When Dene Hofheinz Anton was a young girl in the early 1950s, her father would carve time out of his busy schedule as the mayor of Houston, Texas, to take her to see the Buffaloes, the city’s minor-league baseball team. Mayor Roy Hofheinz had previously served in the state legislature and also as the top official in Harris County, which includes Houston, and his significant status meant he was intimately connected with the goings-on of the city.

Baseball games provided rare bonding time for the politician and his only daughter. In the stands at Buffalo Stadium, the pair would endure heat, humidity and mosquitoes to watch games together, but too often their bonding time was cut short by rain. For young Dene, each rained-out game meant less time with her father.

“One night I just casually said, ‘Daddy, why can’t we play baseball indoors?’” she recalls. “In my 10-year-old mind that seemed like a solution. I was only thinking in terms of, ‘Then we won’t get rained out, and then I get to spend more time with you.’”

Hofheinz saw the wisdom in his daughter’s question. Over the course of the next decade he gathered political, architectural and engineering resources – as well as roughly $31m in public funding – and built what was then the world’s largest indoor stadium, the Harris County Domed Stadium, better known as the Astrodome.

On 9 April 1965, the $37m, county-owned Astrodome opened to the public, with Houston’s business elite comfortably seated in its innovative luxury boxes, its climate controlled to 72F (22C) and its grounds surrounded by thousands of parking spaces. The Astrodome’s first event was an exhibition baseball game between the Houston Astros and the New York Yankees, which president Lyndon B Johnson attended. More than 20 US astronauts from the nearby Nasa centre simultaneously threw out the ceremonial first pitch, and later baseball legend Mickey Mantle hit a home run. The evangelist Billy Graham soon declared the stadium the “eighth wonder of the world”.

Today, 50 years later, the space-age Astrodome sits shuttered, locked behind a fence, riddled with asbestos and used only for storage. Victim to an era it almost single-handedly created, in which teams and fans leave behind old stadiums for flashy new ones, the Astrodome has been idle since 2008 – the Astros moved into a newer stadium downtown in 2000, and the Oilers American football team played there from 1968 before leaving Houston for a newer stadium in Tennessee in 1996.

Dozens of ideas for what to do with the empty building have since been proposed, from hotels and theme parks to ski slopes, but none have mustered the support nor the tens – or more likely hundreds – of millions of dollars it would take to turn those ideas into reality. Demolition alone could cost up to $80m. A November 2013 bond election in Harris County to raise $217m in public funds to refurbish the building into a multi-use facility they called the New Dome Experience failed, with 53.5% of voters against the idea. Previously hailed as an architectural marvel, Houston’s Astrodome now faces an uncertain future.

But now, a new plan gathering support among local politicians, stakeholders and preservationists could save the Astrodome. Proposed by an expert panel convened through the Urban Land Institute, this “vision for a repurposed icon” calls for grass fields, trees, play equipment and exhibition spaces in what could be one of the largest indoor parks in the world.

Seeing the Astrodome in person, it’s hard to imagine such a large building could be so ignored. Its sword-shaped columns tower up almost 100 feet, and grey concrete walls careen around its nearly half-mile circumference. Above, the dome slopes up close to 200 feet high, its thousands of Lucite skylight panels bulbing out geometrically, like the eyeball of a fly.

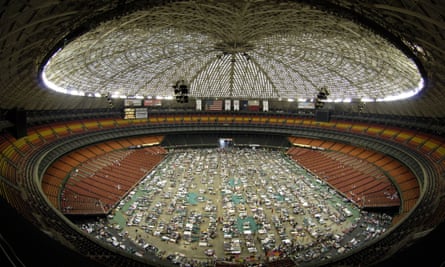

Inside, there’s more than 350,000 sq ft of area from wall to wall, and with its playing field recessed 30 ft below ground level, an 18-storey building could stand up inside. At its fullest capacity, for its farewell concert in 2002 by the country star George Strait, more than 68,000 people paid to get inside.

Even after years unused, the Astrodome remains Houston’s most-recognisable icon. The fourth most populous city in the US with roughly 2.1 million people, Houston suffers from a reputation associated with unchecked sprawl and car-dependence. It is the largest US city with no zoning regulations. But it’s also one of its most ethnically diverse big cities, and one seeing a rising demand for residential space in the core of the city – inside the “610 loop”, a nearly 100 sq mile area ringed by Interstate 610.

Downtown is in a building boom, and a burgeoning light-rail system is slowly offering new ways to get around at least some segments of the gigantic city. (For a recent nighttime rodeo event, a train emptied almost completely at the stop on the edge of the Astrodome complex, just outside its still-packed 26,000-space parking lot.) The city is densifying and changing, yet transportation officials are also planning to complete a 180-mile-long outer beltway 25 miles from the city centre that would travel through seven counties, pushing the edge of the region’s sprawl even farther.

