Sex, Class and Queer Expression: Understanding David Hockney's Fascination With Pools

As Hockney becomes the most expensive living artist in history, we deep-dive into his favourite motif

Adam Heardman / MutualArt

Nov 16, 2018

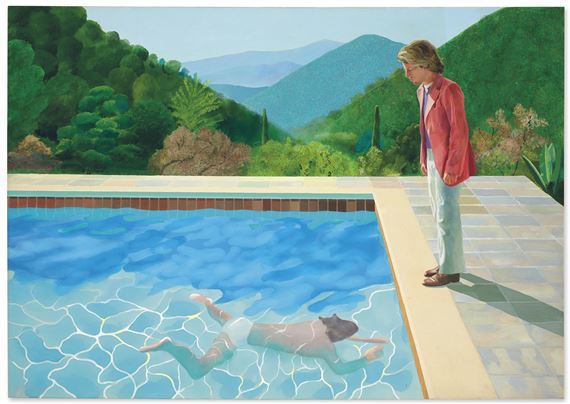

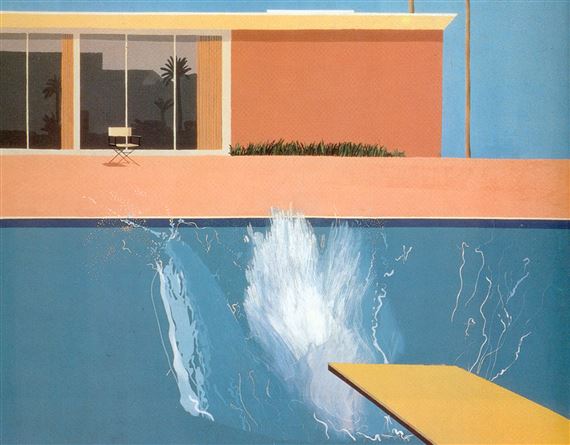

As Portrait of An Artist (Pool With Two Figures) becomes the most expensive work by a living artist ever sold, we explore the significance of the modern master’s favourite motif.

David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) (1972)

Hockney supposedly fell in love with swimming pools from a height. As his first flight to Los Angeles came in over the city in 1964 the pools' surfaces blinked beneath him, reflecting the white California light, adding their aquamarine to the green-grey urban sprawl.

The painter’s own retelling of the encounter is characteristically understated. “I looked down to see blue swimming pools all over”, he told Diane Hanson in 2009, “and I realised that a swimming pool in England would have been a luxury, whereas here they are not, because of the climate.”

This is, bear in mind, the same Hockney who once said of his own art, “it’s over-rated. My art isn’t as good as some people think it is”. Less through humility than through anti-establishment irreverence, Hockney’s never one to be needlessly grandiose. He’s an iconoclasm of calm. So it’s probable that this deadpan observation about pools in the US versus pools in the UK, this small-talk invocation of the weather, is simply the Bradford-born artist’s own way of communicating what was actually, on the evidence of his paintings, a profound and career-changing revelation.

Despite denying that he was himself a ‘pop-artist’, Hockney borrowed from pop the practice of bringing complexity to the surface, collapsing the vision-field of a painting and getting all of the information right up into the foreground. Just because something’s shallow, doesn’t mean it isn’t complex. ‘Deep’ has always been a metaphor anyway. Like Hockney’s pools, his statement is all surface and all depth.

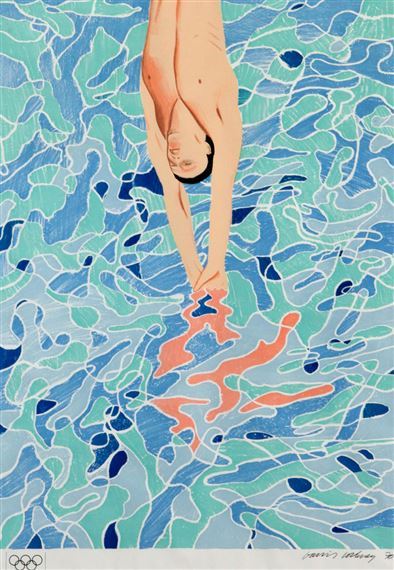

David Hockney's poster design for the Munich Olympic Games (1972)

Beneath Hockney’s conversational tone lie important, complex points about what he could achieve, in his life and his art, by moving from 1960s Great Britain to 1960s Los Angeles. Homosexuality was illegal in the UK until 1967, and as a self-confessed ‘homosexual propagandist’, David Hockney felt the lack of expressive queer space to be stifling, both personally and professionally. He was drawn to the potential of creative outlets like the beefcake magazines of LA pulp literature as queered zones of image making.

But the better symbol for those patterns of tension and release, those crossovers between performative and domestic kitsch, those peaks and troughs of erotic interrelations which were central to Hockney’s vision, turned out to be those glinting private pools he spied from the aeroplane.

To understand why they caught his eye so powerfully, one must appreciate how much a private, outdoor Los Angeles pool differs symbolically from the swimming pools of the UK. Hockney’s point in the interview with Diane Hanson stands - in Britain, only the very wealthiest have swimming pools in or on their property. It’s a sort of ‘new money’ status-symbol on par with long driveways, SUVs, or (ironically) original artworks.

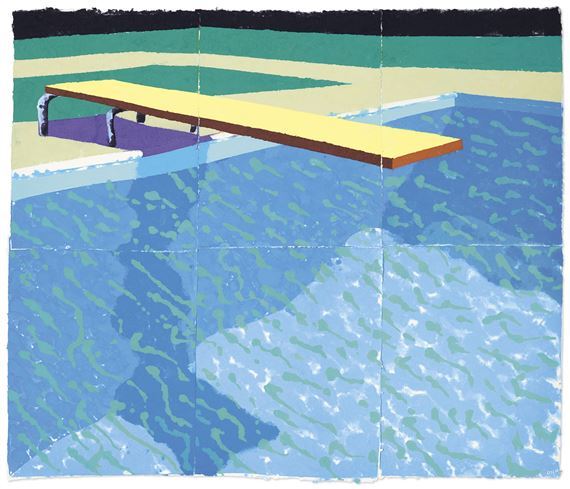

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash (1967)

For the majority of UK citizens, and certainly for a working-class Northerner like Hockney, early experiences of pools would likely be through the local swimming baths. This is a public, municipal space. The psychosexual complexities and womb-ish, Freudian implications of nakedness and liquid are played out amongst the community, under the sometimes judgemental glare of your neighbours and peers.

George Townsend, who is researching a PhD in bathing culture at Birkbeck, University of London, explains: “Crucial to depictions of the bathing scene is not just leisure but what Kristin Ross has termed ‘communal luxury’ – a sensual sociality, anchored in a proliferation of bodies opened up to air and light, water, gaze and, perhaps most important of all, bodily connection.”

It’s easy to imagine what such an atmosphere would have meant to a young Hockney. It would simultaneously have offered early pubescent experiences of other bodies, whilst also operating as an extension of staunch community morals, particularly institutional homophobia. It’s no exaggeration to suggest that, for generations of modern Britons, the swimming baths represent a crucial formative zone of both sexual expression and sexual repression.

Water, in its simultaneous fluidity and tension, its co-habitation of ‘surface’ and ‘depth’, is therefore a readymade metaphor for these experiences. The transgressive act of breaking its surface-tension with a splash, like a rebellious kid ignoring the rules, running and bomb-ing into a pool, can “stand in for the unsettled “surface” of erotic desire”, Townsend tells me.

David Hockney, Spungbrett Mit Schatten (Paper Pool 14), (1978)

In America, Hockney’s swimming pools kept this erotic power, but were no longer tied up in the oppressive social proprieties of post-war Britain. The permissive atmosphere of ’60s California allowed him to explore sexuality and friendship, the whole weird soup of human relationships, through depictions of fluid surfaces.

That even working-class people had access to swimming pools as private zones of sexual exploration meant that the symbol worked universally. What’s so cool and intriguing about Hockney’s sexually charged pool-atmospheres is that he’s sharing all of our private realisations about ourselves. There’s an erotic kind of ‘how did you know?’ revelation going on.

“The web patterns that water casts along the walls and floors of a pool are known as optical caustics (from the Greek kaiein, “to burn”)”, Townsend explains to me. For Hockney, pool-surfaces burn in the California sun. So does desire.

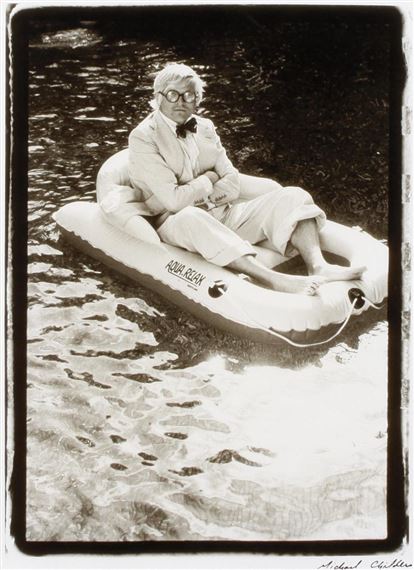

Michael Childers, David Hockney at Rising Glen, Hollywood Hills (1978)

“Water, the idea of drawing water, is always appealing to me. If it’s clear water anyway, transparent water. You can look on it, through it, into it, see it as volume, see it as surface...the idea of representing it has always rather fascinated me and I keep going back to it" - Hockney in conversation with Fran Morrison in 1980

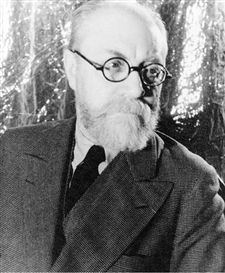

More simply, water also poses interesting formal concerns to a figurative modern painter. Hockney’s interest in water is born of his position as a classically trained, figurative artist who happened to come of age in a world obsessed with abstract expressionism. Some of Hockney’s early, art school experiments owe a lot to Jackson Pollock. His development of fluid hue is indebted to Helen Frankenthaler. But despite the trends of the time, Hockney was in love with bodies. He wanted to paint figures. Water represents a space in which light and bodies refract and bend and waver, a space in which the abstract and the object can meet.

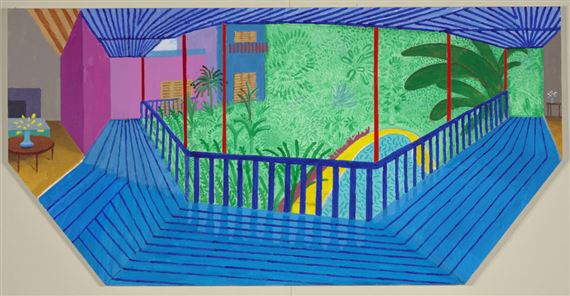

David Hockney, Interior With Blue Terrace and Garden (2017)

And so we see the surfaces of Hockney’s pools retaining the liquid-dye effect of Frankenthaler, the abstract geometries of Henri Matisse and Joan Miro, the shimmering fractals of David Bomberg. But also within and around them are classically formed, eroticized bodies drawn from a tradition stretching from Michelangelo to Lucian Freud.

The sheer variety of techniques Hockney uses in his pools, from paint applied with rollers to iPad squiggles done with a quick forefinger, means that their waters are a collision site of many different eras of art history.

Pools are expressive, explorative, ever-changing but containable. And Hockney has explored them consistently throughout his almost 60-year career. He’s on a kind of quest. And, in painting as in life, says Hockney, “If you come to dead ends you simply somersault back and carry on”. As though doing lengths in a pool.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Articles Page