-by Greg Hoots-

Friedrich Meditz was born on May 24, 1929 in Buchel, a hamlet in the ethnic German enclave of Gottschee, located in the Lower Carniola region of Yugoslavia. Friedrich’s parents, Johann Meditz and Josefa Tramposh Meditz lived in the same rural community where their ancestors had lived since immigrating to that region from Germany six-hundred years prior.

In the six centuries before Friedrich’s birth, his family had farmed the same hills and lived on the same land; however, the political rule changed repeatedly throughout the enclave’s history, leaving its residents often adrift in a sea of no refuge. Gottschee, once part of the Holy Roman Empire, had been ruled by monarchs for centuries after the land had first been settled by German farmers in the 14th century. In the early 1800s the Gottschee enclave became a part of the Illyrian Provinces and was controlled by the Napoleonic French Empire for a period of ten years before the Gottscheer revolted against the French in 1809. In the years that followed, Gottschee became part of the Kingdom of Illyria, the Duchy of Carniola, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and then, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, as it was known when Friedrich Meditz was born.

The Johann Meditz family home at Buchel is seen in this photo dated October 10, 1941. Johann’s son, Rudolf, is seen standing in the doorway while Johann is seated with Rudolf’s wife on the bench. The family was coerced into leaving this home two months later.

Johann Meditz was eighteen years older than his wife, Josefa, as he had been married earlier and had several children when his first wife died, leaving him with kids to raise. He first hired Josefa as a governess, and eventually, Johann and Josefa married. The couple had five more children, four boys and a girl. In a few years, the older children started families of their own, leaving their parents with Rudolf, Karl, Anne, Heinrich, and Friedrich at home in Buchel.

After the war, Fred Meditz and his brother, Karl, returned to the Soviet-controlled Yugoslavia on a visit to see the place where they had been born. Their family home had been leveled by Allied bombing during the war, and Fred recovered this piece of stone from the rubble, the last remaining piece of their centuries-old family home.

While the Gottscheer were subjects of the Austrian royalty, most political decisions were local in nature, with town councils levying taxes for public services such as schools and fire protection. The Lower Carniola region of Yugoslavia contained forested mountain areas skirted by tillable foothills, which provided small farming tracts for the Gottscheer.

Many of the Gottscheer had, over the years, married Slovene spouses and adopted a language of their own, Gottscheerish, a unique dialect of German. While the cultural ties of their German heritage were strong for the Gottscheer, over the centuries they had developed their own unique culture, and few considered themselves German. They were the Gottscheer.

Friedrich Meditz, far right, poses in Buchel with his parents, Johann and Josefa Meditz, and his sister, Anne, circa 1940.

As the Third Reich’s conquest of Europe grew, the residents of Gottschee were almost ambivalent. The culture, itself, was one which was not unfamiliar with political realignment, and the residents of Gottschee were simple farmers living modestly off the land without respect to political powers, not unlike their ancestors had lived for centuries as their land had been repeatedly conquered, mortgaged, sold, and traded.

When Hitler took power in Germany in 1933, it was not long before the influence of the new German government was felt in neighboring Gottschee. The Third Reich’s plan was a long-range strategy, and the first element was to develop support among the youth of ethnic German regions of eastern Europe, including Yugoslavia. Youth development camps, sponsored by the Reich, were held in Germany in the winter months when the young men were not needed as farm laborers. Dozens of teenagers from Gottschee attended these youth camps which taught Nationalist Socialist ideology to the young attendees. Additionally, these young men were taught military discipline, organizational skills, and, above all, an undying loyalty for the Fatherland and the Fuhrer.

In Gottschee, small isolated elements of National Socialists began organizing early in the 1930s. Wilhelm Lampeter, born in Gottschee in 1916, became an avid nationalist while attending the development camps in “the Fatherland”, and he was expelled from secondary school for forming an illegal youth group with other National Socialist German students from Gottschee in 1932. A declassified dossier created by the Central Intelligence Agency tells of Lampeter’s association with the German SS, noting his early efforts as a Nationalist in Gottschee, saying, “He (Lampeter) was active within the National Socialist Students’ League dealing primarily with National Socialist education of young Gottschee farmers…He referred to himself as ‘Fuehrer der Gottscheer Jugend’” (translated: Leader of the Gottscheer youth). The longtime member of the Hitler Youth group persisted in his organization of the Gottschee youth, and by 1938 Lampeter was running for public office for control of the Gottschee local government.

Another element of the Nationalist movement in Gottschee was to find a common element of society to vilify in an effort to unify the Nationalist ranks. In Gottschee, it was the Slovenes who were chosen to become the enemy of the state. Members of the ethnic Slavic group were blamed for every woe in lives of the Gottscheer. The Nazis were eager to fuel this rift, as they had plans to cleanse eastern Europe of the Slovene population.

The youth movement swept the 1938 elections, and in January of 1939 Lampeter and his associates took control of the government in Gottschee. Simultaneously, the management of Gottschee City’s (now known as Kocevje) official newspaper, the Gottscheer Zeitung, was taken from its longtime publishers and placed in the hands of Herbert Erker, a close confidante of Lampeter. Richard Lackner, Lampeter’s second-in-command, was named head of the Gottschee Youth, a virtual carbon-copy of the Hitler Youth in Germany.

As the new leaders of the Gottschee government formed political alliances with the Reich, Erker’s Gottscheer Zeitung, began to take a more and more conciliatory position concerning Nazi control of the region, and soon the paper became the voice of the Third Reich in Gottschee.

In 1939 Wilhelm Lampeter formed the “Gottscheer Mannschaft” a paramilitary militia organization which was initially formed with 1,700 men, included in 25 “Sturms” or storms of troops. The members of the Mannschaft were uniformed in regular German army uniforms, each emblazoned with an armband bearing the colors of the Gottschee official flag. Associated with each Sturm was a youth organization to which every Gottscheer child was required to belong. All Gottscheer boys from age 7 through age 21 were required to belong to the Gottschee Youth. All members were given a uniform which mirrored the German Hitler Youth uniforms. All Gottscheer girls were organized in a similar group headed by Reich-trained Maria Rothel. For many of the children of Gottschee, these military uniforms were the first item of new clothing that they had ever owned. The new German-made military boots were, in many cases, the first new pair of shoes that many of the children had ever worn.

When the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was officially created on October 3, 1929, Alexander I, the former King of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, was named King of Yugoslavia. Five years after assuming the Yugoslav crown, King Alexander I was assassinated while on a state visit to France. Alexander’s heir to the throne was his eleven-year-old son, Peter II. Insofar as Peter was just a child, still in school, his second cousin, Prince Paul, was named Regent to manage the affairs of government until Peter II came of the age of eighteen.

On March 27, 1941 the Yugoslav military staged a bloodless coup, removing Prince Paul from his role in governing Yugoslavia. King Peter II was seventeen years of age at the time of the coup, and attempts were made to declare him of age in an effort to preserve the monarchy.

Such efforts were unsuccessful, when ten days later, on April 6, 1941 at 5:12 am, the German, Italian and Hungarian armies invaded Yugoslavia from all sides, as major cities, were bombed by the German Luftwaffe. Belgrade, the Yugoslavian capital city, was leveled in a three-day siege of bombing as Hitler launched Operation Retribution, the Reich’s response to the military coup. The Yugoslav army fought to defend their territory, however they were overwhelmed by six German army divisions supported by the superior Luftwaffe air power, and after only eleven days, the Yugoslav government signed an armistice and surrendered to Hitler. More than 300,000 Yugoslav soldiers were taken prisoner and sent to POW camps and labor camps in Germany. Immediately after the capitulation, life in Yugoslavia would never be the same, and as for the Gottscheer, they were well on their way to becoming a people without a country.

In Gottschee City and the smaller villages alike, long, red banners bearing the Nazi Swastika adorned public buildings, and German military vehicles filled with smartly dressed soldiers became commonplace throughout the enclave.

When the army of the Third Reich rolled into Gottschee, Friedrich Meditz was just eleven years old. Schools were immediately suspended as the two German youth organizations expanded into the enclave. The former Gottschee Youth organization became the Hitler Youth, and the Band of German Maidens organized the Gottscheer girls, as every child was taught to pledge their allegiance to the Fuhrer. The Mannschaft became a local arm of the German military.

