“Bob would find out how far you could take a work of art and still have a work of art,” the curator Gary Garrels said at the opening of Robert Rauschenberg’s retrospective, a sprawling show of more than 150 works now at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Garrels explained: “He was the great manipulator of images and the great omnivore of images,” saying that the artist’s ability to integrate pop culture into art historical traditions cemented his legacy as a master mid-century conceptualist.

From his Black Mountain College days to his Red Paintings period and taxidermied animal installation phase, Rauschenberg’s creative practice was unorthodox and wildly eclectic. The exhibit is a testament to his eccentric sensibility, and includes a glass vat of bubbling mud, dirt and mold encased in a wooden box, and a taxidermied goat head circumscribed in a tire. The artist called the latter artwork a “Combine” for its dynamic combination of painting and sculptural elements. (Other Combines are comprised of found materials such as winged insects, gold leaf, toothpaste, parachutes, fragments of a Roman fresco, cardboard boxes, snail shells – and most famously, newspaper.)

Excised images and snippets of text culled from newspaper pages recur in many of the mixed-media works. In several cases, all four quadrants of a newspaper are slathered with red paint or gold leaf, effectively brought to their maximalist edge. In Retroactive I (1963), what appears to be a collaged newspaper is in fact a screenprint of John F Kennedy, made shortly before his assassination. Unbeknownst to Rauschenberg, the image would go on to have a deeper, tragic quality. The work is populated by colorful images of a parachuting astronaut, a glass of water, and a close-up of JFK’s hand pointing at the viewer. Taking in this flood of dissimilar images mimics the act of flipping through television channels or a wide-circulation print magazine – both media that defined the cultural moment in which Rauschenberg lived.

In 1953, Rauschenberg secured an artwork from the painter Willem de Kooning and then proceeded to erase sections of it, creating a new pattern from the remaining marks. The resulting work, Erased De Kooning Drawing, challenged notions of authorship and the preciousness of art objects; the artist’s act scandalized many in the art establishment of the time. Advanced infrared scans and the uses of graphite and charcoal have since revealed the original drawing’s contents – abstract figures rendered in a series of gestural marks.

Rauschenberg began experimenting with screen-printing in the fall of 1962 – coincidentally at the same time as the artist Andy Warhol. The two were connected by a mutual friend, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and supported each other’s work: Warhol by sharing a commercial screen-printer contact and Rauschenberg by sharing several original photographs with Warhol to screen-print. This seems as good an example as any to demonstrate how tightly woven and interconnected the downtown art scene in New York was in the 1960s and how interwoven Rauschenberg’s personal life and creative practice were.

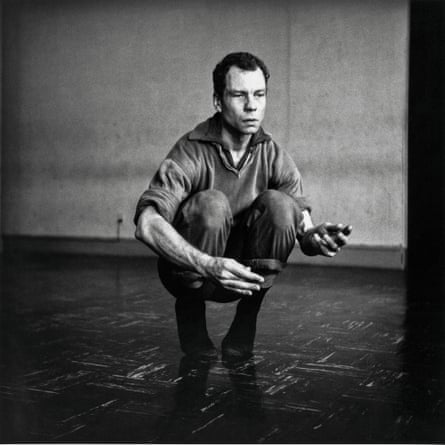

In high-contrast, black-and-white photographs, Rauschenberg captured his famous friends and collaborators: the avant-garde choreographer Merce Cunningham kneeling in a dance studio, the abstract expressionist painter Cy Twombly sitting pensively on a bench, the composer John Cage gazing out from a 50s-era car. In one photo, Rauschenberg captures the artist Jasper Johns, with whom he had a romantic relationship, gazing out somberly from his studio, a bullseye painting and bevy of bottles in his midst.

Haunting photo collages line the final gallery and a photo of Rauschenberg, taken by Dennis Hopper, is especially memorable; plastered across two walls in high contrast black and white, it demands our attention. In the shot, the artist sticks out his tongue at the camera, which is silly and somewhat benign as far as on-camera poses go, but it leaves the impression of a no-holds-barred rebel and rule-breaker.

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg maintained a fiercely cross-disciplinary practice and paved the way for his contemporaries – roving performance artists and conceptual sculptors who refuse to be confined to tedious genre-specific categories. Sure, there are “zombie formalist” painters – a term coined by the artist-critic Walter Robinson to describe a wave of catchy artists who lack substance – but the dividing lines in contemporary art are increasingly blurred.

- Erasing the Rules is at SFMoma, San Francisco until 25 March 2018

![Port of Entry [Anagram (A Pun)], 1998](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/064b8b1c70fc3d455eb034e7beb00cf2b11e00ad/0_0_2100_1468/master/2100.jpg?width=465&dpr=1&s=none)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion