconi's wife Lario in the newspaper La Repubblica. Not only did she announce that she was filing for divorce, but she also asked her husband's friends to protect him from his unquenchable sexual appetite, which even his fragile health (prostate cancer in 1997, pacemaker insertion in 2006) could not abate. In vain. A few months later, Patrizia D'Addario, a woman from Puglia, came into the picture and revealed that sex parties were regularly organized at the Palazzo Grazioli and at the Villa San Martino, in the suburbs of Milan.

As Italy sank into the longest recession of its history, Berlusconi plunged headfirst into lust. Piece by piece, the system built to satisfy his desires was revealed. A new scandal, named after "Ruby", the nickname of a young girl that Berlusconi tried to present as the niece of former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, revealed a prostitution network organized by a former regional councilor, a former TV news presenter and Berlusconi’s personal accountant. Dozens of girls were fed, lodged and paid to serve the Cavaliere's desires and keep quiet.

The noise from these scandals was considerable, not only in Italy. The country and its leader lost what little credit they had left on the international stage. Berlusconi, who had always been able to capture the mood of the Italian people without being a visionary, claimed that his country was doing well and that "restaurants and planes were full," while debt was soaring. Secretly, the president of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, was preparing the next phase. On November 12, 2011, following a banal vote in the Chamber of Deputies in which the government was outvoted, Berlusconi submitted his resignation. He was replaced by Mario Monti.

Community service

A long decline began. Berlusconi argued that he was a "victim," but no one seemed to believe him, except for those close to him. Charged with "prostitution of a minor," he was first heavily sentenced, and then released on appeal. But it was another case, concerning tax fraud, that finally knocked him out of the political game. In 2012, he was sentenced to four years in prison (the sentence was eventually reduced to one year) and banned from running for public office for six years.

Given his age, the majority of the sentence was commuted to "community service," which he performed in an old people's home in the suburbs of Milan. The Senate, where he was elected in 2013, revocated all his mandates until 2019. Berlusconi, once again, cried conspiracy. From then on, he devoted most of his energy to avoiding the emergence of a real political successor. From 2014, the time of scissions began. Influential figures such as lawmakers Raffaele Fitto, Angelino Alfano and Denis Verdini left Forza Italia to found small centrist parties. Each time they left, they weakened Berlusconi’s influence in Parliament, while considerably reducing the pool of talent at his disposal.

It was not until 2019, with his physical condition forcing him to limit his public appearances, that he finally appointed one of his last strong supporters, former president of the European Parliament Antonio Tajani, as the operational leader of Forza Italia. Tajani tried to take as little initiative as possible, and did not miss any opportunity to remind people of his unconditional loyalty.

In the ballot box, Forza Italia's gradual decline worsened. In the general elections of March 4, 2018, for which Berlusconi had attempted a comeback as the savior of the right, his party obtained only 14% of the vote and was outpaced by more than 3 points by Matteo Salvini's Lega (far right). The latter was able to take advantage of the vacuum created by the weakening of his opponent to conduct a very effective campaign based on the rejection of Europe and migrants. In a political landscape marked by the radicalization of the right and the emergence, alongside Salvini, of a new post-fascist formation, Fratelli d'Italia, which obtained 26% of the vote in the autumn 2022 elections, Berlusconi’s right has become an auxiliary force, peaking at 8% of the vote and limited to 45 deputies and 18 senators.

On the business side, the last years of his life seem to have been marked by an obsession with consolidating his legacy by maintaining unity between his five children. This despite the notorious disagreements between the two eldest children, from his union with Dall'Oglio, who were long involved in the management of the group, and the three children conceived with Lario, who were born two decades later, in the 1980s.

In the spring of 2017, Berlusconi parted ways with AC Milan, selling it to mysterious Chinese investors. Over time, the club had lost much of its glory and had become was making losses financially. In 2016, Berlusconi began talks with French businessman Vincent Bolloré, the owner of Vivendi, to forge an alliance that would consolidate his media empire, but relations between the two men deteriorated as the Frenchman increased his stake in the Mediaset group to almost 30%, causing a legal dispute to erupt between them. Bolloré took a challenge all the way to the European Commission in Brussels to contestthe tailor-made laws that protected his rival from any risk of losing control of his group.

Invigorated for a time by this fight, in which he once again used his political influence to serve his private affairs, the former prime minister generally struggled to conceal his inevitable weakening. After breaking up with his partner Francesca Pasquale in 2020, he offered himself the luxury of one last romance with Marta Fascina, a lawmaker for Forza Italia and former model aged 30. During the last months of his life, she became a key go-between for all those who sought to reach the aging Cavaliere, who was ailing from long Covid and multiple heart attacks. Condemned to ever shorter public appearances, the former prime minister left the Grazioli Palace in central Rome, and spent most of his time in his villa in Arcore. His entourage convinced him one last time, in February 2022, to try his luck to be elected as president of the Republic, but his candidacy was not successful.

A few weeks later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, instigated by a friend, Vladimir Putin, to whom he would never cease to express his friendship, completed the marginalization of the Cavaliere and his party, which was increasingly isolated in the European Parliament. By declaring in February 2023 that the Russian offensive of February 24, 2022, had been prompted by "attacks" from Ukraine and blaming the war on President Zelensky, Berlusconi caused his ally Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni much embarrassment, and forced her to emphasize her "firm support" for Ukraine. But according to most observers, this final provocation by the former leader of the right was not so much evidence of a political disagreement as it was of the weakening of a very old man, who had lost all grip on reality for months.