Houston is perhaps the most American of US cities, straying far from the strict European models of citymaking found so frequently elsewhere. For many, the Astrodome exemplifies that uniqueness, symbolising not just a moment in time or an architectural feat, but a new type of city living.

“When it was built, it really did represent a lot of what was great about Texas and Houston,” says James Glassman, who runs Houstorian, a website about the city’s history. “Whether it was Nasa and the space industry developing, or the air-conditioned model, the car culture – all those things that came out of the 1950s and 60s were put right there into the Astrodome.”

Glassman is one of many Astrodome enthusiasts who’ve rallied to save it by celebrating its reputation. He sells Astrodome T-shirts on his website, and plans to produce 3D-printed Astrodome cufflinks for its 50th anniversary. More than 7,000 people lined up outside the Astrodome in 2013 for a fundraising auction that sold off hundreds of pairs of stadium seats, memorabilia and even chunks of AstroTurf, netting the county more than $800,000. Near downtown, the 8th Wonder Brewery recently opened an Astrodome-themed taproom, complete with seats from the stadium auction and the dome’s arching truss painted below its warehouse ceiling. The Astros are honouring the 50th anniversary at their 18 April game by giving fans small replicas of their former stadium.

But this nostalgia isn’t necessarily widespread. Glassman says Houstonians have a “history problem”, likening it to amnesia. “We’re such a forward-looking city that sometimes great, older properties or sites get neglected or just knocked down altogether,” he says.

Through a 2015 lens, the Astrodome is arguably just another stadium. Despite being the first large indoor stadium, the first to use AstroTurf, the first to entice big spenders with luxury boxes, the first to precisely control the climate and conditions of play, it’s now just one of hundreds worldwide that have done the same and more. The Houston Chronicle’s NFL writer, John McClain, summed up the ambivalence of many people in this March 2013 Twitter post: “If they can tear down Yankee Stadium and the Boston Garden, they can demolish the Astrodome. That’s what pictures, video and books are for.”

The prospect of demolition – raised repeatedly in recent years – disturbed many in Houston and beyond, and spurred local preservationists to come to the Astrodome’s defence. Cynthia Neely, a gregarious, gold-and-silver-haired Houston transplant, is one defender. Sitting on a bench outside the Astrodome on a hot and humid spring day, with carnival rides from the annual Livestock Show and Rodeo swinging in the background, Neely says the first thing she did after moving to Houston in 1980 was take a $1 tour of the Astrodome.

After its closure she worried officials would demolish the building, which its lack of historic status could have allowed with little difficulty. Along with fellow preservationist Ted Powell, Neely submitted an application in 2013 to include the Astrodome on the National Register of Historic Places, unbeknown to county officials. That process requires a building’s owner to apply for recognition and, as a taxpayer in Harris County, Neely is technically one of the Astrodome’s owners – which, she says, “is how I caught them off guard”.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation got involved, naming the Astrodome one of “America’s 11 most endangered historic places” in 2013. Beth Wiedower, who heads the National Trust’s Houston office, says the Astrodome is at an awkward age where people don’t think it’s old enough to merit preservation. It’s a problem that’s faced other 30- to 50-year-old buildings, despite being celebrated pieces of architecture. Bertrand Goldberg’s brutalist 1975 Prentice Women’s Hospital building in Chicago began demolition in 2013, for example, and Paul Rudolph’s modernist 1967 Orange County Government Center in New York was recently slated for demolition. “It’s psychological,” Wiedower says. “Once a building is past the 60-year mark, it’s easier to get people behind preserving it.”Demolition was still an option as recently as last summer, when the Texans and the Livestock Show and Rodeo announced a proposal to tear down the Astrodome to its columns and build, in its centre, a scaled-down, 25,000-square-foot version of the stadium they called the Astrodome Hall of Fame.

That proposal didn’t gather much traction, but it got Harris County Judge Ed Emmett thinking. A former state legislator and member of the George HW Bush presidential administration, Emmett has served as the county’s chief-executive since 2007, the year before the Astrodome was shuttered. He’s been a Houstonian since high school in 1966, and lived less than a mile from the stadium – “If you climbed the tree in our front yard you could see the Astrodome,” he says. Now, as the top official in charge of the county-owned stadium, it’s his responsibility to figure out what to do with it. At times that’s been a burden, but Emmett now sees it as an opportunity.

“If you were to start from scratch today and try to build the Astrodome, I don’t think the voters would approve it,” Emmett says. “But it’s an asset that we already own. It already belongs to the taxpayers. Why not put it to some better use?”

Throughout his tenure, Emmett has fielded dozens for projects including hotels, water parks and movie studios. One proposal even suggested flooding the recessed playing field to reenact naval battle scenes. “Obviously that wasn’t going to work,” Emmett laughs, “but it was at least inventive.”

After so many failed ideas for private redevelopments and the county’s own attempt to sell the idea of the “New Dome Experience”, Emmett decided to call in some experts. The county contacted the Urban Land Institute and commissioned a panel of real estate developers, planners, architects and politicians to visit Houston in late 2014 and offer advice on the future of the Astrodome.

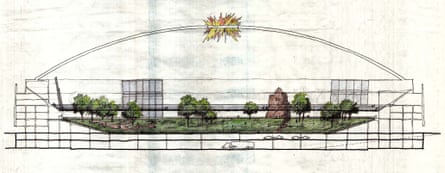

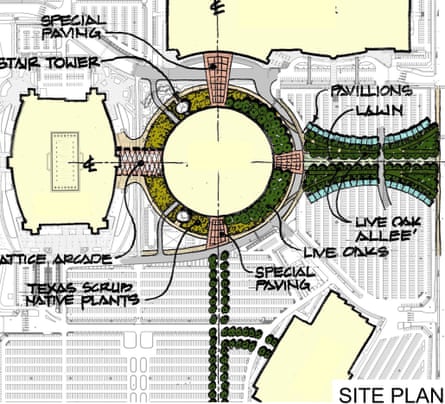

In December, the panel released preliminary recommendations, which called for the Astrodome’s interior to be gutted and for the building to be turned into a massive indoor park. Pastel drawings of the proposed park space show grass fields, meandering pathways, full-sized trees, carnival rides and exhibition spaces. The park would be a covered and climate-controlled space available year-round – an oasis in a city where humidity is often in the 80% range and temperatures can leap or fall 40 degrees from one day to the next. Crucially, the report also includes ideas on how such a project could be funded and made financially sustainable.

“I think we were able to produce a plan that was quite specific. It certainly is conceptual but it has a lot of substance to it, and I think that’s an easier thing for people to understand,” says Wayne Ratkovich, a Los Angeles-based developer who chaired the panel. “It has more allure to it, more excitement to it than simply a verbal idea that says, ‘Let’s have this bond measure and we’ll figure out what to do with the Astrodome.’”

“Preservation is no longer about freezing something in time, it’s about giving it new life,” says Stephanie Ann Jones, executive director of Preservation Houston, which has been lobbying on the Astrodome’s behalf for years. Officials foresee the park being used for football tailgate parties, concerts and large events, and as part of the fan experience when Houston hosts the 2017 Super Bowl – something of an internal deadline to get renovations going.

“In two years we’re hoping to have something,” says Edgardo Colón, chairman of the Harris County Sports & Convention Corporation. “Is it going to be a full-blown park? Probably not. What you see on day one is not necessarily what you’ll see in year five or year ten.” Cushioned stadium seats from the Astrodome sit in the conference room at his law firm’s offices, and renderings of “the New Dome Experience” are still on display. He expects the indoor park plan to be finalised and begin implementation within the next year. Fundraising is underway. Another Astrodome seat sale is being held as part of its 50th anniversary celebrations.

The park’s cost depends on an as-yet-undecided design, says Emmett, but it’s almost certain to cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Colón is confident that some funding can be raised through philanthropy, but public funding, likely a bond, would also be required. It’s an uneasy prospect, given the last Astrodome bond’s failure, which, Emmett notes, didn’t even have an organised opposition. “You have to really sell it. And we understand that whatever we do next time on the dome is going to take an all-out effort.”

To help build his case for a park, Emmett recently travelled to Brandenburg, Germany, to visit Tropical Islands Resort, a 700,000 sq ft indoor beach park built within the hangar of a bankrupt airship company. He’s hoping to bring back lessons about how the park works, and how the skylights in the Astrodome can be tweaked so that grass and other plants can thrive.

For Dene Hofheinz Anton, there are echoes in this trip of her father’s Astrodome-related fact-finding missions during its development, visiting Rome to learn about the Colosseum and the dome-shaped Palazzetto dello Sport basketball stadium. “Judge Emmett is, in his own way I think, kind of inspired by my dad,” she says.

If the current county judge is taking lessons from the predecessor who built a stadium that, in many ways, changed history, it’s a sign that the Astrodome may have another life ahead. Hofheinz Anton, who essentially came up with the concept of the Astrodome, wants it to reopen as soon as possible so that new generations can experience a building she loves so much. “You go in there and look up at that ceiling and you’re just overwhelmed,” she says. “Everybody deserves to walk in there one time in their life.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion