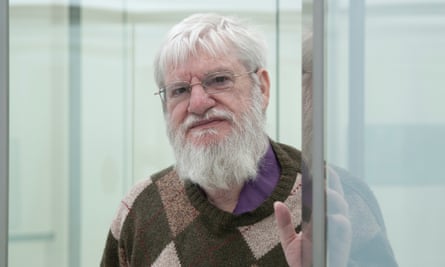

Humour, anthropology and psychoanalytic theory may not be natural bedfellows, but the artist Dan Graham spent more than 50 years utilising all three in a prodigious career that encompassed photography, video, performance and sculpture and strayed into architecture, astrology and music criticism.

In 1966, Graham, who has died aged 79, was travelling on a train from Manhattan to New Jersey when he saw a subtle pattern emerge in the otherwise identikit new housing springing up along the line. Some of the artist’s subsequent photographs of these “tract housing” developments appeared in an issue of Arts magazine under the headline Homes for America, alongside an essay describing an apparent mathematical formula the artist could discern in the architecture. (Graham, unhappy with the editing of both images and text, would later exhibit a series of mock-ups of how he had intended the article to appear.)

“Anarchistic humour is very important to my work,” Graham said in 2009. Homes for America was “pure deadpan humour”, he said. “It’s a fake think piece.” The images were “trying to make Donald Judds in photographs”, he explained, referring to the American minimalist known for his use of repetition and serialisation. The pictures were later shown in various galleries and museums, complete with the written commentary.

The artist became best known for his pavilions, structures of mirror, glass and steel, often curved in labyrinthine spirals, which mimicked the cool aesthetic of modern architecture. The mirrors, Graham said, referenced the psychiatrist Jacques Lacan’s idea of the mirror stage in childhood development. Indeed, many were designed for children: Girl’s Make-up Room (1998-2000) and Children’s Day Care, CD-Rom, Cartoon and Computer Screen Library (1997-2000) provided space for the activities described in their titles.

“The origin of my pavilions dates to the time when I first saw minimal art installed as outdoor public sculpture. It looked so stupid. I wondered how you could deal with putting a quasi-minimal object outside, and also wondered how these things could be entered into and seen from both inside and outside.”

He also termed them “fun houses”, accessible to the whole family. Some have become permanent fixtures: at the Hayward Gallery in the Southbank Centre, London, one is used as an education space, and at the KW Institute in Berlin, Graham designed the arts centre’s cafe. “My early photographs of people’s houses in suburbia, the family situation is also very important. Maybe it was because of my unhappy childhood but I was very conscious of the family … I was an alienated child.”

He was born Daniel Ginsberg to a Jewish family in Urbana, Illinois. Two years later his father, Emanuel Ginsberg, an organic chemist, changed his name to David E Graham after antisemitism blocked various employment opportunities. The whole family followed suit. Dan described his father as abusive and his mother, Bess, an educational psychologist, as “cold and very intellectual”. Graham suffered from what he described as “almost a schizophrenic breakdown” aged 13, which resulted in him being administered antipsychotic drugs. “All artists have a special relationship with their mother,” Graham said. “My mother was in denial of the body, and my work became about the body.” Miserable at school, aged 14 Graham turned to reading, starting with science fiction and moving on to Jean-Paul Sartre, the anthropologist Margaret Mead and, later, the German theorist Walter Benjamin.

In 1961 he started spending most of his time at a friend’s house in Manhattan and, aged 23, he joined two others “who wanted to social climb”, and opened an art gallery on Madison Avenue. The John Daniels Gallery lasted less than a year, and lost the founders money, but staged Sol LeWitt’s first solo exhibition as well as group shows featuring Judd, Dan Flavin and Robert Smithson. Forced to live back at his parents’, paying off the debts through writing essays and articles on his peers, as well as subjects including the television persona of the entertainer Dean Martin and the paintings of President Dwight Eisenhower, Graham started creating his own art in 1966.

One early work, Schema, consists of a series of A4 sheets summarising the texts Graham had published by word count, number of nouns and adjectives, percentage of the page covered by text, and other such statistics. His first solo exhibition took place at the John Gibson Gallery, New York, in 1969; the following year he was invited to Canada to teach at the Nova Scotia School of Design in Halifax. “I had no money. I never had any money in my life, and I wanted to make film and video … they had equipment.”

Featuring his students, Graham’s 1972 performance work Two Consciousness Projections(s) sees a woman sitting in front of a television that relays her own image, a live stream from the camera being operated by a man who is standing behind the monitor. Speaking at once, the woman is tasked with describing her mind while the man only narrates the scene he can see through the lens of his camera. “The man was like an old Freudian analyst, like Sigmund Freud, who thought the idea was the man knows everything,” Graham said. “And the woman is just a subject. [The audience], eventually they identify with the woman, because obviously, she was able to talk about herself.”

Mirrors first entered his work three years later with Performer/Audience/Mirror, also made in Halifax, in which a man describes his reflection in excruciating detail before an audience. Public Space/Two Audiences, produced for the 1976 Venice Biennale (the first of three times that he participated), divided a gallery into two parts with a soundproofed glass partition, with a mirror on the far wall, so that each group could silently view the other as well as their own reflection.

His interest in art was “a hobby” he said, but he was deadly serious on other subjects, most notably rock music and astrology. His 55:27-minute film Rock My Religion (1982-84), made up of collaged found footage, posits gig-going as an ecstatic religious experience: “While individual rock heroes (singers) are unrepentant sinners, the rock group is more like a self-sufficient commune,” the narrator intones at one point.

For the 2006 Whitney Biennial he collaborated with the artists Tony Oursler and Rodney Graham on Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30, a rock opera puppet show. Sometimes refusing to work with people if their star sign did not suit, Graham wrote an occasional column on the horoscopes of famous architects for Domus magazine.

His work was shown at the Documenta festival in Kassel, Germany, five times from 1972 onwards and was the subject of a travelling retrospective, which opened at the Whitney Museum in New York in 2009. His first public pavilion was commissioned for the Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago in 1978 with over 50 more following, including Turner Contemporary in Margate in 2013, and in the courtyard of the Lisson Gallery in London in 2018.

He is survived by his wife, the artist Mieko Meguro, a son, Max, and a brother, Andy.

Daniel Graham, artist, born 31 March 1942; died 19 February 2022

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion