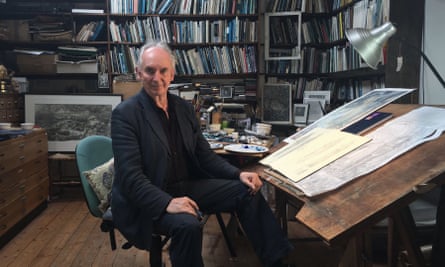

For artist Alan Lee, nature has always provided a gateway to other worlds. Now 71, Lee remembers growing up in Uxbridge, on a council estate that bordered a wilder landscape. It was what you might call a liminal childhood – on one side, the recently minted avenues and structures of social housing, on the other, “a short walk into this strange landscape of canals and fields and woods”.

It’s that sense of crossing from one world to another that has informed his work, especially his association with JRR Tolkien’s Middle-earth, which has formed a large part of Lee’s oeuvre over the past quarter of a century.

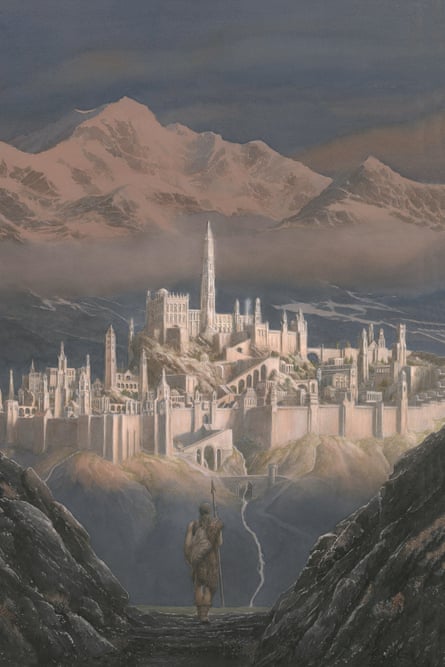

His latest project is just released: the third “rediscovered” Tolkien novel, The Fall of Gondolin. Edited by Tolkien’s 93-year-old son Christopher, this volume – like its predecessors, The Children of Húrin and Beren and Lúthien – has been assembled from the author’s detailed notes. Tolkien, who died in 1973, always intended to publish these prequels to the main Lord of the Rings trilogy.

It’s likely to be the last of the unreleased books, according to Christopher Tolkien. If it is, it’s a sumptuous volume to end on, illustrated with Lee’s black-and-white ink drawings and full-colour watercolour plates.

Lee first encountered Tolkien aged 17 while at Ealing Art College. A fellow student gave him a copy of the first in the Lord of the Rings sequence, The Fellowship of the Ring. “I was just amazed,” he says. “I had grown up reading a lot of folklore and mythology, and this had elements that I recognised – elves and dwarves and dragons and magic rings. I just devoured it.”

Lee left his art and design course, “disenchanted”, after a year; he had been warned at school in Ruislip not to go to Ealing “because it was full of beatniks”. Now, he thinks he was too young to appreciate the sometimes outre methods of his tutors. He recalls one morning spent making paper tubes, standing them on end, pushing them over and standing them up again, to provide a photo opportunity for a photographer, who walked in a couple of hours later. It was Lord Snowdon.

Lee took a year out to work as a graveyard gardener, a job that bridged nature and civilisation in the way his Uxbridge childhood had, and also later fed into his Middle-earth work. “Walking through the gates of the cemetery was like stepping into a different world,” he recalls. “It was a portal to a strange realm of overgrown graves and trees.”

While he was working the graveyard shift, the entire faculty at Ealing College had departed and been replaced, and when he returned to finish his course he found a much staider atmosphere, heavy on graphic design and advertising. But reading The Lord of the Rings had reignited his childhood love of folklore and myth. “While everybody else was working on campaigns for Volvo, things like that, I was quietly sitting there illustrating ancient Irish folk tales,” he says.

After leaving college, Lee worked on magazines like Reader’s Digest and Women’s Own, before graduating to book covers. His best-remembered covers adorned Fontana ghost-story anthologies and Alan Garner novels, including The Weirdstone of Brisingamen.

Lee also created a series of illustrated books on fantasy, which came to the attention of Jane Johnson, an editor at Allen & Unwin and responsible for the Tolkien list. She showed his work to Christopher Tolkien, who agreed that Lee was the perfect choice to illustrate a lavish edition of The Lord of the Rings, to be released in 1992 to mark the centenary of Tolkien’s birth.

That was the start of Lee’s 20-year association with Tolkien’s world. What would the 17-year-old art student think, if Lee could go back and tell him that he would one day illustrate the series? “I would have been amazed,” he says. “At that age, I didn’t even think that illustration could be a proper job, or at least, not for me. I grew up on a council estate, I failed my 11-plus exams.”

If that would have amazed the teenage Lee, what came next would have blown his mind. Lee had just moved to the edge of Dartmoor when he was contacted by the director Peter Jackson, who was about to adapt The Lord of the Rings for film and wanted Lee on board to help create the look of Middle-earth. Would he be free to go to New Zealand for six months?

“That turned into six years,” Lee laughs. “I lived out there while all three films were done. I was probably the last member of the crew left there, doing the final promotional art work.”

New Zealand was another gateway that has haunted his life. “It has a real otherworldliness,” he says. “Perfect for Middle-earth – such a mixture of alpine landscapes, volcanic scenery, heath and rocks.”

After returning to Devon, Lee illustrated the first of Christopher Tolkien’s edited books based on his father’s early work, which became The Children of Húrin, published to great acclaim in 2007.

However, Lee barely had time to catch his breath before director Guillermo del Toro came knocking, looking for his help in the world of The Hobbit. (Del Toro would later forfeit the project to Jackson.) “They wanted me back in New Zealand for six months,” Lee says. “Nobody at that time mentioned it was going to be a trilogy, though – I ended up staying for another six years.”

With no more films on the horizon, Lee is happy to be back in his studio on Dartmoor, where he predominantly works in watercolours and experiments with digital techniques he learned in New Zealand. He has just done a fairly exhausting UK tour to promote The Fall of Gondolin, taking in two cities a day for talks and signings.

He’ll be glad to return to Devon – another of those gateways – where he looks out from his converted barn on to the untamed landscape of Dartmoor. He’s got another book to work on: a Hobbit sketchbook featuring his work on both films and books.

“I have to admit,” he says, “I’m at my happiest when I’m sitting in my studio with a brush in my hand.”

- The Fall of Gondolin by JRR Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien and illustrated by Alan Lee, is out now from HarperCollins.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion