Tommy Lee Jones strides into the room and is, for a moment, unrecognisable. The hair is neatly combed and he wears a grey pinstriped suit with a blue shirt and tie, black socks, black brogues and distinct air of civility. He could be an accountant. Or, even more heretically, an English gentleman.

He has just returned to California after a stint filming in London and the place seems to have rubbed off on him. “I’m very comfortable in London,” he says. “I lived for about five weeks in a house in Chapel Street in Belgravia.” He pronounces it Belgraahvia, suggesting cocktail evenings with posh folk in the embassy district.

“I enjoy the island. I have long, enduring relationships with people there.” Jones makes a cheerful confession. “Actually, by now I’ve got a tailor on Savile Row.” He plucks at his lapels. “This one was not made there but all my suits in the future will be made on that street. It feels kind of nice.” He grins. “I’m kind of pleased with myself that I’ve got a tailor on Savile Row. I’m 68 years old. I deserve it.”

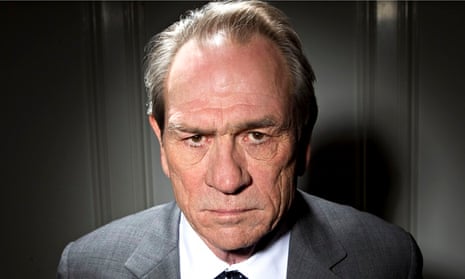

For an actor seldom seen out of jeans and boots, and best known for playing badass lawmen and killers in the darkest corners of America’s psyche, the role of English gent seems incongruous, and the illusion duly dissolves. As the sun sets over Hollywood, casting shadows across the Beverly Hills hotel room, Jones sprawls on a sofa, orders sake and spends the next hour showing why he is one of the most interesting, revered and feared figures on the cultural landscape.

There is the face. A craggy, weathered testament to the elements that could stop a clock. There are the black eyes, once compared to tiny oil wells, and the massive, leathery hands that erupt from his sleeves. There is the voice, a crackling instrument coated with the dust and twang of an an eighth-generation Texan. And there is the flinty personality, sharp, jagged, unyielding.

Jones won a best supporting actor Oscar in 1993 for playing the relentless marshall who pursues Harrison Ford in The Fugitive, but also etched his mark playing a sheriff in No Country for Old Men, Agent K in the Men in Black series, murderer Gary Gilmore in The Executioner’s Song, and a grieving father investigating troubled Iraq war veterans in In the Valley of Elah. Some think his abolitionist congressman Thaddeus Stevens, an Oscar-nominated role, stole Lincoln from Daniel Day-Lewis. There is a sandblasted rawness few others match because Jones is that rare thing, an authentic loner. His intensity imbues roles with a moral compass even when playing the bad guy.

None of which really prepares you for his latest incarnation: the quasi-feminist. Jones has directed, co-written and stars in a subversive western, The Homesman, which explores the female condition in the frontier harshness of 1850s Nebraska. Hilary Swank plays a resilient, lonely singleton who enlists Jones’s crabby claims jumper to help her escort three mentally ill women back to civilisation. “Our film is the inverse of the conventional western,” says Jones. “It’s about women, not men; it’s about lunatics, not heroes; they’re travelling east, not west; and we have a different perspective on what has come to be called manifest destiny.”

The film, his fourth as a director, veers between brutality, black comedy and compassion. It has won rave reviews. It has also swung a lantern over forbidden terrain: Jones’s personal beliefs. In The Homesman, based on Glendon Swarthout’s novel, he has put female suffering and fortitude at the heart of a quintessentially masculine genre.

Sexist injustice, he says, continues to this day. “I don’t think there’s a woman in the readership of the Guardian, not one, who hasn’t been objectified or trivialised because of her gender at one time or another. And that’s really what our movie is about.”

So is it a feminist movie? A pause. He chooses his words carefully. “It would not be unfair to call it that but I’m not looking for labels.” It seems he will elaborate but doesn’t. A prolonged silence ensues.

No, Jones does not look for labels. And if he thinks he detects one lobbed in the guise of a question about his personal convictions, those black eyes petrify it mid-flight with a basilisk glower.

The son of an oil driller and beauty shop owner has a bookish, cerebral streak that won him a scholarship to a Dallas prep school and Harvard, where he roomed with Al Gore and obtained a BA in English literature, writing his senior thesis on the mechanics of Catholicism in Flannery O’Connor’s books.

But apart from a speech at Gore’s 2000 Democratic presidential nomination, the cowboy of the new west, as he has been dubbed, has masked his political beliefs. Liberal or conservative, libertarian or paternalistic, doveish or hawkish, it has never been clear.

Jones detests intrusion into what he considers his private sphere. He once alluded to a “psychically horrifying” childhood defined by drunken parental arguments, but it was fleeting public candour. His three marriages, 3,000-acre ranch outside San Antonio and passion for polo remain off-limits topics.

He maintains opacity with legendary brusqueness – some say bullying - which has intimidated peers, fans and interviewers alike, reducing some to tears. Sting, who worked with him on Stormy Monday, called him “monstrous”. Jim Carrey, his Batman Forever co-star, said he “scared the hell out of me”. Questions he dislikes, such as whether he believes in aliens, or his friendship with Gore, can prompt walkouts or overturned furniture. His scowling visage during a Golden Globes ceremony prompted an internet meme comparing him to Grumpy Cat.

Like his character Harvey “Two-Face” Dent in Batman, Jones is condemned to duality: he scorns the celebrity game with acidic disdain yet must play it, up to a point, to promote his work. “There are certain contractual obligations and one does the best that one can do,” he says stiffly when I ask about press interviews. It is a cue for him to drain his sake and take a refill.

When he ordered the bottle I had hoped sharing a drink might stoke conviviality but as the interview wears on it is clear the booze is to sustain him through the ordeal. Since he’s promoting a film that is a labour of love and potential Oscar contender, Jones does his best to be polite. The herculean effort wreaks a toll. As one question follows another he fidgets, criss-crosses legs, examines my phone, broods, winces, tugs his hair, yanks it up, then down, then to the side, momentarily creating a mad professor effect which would be funny were it not for the death stare.

With foreboding I edge on to forbidden terrain. The film takes a bleak view of US expansionism, depicting some pioneers as cheats, brutes and bandits, I say. He nods.

“It’s about people living on the cutting edge of what is sometimes called manifest destiny. What is the price we pay for believing that God meant for us to own everything between Massachusetts and California? People still believe it, and schoolchildren are still taught that there is almost a divine right for the United States to hold the land that it does today.”

If the story’s feminist angle has contemporary resonance, I ask, might there be also be a resonance in relation to US foreign policy post 9/11? The voice lowers and he leans forward to emphasise each word: “I did not come here to talk about US foreign policy in the Middle East, and I will not do it.”

The Texan twang vapourises other efforts to elicit opinion. Of US voters’ midterm gloominess: “I’m not going to make a broad political statement. There are some discouraging headlines in newspapers.” Of border control and immigration reform – a topic in The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, which he directed in 2005: “There seems to be a lot of people worried about it.” Of global warming – an intriguing topic since he fronted ads for for the Texas oil and gas industry but also made an eco-minded expedition to Antarctica – he says only: “I think any thinking person should be worried about climate change.”

I mention a scene in The Homesman that feels allegorical: his character, George Briggs, burns down a hotel along with its rapacious owner, played by James Spader. Jones nods. A commentary, perhaps, on capitalism? He evades the question with a discourse on frontier business practices. Pressed, he replies: “It speaks well for the movie that you’re thinking about these things.”

As a Dubliner I ask why Spader’s character was Irish. Jones answers by asking whether I believed the accent. In truth I found it a bit shamrocky Oirish but mumble it was fine. Jones nods, approving. “I think Jimmy is a wonderful actor. He’s a good pal.”

Another friend and collaborator, Oliver Stone, has expressed interest in making a documentary about Vladimir Putin. If it were a biopic I ask who should play Russia’s president.

“I don’t know who in the hell would play that guy.”

How about you?

“No.”

Why not?

“He’s a Russian.”

But it could be shot in English.

“You think so? Hm. I don’t know anything about him.” Jones seems about to close the topic, then muses on the notion. “He seems to be somewhat ... malevolent. But I don’t know anything about him, much, other than I don’t trust him.”

Jones praises Stone, who directed him in JFK. “I have the highest respect for Oliver. I would be really interested to see a screenplay at any time. Anything of his work would be of interest to me.”

Asked about other peers he admires he turns coy. “I don’t want to start naming names of living American directors because I’ll leave someone out and they’re friends.”

He does, however, observe that with the exception of the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men and The Sunset Limited, which he directed, Hollywood has bungled adapting the novels of his friend Cormac McCarthy. “I don’t think he’s been served very well by the movies so far.” The Road, directed by John Hillcoat, was not entirely successful, he says.

Out of the blue he actually chuckles – a pleasant, gurgling sound, let history record – when I ask about him and McCarthy being dubbed “the Texas apocalypse intellectuals” for weaving big, dark themes with American west narrative. “Really? Where did you hear that?” (A 2011 Newsweek article). The idea amuses until I make the mistake of asking if it’s a fair moniker. Instantly he bristles. The English lit grad senses a cousin of label. “I would object to any moniker.”

Two years shy of 70, Jones confesses to insecurity about job offers, saying he hopes to be able to continue acting, writing and directing. “I don’t want to end my career.” Action roles show no sign of drying up. In London he was shooting Criminal, a thriller with Ryan Reynolds, Gary Oldman and Kevin Costner. In January he will be in Thailand starring with Jason Statham in Mechanic: Resurrection.

There is one area which holds little appeal for the great grouch: television. The small screen’s supposed golden age of The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad and True Detective is passing him by, and that’s just fine. “I probably watch less than one hour of television a week. And when I do watch television it’s usually a football game. Sometimes I’ll watch a news broadcast for a few minutes. Otherwise I don’t have time.”

Directors such as Steven Soderbergh, Cary Fukunaga and Jonathan Demme have migrated to television, as have actors such as Matthew McConaughey, Woody Harrelson and Sean Bean, but Jones is in no rush to follow.

As a director he is fanatical about capturing a certain look and television, he feels, is a medium of compromise. “Most of those things are so poorly lit. And they are limited a lot by their tight schedules. They have to shoot so much material and they have to shoot it so fast.” He shakes his head, appalled at the cinematographic sins. “The lighting is often rather ...” He pauses, searching for the right word. “Gross.”

The interview ends. Jones exhales, smooths his hair, rises and stretches. A luminous moon hangs over Hollywood. We shake hands. A parting question. Has he ever enjoyed an interview? “Oh yeah, sure.” Any one in particular? A pause. “No.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion