What is the vestibuloocular reflex?

The vestibuloocular reflex or VOR is your “internal steadicam” or your “optical image stabilization”. The VOR is how our ears, eyes, and brain work together to keep our vision stable while we move. Read on to learn more about how your VOR works, what happens if a vestibular disorder causes it to malfunction, how we evaluate your VOR, and what treatments are effective for VOR loss.

What is the VOR?

The vestibuloocular reflex is what keeps your vision stable while your head is moving.

This is one of the fastest reflexes in your body, and is driven by activation of the vestibular system. The balance organs of your inner ear sense head movement. This sends a signal via the vestibular nerve to the brainstem, and causes activation of your eye muscles. This moves your eyes in the opposite direction of your head. A functioning VOR is what allows you to be able to read a sign clearly while walking. Your VOR is what allows you to keep looking at a stationary object while you turn your head.

Look at the letter X below. Keep your eyes on the X while you turn your head side to side. This is your VOR in action! Your vestibular system senses head movement and causes reflex activation of the muscles that move your eyes the opposite direction to head movement. This allows your eyes to stay steady and focused on the X while your head is turning.

X

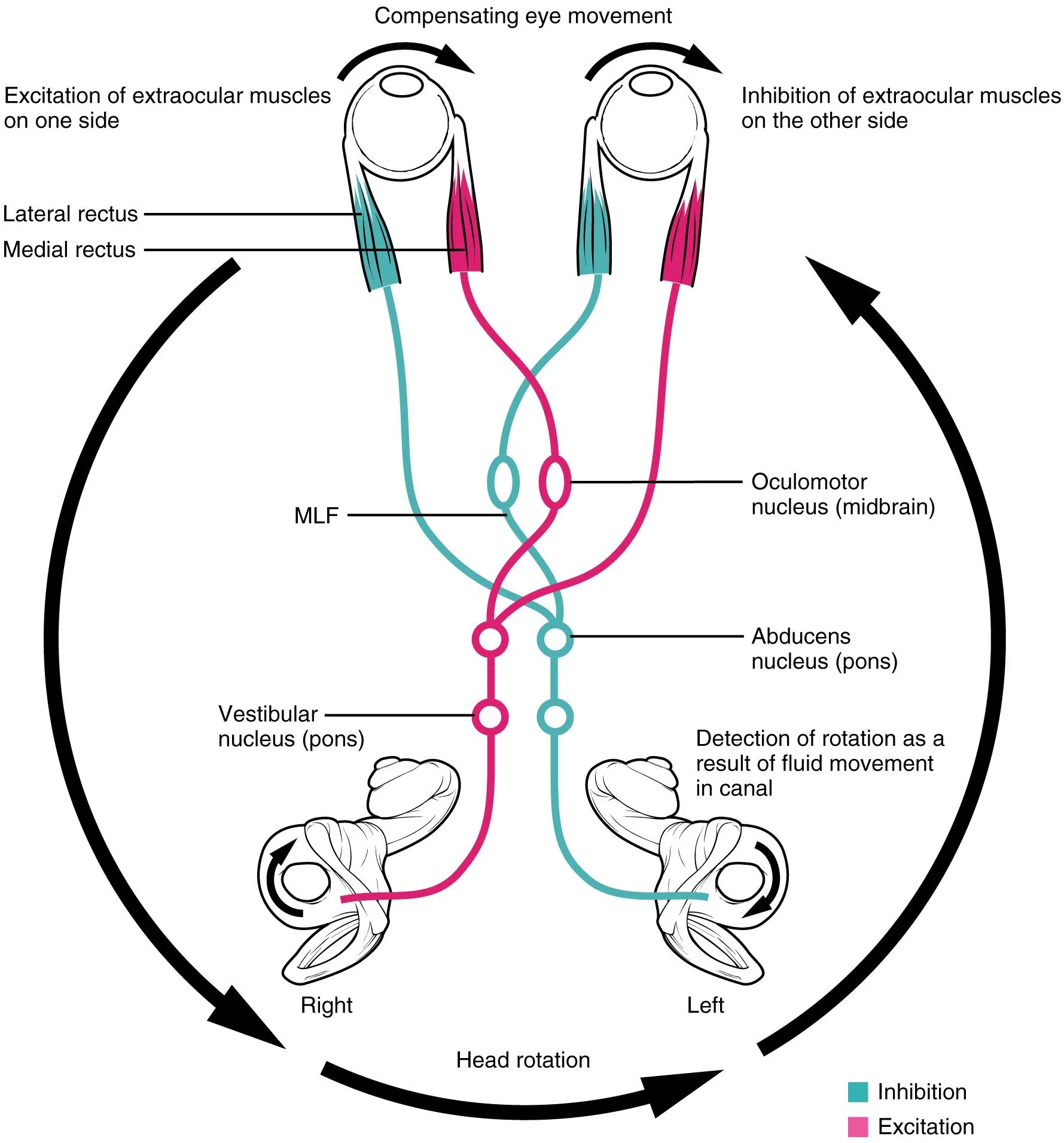

Here is a more detailed diagram of the vestibular pathway, showing how vestibular sensory signals are sent via the vestibulocochlear nerve to the vestibular nuclei in the brainstem, and the signals are then relayed onwards to trigger coordinated eye movements.

What happens if something goes wrong with the VOR?

Vestibular disorders can cause vision symptoms, because our inner ear and eyes need to work together via the VOR. If your VOR is not functioning properly, you may experience oscillopsia - which means blurring or bouncing vision with head movement, or a feeling that when your head moves your eyes lag behind. You may also experience dizziness or imbalance, particularly with head and body movements.

The VOR can be disrupted by loss of peripheral vestibular function - meaning a problem with the inner ear balance organs or the vestibular nerve. This can occur if the vestibular end organs are not able to sense head movement, or if the vestibular nerve is not able to send signals from the ear to the brain. This can affect one ear or both ears. The VOR can also malfunction because of problems in the central nervous system affecting vestibular pathways, particularly due to a problem in the brainstem or cerebellum.

How do we evaluate the VOR?

We can evaluate the function of your VOR by testing your ability to keep your eyes on a target while your head is moving. The two assessments we use during clinical evaluations are the head impulse test and dynamic visual acuity.

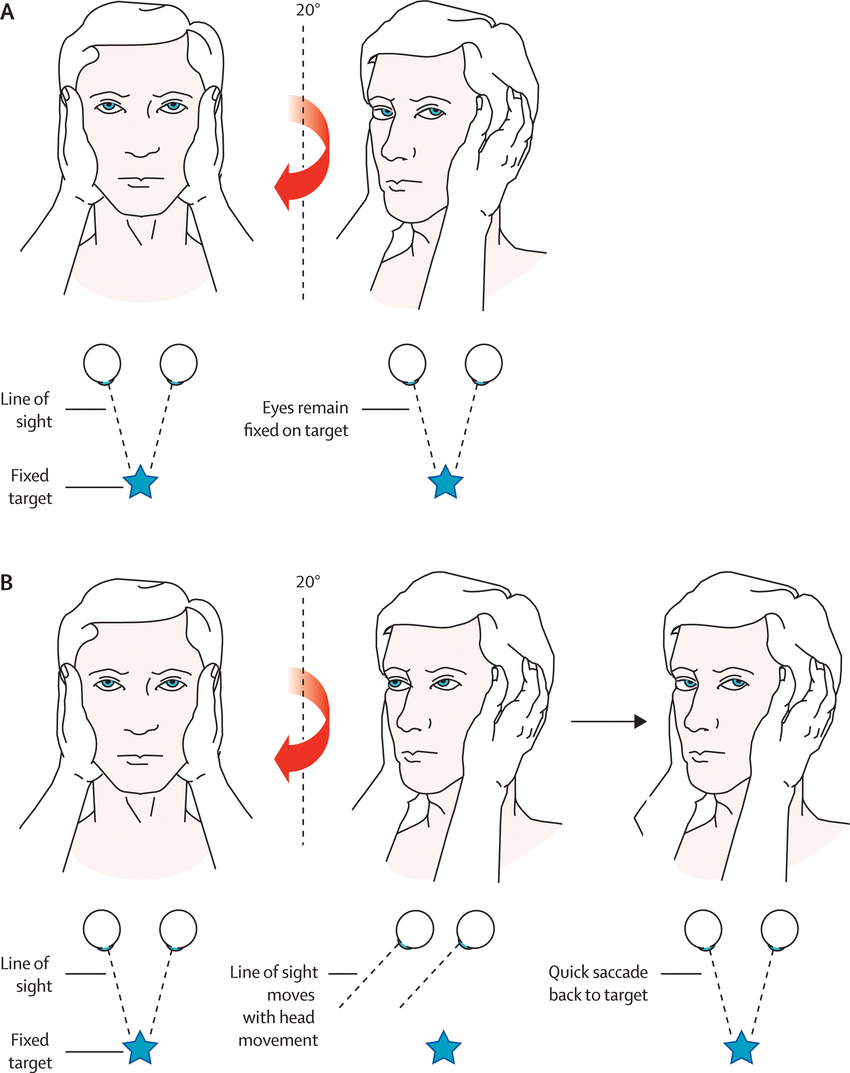

The head impulse test (also known as head thrust, Halmagyi maneuver, or Halmagyi-Curthoys test) tests your VOR. We ask you to keep looking at a target while we passively move your head a small amount. Moving your head in different directions allows us to test the function of each of the three semicircular canals in either ear. We watch your eyes closely to see if they stay steady on the target, or if your eyes first move with your head then make a small corrective movement (called a saccade) back to the target. If your eyes can’t stay fixed on the target, it is a sign that your VOR is not working properly.

(A) Normal and (B) abnormal head impulse test (figure from Nelson & Viirre 2009)

Dynamic visual acuity (DVA) tests your VOR by having you read an eye chart with your head still, and comparing this to what you are able to read while we move your head. The difference between what you can read with your head still versus moving tells us whether your VOR is functioning normally. DVA testing can help us to test and track improvements in your VOR function over as you participate in physiotherapy treatment.

Your VOR can also be evaluated during vestibular function testing with an audiologist with the video head impulse test (vHIT). This is like the clinical head impulse test, but using specialized goggles and a computer to track and record your eye and head movements.

Treatment for VOR problems

The purpose of vestibular rehabilitation exercises for VOR loss are to teach your brain to correct for the vestibular loss - this is referred to as central compensation. This happens through neuroplasticity, which describes your brain’s ability to change and adapt.

Gaze stability exercises (also known as VOR adaptation exercises) help train your brain to adjust the VOR, and generate corrective eye movements while your head is moving. These exercises involve keeping your eyes focused on a visual target while you move your head. It is important to do these exercises correctly to get maximum benefit - they do not retrain your brain as effectively if you do them at too fast or too slow a speed. While performing the exercise, you move your head as quickly as you can tolerate as long as you perceive the visual target to be stable and in focus. Neuroplastic change takes time and repetition, so these exercises are less effective if not done for long enough or frequently enough. The current clinical best practice guidelines recommend that these exercises should be performed 3 to 5 times per day for a total of 12 to 20 minutes per day, for at least 4 to 7 weeks. Using these guidelines, your vestibular physiotherapist will tailor your exercise program to your diagnosis, individual symptoms, and tolerance level.

A physiotherapist who specializes in vestibular rehabilitation can evaluate your VOR and determine what exercises are right for you.

Get in touch with one of our physiotherapists for more information!