One of the first acts of the new conquerors was to suspend all newspapers in the enclave. Everything that any Gottscheer could read was authored and printed in the Reich.

Just days after the Reich conquered Yugoslavia and divided the defeated nation between Germany, Italy, and Hungary, the announcement which defined the future for the Gottscheer came. The area of Lower Carniola that the Gottscheer had inhabited for more than 600 years was awarded to Italy who would assume control of the territory on January 1, 1942. The Gottscheer would all be resettled to the “Fatherland”, reunited with the Reich at the command of the Fuhrer. The citizens of Gottschee were astonished, dismayed, and in disbelief. They had lived for scores of generations on their land, and the prospect of “trading” their land for property in the Reich had little appeal for most.

Thus, began an intense campaign by the new Gottschee leaders, Lampeter, Lackner, and Erker to convince the Gottscheer to leave their homes. The newspaper ran numerous stories, promoting the benefits of resettlement, while at the same time warning of the consequences of resistance. The paper threatened that any Gottscheer who did not relocate would be sent to work camps in Abyssinia, an African nation (now part of Ethiopia) occupied by Italy. The Hitler Youth children were instructed to pressure their parents to relocate, and in the villages, threats were made to those who spoke in opposition to the resettlement.

One issue that bothered many of the Gottscheer was that in promoting the resettlement, the leadership refused to provide any specifics about the new land where the Gottscheer would be living. Commonly, it was just referred to as “the Fatherland.”

By early fall of 1941, most of the Gottscheer had made their decision concerning resettlement. Initially, the Reich inspected all of the prospective re-settlers, rejecting some 575 of the Gottscheer as unsuitable for resettlement. Those unfortunates, including individuals from unapproved ethnic groups and those of mixed marriages, were deported deep into Germany where they were imprisoned in work camps, never to return to their homes. About 600 of the Gottscheer refused to relocate, suffering considerably in the chaos that followed in Italian-occupied Yugoslavia. However, 11,576 of the Gottscheer decided to pack what belongings they could in crates, many taking a single horse, cow, or pig, and load themselves and their families on trains, bound for an unknown destination and an uncertain future in the Third Reich. By virtue of their resettlement, all of the Gottscheer who moved were “awarded” citizenship in the Reich.

The resettlement was planned to take place in the months of November and December of 1941, and 167 Gottscheer settlements were divided into 25 groups which were numbered “Go 1” through “Go 25”. Go 5, referred to as the Nesselthal group, contained residents from the settlements of Altfriesach, Buchel, Kummersdorf, Mitterbuchberg, Nesselthal, Neufriesach, Oberbuchberg, Reichenau, Tanzbuchel, and Untersteinwand. The Meditz family belonged to Go 5, among the first groups to be resettled in the Fatherland.

When the resettlement trains departed, most of the Gottscheer believed that they were to be resettled in Germany, or at the very least, in Austria, which had become part of the German state in 1938. They were all sadly mistaken. The train trip to the new land was slow; settlers’ trains were required to yield to any military trains on the tracks, and delays were frequent. When the re-settlers arrived at their new homeland, they were very disappointed. Rather than being resettled in the Fatherland, they had been moved only 40 miles to the northeast into the German-occupied portion of Yugoslavia near the town of Rann (now known as Brezice), located in the Sava Valley. The homes that they were to receive in trade for those which they abandoned were of a substandard quality, and the farmland, itself, was far less productive that the land of their forefathers. Worse yet, when the settlers arrived, they soon realized that they were moving into homes that had belonged to Slovenes who had been the victims of Nazi ethnic cleansing. More than 40,000 Slovenes who lived in the triangular area located between the confluences of the Krka, Sulta, and Sava Rivers were rounded-up, taken from their homes, their beds, and their dinner tables, and transported to work camps and concentration camps throughout the Reich. Gottscheer families moved into Slovene homes that had food in the pantries, feed in the barn, and in some cases, uneaten meals on the dining tables.

It soon became common knowledge to everyone that the Gottscheer had become party to the removal of the Slovenes, and many of the re-settlers felt considerable guilt over the situation. But, as all things had been in the eight months that had preceded the move, they were now living in the Third Reich, and resistance was futile, if not suicidal.

At Rann, the schools were operated and controlled by the Reich, and Hitler’s youth organizations played a huge role in the education system. At thirteen years old in 1942, Friedrich Meditz lived with his family in a home in the Rann Triangle, attended a German state school, and was a member of the Hitler Youth. His brother, Heinrich the closest sibling to Friedrich in age, was drafted into the German Army where he was soon killed in action.

When the Nazi invaders began their ethnic cleansing of the Slovene settlements in the Rann Triangle, some of the more fortunate Slovenes fled into the forested hillsides before the invaders could imprison them for transportation to labor camps in Germany. Two distinct groups of local opposition to the Reich occupation of Yugoslavia emerged after the 1941 invasion of the country. Josip Broz Tito, a communist revolutionary born in the Croatian region of Austria-Hungry, formed a guerrilla army which operated from the mountains of Yugoslavia, engaging in raids on Axis targets, including the ethnic German settlements at Rann. A second group of armed resistance to the German occupation was the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Slovenia, a small but effective group of Slovenes who engaged in guerrilla fighting in southeastern Yugoslavia. Both groups began as small bands of citizen-soldiers who persisted in their attacks against the German occupiers, despite their lack of supplies and arms.

After the surrender of Italy in 1943, both partisan groups acquired the weapons abandoned by the surrendering Italian army, and the membership in both resistance groups grew from a few hundred members to a few thousand members in a matter of months. In 1944 the two groups of Partisans combined their forces and by April of 1945 the Partisans numbered more than 800,000 troops.

With the increasing pressure brought on the German occupiers in Yugoslavia by the Partisans, the Reich turned to the local Gottscheer militia, the Mannschaft, to protect the re-settlements at Rann. At the same time, the Mannschaft had lost many members as the German regular army conscripted every available man into their ranks. While initially Mannschaft members were required to be 21-years old, that minimum age requirement was discarded as every available male was placed into the fight.

Friedrich Meditz, a member of the Mannschaft, poses for the photographer at Rann in 1943, having just turned fourteen years of age.

In 1943, Friedrich Meditz, barely fourteen-years old, was conscripted into the Mannschaft, issued a German army uniform, and thrown into the battlefield at Rann. By then, Tito’s Partisan army numbered in the tens of thousands, and unlike at the beginning of the conflict, the Partisans were now heavily armed while the Mannschaft struggled to provide a single rifle for every soldier. By 1944 the war on the ground in southeast Slovenia had begun to turn against the German occupiers. However, insofar as the Mannschaft members were “locals” who lived in the Rann Triangle, their focus became a defensive one as the Partisans attacked military targets and occupiers’ homes with impunity. The Mannschaft soldiers were reviled by the Partisans, seen as occupiers of the Slovene homes and judged as traitors to their native Yugoslavia in their support of the Reich. Mannschaft soldiers who were captured by the Partisan forces were routinely executed.

Five members of the Mannschaft, including Friedrich Meditz, second from right, pose for a photographer at Rann in this view from 1943.

By 1945, the Gottscheer re-settlers and their Mannschaft protectors were overwhelmingly outnumbered and outgunned at Rann, as the German army found itself at the end of its conquest. The Gottscheer at Rann were completely isolated from the news of the war and the world, having no newspapers, radio stations or any other method of learning the day’s events. The announcement of Adolf Hitler’s suicide in the Fuhrerbunker at Berlin was received by the Gottscheer with disbelief. Even more shocking was the news a week later that Germany had surrendered on May 7, 1945 at Reims, France.

The news came first to the members of the German military, including the Mannschaft. All members of the German army were ordered to lay down their arms and surrender to the Allied forces. By this time, the primary Allied forces in the former Yugoslavia were Josip Tito’s Partisans. While surrender to the British or American forces was considered the best alternative for the defeated Germans, surrender to Tito’s Partisans was very risky. German soldiers and the Mannschaft members discarded not only their weapons, but also their uniforms, military identification and anything that would identify them as members of the Reich, as thousands of German soldiers attempted to assimilate themselves among the civilian population in an attempt to escape their victors.

