Ota Benga (Mbye Otabenga)

By Emily Kubota, Curator

CONTENT AND TRIGGER WARNINGS: This article contains historical terms, phrases, and images that may be upsetting to modern viewers. These include offensive and dehumanizing references to race, ethnicity, and nationality. It also contains a description of a suicide and may not be appropriate for everyone.

Ota Benga, courtesy of the Library of Congress

St. Louis World’s Fair, 1904, courtesy of the Library of Congress

Ota Benga was born in the Congo in central Africa sometime around 1885. He was exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair (“Louisiana Purchase Exhibition”) in 1904 after being captured from his homeland. His tribe, the Batwa or Mbuti people, and his family were murdered by the violent Force Publique, the military force of the Belgian government, which sought to exploit local rubber and ivory resources. After being sold by slave traders, he ended up in the hands of businessman and white-supremacist Samuel Phillips Verner, who was under contract to bring back “pygmies” for exhibition at the St. Louis World Fair. In an article later written by Verner, titled “An Untold Chapter of My Adventures While Hunting Pygmies in Africa,” he bragged that he was able to obtain Ota Benga by giving his captors only $5 worth of goods. Benga and eight other men were taken to America by Verner for the purposes of display and exploitation.

Once they arrived at the fair, Benga and four of the other captives were placed on exhibition along with other Indigenous people of the Americas and Asia. Visitors were eager to see Ota Benga’s teeth, which had been filed ritualistically into sharp points, and to see his small stature. He was advertised as a “cannibal,” and the group was expected to behave savagely. As the men were prisoners, they were gawked at, burned with cigars, and taunted. At night they were not given adequate clothing or shelter to protect them from the low temperatures. When the public was not around, the men were measured and studied as scientific specimens by academics of the time who were trying to prove the supremacy of people of European descent.

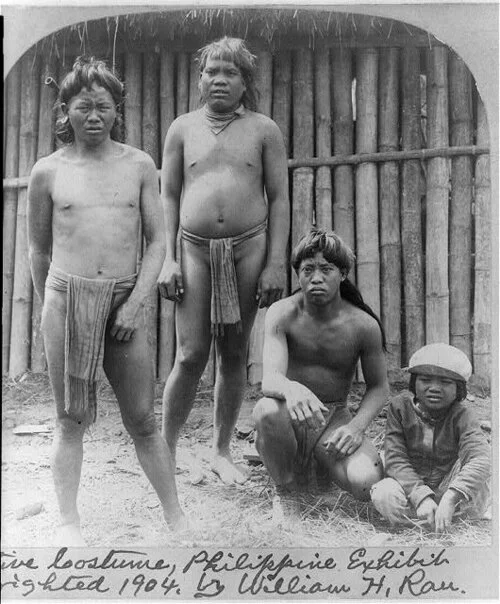

Indigenous men from the Philippines exhibited at the St. Louis World Fair, 1904. Ota Benga and his companions from Africa would have been exhibited in a similar fashion, with their traditional clothing and housing structures. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

After the fair ended, Benga briefly got the chance to return to Africa. His tribe and family had been murdered years earlier, and Benga was forced to live with the Batwa people. He remarried, but when his new wife died of a snake bite, Benga agreed to return to America. The situation only got worse when he was placed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City upon his return to the United States. Again, he was not able to leave the premises and was objectified by audiences. His next destination was the Bronx Zoo in 1906. That September, he was placed on exhibit in the “Monkey House” with an orangutan. The sign on his cage read:

The African Pygmy, Ota Benga

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches

Weight 103 pound. Brought from the Kasai River,

Congo Free State, South Central Africa,

By Dr Samuel P Verner.

Exhibited each afternoon during September

He was verbally and physically harassed by indifferent white visitors numbering around 500 at a time. When he fought back, he was labelled as mischievous and violent, which only added to his reputation as a “savage.” Eventually Benga was free to roam the grounds, but was chased and abused by crowds that constantly followed him.

His exhibition was supported by anthropologists and was touted as an educational tool. Some believed him to be the missing link and encouraged his exploitation under the guise of science. As more people viewed him on display, the African American community was outraged. Prominent Black leaders pleaded with the mayor and with zoological societies to intervene. So much attention was drawn to Benga that even the New York Times published an editorial about his display. Their opinion firmly came down on the side of white supremacists:

“We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter… Ota Benga, according to our information, is a normal specimen of his race or tribe, with a brain as much developed as are those of its other members. Whether they are held to be illustrations of arrested development, and really closer to the anthropoid apes than the other African savages, or whether they are viewed as the degenerate descendants of ordinary negroes, they are of equal interest to the student of ethnology, and can be studied with profit… Pygmies are very low in the human scale…”

Hayes Hall, Virginia Theological Seminary & College, Courtesy of Jackson Davis Collection of African American Photographs, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Eventually, African American clergymen were able to petition for his release. In late September 1906, after 20 days of exhibition, the zoo quietly removed Benga from display. He was released into the custody of Rev. James H. Gordon, who placed him in an orphanage as a grown man in his twenties. Finally in 1910, Benga was brought to Lynchburg, Virginia, where his teeth were capped, he was given European-American clothing, and he attended school at the Virginia Theological Seminary and College (known today as Virginia University of Lynchburg). A family associated with the Seminary brought him into their home, and he was tutored by local poet and librarian Anne Spencer. Here he found camaraderie with the Black community and enjoyed teaching young boys how to hunt and fish.

Ota Benga always dreamed of returning to the Congo but realized it was not possible when World War I began in 1914. His loneliness became unbearable, and those closest to him began to see a shift in his demeanor. On the night of March 20, 1916, Benga removed the caps from his teeth and built a ceremonial fire. His young friends watched as he danced and chanted around the flames in a ritual unknown to them. Later that night Benga ended his own life with a pistol shot through the heart. He was only about 30 years old. His body was interred at Old City Cemetery, but may have been moved to White Rock Cemetery at a later date. The exact location of his gravesite remains unknown, but a marker surrounds what is potentially his plot.

In August of 2021, Congolese National Assembly representative, the Hon. Christelle Vuanga and associate Mme. Laetitia Basondwa paid a visit to White Rock Cemetery. They stopped at the believed resting place of Ota Benga and spoke to him in his native language. Benga’s story lives on both in Lynchburg, and in his native homeland of the Congo.

Hon. Christelle Vuanga and Mme. Laetitia Basondwa from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in White Rock Cemetry, believed to be the final resting place of Ota Benga. Photo taken by Museum Director Ted Delaney