Germany's Raw Pork Sandwich Isn't As Scary As You Think

I recently traveled to Berlin, Germany to visit some friends, and before I went, I made a mental list of foods I needed to try while I was there. Of course, this included German classics like pretzels, eisbein (simmered pig knuckle), and sauerkraut. I also made sure to eat as much of Berlin's amazing Turkish food as I possibly could. But there was one dish on my list that filled me with a mix of anticipation and fear: an open-faced sandwich made with raw ground pork, or "mett." The idea of eating raw pork challenged my North American ideas about food safety, but I read that the dish was ubiquitous in Berlin, and I confirmed that firsthand when I landed in the city.

I ate the raw pork sandwich, enjoyed it, and lived to tell the tale. You won't find me eating raw ground pork from my local Kroger anytime soon, but I'm glad I tried it in Germany. Please allow me to explain raw pork's place in the German diet and why it's not as scary as you might think.

What is mett?

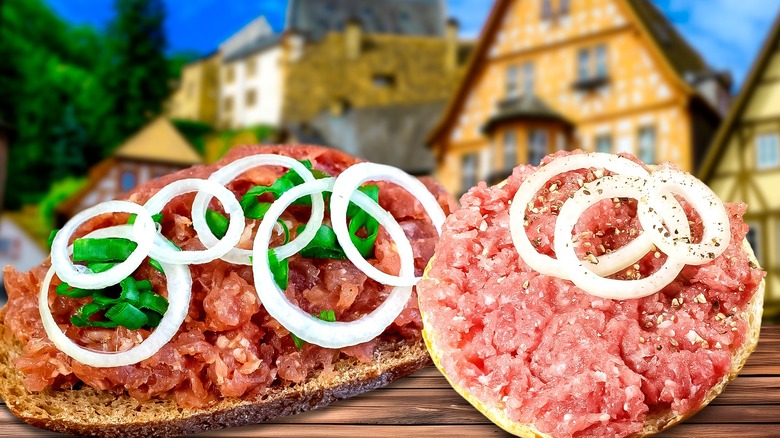

The German locals I spoke to told me that mett refers specifically to minced or ground raw pork, but the term is also used as a shorthand for the most common way this meat is consumed — as an open-faced sandwich on top of a halved white roll, usually with salt, pepper, and raw onions. Properly, this sandwich is called a mettbrötchen. It may also be sold under the name hackepeter in parts of Northern Germany, but in every place I went to in Berlin, it was called mett. The word "mett" is derived from an Old Low German word for "food," and is the etymological root for the English word "meat." Nowadays, asking for mett in Germany means you want raw minced pork meat.

While the most popular way to eat mett is raw on bread, it may also be made into a sausage called mettwürste. When processed in this way, the meat is dried and cured; although it's still not technically cooked, the end result is similar to an Italian salami, and thus much less foreign to North American palates than mettbrötchen.

The phenomenon of the mettigel

Mett is still quite popular in certain parts of Germany, but it arguably peaked in cultural relevancy during the mid-20th century. The country's post-World War II economic recovery was in full swing, and that meant average Germans could afford to eat a lot of meat after the lean times during and immediately after the war. That's when a special type of mett, the mettigel, became a beloved party food.

"Igel" is German for "hedgehog," and mettigel is just what it sounds like: a little hedgehog sculpted out of mett. Onions (or sometimes hard pretzel sticks) are used to make the hedgehog's spines, while the eyes and face are often crafted with bits of black olive. The dish was a staple at German cocktail parties and other festive gatherings from the '50s through the '70s, but mettigel eventually came to be seen as passé, much like the Jell-O salads and cheese balls favored by mid-century North American hosts. In the 21st century, however, mettigel (and other creative mett sculptures) have seen a bit of a resurgence thanks to people who share their molded meat creations on social media.

Where can you buy a mett sandwich?

While mettbrötchen might be seen as a bit old-fashioned in modern Berlin, it's still quite easy to get, based on my anecdotal experience. Just about every butcher shop seemed to offer mett sandwiches for takeout, even ones that operated out of carts on the street. Bakeries and cafés also commonly sold mettbrötchen as part of their lineup of pre-made sandwiches alongside familiar favorites like ham and cheese. But perhaps the most surprising place I saw mett was in the convenience stores attached to gas stations; it seemed like any gas station in the Berlin area with a large enough fridge sold plastic-wrapped mett sandwiches. You can also purchase just the minced pork by itself from butcher shops or grocery stores to fashion your own mett creations at home. I didn't see mett on the menus of sit-down restaurants very often; it's more of a convenience food.

The mettbrötchen experience is slightly different depending on where you order it from; at butcher shops, they'll typically spread the meat onto a freshly split roll to order, while at cafés and convenience stores, the sandwiches are pre-assembled at the beginning of each day.

Why raw pork might not be as dangerous as you think

Eating raw pork is taboo in North America: Many people still cook their pork well-done for fear of Trichinella worms, but modern commercially-raised pork is very unlikely to contain these parasites, per The Globe and Mail. Additionally, the USDA says that the parasite can be killed by freezing pork to a low enough temperature.

In Germany, the meat used for mett is strictly regulated. It's illegal to sell raw mett the day after it was ground — if butchers want to use the leftovers, they must be cooked. The risk of food poisoning is minimized by making sure that the mett stays cold right up to the point it's served, per Atlas Obscura. That said, my personal experience in Berlin suggested that at least some businesses have a pretty casual attitude toward the potential risks of mett. The pre-made mettbrötchen I bought from a café had been sitting on the counter at room temperature for an undetermined length of time before I purchased and ate it. Nevertheless, it did not make me sick.

Mett is still a little risky

Raw pork may not be the food-safety bogeyman many in the U.S. make it out to be, but eating it does expose you to a bit of risk. Though Trichinella parasites are largely a thing of the past, raw pork consumption in Germany has been linked to bacterial infections like yersiniosis, salmonella, and Campylobacter coli, according to a study in Epidemiology & Infection. I personally would not make mett with commercially-produced U.S. supermarket pork, as there's no way of knowing what bacteria it may or may not have come in contact with during manufacture, packaging, and transportation. The USDA recommends that all ground meat should be cooked to a minimum internal temperature of 160 degrees Fahrenheit.

That said, all raw foods present some risk for food-borne illness, including fruits and vegetables, per the CDC. If you enjoy medium-rare burgers, runny sunny-side up eggs, or steak tartare, you're ignoring the advice of American food safety authorities for the sake of delicious experiences. Granted, U.S. food safety laws are a bit random — the government bans some foods, like lung meat and raw dairy, that are popular in many other countries. Conversely, while the USDA may frown on the consumption of raw meat, it's not illegal. Ultimately, the decision about whether mett is worth the risk is up to you, although it might be best to eat it in Germany, where traditional food-handling practices make it as safe as possible.

What does it taste like?

After eating mettbrötchen a couple of times in Berlin, I can see why the dish has persisted despite food safety concerns and changing culinary tastes. I have enjoyed raw beef many times, which I thought would prepare me for mett, but it turns out that raw pork has a completely different flavor. While raw beef has an iron-rich, minerally taste, pork is much more mild and creamy. Mett reminded me a bit of pâté, as it balanced fatty richness with a savory meaty character, and it was quite soft and tender. The bread rolls used for the base of mett were also very tasty: fresh and yeasty, with a light crumb and a delicately crisp crust.

The basic seasonings applied to the meat — salt, pepper, and onion — were all it needed. The pepper and onion cut through the fattiness of the pork, while the salt enhanced its savoriness. Everything worked together to bring out the natural taste of the meat. It was one of the purest expressions of pork flavor I've ever had.

My one complaint about mett was that it had a tendency to get stuck in my teeth. With no heat to break them down, any bits of connective tissue lodged themselves between my molars until I could get home and floss. However, that minor annoyance was well worth it to sample such a unique and tasty dish.