Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

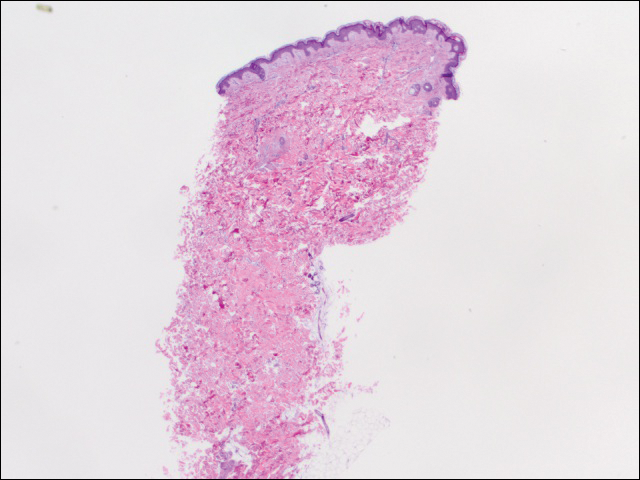

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.