In 1978, the Cars seemed almost too good to be true. US rock radio and mainstream record-buyers had been almost implacably resistant to punk: none of the Ramones’ albums had cracked the US Top 40, nor had Blondie. Patti Smith’s ascension to the upper reaches of the Billboard Hot 100 had been achieved only by getting Bruce Springsteen to co-write a hit with her. Now, here was a band that felt like a product of the new wave – short, punchy tracks, distorted guitars, a hint of arty angularity, a mannered vocalist – but that wrote incredibly polished pop songs. They sounded enough like a straightforward hard rock band to appeal to the kind of music fans who had looked on aghast when the Sex Pistols fetched up in America. There was a vague suggestion of AOR, even prog rock about the keyboards.

In 37 minutes, the Cars’ eponymous debut album featured enough indelible songwriting that the band joked it should be called The Cars’ Greatest Hits. Their record company did the rest: hired the defiantly un-punk producer of Queen and Journey, Roy Thomas Baker, to add radio-friendly gloss; packaged it in a sleeve that featured a gorgeous, grinning model over the band’s preferred selection of arty black and white photos.

It sold so well, and for so long – spending two and a half years on the US chart – that the Cars became embroiled in an argument about holding back the release of their follow-up with their label, who worried the band would effectively be competing with themselves.

You might have been forgiven for imagining the Cars represented a calculated bid to bring new wave to the American masses, but the way they sounded was just an accurate representation of the inside of frontman Ric Ocasek’s head. By the time the Cars formed, he had been around the block: already in his mid-30s and a father of four, he’d spent the early 70s in a Crosby Stills and Nash-esque acoustic trio called Milkwood. He loved straightforward pop music, but he loved what he called “the left side of the music brain”, too: “My taste was to always go for that mix, even back in the 60s,” he said. “I loved the Velvet Underground and the Carpenters”.

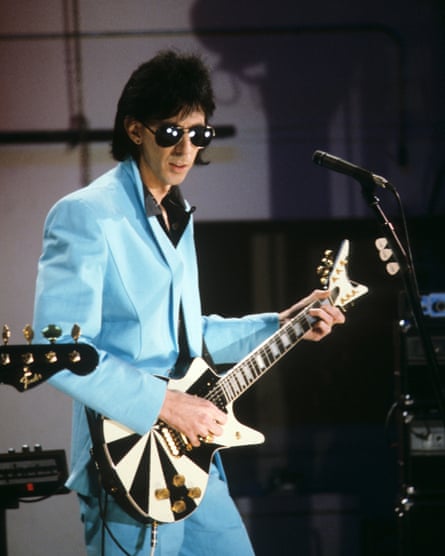

Old enough to remember 50s rock and roll first hand, he prized simplicity and directness in rock and knew the commercial value of a striking image – by all accounts a thoroughly charming man, he invariably hid behind a pair of sunglasses on-stage, projecting an air of aloof mysteriousness – but had an abiding passion for the experimental.

Left to his own devices, he made a solo album called Beatitude that sounded noticeably weirder than the Cars, bearing the audible influence of early Roxy Music and Berlin-era Bowie. When he branched out into production, he worked with hardcore punk band Bad Brains and Suicide. He gamely attempted to introduce the latter to the Cars’ audience, taking them on tour as a support act, with predictable results: “The booing started before they reached their second song,” Ocasek delightedly recalled.

The Cars represented a perfect synthesis of both sides of Ocasek’s taste. They could sound arty and left-field – particularly on their third, underrated album Panorama (1980) – but their success was driven by pure pop songwriting, at which he was astonishingly adept. For almost a decade, he gave the impression that knocking out huge hit singles came as second nature to him: Let’s Go, My Best Friend’s Girl, Shake It Up.

Furthermore, the Cars were pragmatic and adaptable. Some of their US rock peers were squeamish about developments such as the rise of synth-pop and of MTV, but the Cars had embraced synthesisers from the start and they seemed to welcome the importance of videos as another extension of the image-consciousness Ocasek and drummer Dave Robinson, who designed most of their sleeves, had displayed from the start.

Ocasek’s pop abilities reached a kind of pinnacle on 1984’s Heartbeat City, an exercise in mid-80s arena rock recorded with a master of that genre, producer Robert “Mutt” Lange, that was the most straightforwardly commercial album the Cars made, although Ocasek’s wiry vocals lent it at least a touch of oddness. Tellingly, he wrote but didn’t sing the album’s biggest hit, the super-smooth, ultra-radio-friendly ballad Drive. The album sold 4m copies in the US: six of its 10 tracks were released as singles.

Behind the scenes, however, there were problems, including mounting tensions between Ocasek and bassist Benjamin Orr, who sang lead vocals on a number of their hits, including Drive. Furthermore, Ocasek loathed touring, and it’s hard not to think that the sheer scale of Heartbeat City’s success may have influenced his decision to quit altogether. There was no longer any real financial imperative to keep doing it.

The Cars broke up after one more album, the lacklustre Door to Door (1987). When guitarist Elliot Easton and keyboard player Greg Hawkes mooted a reunion in the early 2000s, Ocasek demurred, and his former bandmates toured with Todd Rundgren as frontman, under the name the New Cars. Ocasek preferred to concentrate on a solo career, balancing sporadic releases that frequently leaned towards what he would have called the left side of the music brain (Getchertiktz, a collaboration with Suicide’s Alan Vega and writer Gillian McCain from 1996, featured spoken word and exploratory electronics) with production work.

By then, his production talents were frequently sought out by artists inspired by the Cars: Weezer, Guided By Voices, No Doubt. Just how influential the band’s early records were was underlined when the Strokes appeared. In case you had missed the fact that their sound was audibly indebted to the Cars, they covered their 1978 hit Just What I Needed live. And indeed, it became obvious when Ocasek was eventually inveigled into a Cars reunion in 2010, minus Orr, who died of cancer in 2000.

It wasn’t just that the handful of live shows Ocasek agreed to play were rapturously received, it was how contemporary their reunion album Move to This sounded. Not because they tried to sound contemporary, but because they didn’t need to. The way the Cars sounded in 1978 had become a sonic blueprint that permeated everything from alt-rock to mainstream pop.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion