Igor Vovkovinskiy was sitting on his specially made, reinforced couch in a specially made living room designed with cathedral ceilings to give him some headroom and reinforced floorboards to carry his weight.

It was June of 2016, and his size 26, 10EEEE feet (that’s a guess—we’re 180 percent out of the standard shoe system here) were wrapped in bandages following maybe his 20th surgery in the last 10 years.

His legs, too.

READ MORE ABOUT IGOR:

Our View: As a neighbor and friend, Igor's shoes will be hard to fill

Igor Vovkovinskiy, Rochester's tallest adopted son, dies at 38

The surgeons had resigned to try and reshape his lower legs—with pins and steel—to shift the weight off his feet.

ADVERTISEMENT

Every so often, Igor shifted his body weight to relieve the stress. Every so often, he let out a long breath that sounded like pain escaping.

“I’m on horse doses of pain meds and antibiotics,” he said. “So my apologies to horses.”

Just an hour earlier, Igor was standing outside the northwest Rochester neighborhood house he shared with his mom, Svetlana.

A woman and four pre-kindergarten kids—I’m guessing some small daycare group—walked up the sidewalk toward him.

“Hello!” he said. “I’m Igor!”

The kids started asking him his height, his shoe size, how he sleeps.

The woman was apologetic, but Igor smiled. Said he didn’t mind at all.

He told them “seven-foot-eight-point three three inches” and “26” and “in a very big bed.”

ADVERTISEMENT

He held out his hands and spread out his fingers so the kids could put their hands on his to compare. The mom, too.

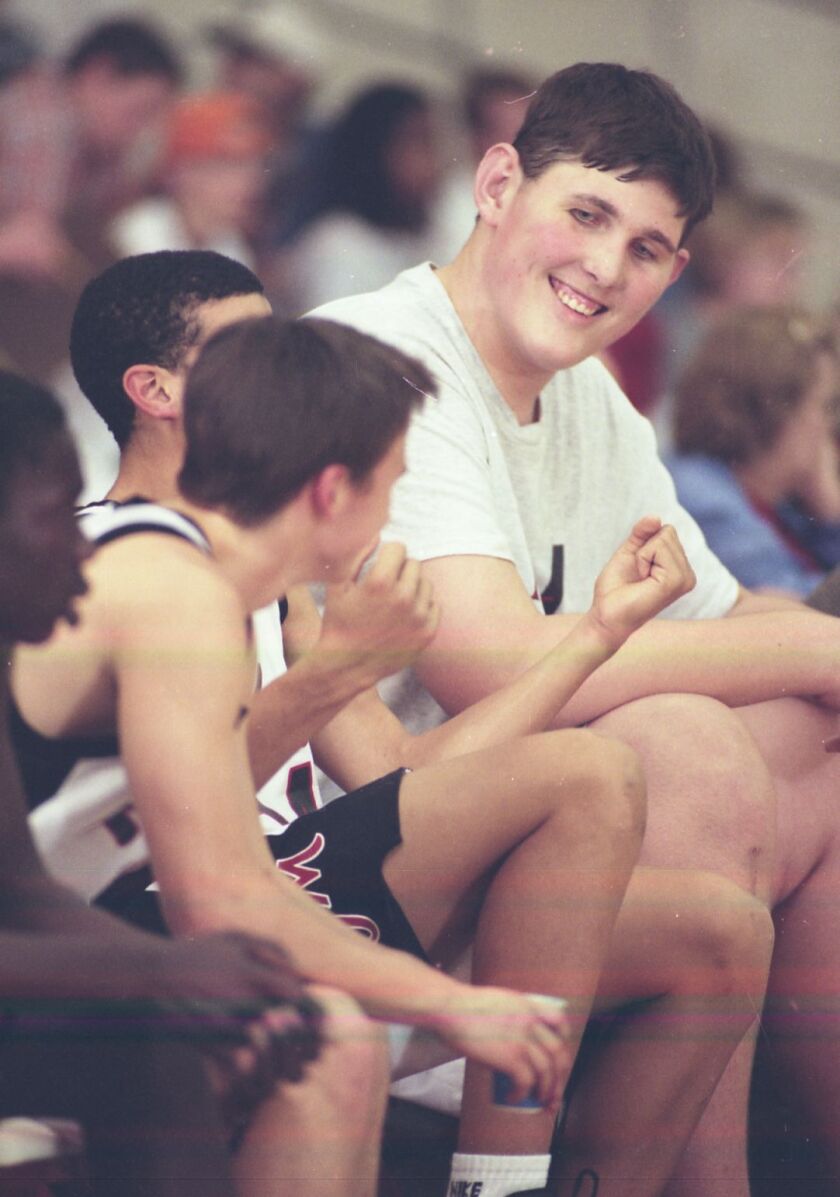

In a life where this kind of celebrity could wear on you, Igor was known as the guy who could make you feel good about yourself when you stopped him on the street, or saw him buying Diet Coke at Kwik Trip, or fishing at Lake Zumbro, or joining his older brother Oleh for a pick-up basketball game at the Rec Center.

He smiled for photos. Answered all the questions. Instinctively held out his hand for comparisons.

It wasn’t always the case. As a teen—tired of all the same questions—he said he went through a phase where he hated all the attention.

“I made up little index cards,” he said. “And they said I’d tell you my shoe size, but only for a dollar.”

He was, after all, still a kid then.

“I finally learned to embrace it,” he said. “I finally realized it was better to give people what they want, for all of us.”

So he started wearing T-shirts that said things like “Life is short, I’m not.” Started answering the “Do you play basketball?” question with “Do you play miniature golf?” Started laughing at the inevitable “How’s the weather up there?”

ADVERTISEMENT

When Igor, just 38, died in late August of this year—when his heart finally gave out—social media was dominated by feel-good stories of those who had met him for one of those chance encounters-turned-photo ops.

“My five-year-old daughter got to meet Igor, and she talked about it for a month straight.”

“My son got scared of him but he was so nice that by the end they were both laughing.”

“He made my daughter feel like she’d just met a superhero.”

But Igor Vovkovinskiy faced his share of struggles.

And he wanted you to learn from it.

“Igor was born big”

Igor Oleksandrovych Vovkovinskiy was born on September 18, 1982, in Bar, Ukraine, a city of 15,000 people with a history dating back to the 13th century.

ADVERTISEMENT

His parents—Oleksandr Ladan and Svetlana Vovkovinska—also had a 6-year-old son, Oleh.

“Igor was born big, nearly 11 pounds,” Svetlana told “60 Minutes Australia” in 2012. “Everyone was happy. In the old countries, the bigger the baby is, the happier the parents.”

Soon, though, Svetlana realized that Igor was off the growth charts. Standard deviations did not apply.

“By the age of a 1-year-old he was the size of a 3-year old,” she said. “I was pretty concerned.”

On his first birthday, Igor weighed 50 pounds. He was 3 feet tall.

Soon after, the family moved to Kiev, Ukraine’s capital and largest city (nearly 3 million people), the industrial-meets-cultural center described as “the mother of Slavic cities.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Svetlana took Igor to doctors in Kiev, then Moscow. The doctors could diagnose the tumor pressing on his pituitary gland. They didn’t want to risk surgery.

Svetlana enrolled Igor in a Russian-speaking grade school. Her son continued to grow at an alarming rate. By the age of 6, Igor was 6-feet tall. He weighed 200 pounds.

When Igor remembers his days in Kiev, he recalls the weekends spent at a beach on the Black Sea. He remembers the food, especially plates of vareniki—Ukrainian dumplings. But he also remembers realizing he was different. He recognized the stares at an early age.

The stress of it all took a toll on Oleksandr and Svetlana. They divorced after 17 years of marriage.

Svetlana, a cartographer, raised her two sons. Continued to reach out for help for Igor. She wrote to the Red Cross in Switzerland. Sent letters to doctors and hospitals around the world.

Then she contacted Mayo Clinic. And then she found Dr. Donald Zimmerman, a pediatric endocrinologist she would call “the miracle doctor.”

Mayo Clinic agreed to absorb the costs of Igor’s care. A pharmaceutical house agreed to donate medicine.

“That small gland influences nearly every part of your body.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1989, Svetlana and 7-year-old Igor flew to Rochester and spent three weeks at the Northland House (now the Ronald McDonald House).

Mayo doctors diagnosed Igor—a kid still carrying a Ziggy doll and wearing a Mickey Mouse shirt—as a possible “pituitary giant.”

Igor had a tumor the size of a tennis ball at the base of his brain. That tumor was pushing on his pituitary gland. The pituitary gland, according to Mayo Clinic, is the “small, bean-shaped gland situated at the base of your brain, somewhat behind your nose and between your ears.”

“That small gland influences nearly every part of your body.”

For Igor, that tumor caused his pituitary gland to release growth hormones. Too many hormones. And too often.

Igor was already outpacing the growth rate of Robert Wadlow, the world’s tallest verified person at 8-foot-11 inches. Wadlow, the “Giant of Illinois” died in 1940. He was 22 years old.

Without treatment, doctors told Svetlana, Igor was on pace to be 9-feet tall.

Doctors prescribed two drugs—bromocriptine and somatostatin—to shrink the benign tumor. Then came the operations.

In January of 1990, Mayo surgeons made an incision in the upper gum above Igor’s teeth, and used a tool—“like a wire loop on a stick”—to snake through his sinus to the pituitary gland. They removed as much of the tumor as they could.

They knew, they said at the time, that his heart would probably be weakened by the procedure. They didn’t have any other options.

And Igor, they realized, would need more surgeries. More drugs. While the treatment helped slow Igor’s growth, it didn’t stop it. Doctors determined Igor would need care until the end of his growth period—his late teen years.

The planned month-long visit stretched on into three months, six months, a year.

“I worry if we have to go back to Kiev,” Svetlana told the Post Bulletin in 1990. “It is so bad there right now. It is uncertain if we could find even simple medicine for him there. Without it, he would die. I’ve been with Igor my entire life, I can’t imagine life without him; I am his mother.’’

Svetlana enrolled Igor in the Rochester School District. Re-applied for their visas every six months. When immigration officials threatened to send the family back to Ukraine, Mayo Clinic hired lawyers—and reached out to local lawmakers. The family was allowed to stay.

Svetlana took jobs cleaning houses. Took classes at RCTC to become a registered nurse. Got her degree and a job at Mayo.

And so it went.

When he started fifth grade at Lincoln at Mann, 10-year-old Igor was 6-foot-6, 300 pounds, and sporting size 18 Reeboks.

As a 12-year-old, Igor joined the Rochester Youth Baseball Association. When he couldn’t bat because there were no helmets to fit his head, his coach and the RYBA worked with a Cannon Falls company, Gemini, to custom make a helmet.

Sure, he struck out in his first at bat. But then managed three straight hits. When he scored his first run, his teammates and coaches were waiting at home plate to give him high-fives.

As a 16-year-old at John Marshall, the then-7-foot-5 Igor played in his first JV basketball game and finished with four points, two blocked shots, and three rebounds. He played a bit on varsity, but suffered a stress fracture in his foot. Fractured an elbow during a fall.

So Igor read Ukrainian history. Took computers apart and rebuilt them. Played Nintendo and Gameboy.

When he got his driver’s license, his mom bought a Plymouth Voyager and retrofitted the van’s driver’s seat so it was lower and could be adjusted all the way back until it hit the seat behind.

Igor, meanwhile, started to find his voice.

There are the stories of Igor standing up for classmates, especially those being singled out.

Like the freshmen kid getting picked on in the lunchroom, until Igor walked by and said, “Leave him alone.”

Or the high school junior, who barely even knew Igor, but was pregnant—“visibly pregnant,” she tells us—and facing her own problems. She tells the story of when Igor passed her in the hall and he said, “Let me know if anyone gives you a hard time.”

He could relate.

As a high schooler, he wrote letters to the editors of local newspapers.

“Community needs teen center” and “We all deserve the basics.”

He graduated from John Marshall in 2000, earned an applied science degree in IT from Rochester Technical and Community College in 2003. Took classes in paralegal studies at the Minnesota School of Business.

Worked weekends as a clerk at Sam’s Club. Took a job at Mayo Clinic answering phones for the internal technology helpline.

Then came more surgeries. Maybe 16 surgeries, he guessed, between 2006 and 2012.

“Sometimes,” he said, “I have pain that is so severe I have a picture in my brain of a truck that keeps running over my leg. Sometimes for three or four hours at a time. It’s hard to breathe. I see black spots. My heart starts hurting.”

His mom, meanwhile, became an ICU nurse working at Mary Brigh.

In 2009—wearing his now-famous “World’s Biggest Obama Supporter” T-shirt—he stood out among the 15,000 attendees for a rally for President Obama at the Target Center in Minneapolis.

“The biggest Obama fan in the country is in the house—I love this guy,” Obama told the crowd as he pointed out Igor. They met after the rally, got photos taken together.

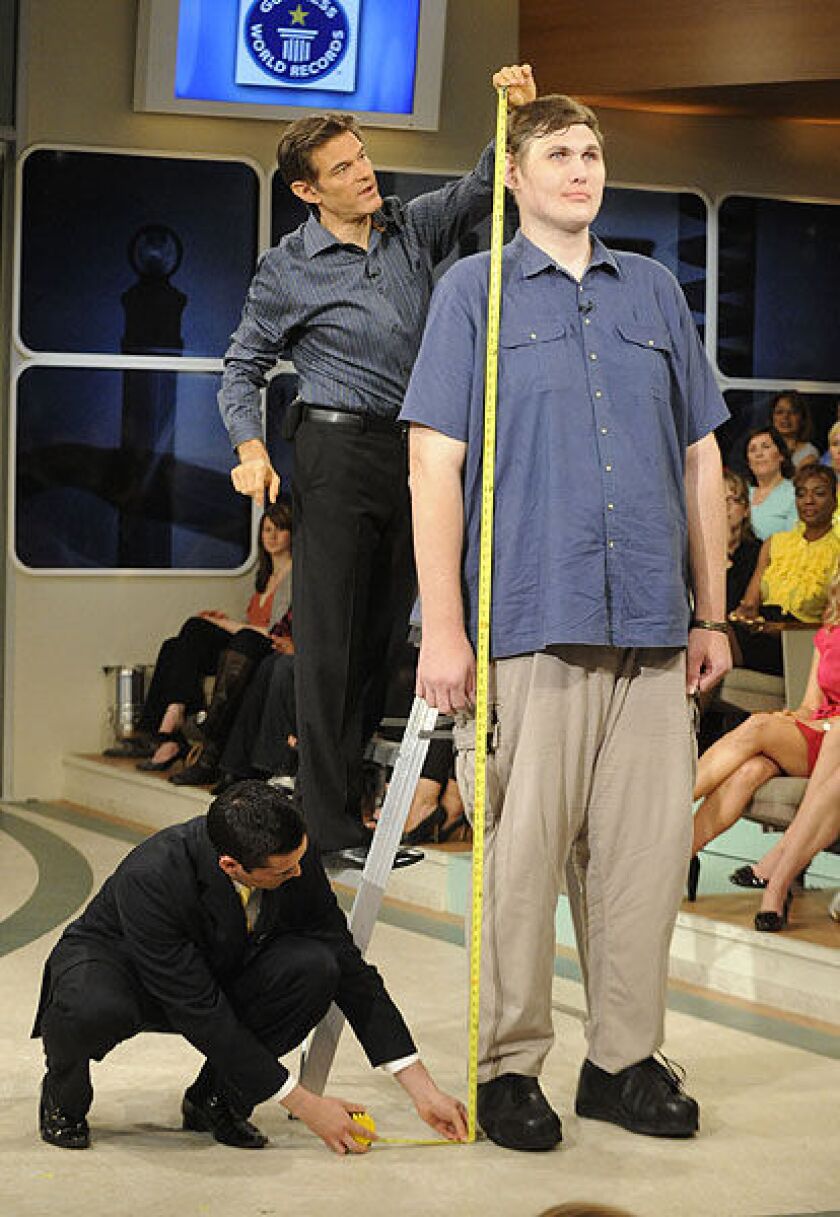

In 2010, in an appearance on the “Dr. Oz” show, Igor Vovkovinskiy, after an official measurement taken by an adjudicator from Guinness World Records, was certified at 7-foot-8.33 inches, “The Tallest Living Man in America.”

He had, by then, fulfilled that Mayo prediction and had become a true pituitary giant—one of the maybe 100 or so documented cases in medical history.

Cases like Anton de Franckenpoint (known as “Long Anton”), a military guard during the Thirty Years War, who—-in the 1590s—was the first verified person to reach 8 feet tall.

And 7-foot-4-inch, 520-pound professional wrestler Andre the Giant.

And George Bell, the 7-foot-8-inch Virginia sheriff (and former Harlem Globetrotter), whom Igor took the title of America’s Tallest Living Person from when that 2010 measurement revealed that extra third of an inch.

The title brought even more attention.

In 2011, he got a small role in the movie Hall Pass.

“Someone from the movie saw the documentary about me on TLC (‘Help! I’m Turning Into A Giant’),” he told me. “They asked me to come behind the scenes to see how everything is made. While I was there, one of the Farrelly brothers, who were directors, sprang on me that the writers had added me to a scene. My jaw dropped to the floor. Hell yeah, sign me up! I had so much fun. I met Owen Wilson, Jason Sudekis, Jenna Fischer, Christina Applegate, the Farrelly brothers.”

In 2013, he was the talk of the Eurovision song contest in Malmo, Sweden, when (dressed as a fairy tale king) he carried Ukrainian singer Zlata Ognevich (dressed like a fairy) on stage.

By 2014, when the Russo-Ukrainian War was in full swing, Igor became a staunch and vocal supporter of Ukrainian troops.

He raised money—by selling autographed photos, by selling some of the shoes he’d outgrown—for the troops.

“Ukrainian freedom fighters should be celebrated and supported by everyone,” he said. “They are standing up to the bullies of the world.”

“My real hero is my mom”

During that interview in his home in 2016, mom Svetlana was in the kitchen, making Igor’s favorite meal, borscht, a beet soup popular in Eastern Europe.

She was—and it felt like this was probably always the case—looking out for him. Gently steering him away from certain topics.

When I asked him about his heroes, he listed “The young and old men who are fighting against Putin’s aggression in east Ukraine.”

And “Nadiya Savchenko, a woman who fought with her words and actions against the corrupt and Putin controlled justice system.”

And “Every man, woman, and child who stood against government oppression, everyone who stood in lines interlocking arms with each other in Ukraine.”

When Svetlana was out of earshot, though, he said, “My real hero is my mom. She has done so much for me my whole life. It’s tough, sometimes, having to live with your mom when you’re my age. I’ve learned to care for people more because of what I’ve been through and because of her. She cares so much for people.”

He started talking about her work as an ICU nurse.

“She loves working with people who need help the most,” he was saying. “They love her. She always fights for them and they tell her she’s the best nurse they’ve ever had. She’ll bother the doctor as much as she has to for the patient to be comfortable, to get what they need. She never gives up caring no matter what.”

Though it still felt like he was talking about something more.

He told me about the book he was currently reading (The Favored Daughter: One Woman’s Fight to Lead Afghanistan into the Future), and how his heart will always be in Ukraine (“I don’t think it’s something that will ever go away. ... It’s a different culture. A different way that people treat each other. Something about it, we deeply miss.”).

As I was leaving he said, “You never mentioned my height.”

I didn’t realize it, either.

I said something like, “I’m sure you’ve been asked that enough.”

I told him, then, that I had always appreciated how, when I’d gotten to talk to him, it always felt like he was telling his story for some other reason. How it always felt like he was telling it with the hope it might just help someone else.

With a big picture view. With a take on the world that few people could understand.

I said goodbye, then, and walked through that 9-foot doorway.

Igor, though, followed me outside. It was painful to watch him move.

“People take everything for granted,” he said, as we stood in his driveway. “Even simple things. I can’t go anywhere with my friends in their car. I can hardly go to anyone’s house because I’m afraid I’ll break their furniture. Their ceilings are low. Their doorways are low. The pain I have is pretty much 24 hours a day.”

He shifted his weight from one foot to another.

“Sometimes the pain is so bad I can’t do anything useful. I try to think about something else. Read a book. Skype with my friends from Ukraine.”

You could tell it was a message he wanted people to hear. For their sake.

“So, I think that even for the simple things in life, people should be more grateful. Especially because you live in America. Really count your blessings. Really appreciate all of the little things you have.”

And with that he slowly made his way back into the house. Back to his mom and his favorite meal.

“Plyve Kacha”

Igor Oleksandrovych Vovkovinskiy died on Friday night, August 20, 2021 at St. Marys Hospital, with his mom and brother at his side.

“His last dinner was a piece of Kiev cake and Fanta,” wrote Svetlana on Facebook. “A few hours before his death, he was accompanied by Oleh’s wife Alla and children. Igor was glad to see them, and although it was difficult for him to speak, he tried to joke about his nephew Andriy, whether he had learned the Ukrainian language in a month in Ukraine.”

At his funeral, a week later, they played “Silent Night” and “Plyve Kacha,” a Ukrainian folk song-turned-anthem to the freedom fighters of Ukraine.

The pastor talked about Igor’s love for his family. About his love for Ukraine. About how he wanted other people to learn from what he had experienced.

Afterward, standing around in the lobby, everyone was telling stories of his smile and his laugh and his thoughtful insights on life.

No one mentioned his height.