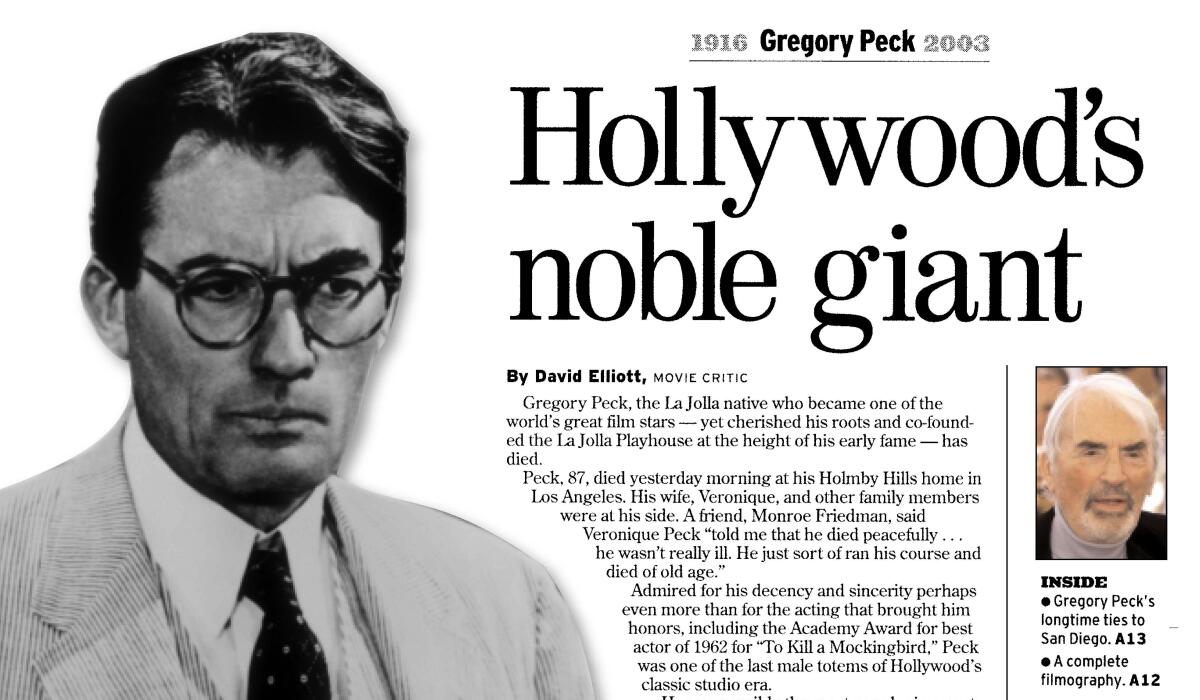

From the Archives: Gregory Peck

Gregory Peck, a La Jolla native who co-founded the La Jolla Playhouse and became one of the world’s great film stars, died 20 years ago this week. His death on June 12, 2003, at the age of 87 came days after the groundbreaking for a $16.5 million facility at the playhouse he loved and served so well.

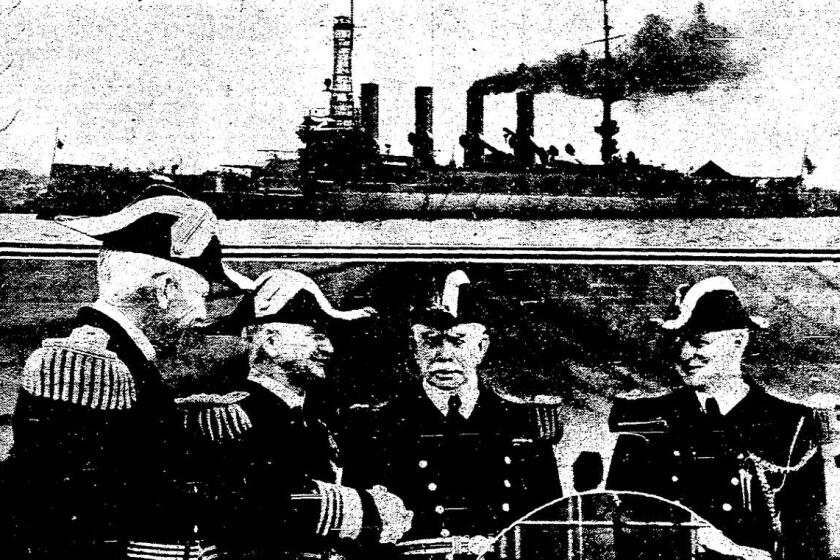

Forty-five years ago, Gregory Peck, starring as a General Douglas MacArthur, spoke to the Union’s James Meade in between filming scenes from Universal Studio’s “MacArthur” around San Diego.

From The San Diego Union-Tribune, Friday, June 13, 2003:

Hollywood’s noble giant

By David Elliott, Movie Critic

Gregory Peck, the La Jolla native who became one of the world’s great film stars — yet cherished his roots and co-founded the La Jolla Playhouse at the height of his early fame — has died.

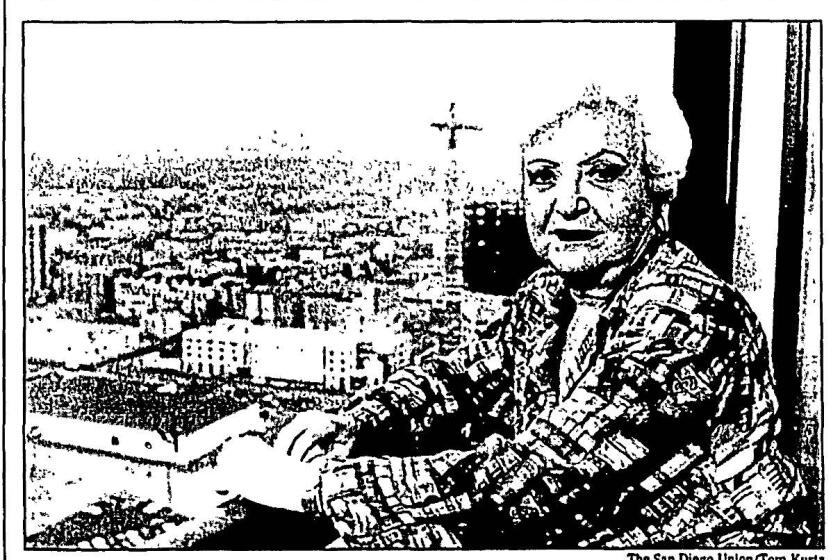

Peck, 87, died yesterday morning at his Holmby Hills home in Los Angeles. His wife, Veronique, and other family members were at his side. A friend, Monroe Friedman, said Veronique Peck “told me that he died peacefully . . . he wasn’t really ill. He just sort of ran his course and died of old age.”

Admired for his decency and sincerity perhaps even more than for the acting that brought him honors, including the Academy Award for best actor of 1962 for “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Peck was one of the last male totems of Hollywood’s classic studio era.

He was possibly the most popular in a postwar bumper crop that included Robert Mitchum, Marlon Brando, Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster.

He also received best-actor Oscar nominations for “Keys of the Kingdom” (1945), “The Yearling” (1946), “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1947) and “Twelve O’Clock High” (1949).

“He was someone who achieved international success yet never lost track of his roots,” Des McAnuff, the La Jolla Playhouse’s artistic director, said yesterday. “He saw opportunity here. He’s had a huge impact on the performing arts in San Diego, and we at the playhouse owe him our existence. He came home, when he didn’t have to, to create an institution that will last.”

Blessed with a rich, resonant speaking voice and looks that endured age well — although he knew how to step away from films once his romantic leading days were done — Peck defined a form of earnestly intelligent, honorable, American manliness, most famously in “To Kill a Mockingbird” and most charmingly as a mischievous reporter in 1953’s “Roman Holiday.”

That classic, which made Audrey Hepburn a star, might not have been filmed but for Peck’s agreement to star. True to his form, it became a gentleman’s agreement. He said he refused to take solo above-the-title billing because “once I saw that girl, I knew this was not going to be a Gregory Peck picture.”

He was the one star to whom the term “Lincolnesque” was regularly applied, and was praised by a friend for having Abraham Lincoln’s “reticent majesty,” although he only played the 16th president (his favorite hero) for one TV film. A staunch Democrat and supporter of liberal causes who was proud to have made President Nixon’s enemies list, Peck was often mentioned as a possible candidate, a temptation turned aside by his innate privacy and modesty.

Peck, born on April 5, 1916, was the only child of La Jolla pharmacist Gregory “Doc” Peck and his wife, Bernice.

Money was tight; when an employee stole $10,000 from the drugstore, Peck’s father was too embarrassed to go to the bank for a rescue loan and lost the business.

Peck later recalled the San Diego coastal community as “a quiet little fishing town, and the only thing rich about me was my first name -- Eldred.”

Eldred became a child of divorce, living with either parent in various cities, for a time enrolled in a Los Angeles military school run by nuns for children from broken homes. “I was full of self-doubt,” he said.

By the age of 17, he was 6 feet 2 inches tall and on his way to the rugged handsomeness that captivated many women who saw his early films -- a fair reward, for he credited girls with having broken down his shyness.

But first, after dropping out of San Diego State College, he spent time as a trucker and at UC Berkeley, where he studied pre-med to please his father.

The strapping student was recruited to play Starbuck in “Moby Dick” for the Little Theater, and the acting bug bit him. If never the most expressive of actors, he became a marvel of taste and subtle inflection.

After graduation, Peck studied at Sanford Meisner’s famous Neighborhood Playhouse School in New York City after being auditioned there by the great Martha Graham. He was poor, and spent some nights sleeping in Central Park. “It didn’t seem a hardship, because New York was such an adventure,” he said.

Soon he had a few Broadway credits, and in 1943 was signed to act as the young Russian hero of “Days of Glory.”

Peck, at 27, was already his own man. He refused to become a contract player, offending such Hollywood titans as MGM chief Louis B. Mayer. He opted for the freer, more supple support of producer David O. Selznick.

He won a following by playing a lovable priest in 1944’s “The Keys of the Kingdom,” and his stardom was buffed to a high shine a year later by Selznick’s and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Spellbound,” in which his character was saved from instability by a psychiatrist played by Ingrid Bergman.

As Penny Baxter, rustic father of a boy in love with a pet deer in “The Yearling,” Peck shaped an early tryout of the generous, paternal dignity he perfected 16 years later as Atticus Finch in “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Intellectual cast

His rectitude had a slightly more intellectual cast in “Gentleman’s Agreement,” a 1947 film that fought against anti-Semitism and had Peck’s character pose as a Jew while eschewing all the usual cliches of Jewishness in film. (Some called it miscasting, and Peck himself once said of his early work, “All I had was sincerity.”)

There followed a fast run of movies, not all hits but all A-list works that by the 1950s made Peck a paragon of class on screen, about as popular with men as with women. In the very non-Peck film “La Dolce Vita” in 1961, a jaunty prostitute saluted the allure of Marcello Mastroianni by calling him Gregory Peck.

If not so successfully as Lancaster and Douglas, Peck sought to vary his image beyond iconic integrity. Some disparagers called him “wooden,” but his fans loved the actor for what seemed not just goodness but the charismatic conviction of goodness.

Among the early vintage Pecks was the extravagant western “Duel in the Sun” (1946, with one of his few, sexually forward rascals) and the more subtly stylized western “Yellow Sky” (1948); the popular naval saga “Captain Horatio Hornblower” (1951); the wry British comedy “Man With a Million” (1954); the brooding war drama “The Purple Plain” (1954); and the very current drama about middle-class boredom and guilt, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” (1956), in which Peckian nobility was involvingly blemished.

With veteran director Henry King, Peck enjoyed a long run of strong works: “Twelve O’Clock High” (1949), as bomber leader Gen. Frank Savage, one of the most moving military portraits; “The Gunfighter,” a 1950 western full of terse melancholy; “David and Bathsheba” (1951), a restrained Bible story in which he eloquently recited the 23rd Psalm; the Hemingway tale “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” (1952) in which he had one of filmdom’s longest death scenes; and a western revenge drama, “The Bravados” (1958).

Lasting friends

His own favorite of his young prime was William Wyler’s “Roman Holiday,” a gracious triumph of fairy-tale tourism in which Peck partnered Hepburn with infallible, often amusing ease. Rumors of an affair flitted around, but they were fast and lasting friends.

Instead, during that production, Peck fell in love with French interviewer Veronique Passani; marriage made them one of Hollywood’s premier couples. She later said, “The more I know him, the happier I am,” and he said, “I didn’t know who I was until I met her.”

They shared a 4-acre, hillside home of traditional elegance, a place full of children and dogs and paintings. Peck said, “I don’t think I’ve ever been thrown off my center by Hollywood fame or publicity.”

He was divorced by first wife Greta Rice Peck in 1954, and remained close to their sons Stephen, Carey and Jonathan. (Jonathan committed suicide in 1976. Said Peck: “You never get over a thing like that.”) With Veronique, Peck had a son, Anthony, and a daughter, Cecilia.

Peck’s contribution to theater was his co-founding of the La Jolla Playhouse in 1947 with Hollywood friends Mel Ferrer and Dorothy McGuire. It was sort of a lark that turned serious, a chance for movie actors to “hit the boards” and practice craft away from the studios.

But Peck gave it more than his acting presence, and with Ferrer was the main motor of its early years. After a darkened period, the playhouse rebounded under other leadership to become a top American theater, for which its most famous founder was happy to raise money and give time.

In films, Peck took a big gamble as tortured Captain Ahab in John Huston’s “Moby Dick” (1956). In the majority opinion it did not quite pay (“Abe Lincoln eats whale blubber,” sniped one critic), but neither was it an embarrassment. At one point, tied to the artificial whale, he was lost for some time at sea among 10-foot-high waves.

Peck bounded on, making his own deals, sometimes producing, starring in such landmarks as Wyler’s enjoyably lavish western “The Big Country” (1958); the drama of nuclear despair “On the Beach” (1959), the fact-based Korean War film “Pork Chop Hill” (1959), the hugely popular war escapade “The Guns of Navarone” (1961) and the classic thriller “Cape Fear” (1962), in which he was out-acted by hulking menace Robert Mitchum.

Nobody stole his quiet thunder in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” in which he put “everything I had” as an actor, and which finally brought him the Oscar.

Tender but not drippy, eloquent but not preachy, noble but not ponderous, his liberal lawyer Atticus Finch -- named the top movie hero in a recent American Film Institute poll -- became the ideal champion of afflicted Southern blacks and the ideal father of all yearning children.

The role had the glow of marble well before it was gilded by the motion picture Academy, but Peck gave much credit to his La Jolla roots, and said, “My father was quite a bit like Atticus.”

Spirits remained high

His career after the Oscar paid financial dividends but was in decline creatively, although his spirits remained high. (“When I’m driving to the studio, I sing in my car,” he said.) Among his few disappointments was not starring in a new filming of “Dodsworth.”

There was the blithe fun of the suspense stories “Mirage” (1965) and “Arabesque” (1966), then the artful western “The Stalking Moon” (1968). But there were too many budget packages like “How the West Was Won” (1962), “Behold a Pale Horse” (1964), “Mackenna’s Gold” (1969) and the heroic yet turgid “MacArthur” (1977).

Not only critics hooted when he played the Nazi Dr. Josef Mengele in “The Boys From Brazil” (1978), in which Peck and Laurence Olivier seemed like hocks of ham set upon by ravenous dogs.

His top grosser was “The Omen” (1976), a horror mystery in which he played the adoptive father of Satan’s offspring. Labors of love if not major glory included “Trial of the Catonsville Nine” (1972), “The Dove” (1974), some TV films and his last imposing work, “Old Gringo.” In that 1989 flop his Ambrose Bierce was a glowing sunset monument next to the following generation (Jane Fonda) and the one after hers (Jimmy Smits).

Seemingly shy, but briskly forceful in opinion and action, Peck had a saltier aspect than his public image allowed. He relished the snap and surge of strong views, as when he disparaged current Hollywood bosses as “vest-pocket executives” notably inferior to the “dragons” he had served without servility.

He enjoyed film-town gossip and could tell slightly spiced jokes, then head off to make eloquent Bible recordings.

His honors along with the Oscar include a Life Achievement Award from the American Film Institute (which he helped found), the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award and the Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded by President Johnson. His contributions to charity and favored causes, such as the National Endowment for the Arts, were many.

Endowed with a goodness he came to personify on film, Gregory Peck was burnished by the good will of countless fans — his finest memorial.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.