You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Chris</strong> M. Dorn’eich<br />

張騫<br />

Zhang Qian<br />

THE SECRET MISSION<br />

OF HAN EMPEROR WU IN SEARCH OF THE RUZHI (YUEZHI)<br />

AND THE FALL OF THE GRÆCO-BACTRIAN KINGDOM<br />

(ANNOTATED COMPILATION OF EASTERN AND WESTERN SOURCES)<br />

Berlin 2008

<strong>Chris</strong> M. Dorn’eich<br />

張騫<br />

Zhang Qian<br />

THE SECRET MISSION<br />

OF HAN EMPEROR WU IN SEARCH OF THE RUZHI (YUEZHI)<br />

AND THE FALL OF THE GRÆCO-BACTRIAN KINGDOM<br />

(ANNOTATED COMPILATION OF EASTERN AND WESTERN SOURCES)<br />

Berlin 2008

CONTENTS<br />

Summary IV<br />

1 — In what year did Zhang Qian reach the Oxus River ? 1<br />

2 — Are we entitled to equate ›Daxia‹ with Tochara ? 29<br />

3 — How are we to understand the four names in Strabo’s list ? 73<br />

Bibliography 97<br />

Map 107<br />

— V —

S UMMARY<br />

The following study grew out of comments I started to jot down after Professor Falk had<br />

given me a new article by FRANTZ GRENET: ›Nouvelles données sur la localisation des cinq<br />

“ yabghus” des Yuezhi‹, Journal asiatique (Paris) 294/2–2006, published 2007. When the author<br />

was so kind as to send me an off-print a little later, I read it once again with even greater<br />

interest. My reaction was that for my own better understanding I wanted to clarify:<br />

— the chronology of Zhang Qian’s mission;<br />

— the meaning and extent of Chinese 大夏 (Da–xia);<br />

— the correct reading of Chinese 月氏 (“Ru–zhi” in place of the mistaken “Yue–zhi”).<br />

My comments kept growing over the next six or seven months and in time I found out<br />

that the last topic was a very complex one and called for a separate paper. In the end, it was<br />

superceded by a topic which evolved from the others: the number of nomadic nations that<br />

ended Greek rule in Bactria.<br />

(1) Chronology of Zhang Qian.<br />

As far as Zhang Qian’s famous mission was concerned, I found it strange that for the<br />

year of his arrival at the Ruzhi court, then on the north side of the Oxus River, I found so<br />

many different figures. This was odd because the one and only source on this is the oldest<br />

Chinese history book, the ›Shiji‹, mainly chapter 123, where Zhang Qian’s ›Report‹, at least in<br />

part, is reproduced. He tells us therein that the Ruzhi had conquered the Daxia who were,<br />

however, without a king. Many later authors understood this to mean that the Ruzhi had not<br />

really taken over the lands south of the Oxus.<br />

If Zhang Qian had arrived years after the advent of the Ruzhi, this view would be admissible.<br />

But the following study shows that Zhang Qian arrived on the scene within a few<br />

months of the Ruzhi takeover. From this it follows that the Daxia had become subjects of the<br />

Ruzhi who were now fully involved in establishing a new order. They pointedly showed<br />

Zhang Qian the flourishing markets in 藍市 Lanshi, the old capital of Daxia. It was only in<br />

the very beginning that the Ruzhi, coming from Sogdiana, had preferred to establish the<br />

(rather provisional) court of their king on the near side of the Oxus.<br />

(2) Meaning of 大夏 Daxia.<br />

The great problem of the otherwise excellent Chinese sources is the distortion of foreign<br />

names when transcribed into Chinese. This is so to the present day. What unsuspecting<br />

reader would guess that 美國, the State of “Mei,” is in fact (A)me(rica) ? Since high antiquity,<br />

the Chinese transcribed foreign names in cumbersome ways and then abbreviated these<br />

drastically — and not always to the first syllables of such a name.<br />

The present study shows that the very old (impossible) equation Daxia = Bactria has<br />

blocked the correct interpretation of the country, people and language named Daxia. Even<br />

CHAVANNES, undisputed authority in matters Chinese, fell into this trap, printing Ta-hia =<br />

Bactria. Later he did a fine translation of one chapter of the Tangshu and stated: “ Notice sur<br />

le T’ou-ho-lo (Tokharestan). Le T’ou-ho-lo ... c’est l’ancien territoire (du royaume) de Ta-hia.”<br />

Hence, Daxia was the ancient Tochara, the later Tocharistan. Tochara is not an equivalent<br />

of Bactria, it is only its eastern portion: this makes a decisive difference. The second<br />

chapter of the following study is based on the three crucial identifications:<br />

— 大夏 Daxia = Tochara (not Bactria);<br />

— 藍市 Lanshi = Darapsa (not Bactra);<br />

— 濮達 Puta = Bactra (not Pu•kalåvatð).<br />

All other assumptions are consequences of these three equations. They help us to understand<br />

that the Daxia of Zhang Qian are the Tochari of Trogus — which is not at all surprising<br />

as Trogus, too, states that the Asiani (Ruzhi) became the kings of the Tochari (Daxia).<br />

These identifications also help us to realize that the Ruzhi, ruling Daxia from Lanshi in the<br />

times of the Former Han (206 BCE – 25 CE), are still ruling from there at the beginning of the<br />

— V —

Later Han (26 CE), i.e. over a hundred and fifty years later. This means that the Ruzhi had<br />

been confined to Tochara for a long time — held in check by their immediate western<br />

neighbors, the awesome Parthians, suzerains of a vassal Saka state in Bactra. The Parthians<br />

even tried to drive the Ruzhi out of Tochara. Trogus, in the Epitome of Justin, tells us<br />

that Artabanus attacked the Tochari, in about 123 BCE. The Parthian king is killed in action<br />

and the situation remains undecided. About two generations later, in the first century BCE,<br />

the Ruzhi break through the Hindukush rampart and establish themselves in the Kabul<br />

Valley. A full century later still it is the founder of a new dynasty who unites all Ruzhi forces<br />

under his command. With this, he is finally in a position to attack the mighty Parthians and<br />

drive them out of three key positions: Kabul, Bactra and Taxila — in that order.<br />

(3) Strabo’s List of Four.<br />

Zhang Qian clearly describes the Daxia as the indigenous population of Eastern Bactria.<br />

With this, it can be shown that the Daxia, or Tocharians, have never been conquering nomads.<br />

With Zhang Qian we know that the Tochari had dwelled in the land of their name<br />

since at least a few centuries — and under a wide range of foreign invaders: Achaemenid<br />

Persians, Alexander the Great, Bactrian Greeks, Central Asian Sakas and then the Far<br />

Eastern Ruzhi, who all left their mark in the Tocharian language.<br />

It has often been repeated that Strabo lists four, but Trogus just two conquering nomad<br />

nations in connection with the fall of Greek Bactria — and that the Chinese sources know<br />

only one such nation, the Ruzhi. This study establishes the fact that the Chinese historians,<br />

too, speak of two conquering peoples. In the ›Hanshu‹ we are told what had been overlooked<br />

in all translations: the 塞王 Saiwang or “ Royal Sakas” had briefly ruled in Daxia/Tochara<br />

before they were evicted from this part of Bactria by the Ruzhi.<br />

With Trogus corroborated by the ›Shiji‹ and the ›Hanshu‹, Strabo’s vexed list becomes the<br />

main target for the concluding investigations. One name on that list has always been questioned.<br />

It will be shown now that, in fact, two names do not belong on that list: the Pasiani<br />

and the Tochari. Strabo left an unpublished manuscript when he died. It contained hundreds<br />

of marginal notes. With this we are safe to assume that Strabo had added the two names in<br />

question in the margins of his manuscript. The later unknown editor took it for granted that<br />

Strabo wanted to add these two names to his list — which so far included only the Asioi (Ruzhi)<br />

and the Sakaraukai (Saiwang). Strabo in Amaseia had used the very same source as<br />

before him Trogus in Rome: the ›Parthian History‹ of Apollodoros of Artemita.<br />

In the past, the fall of the Greek kingdom in Bactria has always been reconstructed in a<br />

way which remained in contradiction to this or that part of the historical evidence. Based on<br />

a step by step evaluation of both the Western and Eastern sources, quoted verbatim, this study<br />

outlines the complex sequence of historical happenings which lead to the destruction of<br />

Greek power north of the Hindukush.<br />

Thus, new insight is gained in a number of different topics. The more important are:<br />

— The genuine Tocharians have for centuries been firmly settled in Tochara/Tocharistan;<br />

— the conquering Ruzhi were confined to Tochara, or Eastern Bactria, for over 150 years, held<br />

in check by the more powerful Parthians;<br />

— in this long time the Ruzhi become known as the new (or pseudo-) Tocharians;<br />

— the balance of power, in favor of the Parthians so far, is only reversed by the mid-first century<br />

CE when a self-proclaimed Ruzhi king manages to evict the mighty Parthians from the<br />

Kohistan, Western Bactria, and the Panjab as well as the whole of the Indus Valley. With this,<br />

the foundations were laid for a new superpower in Central and South Asia: that of the Ruzhi<br />

under the Kushan dynasty. Ptolemy, in the later 2nd century CE, splashes the name Tochari<br />

(and variants) over all the places where the Ruzhi had been in the past three hundred years,<br />

culminating in his calling the last Far Eastern “ ordos” of the Ruzhi — close to Han China, the<br />

Zhaowu 昭武 of the Chinese sources (modern Zhangye 張掖 ) — Qog£ra (Thogara).<br />

— V —

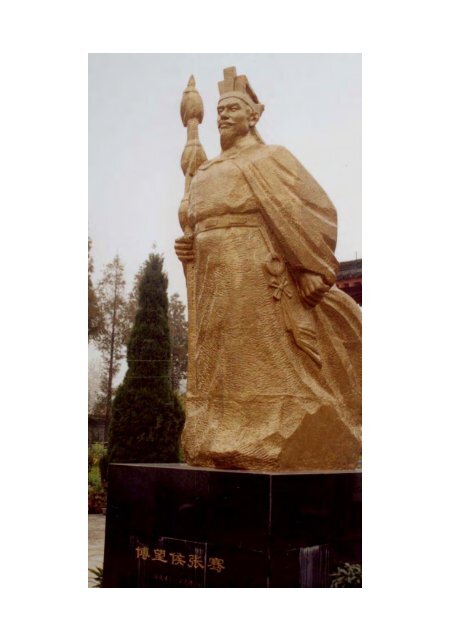

CHRIS M. DORN’EICH 2004<br />

“ The Bowang marquis, Zhang Qian”<br />

NEW STATUE IN FRONT OF THE ANCIENT GRAVE MOUND OUTSIDE CHENGGU (HANZHONG)<br />

— 1 —

張騫<br />

Zhang Qian<br />

THE SECRET MISSION<br />

OF HAN EMPEROR WU IN SEARCH OF THE RUZHI (YUEZHI)<br />

AND THE FALL OF THE GRÆCO-BACTRIAN KINGDOM<br />

(ANNOTATED COMPILATION OF EASTERN AND WESTERN SOURCES)<br />

1. IN WHAT YEAR DID ZHANG QIAN REACH THE OXUS RIVER ?<br />

Ever since the publication, in 1738, of GOTTLIEB SIEGFRIED BAYER’s Historia Regni<br />

Graecorum Bactriani, St. Petersburg, the Hellenistic kingdom in distant Bactria has<br />

intrigued students and scholars of Asian history. The exact time and circumstances of<br />

the foundation of this ancient kingdom, in about the middle of the third century BCE,<br />

have always been hotly debated. But the collapse of this highly developed culture — a<br />

vibrant blend of Greek, Persian, Indian and local influences — about a century later<br />

has proved even more difficult to elucidate, beyond the fact that it was due, as is well<br />

known and universally accepted, to an onslaught of an uncertain number of nomadic<br />

peoples, bursting forth from the wide steppes in the north-east of Central Asia.<br />

Regarding the violent end of the Græco-Bactrian kingdom, north of the Hindukush<br />

Mountains in present North Afghanistan, we have very short classical Western sources:<br />

the extant Prologi of Pompeius Trogus and a few statements in the Geography of Strabo.<br />

Of the 44 books of Trogus’ World History, published in the time of Augustus, books<br />

41 and 42 primarily contained the history of the Parthians. But they also included remarks<br />

on the history of the latter’s eastern neighbors, the Græco-Bactrians. Trogus’<br />

bulky work has been lost, however, only his just mentioned Prologi and a pitiful Epitome,<br />

done by a later hand and containing hardly more than one tenth of the original<br />

work, have come down to us. Also lost is the original source book for both Trogus and<br />

Strabo, namely the Parthian History by Apollodoros of Artemita. And lost, too, is Strabo’s<br />

other (and earlier) main work, his History, which may have contained a chapter<br />

on the history of the then eastern extremity of the Græco-Roman world.<br />

As far as our written sources are concerned, it is a fortunate fact that we have on<br />

the downfall of the Greeks in Bactria — for the first time in world history —, not only<br />

Western, but also Eastern sources to draw from. These are the Chinese Standard Histories<br />

正史, mainly the first two, the Shiji 史記 and the Hanshu 漢書. These two<br />

Chinese history books reproduce the precious report of our sole eyewitness on the<br />

scene, the Chinese emissary of Han Emperor Wu 漢武帝: Zhang Qian 張騫 (d. 114<br />

BCE) by name — a man of outstanding abilities. To his sharp senses we owe a good<br />

number of first-hand observations which, albeit in an abridged form only, have come<br />

down to us.<br />

The present paper endeavors to extract from the ancient Chinese sources what<br />

Zhang Qian has to tell us about Bactria — and compare it with the knowledge from<br />

our classical Western sources. In this connection it is curious to note that the actual<br />

year in which Zhang Qian arrived at the shores of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya)<br />

and in Bactria is still very much disputed among modern scholars.<br />

— 1 —

The Chinese sources, however, are unequivocal about this year. Various texts in the<br />

Shiji unmistakably state that Zhang Qian — the first<br />

Chinese envoy who traveled so far<br />

west — was sent out in a secret mission by Emperor Wu, and eventually returned to<br />

the Chinese capital Chang ’an 長安 in the spring<br />

of 126 BCE.<br />

It is narrated in the Shiji that this mission lasted<br />

13 years. And Zhang Qian spent:<br />

— “more than 10 years” 十 餘 歲 in captivity with<br />

the Xiongnu;<br />

— “more than 1 year” 留 歲 餘 with the Ruzhi (Yuezhi)<br />

月氏 in Daxia (i.e. in the eastern<br />

half of Bactria);<br />

— “more than 1 year” 歲 餘 a second time as captive of the Xiongnu.<br />

To this we have to add short periods of time for four journeys:<br />

— starting from Longxi 隴西, the border town, until being arrested by the<br />

Xiongnu;<br />

— escaping from the Xiongnu (near Shule, i.e. Kashgar) until reaching the 月氏;<br />

— returning<br />

from Daxia until being arrested by the Xiongnu again;<br />

— escaping from the ordos of the Xiongnu chanyu<br />

單于 until reaching Chang‘an.<br />

All four journeys together must have lasted less<br />

than 1 year. Of the first we can surmise<br />

that it lasted only days or weeks. The second one across the Pamirs and Sogdiana may<br />

have lasted some 3–4 months. The third one is not so easy to estimate, but cannot have<br />

been shorter than 3 months. The fourth should have been a matter<br />

of weeks as the distance<br />

was short and Zhang Qian this time escaped in the company<br />

of Yudan 於單, the<br />

deposed<br />

Xiongnu crown prince, and the two men were able to help each other effec-<br />

tively: Yudan in the Xiongnu Empire and Zhang Qian in Han China.<br />

With this information, it is clear that the historic mission started in the spring<br />

of 139 BCE — and not in 138, as even some Chinese and Japanese scholars believed<br />

or still believe. It is clear, therefore, that our Chinese Ulysses arrived at the ordos or<br />

court of the 月氏 in the company of just his Xiongnu servant Gan Fu 甘父 “after more<br />

than 10 years” as a captive of the Xiongnu and some three to four months traveling, i.e.<br />

in the summer of 129 — and not 128 as most modern texts erroneously tell us. This<br />

is a particularly important correction.<br />

Zhang Qian left Daxia in the fall of 128 and spent all of 127 with the Xiongnu again,<br />

and then escaped a second time in late winter or early spring of 126 BCE.<br />

In exile, the Xiongnu crown prince Yudan was made a “marquis” by Han Emperor<br />

Wu on May 2, 126 BCE, but soon afterwards he died.<br />

The third year ›yuan–shuo‹, fourth<br />

month, (day) ›bingzi‹, was (the start<br />

of) the first year of Yudan as marquis.<br />

In the fifth month he died.<br />

Shiji 20. 1031<br />

元 朔 三 年 四 月 丙 子 侯 于 單 元<br />

年<br />

五 月 卒<br />

It is surely of particular importance to know the exact time of arrival of Zhang Qian<br />

at his<br />

destination — the court of the Ruzhi (Yuezhi) 月氏, whom he found newly estab-<br />

lished on the north bank of the Oxus River, the modern Amu Darya.<br />

As for the Ruzhi 月氏, a short remark on their name is due here. The reading<br />

“Ruzhi” for Chinese 月氏, which I give in this article, is rather new and still widely unknown<br />

in the West. But as early as 1991: 92, the authoritative “Lexicon to the Shiji,” or<br />

Shiji Cidian 史 記 辭 典, decreed:<br />

月氏, pronounced Ròuzhð —【月氏 (ròu zhð 肉支)】...<br />

n for this is that 月氏 is in fact an ancient 肉氏, to be read accordingly.<br />

The reaso<br />

The<br />

magnificent catalogue to the exposition Ursprünge der Seidenstrasse (“The Origins<br />

of the Silk Road”), which I saw here in Berlin in December 2007 and which is<br />

based on originally Chinese texts, states on page 286:<br />

... die Yuezhi (nach anderer Lesart: Rouzhi) ...<br />

— 2 —

The modern reading of the Chinese character 肉 (meat) is “ròu,” but in ancient<br />

times the reading was “rù” — which I prefer as it is closer to our extant Western<br />

names of the 月氏, namely Rishi(ka), Asioi / Asiani, Arsi and ÅrÝi. For the same reason,<br />

I like to see in ›氏‹, read ›zhð‹ with Shiji commentator Zhang Shoujie 張守節 (8th c.),<br />

the closest-possible Chinese approximation to the sound of ›si‹, thus giving us Ru–si —<br />

so much closer to the above Western names than “Yue–si” can ever be.<br />

There is still more sound evidence for this identification. Whereas there are indications<br />

that the sound of ›月‹ was › i u ɐ t ‹ in Middle Chinese, this sound, with the<br />

help of Uighur-inherited pronunciations of Chinese characters, has been reconstructed<br />

recently as an older, or Tang-time, › u r / a r ‹ which was written ›wr‹ and ›’r‹ in Old Uighur<br />

script (Prof. SHÕGAITO 庄垣內 in a lecture in Berlin, March 2007). This, in all probability,<br />

suggests a perfectly fitting revised reading of 月氏 as Ar–si.<br />

As shown above, the historic date of Zhang Qian’s arrival at the Royal court of the<br />

Ruzhi 肉氏 (later spelled 月氏, and for a long time incorrectly transcribed “Yuè–zhð”<br />

in Pinyin) is: Summer of 129 BCE. In other words: Zhang Qian arrived in Daxia<br />

within a few months of the final fall of the Greek kingdom of Bactria — which, as<br />

can be deduced from numismatic and other evidence, still existed in the year 130 BCE.<br />

To know this, is indeed of importance to clearly understand the Shiji’s description of<br />

Daxia, located directly to the east of the final Greek possessions around the capital<br />

Bactra.<br />

It is interesting to note that the year of Zhang Qian’s arrival at the Oxus River was<br />

correctly calculated by DE GUIGNES in 1759 and by BERNARD in 1973. In the more than<br />

two hundred years between the two eminent French Orientalists we find an astonishing<br />

range of incorrect calculations. 1759: 24, DE GUIGNES writes:<br />

J’ai dit plus haut que Tcham-kiao rentra dans la Chine l’an 126 avant J.C. Il avoit employé<br />

treize ans à faire ce long voyage; il étoit donc parti vers l’an 139 avant J.C. Mais comme<br />

il étoit resté pendant dix ans prisonnier chez les Huns, il n’a pû arriver chez les Yue-chi<br />

que vers l’an 129 ...<br />

I stop quoting this early study here because the author goes on to say that Zhang<br />

Qian 張騫 (Tcham–kiao) stayed with the Ruzhi 月氏 until the year 127 — & peut-être<br />

une partie de 126. This, of course, is clearly impossible. 1973: 111, BERNARD writes:<br />

Il est incontestable qu’en 129 av. J.-C. — la date du voyage de Chang K’ien est fixée de<br />

façon sûre par les annales chinoises — la Bactriane avait perdu son indépendance politique<br />

au profit des Yué-chi, mais elle gardait encore l’identité d’un état vassal ...<br />

Here we see why it is so important to know the exact time of Zhang Qian’s arrival at<br />

the Ruzhi 月氏 court: it is the closest terminus ante quem for the final destruction of<br />

Greek Bactria we know of. Yet, almost nowhere in our modern Western literature — as<br />

far as I can ascertain — are we told that Zhang Qian arrived at the Oxus and the court<br />

of the 月氏 so early. This is all the more surprising as we have, today, as two thousand<br />

years ago, just one primary source to guide us: the Shiji, or magnum opus of<br />

Sima Tan (d. 110) and his son, Sima Qian (145–c.86). In 1825: 115-116, RÉMUSAT writes:<br />

L’empereur … choisit pour son ambassadeur Tchhang-kian, qui partit, accompagné de<br />

quelques autres officiers, pour aller trouver les Youeï-chi dans le lieu où ils s’étoient retirés<br />

… Tchhang-kian avoit à traverser, pour venir dans la Transoxane, des contrées qui<br />

étoient au pouvoir des Hioung-nou. Ceux-ci eurent connoissance de l’objet de son voyage,<br />

et réussirent à lui couper le chemin. Lui et ses compagnons furent arrêtés et retenus dix<br />

ans prisonniers …<br />

Ils parvinrent à s’échapper, et vinrent d’abord dans le Ta-wan … En voyant Tchhangkian,<br />

ils eurent beaucoup de joie … ils s’empressèrent de lui donner toute sorte de facilités<br />

pour aller dans la Sogdiane. Ce fut là qu’il apprit que les Youeï-chi … s’étoient rendus maîtres<br />

de Ta-hia. L’ambassadeur les suivit jusque dans ce dernier pays, au midi de l’Oxus;<br />

mais il ne put obtenir d’eux de quitter une contrée fertile, riche, abondante en toute sorte<br />

— 3 —

de productions, pour revenir dans les déserts de la Tartarie faire la guerre aux Hioung-nou.<br />

Tchang-kian, fort mécontent du mauvais succès de sa négociation, et ayant encore perdu<br />

une année chez les Youeï-chi … il prit sa route à travers les montagnes du Tibet: mais cela<br />

ne lui servit de rien; les Hioung-nou, dont les courses s’étendoient jusque là, le prirent encore<br />

une fois, et le retinrent assez long-temps. Il parvint enfin à s’échapper, à la faveur des<br />

troubles qui suivirent la mort du Tchhen-iu régnant, et revint en Chine après treize ans<br />

d’absence,<br />

accompagné d’un seul de ses collègues, le reste de l’ambassade.<br />

Leaving aside a few minor flaws in this rendering of the story as told in Shiji 123,<br />

RÉMUSAT does not give his readers any idea about the absolute chronology of Zhang<br />

Qian’s historic mission. To do so, he would have had to state the name of the Xiongnu<br />

chanyu 單于 (emperor) who had died when Zhang Qian finally escaped in the company<br />

of that<br />

chanyu’s son and crown prince. To find out, RÉMUSAT would have had to<br />

read<br />

Shiji 110. We do not know whether he did. From this early translation, it is impossible<br />

to know in what year Zhang Qian arrived at the Oxus River.<br />

One year later, 1826: 57, KLAPROTH told the story this way:<br />

La nation de Yue tchi habitait alors entre l’extrémité occidentale de la province de Chen<br />

si, les Montagnes célestes et le Kuen lun, c’est-à-dire dans le pays que nous appelons à<br />

présent le Tangout, où elle avait formé un royaume puissant. En 165, les Hioung nous l’attaquèrent,<br />

la chassèrent à l’occident, ou elle se fixa en Transoxiane.<br />

L’empereur Wou ti rechercha l’alliance des Yue tchi, parcequ’il espérait qu’ils se réuniraient<br />

avec lui contre les Hioung nou. Le Tchhen yu ayant pénétré ce dessein chercha tous<br />

les moyens pour le faire échouer.<br />

Tchang khian s’était offert à l’empereur pour entreprendre le voyage en Transoxiane, et<br />

il avait demandé à être accompagné d’environ cent hommes; mais, en passant par le pays<br />

des<br />

Hioung nou, il fut arrêté avec sa suite et retenu prisonnier pendant dix ans; au bout de<br />

ce temps il trouva l’occasion de s’évader, et marcha du côté de l’ouest. Il trouva les Yue tchi<br />

dans leur nouveau pays. L’envoyé chinois y séjourna pendant plus d’un an, au bout duquel,<br />

repassant chez les Hioung<br />

nou, il fut fait de nouveau prisonnier; mais il s’échappa, et revint<br />

en Chine après treize ans d’absence.<br />

In the margin of his text, next to the line Tchang khian s’était…, KLAPROTH gives<br />

“126 av. J.-C.” This way it is left to the imagination of the reader whether this absolute<br />

year<br />

applies to the departure from Chang’an, the arrival at the Oxus, or the return to<br />

China<br />

of Zhang Qian. A few pages later KLAPROTH adds:<br />

Le voyage que le général chinois Tchang khian entreprit, en 126 avant notre ère, dans<br />

les pays occidentaux, avait pour but de susciter des ennemis aux Hioung nou.<br />

From this sentence, readers were led to believe that the year stated was that of the<br />

departure of Zhang Qian. We may note here that we have to combine the texts of the<br />

two translators to get close to what is actually said in Shiji 123. And it is interesting to<br />

see that from now on Zhang Qian will always be a general in this story — as if he had<br />

been undertaking a military mission. In reality, this secret mission was purely<br />

political. Zhang Qian was only made a general a few years after his return to China as<br />

a reward<br />

for his merits as an ambassador.<br />

In 1836: 37-38, RÉMUSAT writes in a foot note to his splendid translation, published<br />

posthumously,<br />

of the Foguoji 佛國記, or “Memoirs of the Buddhist Kingdoms,” by the<br />

Chinese<br />

Buddhist monk and pilgrim to India in the years 399–414, Fa Xian 法顯,<br />

edited<br />

by KLAPROTH, who also died before the final publication:<br />

Tchang khian, que<br />

DEGUIGNES, par erreur, a nommé Tchang kiao, est un général chinois<br />

qui,<br />

sous le règne de Wou ti de la dynastie des Han, l’an 122 avant J. C., fit la première expédition<br />

mémorable dans l’Asie centrale. On l’avait envoyé en ambassade chez les Yue ti,<br />

mais il avait été retenu par les Hioung nou, et gardé dix ans chez ces peuples. Il s’y était<br />

même marié et avait eu des enfants. Durant ce séjour, il avait acquis une connaissance<br />

étendue des contrées situées à l’occident de la Chine. Il finit par s’échapper et s’enfuit à<br />

— 4 —

plusieurs dizaines de journées du côté de l’ouest, jusque dans le Ta wan (Farghana). De là<br />

il passa dans le Khang kiu (la Sogdiane), le pays des Yue ti et celui des Dahæ [Daxia].<br />

Pour éviter à son retour les obstacles qui l’avaient arrêté, il voulut passer au milieu des<br />

montagnes, par le pays des Khiang (le Tibet), mais il ne put éviter d’être encore pris par<br />

les Hioung nou … Il parvint à s’échapper de nouveau et revint en Chine après treize ans,<br />

n’ayant plus que deux compagnons, sur cent qui avaient formé sa suite à son départ. Les<br />

contrées qu’il avait visitées en personne étaient le Ta wan, le pays des grands Yue ti, celui<br />

des<br />

Ta hia (Dahæ) et le Khang kiu ou la Sogdiane.<br />

Comparing these texts with the Chinese original one realizes that the translators<br />

mixed their own comments into their renditions. What, then, did the Chinese text of<br />

Shiji 123 really say?<br />

To be sure, as early as 1828 one of the students of RÉMUSAT published a full and pioneering<br />

translation of this important chapter of the Shiji. He had done it under the<br />

close guidance of his teacher RÉMUSA T.<br />

His name was given as Brosset<br />

jeune (“Brosset<br />

jun ior”) — he was Monsieur Marie-Félicité Brosset who soon abandoned his sinological<br />

studies in favor of other Oriental languages. One reason may have been that his<br />

struggles<br />

with the Chinese language went largely unnoticed by the scholarly community<br />

o f Western Europe. Unfortunately, young Brosset’s French translation was reproduced<br />

without the original text. I include it here for the sake of easy comparison.<br />

( BROSSET 1828: 418–421)<br />

Les<br />

traces des Ta ouan (Fergana) sont con-<br />

nues<br />

depuis Tchang–kien,<br />

capitaine<br />

des Han, en l’année ›kien–youen‹<br />

( 140 ans avant J.-C.).<br />

A cette époque, le fils du Ciel interrogeant<br />

des<br />

Hiong–nou qui s’étaient soumis, apprit<br />

que<br />

les Hiong–nou avaient battu les Youe–<br />

chi,<br />

et fait une coupe du crâne de leur roi;<br />

qu’enfin les Youe–chi s’étaient dispersés, la<br />

rage dans le cœur contre les Hiong–nou,<br />

sans vouloir faire la paix avec eux.<br />

A ce récit, l’empereur des Han, qui souhaitait<br />

détruire les barbares des environs, et<br />

pour<br />

réaliser ses projets de communica-<br />

t<br />

le pays des Hiong–nou, fit chercher des<br />

gens capables de cette commission.<br />

Kien, capitaine de la caravane des Youe–<br />

chi, et Tchang–y–chi kou–hou nou–kan–fou<br />

sortirent ensemble par Long–si, se portant<br />

vers les Hiong–nou;<br />

ceux-ci les arrêtèrent et les livrèrent au<br />

Tchen–yu (c’était alors Lao–chang).<br />

Le Tchen–yu les retint …<br />

Il les garda dix ans et leur donna des femmes.<br />

Mais Tchang kien, qui avait ses instructions<br />

des Han et ne les perdait pas de vue;<br />

se<br />

trouvant tous les jours plus libre au mi-<br />

lieu<br />

des Hiong–nou, s’échappa avec ses<br />

compagnons,<br />

se dirigeant vers les Youe–chi<br />

( ils émigrèrent vers la grande Bucharie, en<br />

l’an<br />

139 avant Jésus-<strong>Chris</strong>t);<br />

Shiji 123. 3157–3159<br />

大 宛 之 跡 見 自 張 騫<br />

張 騫 漢 中 人<br />

建 元 中 為 郎<br />

是 時 天 子 問 匈 奴 降 者 皆<br />

言 匈 奴 破 月 氏 王 以 其 頭<br />

為 飲 器<br />

月 氏 遁 逃 而 常 怨 仇 匈 奴<br />

無 與 共 擊 之<br />

ions par des caravanes qui traverseraient 漢 方 欲 事 滅 胡 聞 此 言 因<br />

欲 通 使 道 必 更 匈 奴 中 乃<br />

募 能 使 者<br />

騫 以 郎 應 募 使 月 氏 與 堂<br />

邑 氏 ( 故 ) 胡 奴 甘 父 俱<br />

出 隴 西<br />

經 匈 奴 匈 奴 得 之 傳 詣 單<br />

于 單 于 留 之 …<br />

留 騫 十 餘 歲 與 妻 有 子 然<br />

騫 持 漢 節 不 失<br />

居 匈 奴 中 益 寬 騫 因 與 其<br />

— 5 —

et<br />

après quelques dixaines de jours de mar-<br />

che,<br />

il arriva à Ta ouan.<br />

Les gens du pays avaient entendu parler<br />

de<br />

la fertilité et des richesses des Han;<br />

mais,<br />

malgré tous leurs désirs, ils n’avaient<br />

pu nouer de communications. Ils virent<br />

Kien<br />

avec plaisir …<br />

Sur<br />

sa parole, le roi de Ta ouan lui donna<br />

des guides et des chevaux de poste, qui le<br />

menèrent à Kang–kiu (Samarkande). De là<br />

il fut remis à Ta–youe–chi.<br />

Le roi des Youe–chi avait été tué par les<br />

Hiong–nou, et son fils était sur le trône.<br />

Vainqueurs des Ta–hia (habitans du Candahar)<br />

les Youe–chi s’étaient fixés dans<br />

leur pays, gras et fertile, peu infesté de voleurs,<br />

et dont la population était paisible.<br />

En outre, depuis leur éloignement des Han,<br />

ils ne voulaient absolument plus obéir aux<br />

barbares.<br />

Kien pénétra, à travers les Youe–chi,<br />

à Ta–<br />

hia, et ne put obtenir des Youe–chi une lettre<br />

de soumission.<br />

Après un an de délai, revenant au mont<br />

Ping–nan, il voulut traverser le pays de<br />

Kiang; mais il fut repris par les Hiong–nou.<br />

Au bout d’un an, le Tchen–yu mourut. Le<br />

Ko–li–vang de la gauche battit l’héritier de<br />

la couronne, et se mit en sa place; l’intérieur<br />

du pays était en combustion.<br />

Kien, conjointement avec Hou–tsi et<br />

Tchang–y–fou, s’échappa et revint chez les<br />

Han (en l’année 127 avant J.-C.) ...<br />

屬 亡 鄉 月 氏 西 走 數 十 日<br />

至 大 宛<br />

大 宛 聞 漢 之 饒 財 欲 通 不<br />

得 見 騫 喜 …<br />

大 宛 以 為 然 遣 騫 為 發 導<br />

繹 抵 康 居 康 居 傳 致 大 月<br />

氏<br />

大 月 氏 王 已 為 胡 所 殺 立<br />

其 太 子 為 王<br />

既 臣 大 夏 而 居 地 肥 饒 少<br />

寇 志 安 樂 又 自 以 遠 漢 殊<br />

無 報 胡 之 心<br />

騫 從 月 氏 至 大 夏 竟 不 能<br />

得 月 氏 要 領<br />

留 歲 餘 還 並 南 山 欲 從 羌<br />

中 歸 復 為 匈 奴 所 得<br />

留 歲 餘 單 于 死 左 谷 蠡 王<br />

攻 其 太 子 自 立 國 內 亂<br />

騫 與 胡 妻 及 堂 邑 父 俱 亡<br />

歸 漢 …<br />

This then is what the two reputed Sinologists<br />

and one of their most ambitious stu-<br />

dents translate for those many Western Orientalists,<br />

Historians, Geographers etc.<br />

who — in this and over the next few generations<br />

— are unable to read Chinese them-<br />

selves. What do the latter make out of the translations and narratives<br />

?<br />

RITTER, 2 1837: 545; 547, writes:<br />

Einfluß des chinesischen Reiches auf West-Asien<br />

unter der Dynastie der Han (163 vor bis<br />

196 nach Chr. Geburt).<br />

Tschangkians Entdeckung<br />

von Ferghana, Sogdiana, Bactrien und<br />

der Handelsstraße nach Indien, um das J. 122<br />

vor Chr.G. … Hier ist der Ort, unter diesem<br />

Kaiser seines chinesischen Generals,<br />

Tschangkian, dessen wir schon früher einmal gedachten<br />

(Asien I, S. 201, 195),<br />

genauer zu erwähnen, als des Entdeckers<br />

Sogdianas, des Cas-<br />

pischen Meeres und Indiens, nicht als Eroberer,<br />

sondern als politischer Missionar, um das<br />

Jahr 122<br />

vor Chr. Geb. …<br />

It is not altogether clear, but one may guess that RITTER took the year<br />

122 BCE as<br />

the time of discovery, i.e. the year of Zhang Qian’s<br />

arrival in the Far West.<br />

LASSEN in 1838: 250 writes:<br />

In diesen Szu hat man längst die Saker er kannt und es stimmt damit,<br />

dass die Saker<br />

sich schon vor dem Falle des Baktrischen Reiches<br />

eines Theils Sogdianas bemächtigt hatten<br />

… Die Yuetchi stossen die<br />

Szu weiter und nehmen die von ihnen besetzten Gebiete ein;<br />

— 6 —

die Szu nach Süden gedrängt finden Gelegenheit,<br />

sich des Landes Kipin zu bemächtigen,<br />

die nachrückenden Yuetschi<br />

nehmen das Land<br />

der Tahia. Ein Chinesischer General<br />

Tchamkiao war auf diesem Zuge bei den Yuetschi<br />

und das wohlbegründete<br />

Ereignis fällt<br />

in die Zeit unmittelbar vor 126 vor Chr. Geburt.<br />

In 1829 and in St. Petersburg, the first gr<br />

eat Russian Sinologist BICHURIN published<br />

a translation of Hanshu 96, which does not<br />

contain Zhang Qian’ s biography nor his<br />

mission to the 月氏 — these went into Hanshu<br />

61 —, but it does mention Zhang Qian’s<br />

name a few times and includes an updated<br />

description of the people of the 月氏 and<br />

its early history. This translation into a We<br />

stern language went almost unnoticed by<br />

Western scholars. An exception is SCHOTT w ho published a book review of it, here in<br />

Berlin. In 1841: 164-165; 169, SCHOTT states:<br />

… gab der Pater Jakinph (Hyacinth) Bitschurinskij,<br />

früher eine Zeitlang Archimandrit<br />

an dem Griechischen Kloster in Peking … bereits<br />

vor zwölf Jahren vorliegendes Werk her-<br />

aus … aber seine Arbeit ist gleichwohl sehr verdienstlich, besonders … da der Verfasser<br />

hier aus einer Quelle geschöpft hat, die bis jetzt keinem Europäischen Sinologen zugäng-<br />

lich gewesen … Diese Beschreibung, im Originale<br />

Si-yü-tschuan (Kunde von den Si-yü,<br />

westliche Grenz-Regionen) betitelt, bildet einen<br />

integrierenden Theil der Annalen jenes<br />

Kaiserhauses, welches die Pariser Bibliothek schwerlich<br />

besitzen dürfte; denn Abel-Remu-<br />

sat hat seine<br />

Beiträge zur alten Geschichte Mittelasiens nur aus den Resumé’s entlehnt,<br />

die sich in Ma-tuan-lin’s kritischer Encyklopäd<br />

ie vorfinden … In seiner 18 Seiten starken<br />

Vorrede macht Pater Hyacinth folgende Bemerkung[en]<br />

:<br />

… Aber zwei Jahrhunderte<br />

vor u. Z. stiftete ein nördliches Barbarenvolk,<br />

von den Chinesen<br />

Hiong-nu genannt, eine ungeheure Steppen-Monarchie<br />

in Central- Asien, die das Reich<br />

der “Himmelssöhne” in langwierigen Kämpfen<br />

demüthigte, und der Chinesische Hof muss-<br />

te endlich auf ausserordentliche Maassregeln<br />

denken, um diesen gefährlichen Feind un-<br />

schädlich zu machen. Gefangene Hiong-nu sagten aus, auf der Landstrecke von der<br />

Grossen Mauer bis Chamul (Ha–mi) habe vor<br />

nicht gar langer Zeit ein mächtiges Volk —<br />

die Yue-tschi oder Yue-ti (Geten) — gewohnt,<br />

das<br />

aber, von den Hiong-nu verdrängt, ins fer-<br />

ne Abendland ausgewandert sei.<br />

Da schickte Kaiser Wu-ti (140 bis 85 vor Chr.),<br />

in der Hoffnung dieses Volk gegen die<br />

Hiong-nu aufzureizen, seinen General Tschang-kian<br />

als Bevollmächtigten an sie ab. Die<br />

Hiong-nu lauerten diesem Magnaten auf, und hielten ihn zehn Jahre lang in gefänglichem<br />

Gewahrsam, bis er endlich Gelegenheit fand zu entfliehen, und nun durch Fergana und<br />

Sogdiana zu den Yue-ti gelangte. Allein der Fürst dieser Nation, welcher die Ta-hia (Dacier)<br />

unterworfen<br />

und in ihrem Lande sich niedergelassen hatte, dachte in seinen schönen Besitzungen<br />

nicht mehr daran, sich an den Hiong-nu zu rächen. Tschang-kian verweilte hier<br />

einige Jahre, kehrte dann unverrichteter Sache zurück und fiel ein zweites Mal den Hiongnu<br />

in die Hände, aber Unruhen im Hiong-nu-Reiche verschafften ihm Gelegenheit,<br />

ein<br />

zweites Mal zu entrinnen; und so erreichte<br />

er (126 v.Ch.) endlich wieder seine Heimat …<br />

For the year of Zhang Qian’s return, BICHURIN’S calculation, 126 BCE, was the best<br />

so<br />

far. I have Bichurin’s Russian translation here before me, but regrettably not his<br />

preface.<br />

Hence I am unable to say, whether or not he had also calculated a definite year<br />

f or the arrival of the “general” at the court of the “Geten” (the Massagètes of RÉMUSAT<br />

1829:<br />

220). Anyway, beyond KLAPROTH and SCHOTT, few scholars in the West read BI-<br />

CHURIN’S<br />

translation of Hanshu 96. Among those who did not read it is the famous<br />

French geographer, VIVIEN DE SAINT-MARTIN. In 1850: 261–262, 267 (foot notes); 265, 292–<br />

293 (main text), he writes:<br />

Cet officier se nommait Tchang-Khian. Parti de la cour impériale en l’année 126,<br />

il fut arrêté<br />

en chemin par les Hioung-nou, qui pénétrèrent l’objet de sa mission, et qui le retinrent<br />

parmi<br />

eux. Tchang-Khian, parvenu enfin à s’évader après dix années de captivité, ne put<br />

conséquemment arriver chez les Yué-tchi qu’en l’année 116, et en effet il les trouva bien établis<br />

dans la Transoxane, qu’ils possédaient depuis dix ans …<br />

— 7 —

Mais ce qu’il nous est surtout important de connaître plus en détail, c’est la nation même<br />

des Yué-tchi … Le Pline chinois, Ma-touan-lin, a réuni au XIII e siècle ces anciennes notions,<br />

encore augmentées de notions plus récentes, et en a formé un article spécial parmi<br />

ceux qu’il consacre aux nations de l’intérieur de l’Asie. Nous insérons ici la traduction de ce<br />

morceau,<br />

qu’a bien voulu nous fournir M. Stanislas Julien; elle complète et rectifie en<br />

beaucoup de passages essentiels celle qu’Abel Rémusat en a donnée …<br />

Abel Rémusat et Klaproth identifient constamment le Ta-hia des relations chinoises<br />

avec la Bactriane, c’est-à-dire avec la partie orientale du Khoraçân actuel. Ce rapprochement<br />

ne nous paraît pas exact. Nous ne voyons nulle raison de nous éloigner ici de la synonymie<br />

naturelle que nous fournit la situation des Dahæ dans l’ancienne géographie classique,<br />

sur la côte S.-E. de la mer Caspienne, au midi de l’ancienne embouchure de<br />

l’Oxus …<br />

Ce que nous voyons quant à présent avec certitude, c’est … qu’après avoir séjourné pendant<br />

trente ans environ dans les pâturages de la Dzoûngarie, les Yué-tchi furent contraints<br />

par un nouveau refoulement de pousser plus loin leur émigration; qu’ils descendirent alors,<br />

vers les années 130 à 126 avant notre ère, dans les steppes du nord du Jaxartès, et que<br />

bientôt après, franchissant ce grand fleuve, ils vinrent s’emparer, en l’année 126, des riches<br />

provinces qui avaient appartenu peu avant aux rois grecs de la Bactriane, entre le Jaxartès<br />

et l’Oxus; qu’ils y établirent dès lors leur domination exclusive …<br />

It was a disaster of sorts that the Western translations of the “Chinese sources”<br />

should start with the late “Encyclopedia” 文獻通考 of MA D UANLIN 馬端臨 instead of<br />

w ith the Chinese Standard Histories 正史, which MA DUANLIN had reworked in a very<br />

superficial,<br />

confused, or at least confusing, manner. It took a long time to repair the<br />

damage.<br />

Later authors strongly warned against using MA DUANLIN indiscriminately.<br />

Once again I must quote LASSEN who, in 2 1874: 370-371, writes:<br />

Die Zeit dieses Ereignisses lässt sich mit ziemlicher Genauigkeit nach den Berichten<br />

über die Sendung des Chinesischen Generals Tchangkian zu den Jueïtchi feststellen. Der<br />

Kaiser Wuti aus der Familie der Han, welcher von 140—80 vor Chr. G. regierte, in der Absicht,<br />

die Hiungnu zu nöthigen, ihre<br />

Waffen gegen Westen zu richten und dadurch sein<br />

Reich<br />

von ihren fortwährenden räuberischen Einfällen zu befreien, beschloss, ein Bündnis<br />

mit ihren Feinden, den Jueïtchi, zu schliessen und sie zu einem Kriege gegen sie zu bewegen;<br />

er beauftragte den oben genannten General mit der Unterhandlung. Als dieser die<br />

Jueïtchi erreichte, fand er sie schon im Besitze von Tahia und nicht geneigt, sich an den<br />

Hiungnu zu rächen … Da sie ausserdem zu entfernt von den Chinesen wohnten, konnten<br />

sie sich nicht entschliessen, dem Tchangkian den Oberbefehl über ein Heer zu geben und<br />

in die raue und wüste Gegend ihrer früheren Wohnsitze zurückzukehren. Der Gesandte<br />

des Chinesischen Kaisers kehrte daher unverrichteter Sache in sein Vaterland zurück.<br />

Das Jahr seiner Rückkehr wird nicht übereinstimmend angegeben. Nach einer Angabe<br />

kehrte er im Jahre 126 vor Chr. G. zurück, nach einer andern 122. Der älteste Chinesische<br />

Geschichtsschreiber,<br />

bei welchem eine Bestimmung hierüber sich findet, Ssémathsien,<br />

lässt die Abreise zwischen den Jahren 140 und 134 vor Chr. G. stattfinden (in seinem Sséki,<br />

§ 123). Es bleibt daher zweifelhaft, ob die zwei Jahre, welche er bei den Jueïtchi zubrachte,<br />

von 130 oder 124 an zu zählen sind ... Da die Angabe, dass Tchangkian im Jahre 122 zurückkehrte,<br />

sich in einem aus Chinesischen Quellen geschöpften Werke findet, möchte sie<br />

als die richte betrachtet werden.<br />

LASSEN shows great respect for RÉMUSAT’s translation of the first of the famous<br />

Chinese Buddhist pilgrims who came<br />

to the holy land of India and wrote detailed repor<br />

ts: primary sources of the highest importance. In 1874 LASSEN copies RÉMUSAT’s<br />

mistake<br />

of 1836. But he also remarks that the year 122 is in clear contradiction to an-<br />

other<br />

of RÉMUSAT’s notes, namely that Zhang Qian, after his return, was made a mili-<br />

t ary commander in 123 BCE. LASSEN had not been told that Shiji 123 states in simple,<br />

u nmistakable terms Zhang Qian’s year of return (at least as far as the authors were<br />

concerned — how should they know that later readers would no longer<br />

be familiar<br />

— 8 —

with<br />

the Chinese calendar ?). LASSEN was caught between doubt and praise. One solu-<br />

t ion to his dilemma could be that the figure 122, in fact, was a printer’s mistake for<br />

127<br />

— the year of return that “BROSSET jeune” published in 1828, worked out with his<br />

t eacher RÉMUSAT. With all its shortcomings BROSSET’s early translation remained the<br />

main<br />

entry point to the Chinese sources for the next author.<br />

In 1877: 448–452, VON RICHTHOFEN writes:<br />

Entdeckung der Länder am Oxus und Yaxartes durch Tshang-kiën (~128 v.Chr.). Als<br />

Hsia[o]-wu-ti (140 bis 86), der glücklichste der Han-Kaiser, zur Regierung kam, begannen<br />

die Hiungnu, die sich seit 160 ruhig verhalten hatten, abermals Einfälle in das Reich. Ein<br />

einsichtsvoller und kräftiger Regent, beschloss er, ihre Macht zu brechen und die Carawanenwege<br />

durch das von ihnen beherrschte Land für sich zu öffnen. Die Hiungnu hatten<br />

sich durch räuberische Einfälle eine Schreckensherrschaft über die Völker des Tarym-<br />

Beckens gesichert. Alle diese hatten ein Interesse an ihrer Niederwerfung; aber kein Volk<br />

konnte, wie man glaubte, in gleichem Maass Rache gegen sie brüten, wie die Yue-tshî;<br />

denn aus dem Schädel ihres im Jahre 157 erschlagenen Königs war ein Trinkgefäss gemacht<br />

worden. Sie mussten als Bundesgenossen gewonnen werden.<br />

Ein General Namens Tschang-kiën wurde beauftragt, sie in ihren neuen Wohnsitzen<br />

aufzusuchen. Seine Reise ist von hohem Interesse, denn sie ist die erste chinesische Expedition<br />

nach fernen Gegenden im Westen, von der wir Kunde haben. Wahrscheinlich<br />

war es<br />

in der That die erste; denn der Bericht hat die Färbung einer abenteuerlichen Entdeckungsreise<br />

nach ganz unbekannten Ländern (ich folge der Erzählung im 123sten Buch des<br />

Sse-ki von Sz’ma-tsiën nach der dankenswerthen Uebersetzung von Brosset ... 1828, p. 418–<br />

450, da dieser Bericht nur 40 Jahre nach der Aussendung von Tschang-kiën geschrieben<br />

wurde und in hohem Grade das Gepräge der ungeschminkten Wahrhaftigkeit trägt; eben-<br />

so benutze ich die von Brosset berechneten Jahreszahlen, nach welchen<br />

die Gesandtschaft<br />

im Jahre 127 zurückkehrte, also 139 auszog, während sie gewöhnlich, nach Ma-twan-lin, in<br />

die Jahre 136 bis 123 verlegt wird).<br />

Um das Jahr 139 verliess Tshang-kiën seine Heimath mit einem Uiguren Namens<br />

Tshung-i, welcher wahrscheinlich mit manchen Wegen in Central-Asien bekannt war, und<br />

einer Begleitung von 100 Mann. Nach zehnjähriger Gefangenschaft bei den Hiungnu entkamen<br />

sie und setzten ihre Reise nach dem Reich Ta-wan am Yaxartes fort, wo sie die Yuetshî<br />

vermutheten. Sie hörten, dass diese weiter, nach dem Oxus, in das Land der Ta-hiâ,<br />

gezogen seien ... Dort, berichtet er, fand er die Yue-tschî nördlich vom Fluss Wei (Oxus)<br />

wohnend ... Sie empfingen ihn gut, erklärten aber, dass ihr Land fruchtbar sei, und sie<br />

darin glücklich, friedlich und der Plünderung wenig ergeben lebten; sie konnten sich nicht<br />

entschliessen, in ihre früheren rauhen und öden Wohnsitze zurückzukehren, um die alten<br />

Feinde zu bekriegen. Das Nomadenleben hatten sie noch nicht abgelegt.<br />

Auf dem Rückweg kam Tschang-kiën nach dem Gebirge Ping-shan und wollte von da<br />

durch das Land der Kiang gehen, wurde jedoch von den Hiungnu gefangen genommen<br />

und entkam nach einem Jahr. Erst im Jahre 127 kehrte er mit Einem aus seinen 100 Begleitern<br />

an den kaiserlichen Hof zurück. Sein Hauptzweck war verfehlt. Er hatte die gewünschten<br />

Bundestruppen nicht mitgebracht. Aber er hatte Wichtigeres erreicht. Denn er<br />

konnte seinem Kaiser über die Existenz grosser Völker im fernen Westen berichten ...<br />

Nach Feststellung der Lage von Ta-wan lassen sich die Positionen der anderen Völker<br />

und Reiche annähernd bestimmen. Die Khang-kiu und Yen-tsai breiteten sich am Yaxartes<br />

abwärts aus. Die ersteren nomadisierten wahrscheinlich<br />

in den Gegenden von Taschkent,<br />

Tschemkent<br />

und Turkestan, während die Yen-tsai den Unterlauf des Stromgebietes bis<br />

zum Aralsee einnahmen. Die Khang-kiu hatten im Nordosten die Usun zu Nachbarn. Mit<br />

der Residenz am Issyk-kul, breiteten sich diese wahrscheinlich am Nordfuss des Alexandergebirges<br />

und des Karatau über Talas hinaus aus. Südwestlich von den drei grossen<br />

Reichen am mittleren und unteren Yaxartes folgten einige kleine Reiche, deren Namen uns<br />

nicht aufbewahrt sind.<br />

In dem Thal von Samarkand begann das ehemalige Gebiet der Ta-hiâ, von dessen<br />

nördlichem Theil nun die Yue-tshî Besitz genommen hatten. Die letzteren scheinen sich<br />

— 9 —

ebenso nach Westen, gegen das jetzige Bokhara, als nach Südwesten bis zum Oxus ausgebreitet<br />

zu haben, während das unkriegerische, verweichlichte Volk der Ta-hiâ die reichen<br />

Handelsplätze im Süden des Oxus nebst grossen Strecken auf dem rechten Ufer desselben<br />

inne hatte ... Die Yue-tshî breiteten sich aus und mögen die Ta-hiâ nach Westen gedrängt<br />

haben, da die Dahae oder Daoi der griechischen Schriftsteller am Kaspischen Meer wohnten<br />

...<br />

With so many contradictory explanations of one and the same source text, it was<br />

about<br />

time for another — closer — look at Shiji 123 by those who read Chinese.<br />

SPECHT does, and, in 1883: 348, explains:<br />

Les Yué-tchi, ou Indo-Scythes, qui habitaient primitivement entre le pays des Thun-<br />

Hoang et le mont Ki-lian (les monts Célestes), furent vaincus, en 201 et en 165 avant notre<br />

ère, par les Hioung-nou. Ils s’enfuirent au-delà des Ta-Ouan, battirent les Ta-hia de la Bactriane<br />

dans l’ouest, et les subjuguèrent. Leur roi fixa sa résidence au nord de l’Oxus; c’est<br />

dans cette contrée que Tchang-kian, ambassadeur chinois, les trouva en 126 avant notre<br />

ère. Après le départ de ce dernier, la ville de Lan-chi, capitale des Ta-hia, tomba au pouvoir<br />

des Grands Yué-tschi qui s’établirent définitivement dans la Bactriane …<br />

Here the Ruzhi 月氏 are termed “Indo-Scythians” — an epithet which shall reap-<br />

p ear regularly from now on. The mistaken appellation “Skythai” for the 月氏 dates<br />

b ack to Strabo, for whom nine tenth of the Asian Continent were yet unknown. In his<br />

t ime, the 月氏 were known to have come from regions just beyond the Jaxartes. The<br />

G ræco-Roman historian, therefore, took it for granted that the Ruzhi 月氏 were just<br />

another<br />

branch of the Sakas — called Scythians by the earliest Greek historians like<br />

H erodotos. When the easternmost Saka tribe, the Sakaraukai/Sacaraucae, finally<br />

r eached India in the first century BCE, it was natural to name these genuine Scythians<br />

“ Indo-Scythians.”<br />

The Ruzhi 月氏, however, have<br />

never been Scythians — let alone Indo-Scythians.<br />

Two<br />

thousand years after Strabo we know that the 月氏 originated, not from regions<br />

near<br />

the Jaxartes, but thousands of kilometers further east from regions north and<br />

w est of the Yellow River where they were neighboring the proto-Huns and the archaic<br />

Chinese.<br />

The Ruzhi 月氏 came, not from Central Asia, but from the Far East and ori-<br />

ginally<br />

were, not of Indo-European, but of Mongoloid stock (see below, p. 71). They<br />

surely<br />

looked a great deal different from any of the Scythian tribes of our classical<br />

sources<br />

with whom the 月氏 only shared the pastoral way of life.<br />

The appellation “Indo-Scythians” for the Ruzhi 月氏 is a gross misnomer. It can be<br />

traced<br />

back to our classical Western and Eastern sources and the painfully difficult<br />

and time-consuming process towards their correct interpretation in modern<br />

times.<br />

In the Periplus, composed around the middle of the first century CE, the Indus Val-<br />

ley,<br />

from the Kabul River down to the Erythræan Sea, is still simply called Skythia. In<br />

t he early first century CE this part of India was in the hands of the foreign Parthians<br />

w ho had inherited it from the equally foreign Sakas or Scythians. The name “Skythia,”<br />

then,<br />

for a country formerly occupied by the Sakaraukai, a branch of the nomadic Scy-<br />

thians,<br />

makes good sense.<br />

(CASSON<br />

1989: 73–74; 77) Periplus 38–39; 41<br />

After this region ... there next comes the Met¦ d taÚthn t¾n cèran ... kdšcetai <br />

seaboard<br />

of Skythia, which lies directly to paraqal£ssia mšrh tÁj Skuq…aj par' aÙtÕn<br />

the<br />

north; it is very flat and through it keimšnhj tÕn boršan, tapein¦ l…an, x ïn<br />

flows the Sinthos River, mightiest of the potamÕj S…nqoj, mšgistoj tîn kat¦ t¾n<br />

rivers<br />

along the Erythraean Sea ...<br />

'Eruqr¦n q£lassan potamîn ...<br />

The<br />

river has seven mouths, narrow and `Ept¦ d oátoj Ð potamÕj œcei stÒmata, lept¦<br />

full of shallows; none are navigable except d taàta kaˆ tenagèdh, kaˆ t¦ m n ¥lla di£ -<br />

the<br />

one in the middle.<br />

ploun oÙk œcei, mÒnon d tÕ mšson, f' oá kaˆ<br />

At<br />

it, on the coast, stands the port of trade tÕ paraqal£ssion mpÒriÒn stin Barbari-<br />

— 10 —

of<br />

Barbarikon.<br />

There<br />

is a small islet in front of it; and be-<br />

hind<br />

it, inland, is the metropolis of Skythia<br />

itself,<br />

Minnagar.<br />

The<br />

throne is in the hands of Parthians,<br />

w ho are constantly chasing each other off<br />

it.<br />

Vessels moor at Barbarikon, but all the<br />

cargoes<br />

are taken up the river to the king<br />

at the metropolis ...<br />

The part inland, which borders on Skythia,<br />

is<br />

called Abêria, the part along the coast<br />

Syrastrênê.<br />

kÒn.<br />

PrÒkeitai d aÙtoà nhs…on mikrÒn, kaˆ kat¦<br />

nètou mesÒgeioj ¹ mhtrÒpolij aÙtÁj tÁj Sku-<br />

q…aj Minnag£r:<br />

basileÚetai d ØpÕ P£rqwn, sunecîj ¢ll»louj<br />

kdiwkÒntwn.<br />

T¦ m n oân plo‹a kat¦ t¾n Barbarik¾n diorm…zontai,<br />

t¦ d fort…a p£nta e„j t¾n mhtrÒ-<br />

polin<br />

¢nafšretai di¦ toà potamoà tù basile‹<br />

...<br />

TaÚthj t¦ m n mesÒgeia tÍ Skuq…v sunor…<br />

zonta 'Abhr…a kale‹tai, t¦ d paraqal£ssia<br />

Su[n]rastr»nh ...<br />

More than a century after the unknown author of the Periplus, but writing in the<br />

s ame Alexandria in Egypt, it is the erudite Klaudios Ptolemaios who, in his Geography<br />

of about 170 CE, introduces the appellation “Indoskythia.” He uses the name<br />

for the<br />

very<br />

same region — the lands on both banks of the Indus River from where the latter<br />

receives the waters of the Kabul River down to the ocean. Up north, Ptolemaios had<br />

named two other geographic regions “Skythia”: the “Skythia this side of the Imaon<br />

Mountains” and the “Skythia beyond the Imaon Mountains.” This may have been the<br />

simple reason why he wanted to give the Skythia in India a more dictinct name and so<br />

change the name in the Periplus, Skythia, to “Indoskythia.” As far as these classical<br />

writers were concerned, the name Skythia/Indoskythia had a lot to do with the Sakas<br />

or Scythians — and nothing with the Ruzhi 月氏. The latter arrived on the scene some<br />

time after the Sakas: in any case after the name “Skythia” had already been applied<br />

to the Panjab and the lower reaches of the Indus River.<br />

(MCCRINDLE 1885: 136)<br />

India within the (river) Ganges ...<br />

And furhter, all the country along the rest of the<br />

course of the Indus is called by the general name<br />

of Indo-Skythia.<br />

Of this the insular portion formed by the bifurcation<br />

of the river towards its mouth is Patalênê, and<br />

and the region above this is Abiria, and the region<br />

about the mouths of the Indus and Gulf of Kanthi is<br />

Syrastrênê ...<br />

Geographia 7.1.55<br />

TÁj ntÕj G£ggou 'IndikÁj qšsij ...<br />

P£lin ¹ m n par¦ tÕ loipÕn mšroj<br />

toà 'Indoà p©sa kale‹tai koinîj m n<br />

'Indoskuq…a,<br />

taÚthj d ¹ m n par¦ tÕn diamerismÕn<br />

tîn stom£twn Patalhn»,<br />

kaˆ ¹ Øper-<br />

keimšnh aÙtÁj 'Abir…a, ¹ d perˆ t¦<br />

stÒmata toà 'Indoà kaˆ ¹ perˆ tÕn<br />

K£nqi kÒlpon Surastrhn» ...<br />

MCCRINDLE, in his translation of Ptolemaios’ Indian chapters, 1885: 136–139, writes a<br />

short comment on the name “Indoskythia”: it shows that the greatest misunderstandings<br />

started in modern times:<br />

Indo-Scythia, a vast region which comprised all the countries traversed by the Indus,<br />

from where it is joined by the river<br />

of Kâbul onward to the ocean ...<br />

The period at which the Skythians first appeared in the valley<br />

which was destined to<br />

bear their name for several<br />

centuries has been<br />

ascertained with<br />

precision from the Chi-<br />

nese sources. We thence gather that a wandering<br />

horde of Tibetan extraction called Yuei-<br />

chi or Ye-tha in the 2nd century B.C. left Tangut,<br />

their native country, and, advancing west-<br />

ward found for themselves a new home amid<br />

the pasture-lands of Zungaria. Here they<br />

had been settled for about thirty years when<br />

the invasion of a new horde compelled them<br />

to migrate to the Steppes which lay<br />

to the north<br />

of the Jaxartes. In these new seats they<br />

halted for only two years, and in the year 128<br />

B.C. they crossed over to the southern bank<br />

of the Jaxartes where they made themselves<br />

masters of the rich provinces between that<br />

river and the Oxus, which<br />

had lately before belonged to the Grecian kings of Baktriana.<br />

This new conquest did not long satisfy their<br />

ambition, and they continued to advance<br />

— 11 —

southwards till they had overrun in succession Eastern<br />

Baktriana, the basin of the Kôphês,<br />

the basin of the Etymander with Arakhôsia,<br />

and<br />

finally the valley of the Indus and Syras-<br />

trênê. This great horde of the Yetha was divided<br />

into several tribes, whereof the most pow-<br />

erful was that called<br />

in the Chinese annals Kwei-shwang. It acquired<br />

the supremacy over<br />

the other tribes, and gave its name to the kingdom<br />

of the Kushâns ... These Kushâns of the<br />

Panjâb and the Indus are no others than the<br />

Indo-Skythians of the Greeks. In the ›Râjatara„gi‡î‹<br />

they are called Sâka and Turushka ( Turks) ...<br />

This is one example of how the early translations<br />

of Shiji 123 — at that time avail-<br />

able in French and Russian only — reached<br />

the desk of an English scholar: the broad<br />

outline is there, but the details are in shambles. The<br />

geography in the Chinese narra-<br />

tive is better understood than the chronology.<br />

This is strange because the Chinese his-<br />

torians are extremely careful and efficient<br />

in their methods of dating important facts<br />

and events. But<br />

it is there all given more si nico — that is the greatest barrier. In this<br />

short exposé<br />

the Eastern Ruzhi 月氏 merge with the Central Asian Sakas. In this way<br />

the 月氏 become the conquerors of Sakastana (Arachosia) and later the Indo-Scythians<br />

of the Panjab. It took time to correct these early confused misconceptions.<br />

MCCRINDLE, I like to note here, has one rare observation to offer: he states that the<br />

Ruzhi 月氏 conquered, not Bactria, but Eastern Bactriana — or Ta-hia/Daxia 大夏.<br />

SPECHT’s equation Ta-hia = Bactriana is of course a great improvement over RÉMU-<br />

SAT’s first guess Ta-hia = Massagètes or “Grands Gètes” (Goths). Short two years later<br />

MCCRINDLE comes close to hitting upon a perfect Ta-hia = Eastern Bactriana — if only<br />

he had been able to read Zhang Qian’s report in the Shiji himself. Instead, from now<br />

on Ta-hia = Bactria will be repeated by just about every author. However, in order to<br />

understand the complex story of the Ta-hia (Daxia 大夏) or Tochari properly, the<br />

equation with Bactria is not good enough: indeed it is still misleading. It suggests that<br />

the Ruzhi 月氏 conquered the whole of Bactria which — as this study will show —<br />

they were unable to do for a long time (see below, p. 56).<br />

Ta-hia 大夏 cannot be the<br />

Chinese transcription of the name Bactria. Ta-hia ( Daxia), the Chinese Standard Histo-<br />

ries (e.g. the New Tangshu) tell us, was later called<br />

Tu-ho-lo (Tuhuoluo) 吐火羅 =<br />

Tocharistan.<br />

NEUMANN, 1837: 181, translated:<br />

Tu ho lo … vor Al ters war dies das Land der Ta hia —<br />

in the Chinese original text very clearly given as:<br />

吐火羅 … 古大夏地 or: Tu-ho-lo ... (is) the country<br />

of the old Ta-hia.<br />

Tu-ho-lo, it was soon universally recognized, is the Chinese name for To-cha-ra. It<br />

is not Bactria, but only the easternmost part of it, the country later called Toxårestån<br />

(and<br />

also Taxårestån) by Arab authors. That this very important clarification has constantly<br />

been overlooked has greatly helped to confuse the issue. But what is of interest<br />

for us here, is indeed Specht’s statement<br />

that Zhang Qian arrived at the Oxus River in<br />

the year 126. Coming from a Sinologist, this is disappointing. It is unfounded and not<br />

much<br />

more than a guess.<br />

In another posthumously published work, the Non-sinologist VON G UTSCHMID,<br />

1888:<br />

59– 62, explains his own understanding of the Chinese sources:<br />

Es stünde schlimm um unser Wissen von dem Untergange jenes in ferne Lande versprengten<br />

Bruchtheils des griechischen Volkes, wenn nicht die Politik der chinesischen Regierung<br />

ein sehr lebhaftes Interesse an den Bewegungen der innerasiatischen Nomaden<br />

genommen hätte: diesem Interesse verdanken wir den Bericht eines chinesischen Agenten<br />

… Nach diesen Quellen wohnten die Yue-tshi, ein den Tibetanern verwandtes Nomadenvolk,<br />

ehedem zwischen Tun-hwang (d.h. Sha-tscheu) und dem Ki-lien-shan und wurden<br />

hier, wie alle ihre Nachbarvölker, 177 von dem türkischen Volke der Hiung-nu unterjocht.<br />

Eine Erneuerung des Kampfes zwischen 167–161 bekam ihnen übel: Lao-shang, der<br />

Shen-yu oder Gross-chan der Hiung-nu, erschlug ihren König Tshang-lun [the name of this<br />

— 12 —

king is not known — GUTSCHMID is quoting in the wrong place the mistaken translation of<br />

BROSSET 1828: 424 for the name of the chanyu Mo-du] und machte sich aus seinem<br />

Hirnschädel eine Trinkschale; sein Volk aber trat die Wanderung nach Westen an …<br />

Die sogenannten Grossen Yue-tshi zogen in das später von den Usun benannte Land<br />

(das Land am See Issyk-kul). Hier trafen sie ein anderes Nomadenvolk, die Sse, und schlugen<br />

ihren König, der mit seinem Volk zur Flucht nach Süden genöthigt ward …<br />

Die Grossen Yue-tshi liessen sich darauf im Lande der Sse nieder, erfreuten sich aber<br />

des<br />

Besitzes nur kurze Zeit: der Kun-mo oder König der Usun, eines Volkes, das westlich<br />

von den Hiung-nu gewohnt hatte, schlug die Grossen Yue-tshi und nöthigte sie, weiter nach<br />

Westen zu wandern.<br />

Die Zeit der Vertreibung der Yue-tshi aus dem Lande am Issyk-kul lässt sich genau datieren;<br />

dem chinesischen Agenten wurde während seiner Internierung bei den Hiung-nu<br />

(138–129) die Geschichte des Gründers des Reichs der Usun mitgetheilt: derselbe sei beim<br />

Tode des Shen-yu der Hiung-nu in ein fernes Land gegangen, habe sich in diesem niedergelassen<br />

und von da an dem Shen-yu den Gehorsam aufgesagt (Sse-ma-tsien im Nouv.<br />

Journ. Asiat. II, 429). Der einzige Shen-yu aber, der in dieser Zeit gestorben ist, war Laoshang,<br />

der 160 starb (WYLIE im Journ. of the Anthrop. Inst. III, 421), so dass also die Vertreibung<br />

der Grossen Yue-tshi in dieses oder das folgende Jahr zu setzen ist. War der Aufent-<br />

halt<br />

derselben am Issyk-kul ein so kurzer, so begreift es sich, wie er dem ältesten Berichterstatter<br />

ganz verborgen hat bleiben können …<br />

Die Grossen Yue-tshi, sagt der jüngere Bericht, wandten sich nun nach Westen, wo sie<br />

sich Ta-hia (d.i. Baktrien) unterwarfen; auch aus den Worten der älteren Quelle “geschlagen<br />

von den Hiung-nu hätten sie sich über Gross-Wan (Ferghana) hinaus entfernt, das<br />

Volk von Ta-hia geschlagen und sich unterworfen und alsbald ihr königliches Lager nördlich<br />

vom Flusse Wei (d.i. Oxus) aufgeschlagen,” folgt durchaus nicht nothwendig, dass der<br />

Einbruch über Gross-Wan erfolgt ist (noch weniger ein langer Aufenthalt daselbst, wie er<br />

angenommen zu werden pflegt). Vielmehr scheinen die chinesischen Berichte darauf zu<br />

führen, dass die Grossen Yue-tshi schon 159 direct in Sogdiana eingedrungen sind, also gerade<br />

in der Zeit der inneren Kriege, welche die Macht des Eukratides untergruben. Vielleicht<br />

ist die Eroberung<br />

eine allmähliche gewesen, da ja Baktrien im Jahre 140 noch als<br />

unabhängig<br />

vorkommt.<br />

Als die Yue-tshi schon in ihrer neuen Heimath sich niedergelassen<br />

hatten, schickte der<br />

Kai ser von China einen Agenten in der Person des Tshang-kien zu ihnen, in der Absicht, sie<br />

zur Rückkehr in ihre alte Heimath zu bewegen … Tshang-kien fiel den Hiung-nu in die<br />

Hände, entkam aber 129 nach Gross-Wan und ward von da durch das Land<br />

Khang-kiu (am<br />

mittleren<br />

Sir-Darja) zu den Yue-tshi geleitet. Diese aber fühlten sich in dem fruchtbaren,<br />

räuberischen Einfällen wenig ausgesetzten, von einer friedlichen Bevölkerung bewohnten<br />

Lande, das sie in Besitz genommen hatten, zu wohl, als dass sie auf die chinesischen Anträge<br />

eingegangen wären. Vergeblich begab sich Tshang-kien nach Ta-hia; er musste nach<br />

1-jährigem Aufenthalt (128–127) unverrichteter Sache heimkehren und hatte auf der Rückreise<br />

noch das Missgeschick, den Hiung-nu ein zweites Mal in die Hände zu fallen; erst 126<br />

langte er wieder in China an.<br />

Auf diesen Mann gehen fast ausschliesslich die lehrreichen Schilderungen von Land und<br />

Leuten zurück, welche die chinesischen Historiker uns liefern. Die Schilderungen sind so<br />

charakteristisch, dass sie die empfindliche Schwäche der chinesischen<br />

Berichterstattung,<br />

die<br />

aus ihrer Unfähigkeit, die Laute fremder Sprachen gehörig wiederzugeben, entspringende<br />

Willkür in ihrer geographischen Nomenclatur — die damals noch viel schlimmer<br />

war als in späteren Zeiten —, fast völlig wieder gut machen ... Namensanklänge haben<br />

hier mehr geschadet als genützt; selbst richtige Gleichungen hat man oft aus falschen<br />

Gründen gemacht, wie “Ta-hia = Baktrien” von den Dahen (die nie in Baktrien gewohnt<br />

haben) ...<br />

Here we have an Orientalist who had to read the Chinese sources in translation. Yet,<br />

he<br />

shows a clear understanding of their contents. The only really important informa-<br />

tion<br />

VON GUTSCHMID was lacking is that “Ta-hia” was not simply Bactria, but only its<br />

— 13 —

e astern part — the country later called Tocharestan. With this in mind he would have<br />

grasped<br />

that in the year 140 BCE not necessarily all of Bactria was still independent<br />

u nder Greek kings, but only the country around the capital Bactra in the West.<br />

The<br />

eastern<br />

part of Bactria had already fallen into the hands of those nomads who now —<br />

v ery shortly before Zhang Qian reached Daxia-Tochara — had lost this part of fertile,<br />

civilized, well populated Bactria, i.e. Tocharestan, to the superior 月氏. These first<br />

nomad<br />

conquerors cannot have been the Tocharians — for the Tocharians were still<br />

there:<br />

they are described as well settled on the land and as good traders, but weak<br />

fighters<br />

— the first wave of nomad conquerors, of which the Shiji knows nothing be-<br />

c ause Zhang Qian had missed these early invaders by a very short period of time, had<br />

alr eady swept across Daxia. In this first déluge the Greek armies and the last Greek<br />

sovereigns<br />

had disappeared from Tocharestan. Terrified by the reappearance of the<br />

Ruzhi<br />

月氏, the faster and hardier horseback archers from an unknown world — the<br />

F ar Eastern Oikumene — the first-wave conquerors had disappeared, too, and had left<br />

behind<br />

a country which was now without a king.<br />

The victorious 月氏 quickly filled that vacuum. But it was all still very new. The<br />

R uzhi 月氏 had barely erected their provisional seat of government as a tent city on<br />

t he near side of the Oxus River when the envoy of Han emperor Wu appeared before<br />

t heir leader — who was the son of that unfortunate king whom the Xiongnu had slain<br />

more than thirty years previously. The mysterious<br />

first nomad conquerors of Tochara<br />

can hardly have been any other people than the one which the 月氏 had carried before<br />

them<br />

ever since the lands on the upper Ili River: that particular tribe of the Saka con-<br />

f ederacy which has been variously called Sakarauloi / Sakaraukai, Sarancae / Saraucae,<br />

[ Saka-] Aigloi / [Saka-] Augaloi, Sagarauloi, Sacaraucae, or Sakaurakai Skythai in the<br />

W estern, and simply Sai-wang (older Sak-wang) 塞王 in the Eastern historical sources.<br />

Chinese 塞王 has in the past often been misunderstood to mean “the king (s) of the<br />

Sai/Sak”<br />

— with consequences that turned out to be very misleading. This reading and<br />

translation<br />

was a capital blunder (see below, pp. 42, 43).<br />

FRANKE, 1904: 54–55, explains:<br />

Die verschiedenen Varianten für den Namen des Volkes, die sich bei den westlichen Autoren<br />

finden ... legen den Gedanken nahe, daß ›wang‹ einen Bestandteil des Namens bildete,<br />

also ›Saka-wang‹, und daß dadurch ein besonderer Stamm der Saka bezeichnet werden<br />

sollte.<br />

2<br />

F.W.K. MÜLLER, 1918: 577 , strongly underlines this reasoning:<br />

塞, jetzt zwar im Norden ›Sai‹ gesprochen, lautet aber noch in Canton ›sak‹. ›Sak‹ war<br />

die ältere Aussprache, wie die buddhistische Transkription für Upâsaka lehrt: U-pa-sakka<br />

優婆塞迦. Dass ›Sai-wang‹ ein Name sein müsse, hat FRANKE mit Recht hervorgehoben.<br />

Seine Darlegung wäre noch schlagender gewesen, wenn er den Originaltext hinzugefügt<br />

hätte:<br />

昔<br />

大 月氏西君大夏<br />

而 塞王南君罽賓<br />

匈奴破大月氏 In alter Zeit besiegten die Hiung-nu die großen Yüe-tšï,<br />

die großen Yüe-tšï machten sich im Westen zu Herren von Tai-Hia,<br />

und die Sak-wang machten sich im Süden zu Herren von Ki-pin.<br />

Da in den beiden ersten Sätzen keine Rede von Königen ist, wird auch im dritten Satze<br />

王 nicht König bedeuten, sondern zum Namen gehören ...<br />

“Le grand déchiffreur berlinois” (MEILLET on MÜLLER) makes an intelligent state-<br />

m ent here. Of the Chinese name Saiwang/Sakwang 塞王 the first part, 塞, is clearly a<br />

transcription of Sak(a-), whereas the second part, 王, meaning “king” and read wang,<br />

is rather<br />

strange in at least two respects. It does not recall the second part of the Western<br />

name –raukai (*rawaka, “swift”) and it is a very common character in Chinese —<br />

— 14 —

whereas in transcribing foreign names the Chinese show a marked tendency to use<br />

rare or even obsolete characters. The 王 in 塞王 might therefore be a scribal error<br />

which happened early and was not corrected by later scribes because they had no way<br />

to check in all the many cases of little-known foreign names. I find that De Groot, 1926:<br />

25, has discussed the problem at greater length:<br />

Das Zeichen 塞 lautet sowohl ›sik‹ wie ›sak‹, und daß dies lange vorher der Fall war,<br />

zeigt uns die Behauptung des Jen Ši-ku (HS 61, Bl. 4), daß es nur eine andere Schreibung<br />

für 釋 ›Sik‹ ist, Buddhas Stammname Sakja, der in der Tat in China immer durch dieses<br />

Zeichen oder durch 釋伽 ›Sak(Sik)-kia‹ wiedergegeben worden ist. Was haben wir uns nun<br />

bei dem Zeichen 王 ›ong‹ zu denken? Zunächst befremdet es, daß für die Transkription<br />

eines ausländischen Volksnamens gerade ein so alltägliches Zeichen, das einfach “König”<br />

bedeutet, gewählt und dadurch die Tür für Mißverständnisse weit geöffnet wurde; denn<br />

ein jeder mußte seitdem aus Sak-ong ohne Bedenken “König der Sak” lesen, was der Textschreiber<br />

gewiß nicht gewollt haben kann. Man ahnt somit, daß hier ein Schreibfehler vorliegt<br />

und ursprünglich das ähnliche 圭 ›ke‹ gestanden haben kann, das dann später durch<br />

kluge Gelehrte, die in dem Text das betreffende Volk auch bloß als ›Sak‹ erwähnt fanden,<br />

für einen Fehler für ›Sak-ong‹, “König der Sak” gehalten und dementsprechend “verbessert”<br />

wurde. Die Zeichen 圭 sowie 跬, 閨 und 奎, worin es als phonetisches Element steht,<br />

lauten ›ke‹; 佳 aber lautet ›ka‹, und 罣, 卦 und 挂 werden ›koa‹ ausgesprochen. Der chinesischen<br />

Transkription zufolge kann also das in Frage stehende Volk ›Sak-ke‹ oder ›Sik-ke‹,<br />

›Sak-ka‹ oder ›Sik-ka, ›Sak-koa‹ oder ›Sik-koa‹ geheißen haben.<br />

De Groot makes it certain here that the translation “the kings of the Sai” for Saiwang<br />

塞王 must be a mistake — as explained in 1904 by Franke and 1918 by F.W.K.<br />

Müller. But when he goes on to suggest that we should read 塞王 simply as Sak–ka we<br />

cannot<br />

follow him. For in the Hanshu we find both Sai 塞 and Saiwang 塞王 (below,<br />

pp. 42, 43). These two hanzi 漢字, or Chinese characters, stand for the general designation<br />

“Saka” 塞 on the one hand and for the more specific<br />

tribal name “Sakaraukai”<br />

塞王 on the other. Chinese Saiwang<br />

塞王 is the equivalent of Latin Sacaraucae<br />