On May 8th, the word spread through Rann like wildfire. The war was over, Germany was vanquished, and all of the Gottscheer, considered to be enemy occupiers by the soon-to-be ruling Partisans, must leave Yugoslavia, forever. The Gottscheer were told to take only the most essential belongings with them on their exodus from their homeland. Most importantly, they must make haste. The next day the long lines of refugees began gathering for their journey. The heavily armed Partisans were carefully scrutinizing the refugees, hoping to ferret-out any Nazi soldiers who were attempting to escape the consequences of their roles in the Reich.

The group of settlers to which the Meditz family belonged were told that they must leave Yugoslavia, and their next destination would be a Displaced Persons Camp (DPC) in Austria. While some settlers began their journey with wagons packed with the meager possessions that had survived their first move and the war, Tito’s Partisans soon relieved them of all of their belongings. Anecdotal stories tell of Partisan soldiers stripping clothes and shoes from fleeing refugees. Within days of beginning their exodus, most of the Gottscheer were left with no belongings.

The journey for the caravans of refugees became more difficult with every day of travel. Food was scarce, if it could be found at all. The Partisans kept the caravans moving at gunpoint, and if any of the refugees died, there was no opportunity for families to bury their dead; they were just thrown to the side of the road.

The caravan to which the Meditz family belonged traveled 130 miles on foot until they finally crossed the Austrian border some twenty-miles south of Villach, their ultimate destination. The journey from Rann took nearly a month. Friedrich’s sixteenth birthday came and went while on the refugees’ road to Austria.

There were thousands of refugees attempting to enter Austria, and initially there was chaos along the border. Included in the millions of refugees in eastern Europe were Axis combatants and prisoners of war, concentration camp and labor camp prisoners, and the civilians residing in nations which were dissolved during the war. The refugees were sorted by classification and assigned to camps, generally. Former members of the German military, for example, were placed in separate camps, as were former prisoners of the Reich. Hundreds of Displaced Persons Camps were established in Germany, Austria, Italy, and other European nations in an effort to help the war’s refugees to return home. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) managed all of the refugee camps in Europe with assistance from the Red Cross; and the task was monumental. Camps were established in former military barracks, prisoner of war camps, and even some former concentration and labor camps.

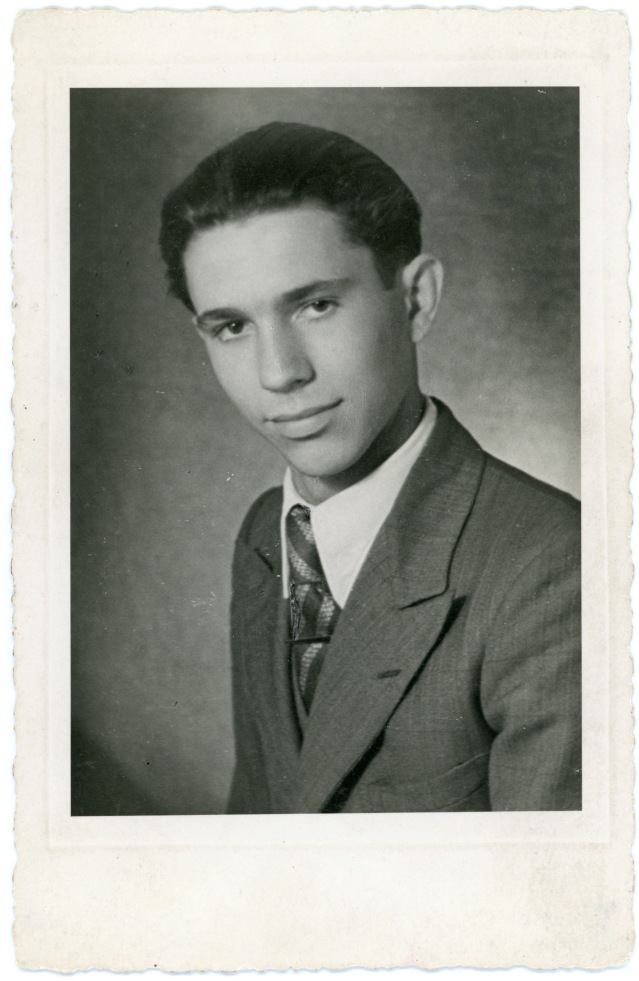

This portrait of Friedrich Meditz was produced on a postcard, identified as being taken in Villach, Austria on September 23, 1946, while he lived in the Displaced Persons Camp.

Friedrich and the Meditz family were placed in a DPC facility near Villach, Austria, arriving at the camp around June 1st. The first few weeks at the camp were spent in interviews with UNRRA staff, identifying all of the refugees and providing them with their most immediate needs, including shelter, food, clothing and medical care. An additional role of the camps was to provide educational opportunities to the refugees to assist them in preparing for their reentry to society.

This graduation certificate, dated November 3, 1948 signifies Friedrich Meditz’s completion of three years of school to become a journeyman stonemason. Friedrich was living at the Villach Displaced Persons Camp while he received his training as a mason.

In August of 1945, Friedrich enrolled in stonemason’s school at the Villach camp. The course required him to complete classroom work while serving an apprenticeship. His course began on August 8, 1945, and Friedrich graduated as a journeyman mason on November 3, 1948. A Villach builder, Rupert Sternath placed Friedrich in his employ, first as an apprentice working on construction sites, and ultimately, as a journeyman mason.

Friedrich Meditz, a stonemason, stands at the top of a Villach, Austria residence that is under reconstruction after bombing during World War II, circa 1949.

Friedrich Meditz was one of more than a million war refugees who had no home to which he could return. Officially, he was labeled “stateless”, although Austria provided refugees citizenship and a place to restart their lives. The Gottschee were no longer welcome in Yugoslavia, their family home for centuries. After completing his training as a mason, Friedrich decided that he wanted to immigrate to the United States. Friedrich began working in Villach on the many reconstruction projects underway in a city that saw more than 85% of its buildings damaged by British bombing during the war. He also began a long and arduous process of immigrating to America.

Friedrich Meditz, top row, right, stands on scaffolding of a residence in Villach being reconstructed after Allied bombing during World War II. Notice that the hod-carrier standing next to Fred is a female, and another stonemason stands on the lower level.

Insofar as the Meditz family had come to Austria with nothing but the clothes on their backs, they had no documents that were necessary for a person to travel to the United States, much less those required for immigration to America. In 1949, much of Friedrich’s time was spent working as a mason; but, at the same time he worked ardently with the UNRRA staff to acquire the necessary documents he would need to move to the United States.

This workbook was used by Friedrich Meditz while studying for his certification as a stonemason while living at a Displaced Persons Camp at Villach, Austria. Notice that the page is dated October 25, 1947.

Fred’s uncle, Matt Meditz, had immigrated to America from Gottschee in the early 20th century and had worked as a carpenter in Kansas City, Kansas. Friedrich had contacted Matt who agreed to be his sponsor in his quest to come to America. Friedrich’s uncle provided the money for the young immigrant’s transportation from Villach to Kansas City. Matt’s sponsorship guaranteed room and board for Friedrich, and with his connections in the building trades, Matt was able to find work for the young immigrant as a stonemason, building laid-stone basements for homes in Kansas City during a post-war building boom.

The canteen at the Villach Displaced Persons Camp where Friedrich Meditz and his family resided for five years is seen in this view from September of 1945. This view was sent to Friedrich by a family member “for your memory” and is dated September 11, 1950.

It took Friedrich more than a year to amass the documents required to become a U. S. immigrant. He applied for a birth certificate through the Austrian government to establish his parentage, and the place and date of his birth. Insofar as he had no passport that was valid, Friedrich’s attempt to process his immigration application was met with delays. Likewise, he had no visa that would permit him to travel in the jurisdiction of the various nations through which his path to immigration would take. Finally, Friedrich was issued a Swiss visa and a French visa in late June of 1950, but the Swiss visa was temporary, good for only 30 days, and he feared that he could not arrange sea transportation before the visa expired.

The United States Lines was founded in 1921, operating cargo ships between New York and destinations in England and Germany. The line operated with three ships in the 1920s as the company passed through the hands of three owners. Between 1932 and 1940 the line launched three new passenger liners, the Manhattan, the Washington and the America as the company became a leader in trans-Atlantic passenger transportation. In 1941 the ships of the United States Lines were converted to troop ships for the U.S. military, as the luxurious first-class accommodations of the ship were removed.

The roll of passengers aboard the S.S. Washington shows the departure dates from ports in England, France, and Ireland.

In 1946 the Washington was returned to the United States Lines after her military service, and the ship was refitted for commercial use. The United States Lines became one of several shipping companies who became the major carriers of immigrants to America, as the company established offices in Vienna to serve the needs of the many displaced persons in Europe. The Washington was returned to commercial service in February of 1947, providing accommodations for 1,106 passengers in a single class with a 565-man crew.

Friedrich Meditz stands on the deck of the S.S. Washington as the craft crosses the Atlantic Ocean in July of 1950.

After a considerable exchange of correspondence and documents, finally, in mid-July, 1950 Friedrich Meditz departed Villach on his long trip to America. He first travelled by train from Austria across France to La Havre, a port city in northern France. On July 22nd, 1950 Friedrich boarded the S.S. Washington at La Havre at the age of 21, bound for America.

Friedrich Meditz, right, poses with an unidentified passenger aboard the S.S. Washington, dated July 25, 1950.

Five days later, the S.S. Washington arrived at New York City with its immigrant passengers departing the ship at Ellis Island in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. Passengers departing the Washington were met by immigration officers who questioned each immigrant before doctors performed a “six-second physical” examination, during which any immigrants with physical deformities, diseases, or moral deficiencies were culled from the group for deportation. Immigrants who failed inspection were marked with chalk on their clothes, using a code that defined their shortcoming that denied them entry to the United States. Friedrich passed his physical with no difficulty.

In a matter of days, Friedrich was boarding a train bound for Kansas City, Kansas and a new life that awaited him. When Friedrich arrived at Union Station in Kansas City, he hailed a cab which took him to his Uncle Matt Meditz’s house located at 732 Broadview Street in Kansas City, Kansas. Matt Meditz was 72-years old when he sponsored his nephew as a landed immigrant. A carpenter by trade, Matt Meditz had made many friends in the construction industry in Kansas City, and he had many friends who were ethnic German immigrants.

Friedrich Meditz poses for a photo in Kansas City, Kansas shortly after his arrival to America in 1950.

Once a week, Matt Meditz held a card-playing party for a number of his friends. One member of his card-playing group was Frank Erker, a Gottscheer who had immigrated to America in 1913 at the age of seventeen. Erker worked as a millwright for Wilson & Co., a major meat packing plant in the Kansas City bottoms. Frank Erker and his wife, Mary, had two daughters, Dorothy and Mary Jean. Shortly after Friedrich Meditz’s arrival in Kansas City, he was introduced by his uncle to Mary Jean Erker. Friedrich spoke no English when he arrived in America, and he enrolled in an English language class held “down on Central” in Kansas City. In his spare time, Friedrich frequently attended the local movie theater, often sitting through multiple features, just to improve his understanding of the English language.

Mary Jean Erker, left, and Friedrich Meditz stop for refreshments while on a date in Kansas City, Kansas, circa 1951.

Friedrich and Mary Jean began dating in late 1950, and on July 14, 1951 the couple were married at St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in Kansas City, Kansas. Friedrich and Mary Jean had made wedding preparations for weeks before the event. At the same time, from late May through June, portions of the Kansas River were deluged with heavy flooding rains, and the river swelled in size. By the second week of July, Manhattan, Topeka, and Kansas City were all besieged with flood waters. Numerous bridges spanning the Kansas River were lost to the flood, and by July 12, the last automobile bridge connecting Kansas City, Kansas to Missouri was closed, deemed too dangerous to cross. Mary Jean’s wedding dress and all of the dresses for her bridesmaids had been purchased from a clothier in Kansas City, Missouri, and there was no way that the dresses could be delivered to the Kansas side. Mary Jean’s maid-of-honor, Lou Ann Scherzer, knew the Wyandotte County Sheriff, Red Edwards, and the sheriff drove Lou Ann across the bridge to meet a clothing store representative at the Missouri end of the span before returning to the Kansas side. The newlywed couple moved to 717 Orville Avenue in Kansas City. Friedrich found plenty of work in Kansas City as there was a strong demand for new homes.

Friedrich and Mary Jean Meditz, pose with the groomsmen and bridesmaids following the Meditz wedding on July 14, 1951. Seen here from left to right are Tony Preston, Eugene Stalzer, Friedrich Meditz, Mary Jean Meditz, Dorothy Whiles, and Lou Ann Scherzer. The bride’s gown and bridesmaids’ dresses barely made it to the wedding.

Spring of 1954 found Friedrich and Mary Jean Meditz excitedly awaiting the birth of their first child, expected at the end of May. One pleasant April day Mary Jean was sitting on a glider on the front porch of the Meditz’s home on Orville Avenue reading a local newspaper, The Kansan. One article announced the men from Kansas City, Kansas who had been drafted into the United States Army. Mary Jean perused the list, seeing if any of her high school classmates were included. She was dumbfounded to see the name of Friedrich Meditz on the list of draftees. The young couple were in disbelief, so much so that the next day Mary Jean called the Kansas City, Kansas draft board. She explained that some mistake had been made because her husband, Friedrich Meditz had not received any notice about being drafted, and she asked if there could be another individual of the exact same name who had been drafted. The Selective Service representative had a terse reply, “oh, you will be hearing from us, don’t worry.” And, sure enough, a couple of days later the notice to report for induction arrived. Friedrich was given a sixty-day delay in his induction because of the impending birth of his child.

On May 28, 1954 Friedrich and Mary Jean Meditz welcomed their first child, Teresa to their young family. Two months later, on July 19, 1954, Friedrich Meditz was inducted into the United States Army.

Fred Meditz sits in front of his tent during maneuvers near Neu-Ulm, Germany while in the U.S. Army, circa 1956.

Friedrich reported to the Kansas City, Kansas induction center and was sent to Fort Bliss, Texas for his basic training which he completed on October 2, 1954. After training, Friedrich was assigned to the 9th U.S. Infantry Division, 47th Regiment, Company K as a light arms infantryman, a rifleman. The 9th Infantry was assigned to the American Occupation Zone in Germany, stationed at New Ulm. Friedrich excelled in the military and was made a Squad Leader while in Germany

Fred and Mary Jean Meditz pose with their daughter, Teresa, in this view from Germany, circa 1955.

On August 16, 1955, Friedrich Meditz was granted full citizenship to the United States from the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service in Munich, Germany, earned by his service to the United States Army. In the naturalization order, he changed his first name to Fred.

This certificate of naturalization was presented to Fred Meditz on August 16, 1955 by the Office of Immigration and Naturalization in Munich, Germany. Notice that it lists Fred’s former nationality as “stateless”.

In the fifteen years which spanned 1941 through 1955, Fred had been a citizen of four different nations, served in two armies on opposing sides, spent five years in a refugee camp, and immigrated alone to a nation where he could not speak the native tongue after living in the Third Reich for the duration of the war. Despite that decade-and-a-half odyssey, by the end of 1955 Fred was an American citizen, living in Kansas City, Kansas in his own home with a wife and daughter.

Fred Meditz, second from left, relaxes with other soldiers, enjoying a Coca-Cola at the Army camp at Neu-Ulm Germany, circa 1954-1956. Notice that the third soldier from the left is a member of the West German army. Fred frequently acted as an interpreter for the military.

In September of 1955, Mary Jean and Teresa returned to the Meditz home in Kansas City, Kansas. Nine months later, Fred returned from his tour of duty in Germany aboard the U.S.N.S. Geiger, and on June 7, 1956, Fred received his separation in service from the Army, having spent seventeen months overseas. He was not, however, discharged from the Army, but was required to be a member of the Army reserves for an additional six years to fulfill his eight-year commitment to the military that was required of draftees in the 1950s. On July 18, 1962 Fred received an honorable discharge from the United States Army.

Fred and Mary Jean had a second daughter, Cheryl, born in 1959, the same year that Fred built the family their first new home in Shawnee, Kansas. Six years later, Fred built a new house in Merriam, Kansas which became the Meditz home for the next fifty-two years.

Click on any image below to view in a gallery format or as a full-screen image:

Categories: Family Stories, Uncategorized, war stories

Toller Artikel. Vielen Dank.

LikeLike

Vielen Dank für den tollen Artikel.

LikeLike

Toller Artikel…

LikeLike

Interessanter Artikel.

LikeLike

My mother lived the same experience and may even have met Fred in Rann. Great information and well told. Thank you

LikeLike