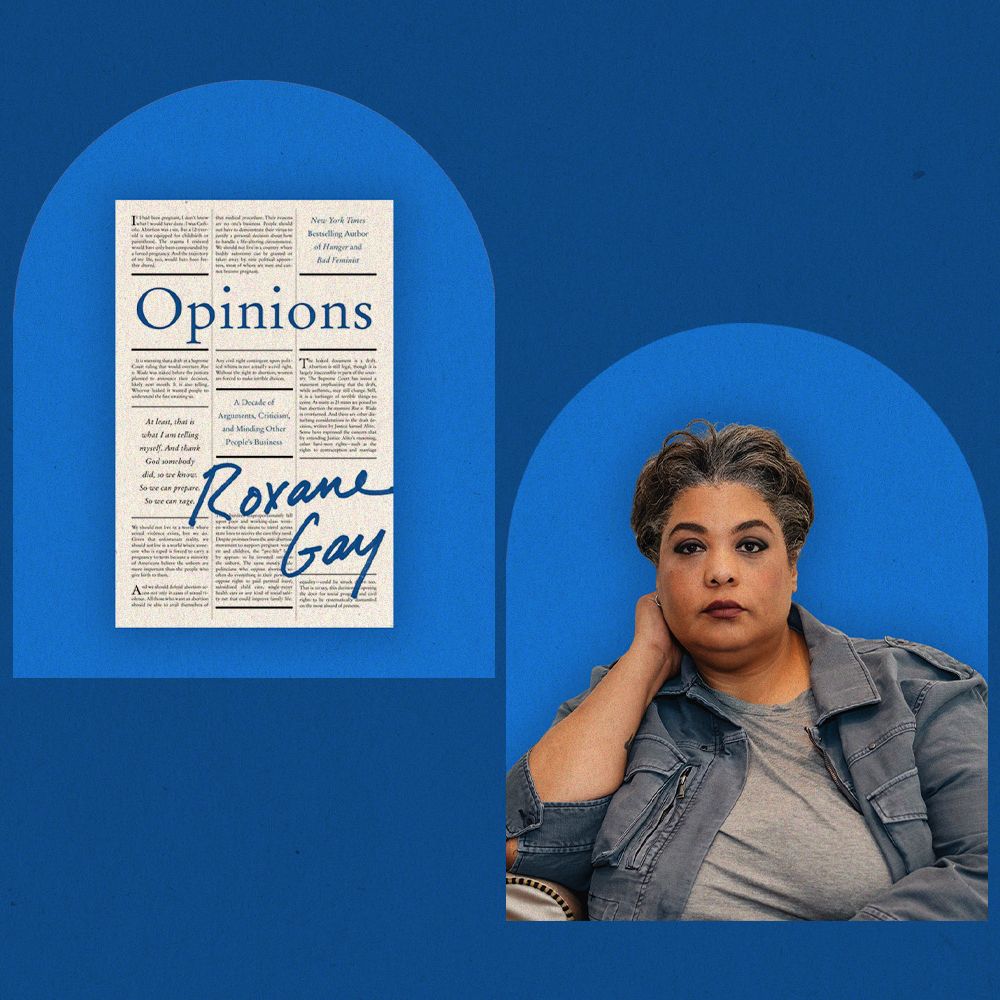

If any writer at this moment in time needs no introduction, it’s likely Roxane Gay. The author of the runaway best-selling essay collection Bad Feminist, as well as the memoir Hunger and the novel An Untamed State, amongst other titles, has made a name for herself across the internet in places like Salon and The Rumpus. She’s also cemented herself as a New York Times contributing opinion writer and oversees her own imprint, Grove Atlantic’s Roxane Gay Books. Gay is, to put it simply, a true star in the literary world known for her uncompromising opinions, timely takes on modern American culture, and in-depth profiles.

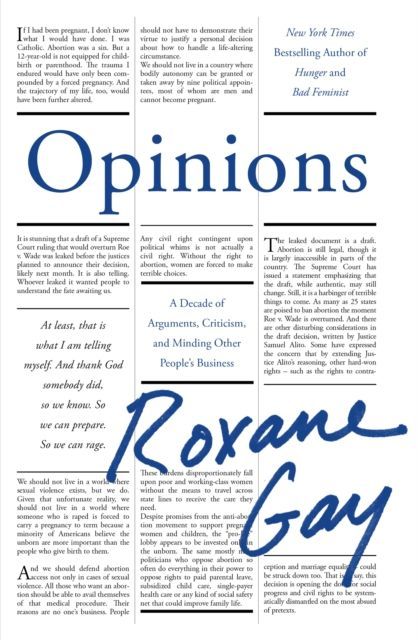

Her latest book, Opinions: A Decade of Arguments, Criticism, and Minding Other People’s Business, collects roughly the last 10 years of Gay’s opinion writing across the internet and in print. While it doesn’t quite include everything she wrote during the past decade, it does cover a wide breadth of work that, upon reading, simply reinforces the fact that Gay is still at the top of her game and has been for many years, making her one of the most important writers working today.

Shondaland recently caught up with the author to discuss the essays in her new collection, the pieces she couldn’t include, her parents’ influence on her work, why she would love to profile Beyoncé, the sweet relief of a crossword puzzle, and much more.

SCOTT NEUMYER: I find that introductions to essay collections or anthologies of collected works are often passable but not all that consequential. Your introduction here, however, is not only incredibly warranted, but it’s also really well written and helpful in understanding the book that lies ahead. How do you approach writing an introduction for a collection of pieces that you’ve published sometimes even a decade ago?

ROXANE GAY: That’s a good question. You know, you’re right. Most introductions to anthologies or essay collections are really the bare minimum because the people who write them are either sort of big names who have been invited to write them, and they don’t have enough time to do it well, or you’re revisiting old work, and you don’t know what to say about it. I just wanted to talk about what it means to argue online but also in other places. I mean, the New York Times pieces, most of them appeared in print as well. But I wanted to talk about how it has changed over the past decade, what kinds of things I’m thinking when I want to write something, what the demands are on early-career writers where you have to sort of churn to make something resembling a living. I wanted to cover all of that ground and just talk about what was going on behind the scenes, in some ways, while I was writing these essays, and how my career has evolved to this point because this is not what I thought was going to be my next book. I thought it was going to be a book that I’m still finishing — a book of writing advice. And so, when I decided to put this collection together, as I was going through all the pieces, I just was trying to be as reflective as possible. And really look at “What did I do here?”

SN: The pieces in the book itself, clearly they all fall under the category of opinion pieces, but you don’t include everything you’ve written over the last 10 years. It would be impossible. So, how do you decide which stories make the cut and ultimately how to organize them?

RG: The organization, I think, is loose. I think many of the pieces could be in many of the categories. So, I was just “going on vibes,” as the kids would say, really thinking about what is the main thrust of the piece and would it fit in this broad category. And so, I kind of took it that way. And then, within each category, for the most part, the pieces are chronological so that you can, hopefully, see an evolution, and at the same time, in terms of some of the pieces where we’re looking at politics or race and police violence, you can see that nothing is changing, that you’re being forced to essentially write something very similar over and over and over again because the same terrible things keep happening over and over and over again. So, I tried to pick the pieces that would fit within these categories in the sections that I created. And it’s not everything I’ve written over the past 10 years, but it’s a fair amount. It’s the stuff that I feel like is the most consequential or also the most fun, like the Father’s Day piece or why I hate the beach. You know, most of it when you write about social justice, gender, politics, race, sexuality, it’s not the most fun beat in the world, and that’s okay, but I did also want to include a few pieces that were a little lighter because not everything is terrible.

SN: And then, on those pieces where you’re talking about race and police violence, is it traumatizing to not only have to write that story again and again and again and again, but to also be the one whom the editor immediately calls? They immediately think you’re the go-to person to write that. That’s gotta be traumatizing.

RG: It can be, but I have really firm boundaries over what I will and won’t do in order for it to not be traumatizing. I’m at a place in my career where I don’t have to do it. I only write what I want to write at this stage. And if I don’t feel like I have something to say, I won’t write about it. And I’ve also made it a point that I don’t write about every instance of police violence, not because it doesn’t matter, but because I may not necessarily have something useful to say on that topic. I’m also in a place where I can tell editors, “God forbid I’m the only person in your Rolodex. I shouldn’t be at this point.” But I’m happy to give them other names of people who might be available, or might be interested, or might be more appropriate. And so, that really helps to mitigate the trauma of witnessing trauma. It’s challenging, but I try very hard to not let it get to me.

SN: Were there any pieces that you really would have loved to include in this book, but they just didn’t seem like a good fit, or for any other reason, you couldn’t get them in?

RG: There were some longer pieces that I’ve written that I would have loved to get in, but all of the pieces in this book, except for the profiles, are in the 1,200-to-1,600-word range, if not shorter. I’ve written some 5,000-, 6,000-, 7,000-word essays, and I’m just going to save those for a book where something of that length would be more appropriate. I think that if you’re reading a bunch of these shorter pieces, and then, boom, here’s a 10,000-word essay, it just wouldn’t work. And so, even though I am very fond of those pieces, and I would like to put them into the world, I recognize that this wasn’t the right medium for that.

SN: You also say in the introduction that sometimes you dread publishing a specific essay. You write, “Sometimes I write something and choose not to publish it simply because I don’t want to deal with the bulls--t.” Are there any pieces that you’ve held back throughout the years that you still go back to and have the desire to publish? Do you ever think you’ll find an outlet for those pieces?

RG: Probably not, because they were so pinned to the news cycle, and most of them were in 2016, around the election. I had about two or three pieces I wrote about Hillary Clinton [in support of Clinton]. So, I wish I had published those, but it would be really weird to publish it today. That’s the challenge when you do opinion writing. It’s very timely, and I try to approach it in a way that will also be timeless, but there are some things that I just wouldn’t be able to find a home for now.

SN: The internet has evolved (and honestly, devolved) since you started writing and publishing essays. As someone who came up in the age of the internet and found success in places like Salon and The Rumpus, how do you think the internet today differs from the internet when you first started publishing? Do you see hope in outlets like Substack that might allow for lengthier writing in closer communities?

RG: I don’t know that I see hope. I see opportunity. I think it’s great that Substack and other similar communities exist, but they’re filling a void. And I think it’s a real problem that that void is gone, and that puts the onus on the individual. If you are a writer without an audience and without connections, Substack is great as a tool, but it’s really hard to build an audience. Most of the people who are finding success on Substack came with audiences. And some of these people have enormous audiences. There used to be so many more outlets. Of course, they didn’t pay all that well, if they paid at all, but they were there, and we have seen this contraction that is getting worse and worse. And at the same time, the web is unreadable. Right now, all of the pop-ups about privacy, which I appreciate, but you know … and all of the ads, it’s simply like we have made something that is entirely nonfunctional, and that’s a real shame. I don’t like video. I never click on a video unless it involves Beyoncé [laughs]. I would rather read my news. It’s just how I prefer to process things. So, seeing the shift to video and then recognizing it didn’t work, it’s just a shame. I do hope there’s some kind of renaissance, and these things are often cyclical, so I know that it’s not the end of the world. We are not the generation to end print or prose, but it’s still disheartening to see how much things have changed in a decade.

SN: You mention both of your parents in your introduction, saying that your mother gave you the freedom to have and share your opinions, while your father’s first instinct seems more to want to protect you. Can you talk a little bit about the influence and effect your parents have had on your writing and your life?

RG: My parents are great. No parent is perfect, but they certainly gave my brothers and I an amazing foundation to work from. We were very loved as children. They were intense about education, but I understand now why. They give us a drive to learn and to do well at learning. So, that was amazing. And we always had these discussions around the kitchen table — we ate dinner as a family almost every night — and they talked to us like little people, not just children. They really engaged us, and they encouraged us to share our thoughts on the world. I think that was really helpful in making me feel like even if I don’t feel like I have a voice worth listening to, I know I have opinions, and perhaps I can just share them with the five people that are going to read this piece online. So, that was really helpful.

And my mom is just a lot [laughs]. She is very opinionated. My wife the other day said to me, “You come by it all honestly.” I was like “I do. None of my quirks are my fault.” It’s really awesome to just mention them. Nobody comes out of nothing. Well, a few people do. … But you know, I was definitely a product of good parenting and loving parenting, and I don’t take it for granted.

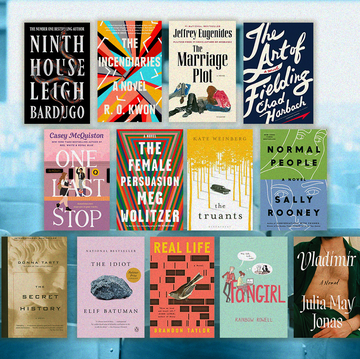

SN: The first three books from your Roxane Gay Books imprint are being published (or have been published) this year. What have you learned from publishing other people’s work that you’ve been able to put into your own work?

RG: Well, I’ve learned that publishing work is hard. I knew it was challenging certainly, but I’ve had a fairly lucky journey through book publishing. And it’s not even about sales. But my books have been edited. Even when the advance was very low, my publishers took me out on tour, things like that, and my publicists publicized my book. I’ve had the fortune of being a lead title with most of my books, and so my books have gotten the attention that every book deserves. And when you publish books, you realize why not every book gets the attention it deserves. There’s simply not enough to go around, which I think, of course, introduces the conversation about “Are we publishing too many books?” But who are we going to say no to that’s currently being published? So, I don’t know how to fix it. But I just have more understanding of how publishing works, and it has just made me more mindful to not take for granted the opportunities that I have in terms of publishing my own books. And it just makes me also appreciate the teams that work on my books because it’s just so much work. I don’t mind it, but for newer writers and debut writers, to build something out of nothing is really hard. I know most of us have done it at some point, but literary success truly is that combination of drive, talent, and of course, the most important ingredient, which is luck. And not everyone gets lucky that deserves it.

SN: You mention that celebrity profiles are not your favorite genre of writing, but you’re so dang good at them. Is there a celebrity or public figure you would love to profile whom you haven’t gotten to yet?

RG: Beyoncé. The answer is always Beyoncé. But here’s the thing with Beyoncé … I would love to have a real conversation with her and be able to formulate the questions myself. She has a lot of control over her image, and she interviews herself, and I understand where it comes from. And frankly, she is at a place in her life where she gets to do that, and I respect that. I would love to profile her, and really ask challenging questions, and get in there. And then, I want someone to pay me to write 10,000 words about it. I just find her to be very interesting. She is one of those people who has made a successful art from pop star and child star to, at least from the outside looking in, she seems fairly well adjusted and happy.

And I would love to profile Hillary Clinton and just ask her, like, “How did you handle those first few months where you just knew that the most odious man alive was going to be president, even though you were far more qualified and had won the popular vote?” And, you know, “How have you dealt with the many public ups and downs?”

There are a lot of interesting people out there, and I have been fortunate enough to profile some very interesting people. Sarah Paulson was a delight.

SN: As someone who’s incredibly busy with the imprint and doing your own work and all this other stuff, how do you take care of yourself? What do you do for self-care?

RG: Well, I’m of a generation that is skeptical of self-care, I think. I do recognize that it really is important that we care for ourselves and that it’s actually not cool to just be so laissez-faire about everything, so I try to go to therapy twice a week, but I at least go once a week, and it does help. That is useful. I also try to do things that I find enjoyable, like theater, concerts, and movies. I enjoy being entertained. I love going to museums. I like to do things, and I’m fortunate enough to live in two cities where there are many things to do. But I also have no problem taking downtime, and watching really trash television for a very long time, and doing crossword puzzles. And so, I just try, even though I’m working all the time, to say, “You know what, Roxane? You’re still not going to make that deadline, so let’s do a crossword puzzle.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from central New Jersey whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, The Boston Globe, AARP, Parade magazine, and many more publications. You can follow him @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY