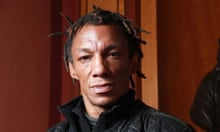

When we meet, at his record company's office in south London, the first thing Tricky tells me is that he hasn't smoked a joint in three weeks. He's intrigued by his willpower. It is the longest period of abstinence he has managed, he says, since he was 15. The original trip-hopper is now 42. Sitting on the edge of his seat, with a cup of tea, next to his latest singer-muse, a young Irishwoman called Franky Riley, he gives the impression that the world is looking unusually sharp-edged. As a result, his fighter's face, under its dreadlocked mohican, seems invigorated and slightly puzzled.

Is he thinking of giving up for good?

"I don't really want to smoke," he says, "or maybe just one in the evening. Since I was a kid, from when I wake up in the morning I smoke until I go to bed and I'm never, you know, present. I'm always not there. So I just thought: it needs to stop."

This desire for clarity is part of the ongoing quest for self-knowledge that began for Tricky when he was seven years old, still called Adrian Thaws, and was trying to make some sense of the insanity that had attended his life to that point. His father had left home before he was born, his mother, Maxine Quaye, had killed herself when he was four and he had been brought up in "the white ghetto" of Knowle West in Bristol mostly by his grandmother, who was happy for him to watch horror movies with her all night rather than going to school. When his gran was working she would drop him off at her mother's house, which was where Tricky started to write: "It was pretty hard-core at my great-grandmother's place: no TV, no books, not much furniture, concrete floors. I'd pick up a pencil and a piece of paper and just get out whatever was in my head."

What was in his head, even then, was a curious relationship with violence, seen at one remove, a tense mix of vulnerability and aggression. "I had seen my uncle stab my other uncle in the house when I was about six, seven. For a child, it's not so much scary, it's surreal; there was a lot of fighting in my great-grandmother's house; you'd go there and then someone would meet up and there'd be a fight; I've seen my uncles fight in the street, I've seen my grandmother fight in the street, it becomes normal."

He began "writing properly", he says, at about the time he started smoking dope – as "self-medication" – and going clubbing in Bristol, often in a dress, and getting into fights of his own. At the time, he suggests, smiling at the idea, "I thought I was a rapper." Tricky was never that, quite. Always more of a whisperer or a ranter or a rasper, master of not one voice but many. Those voices in his head first became public when he collaborated with Massive Attack on their 1991 debut album, Blue Lines. Four years later, it found its full, paranoid, mesmerising expression on Maxinquaye, his "voodoo" homage to the mother he never knew, ventriloquised in the honeyed voice of his ex-lover (and mother of his daughter) Martina Topley-Bird and cut with his trademark dreamy undercurrent of angst, menace and seduction.

The album prompted universal and hyperbolic critical acclaim, the most memorable element of which was David Bowie's 2,000-word paean in Q magazine, a fantasy in which Bowie acknowledged not only the arrival of a proper heir to his own shape-shifting, but also recognised that his own games might be up. "Here come the horses to drag me to bed," Bowie concluded. "Here comes Tricky to fuck up my head."

In the 15 years since that album and the attendant global notoriety, Tricky has tried on multiple lives for size. He had a go at megalomania; his second album was called Nearly God, a quote from one interview, and he seemed plagued with satanic thoughts and fears for himself. Having always felt most at home in a studio, he became a manic and highly reluctant live performer, often doing whole shows entirely in the dark. He developed paranoid vendettas against journalists and rival musicians and when his relationship with Martina ended he lived – to extremes – and worked – eccentrically and hard – first in New York, which he left after 11 September, to try life in small-town New Jersey for a while. This wasn't for him: he got scared of the dark woods, the lack of street lighting ("You don't know what's out there," he observed, with feeling). Moving to LA, he got into spats with labels and producers and found his obsessive workaholic studio routines frustrated. He carried many of his demons with him, along with the West Country vowels that give an incongruous Somerset lilt to his wilder urban tales.

"The thing is," he says, "you have really got to be disciplined in LA. And I found that hard."

Tricky's idea of discipline is quite a loose one.

"For one thing," he says, "I started getting into the gun culture, shooting at galleries and in the desert and all that. One time I did this stupid thing of leaving a gun under my bed. It was an Uzi. The cleaner used to come to my house and bring her kids; unfortunately one kid found the gun and fired it when I was out. Luckily, I was in a restaurant because when the police came I could prove I'd been there and not fired the gun myself."

The problem was the bullets had gone through the walls of his apartment into the next-door neighbour's living room. "They weren't that happy about it," Tricky says and shakes his head, as if slightly put out by this reaction. "So what it comes down to: you've got to be disciplined there, you know what I mean?"

Since then, it seems, he has been experimenting with that truism that you spend the first 40 years of your life escaping from home and the next 40 trying to return. He has lived since 2008 in Paris, partly to be nearer to his daughter, Mazy, who is now 15 and lives with her mother in London. Moving to the capital full-time, he says, would be a step too far – "Sometimes my family [brothers and cousins and uncles; his gran] can get a bit much." Paris allows him to shut the door. He doesn't speak French, he just points. And he has a studio in his apartment, in which he makes his layered mischief. Being in Europe seems to have made him curious again about where he came from, who he is. His last album, 2008's Knowle West Boy, was a kind of return to first principles and rooted in autobiography. "To go forward," he says, "you have to go back and when I write, all I've got to write about is my past, really."

His new, eclectic and compulsive album is Mixed Race, a reference to what he sees as the single biggest influence on his life: the fact that when he sat around the dining table at home, there was every colour of skin under the sun, "and I never noticed". This mix showed itself most keenly in the music he absorbed. "When I was 12 and my cousins Mark and Miles, from the first line-up of Massive Attack, would be getting ready to go out, they would be playing everything from Parliament to T-Rex. My Uncle Ken who helped to bring me up is a white guy who got me into black music – he used to play Al Green, Sam Cooke. I've been blessed because no one can put my music in a box – it's not black, it's not white, it's not female, it's not male."

Mixed Race opens with another haunting evocation of his mother, "Every Day", sung as an oedipal duet with Riley. He wrote it in response to seeing a picture of himself recently with his mother for the first time "which," he says, "made my knees go completely".

Who gave him the picture?

"My uncle brought it. We were doing a show in Belfast, last year. I've never seen a picture of us together before and that shook me. Last week, I found her death certificate, so it's kind of like, I'm starting to find out about my family. I found out my mother was born in Cardiff, so I've started investigating over the last year."

As he explains some of his new understanding of his family tree, I sense the researchers on Who Do You Think You Are? might find their budget stretched. "My great-grandmother's father was Spanish and Jamaican and he came over to Cornwall," he says, "working on ships and then he met my great-great-grandmother, who was Cornish. And then my mum's dad is African-American and he was here in the second world war, a GI. And Quaye, her name, is an African name: his father was chief of a tribe in Ghana…"

This global heritage adds to Tricky's sense of rootlessness, as much as anything, and his keen understanding of chance encounter. His music is always open to accidental liaisons. The new album features not only Franky Riley – who responded to his ad for a singer in a paper – but also a hardcore Jamaican singer, Terry Lynn, he discovered on YouTube, a haunting solo track from an Algerian guitarist, Hakim, who had turned up at his studio, a saxophone intervention from a busker he heard in the Marais, a nice meditation on the price of fame, written with Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream, and a freaky musical box solo by a friend, Charles, who had just done 13 years in the Foreign Legion.

"I'll go in the studio with anybody… anybody can sing, it's just finding the right words." The final track, "Bristol to London", is a collaboration with his 24-year-old half-brother Marlon Thaws, a reflection on gangster life that is more raw than Tricky often allows. "Marlon's life's been a lot different to mine," he says. "He's always been on the street, always in and out of prison. I used to look after him when he was younger but then, by the time he was 15, I was gone. He got into selling drugs; the next older brother, he's worse; I tried to get them both into music but the other one is just dark. Marlon, even with the going to jail and getting into trouble, he carried on writing lyrics."

The collaboration helped to remind Tricky what he has sometimes forgotten over the last decade: that he is first and foremost a songwriter. "Once I get the first two words," he says, "it's easy. I've never had writer's block, because it's not me who's really controlling it. I feel like I'm an aerial or it's like meditation."

The perception, I say, is that he has always been writing and playing for his mother. Is he also playing against his father, against masculine identities?

"No. I never think of him. I've got nothing against my father, but he's like a little child."

Do they have a relationship now?

"I talk to him once, maybe, every 10 years."

Not really a relationship, then…

He laughs. "When I was a kid, I was from a white ghetto, but I used to go down to his area, a black ghetto. He would drive past and shout, 'Son!' I'd say, 'Hey, Dad' and he'd drive on, not pick me up. I remember going into a club with my mates and seeing my dad there with his boys, smoking a big spliff – very Jamaican, you know? He'd just say, 'What are you doing in here?' That was it."

In digging through his past, Tricky has discovered that one of the reasons his father was absent from his life was self-protection. "My Uncle Martin was doing seven years in Dartmoor when my mum died. I came across a letter he sent: 'I'm looking forward to coming out and seeing Roy [Tricky's dad]. He's got a lot to answer for.' My uncle was a notorious man, so my dad stayed away from me from fear of him and my other uncles, partly. If my Uncle Martin says, 'Stay away', you stay away. He was in prison at that time for cutting off someone's ear and cutting their throat."

Is his uncle still around?

"Yeah, yeah," he says. "He's mellowed out now, really chilled, he's lost one eye and he's done so much prison… Uncle Tony, he's still a bit of a lad. They all wanted to be boxers and it didn't happen but they knew how to fight. That's how they made their cash. It was basically, like, if you had a club in Salford, you had to pay certain people. If you didn't want to pay, you'd call my uncle and his partner and they'd come and help sort it out."

Tricky's deeply ambiguous relationship with the violent posturing of hip-hop is rooted in this history. On Mixed Race, he typically puts the most threatening lyrics – of "Murder Weapon" for example – in the lilting vocal of Riley, feminising it. Why write about violence at all?

"It's always been around me," he says. "My cousin got murdered in East Ham a few years ago; he got shot in his head. I've had one uncle murdered in Bristol. A friend of the family got shot in his head and they chopped off his arms, his legs. You know, I'm a musician but I still hear a lot. If I wanted to do a gangsta rap album, I've more right to do it than most people, but it's just not me, so a song like 'Murder Weapon', I've got friends singing it, because I don't want to get too close to it."

He keeps his own aggression at arm's length these days in the boxing gym. In the past, he has studied jujitsu and t'ai chi. Martial arts have been his education, he suggests("School was nothing for me"), but since then: "I've found myself really needing some wisdom."

When I ask if he feels any religious impulse, he scoffs violently; he puts religion in the same category as politics. "A con that changes nothing." What, I wonder, did he make of Samantha Cameron's claims that she used to hang out with him while she was a student in Bristol?

He laughs. "I can't ever remember meeting her, to be honest. She's right about the places I used to go but I can't remember her. I think it's just, 'I'm a rich girl but I know people from the street.' I don't like it. If she really wanted to use my name, why not actually talk to me about what I know? If they could use me to help set up youth clubs or something, you know, great, but to claim my name, I think it's weak."

In the past, he suggests, it might have made him angry; now he mostly finds it amusing.

"I'm trying to ease my brain," he says, from time to time. "I'm trying to become more comfortable in myself. I used to see a psychiatrist in New York but I got bored. It's obvious I got problems, you know: my mum committed suicide when I was a kid. I moved around from place to place. I've been thinking about seeing a therapist again."

The music, presumably, has always been his best way of dealing with it?

"Yeah, but in some ways it is all still inside your head. My music life is great. It's in the real world, that's where I have the problem, sometimes relating to people. I can be angry, you know, still really dark in my mind."

Is he worried that by losing the anger, his music will lose something?

"If you've had pain," he suggests, "it's all in your muscle memory. Stopping smoking weed, seeing a therapist, it's not going to change anything."

His desire to be a better man, he says, and you believe him, is rooted in his desire to be, in his own way, a better father. "If I was 42 and didn't have a child," he says, "I think I'd be feeling my age, but as it is, you start to see it's their turn."

The previous week, his daughter had gone to a festival and he'd half-wondered if he might go along with her. She told him: "No way!" When they meet, he says, with a proud grin, she tends to give him the wisdom of teenage girls. Which is to say she laughs at his hair and what he is wearing. Does she have an interest in his music?

"I think she has 6,000 songs on her iPod," he says. "Only one of them is mine, 'Hell Is Around the Corner'." If she was hoping to understand her father, it's a good choice: "Let me take you down the corridors of my life," Tricky whispers demonically, concluding with the knowledge that has always seemed to most trouble him: "You've got to live with yourself." Is he getting closer to the answer of how to do that?

He believes he is. He's happier as a performer for a start ("I always thought you went out and entertained people and got nothing back in return. But in the last year, I've realised that what the crowd gives you is so amazing, that sometimes I just stand onstage and cry"). He's planning a reunion with his estranged friends in Massive Attack. He still thinks he has the perfect album in him. And he can make a home anywhere there is "a hotel with a bookshop nearby".

Which bookshelves does he browse?

He says he either goes first to either the true crime section or mind, body and spirit. At the moment, as a result, he has a volume of his friend Freddie Foreman's gangster memoirs on the go, as well as Jack Kornfield's Buddhist bestseller, A Path With Heart. "As I'm getting older, I feel I should resolve a few problems," he says. He's not mellowing exactly; he moves forward in contradictions.

Mixed Race is released on Domino on 27 September