V: Interventions and Appeasement

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

The Red West and the Stirring Bear: 1920 - 1937

“The Weltkrieg slew an entire generation of men. It starved women and children to death in the homes and streets of the Reich. Speaking to those that suffered this did not relish reliving that hell. Victory did what no defeat could. It quenched the old warrior spirit of Germany – that Prussian bloodthirst. Yes, it lingered weakly in the hearts of some aristocrats and military officers. Yes, there were the old slogans and signs triumphing German arms. But in the hearts of the Volk it was absent. Germans now dedicated themselves to ruling their colonies, to writing poetry and literature, to scientific discoveries, commerce and above all, to life.

Was it no wonder then that when the red horseman of war reared his head that all was done to reassure him to lower it? Was it a fault to want no more of the glimpse into the evil that lay beyond fragile human civility? Were the men and women of those age so wrong to remember their own suffering and not wish it upon their children? People would fight for their families, for defense of the Fatherland, but for glory? No. They had seen the face of modern war. It was not beautiful. It was hideous.”

– Walberga Sommer,

Friedensoldaten, Frankfurt: FES, 1993. Passage written defending the Policy of Placation, which was often denigrated in later decades

German graves close to the battlefield near Reims

Many mistake the Third Internationale powers, especially the French, for going into the Second Weltkrieg with revanchist ambitions. This was certainly not as true as it was with Russia. Instead, France and to a lesser extent the Union of Britain and the Socialist Republic of Italy, saw themselves as the harbingers and champions of syndicalist ideology. It was recognized by many that it couldn’t be enough simply to achieve syndicalism in their own countries. Any success they achieved in implementing their economic model would threaten bourgeoisie and monarchists the world over. Certainly Germany, the prime capitalist country of the world, would not abide successful syndicalism on their borders. To do so would prime its own people for revolution. Germany would go to war before allowing this to happen.

With their futures hampered by the forces of reaction, if not in war, then by policy, something had to be done. Moreover, many syndicalists saw it as their humanitarian mission to free people across the globe from capitalist tyranny. The inevitable German counter itself had to be countered. Thus, knowing peace was impossible, the member nations of the syndicalist alliance, the Third Internationale, undertook to foster the consciousness of class struggle and syndicalist thought globally via a far-flung network of agents, informers, activists, artists and more. The mythic mission of the Third Internationale was world revolution. A final war would give way to peace, prosperity, and the evolution of humanity into a more perfect utopian society.

British Syndicalist propaganda posters from 1929 and 1941 respectively *

During the Twenties, the syndicalist governments of the British and French had largely kept to themselves, spending their energies on internal stabilization and self-discovery. Germany, lulled into a false sense of security by its ‘golden era’, had ignored and denigrated the new syndicalist governments, even seeing them as weak enough as to not pose a danger if normal trade relations were resumed. As the Thirties emerged however, the syndicalists, with their self-preserving mission for world revolution synchronized, entered the world stage as emboldened powers.

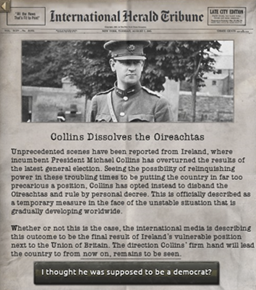

After their period of consolidation, the new red regimes of western Europe looked to begin to put into place their mythic goal. They intervened in the Dominion-Bharatiya Crisis in 1925-26, supported the survival of the Left Kuomintang government in southern China in 1933, the Patagonians in the Argentinian Civil War, helped instigate the Norwegian Revolution of 1936 and openly supported the Indochinese rebellion and the Socialists in America. Their proxies operated in worlds across the country, from the Kingdom of Ukraine and the Netherlands to Australasia and Mittelafrika.

When German weakness became apparent halfway through the decade both powers sought to accelerate the overthrow of European hegemon through internal sedition and revolution. The attempts failed when Germany, sensing this danger, banned socialist organizations with ties to the Third Internationale (and later all French organizations, which the French named as cultural war). Coupled with the new Lettow-Vorbeck government’s partially successful economic recovery program and constitutional reforms, the seething discontent in Germany somewhat receded (though not entirely as the later Rhineland occupation was to show). Nonetheless, the superpower had been humbled. While Germany looking inward there was a golden opportunity at hand; if ever there was a time to bring syndicalism to the oppressed masses of the world it was now. It may not be into Germany itself, but if the Reich could be surrounded by an alliance of likeminded nations, if its basis for imposing its imperialist ambitions worldwide could be curtailed or blocked, then perhaps world revolution could be achieved within their generation.

The other great specter of German dominance was its old rival in the east, Russia. Elected in 1934, Boris Savinkov and his political party, the Union for the Defense of the Motherland and Freedom (SZRS), came to power with reclamation of Russia’s greatness as the core of their platform. To them, this meant reestablishing Russian hegemony across its former territories, up to and including the ones stripped from them in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Bloody vengeance and cold, geostrategic calculation was Russia’s game. An ultimate war with Germany, whether to fully conquer it or to break its back in the east, was discussed from the days even before Savinkov’s ascension.

Russia in 1933 was nearly as weak as it had been through the Twenties, and so Savinkov instituted major reforms centralizing as much power on himself as possible. By 1937, Savinkov had long since purged rivals to his power and had proclaimed himself the ‘Vozhd’, or the ‘Leader’. By this time, the only institution that might still threaten him was Army High Command (Stavka) and its officers, though their interests thus far had aligned. The SZRS had also implemented massive industrialization across Russia to help strengthen the nation’s war making ability (the Vokshod ‘Sunrise’ program) and insulated their economy from the German one via various other policies.

As with the Third Internationale, the Russian State also saw Black Monday as its opportunity to begin applying its long-term designs. The Russian military, hesitant that its strength was not yet fully able to confront the Germans and that its new doctrines were largely untested, acted to slow the Vozhd’s plan. By 1937 however, Savinkov had maneuvered the situation in Russia as to make it impossible for his generals to keep the plodding attitude. Russia had begun to move.

Savinkov attempted to institute a cult of personality across Russia **

Artwork celebrating the creation of an official ‘Vozhd’ office, possible after the Chernov Purge saw the dictator’s last political enemies exiled or assassinated ***

The Restive Pole: April, 1937

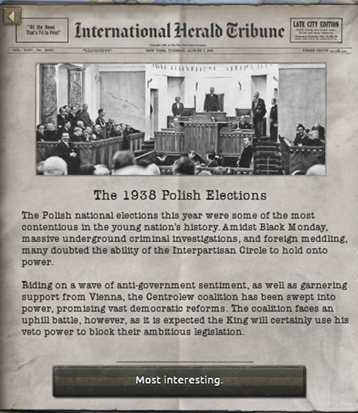

The international quandaries of 1937 began with the Great Peasant Uprising in Poland. Unemployment had risen precipitously in Poland as it had across all Mitteleuropa due to the Black Monday economic depression. Joblessness combined with other stresses rocking the Polish peoples. From Moscow came fire-and-brimstone pamphlets from exiled Poles adopted by Savinkov’s regime, such as Roman Dmowski. These were widely distributed in churches, slums and at town halls across the small country and called for nationalist uprisings and alignment with Russia. The Oboz Zjednoczenia Narodowego (OZN) party, also funded by Moscow-affiliates, also captured the hearts much of the conservative intelligentsia and the veterans. Often, OZN troops would clash with Polish gendarmes, pro-syndicalist marchers and even Jews, whom they wished to expel from the country. The figure that both syndicalists and nationalists could both hate was Poland’s king, a son of Wilhelm II; August IV of Poland. The embers within Poland were stoked from all sides, eventually threatening to come together in a conflagration.

King August IV Hohenzollern of the Kingdom of Poland

In April the various nationalist factions declared a strike, demanding the exile of the Royal Government, the end of Dmowski’s exile and the release of political prisoners. Polish syndicalists soon joined in, insisting on land reform and welfare. There were bloody clashes in the streets of many Polish cities, leading a panicked King August to telephone his father via the German embassy to ask for aide. Wilhelm, always somewhat disgusted with his ‘weakling’ son, declined to answer the phone himself and instead patched him through to the Foreign Minister. The response was to simply to break up the rioters. August, thinking he had the backing of Germany, ordered a maximal response. The army was called out and tens of thousands of protestors were arrested.

Threats of war from both the French and especially the Russians followed. Furious over the treatment of ‘oppressed peoples’ (at least that is, the ones aligned to their worldview and not a few of their agents), the Polish government soon released most of the prisoners, keeping only the ringleaders. The German Foreign Office and General Staff, in discussion with Lettow-Vorbeck about the potential growing prospects of war, indicated to him that the German military was certainly not ready for a two-front war as well as a full-on uprising in Poland – not with Indochina in flames, Mittelafrika in tatters and the military still reeling from its budget cuts.

Radicalized Polish peasants flooded into the cities to protest

On behalf of August, Lettow-Vorbeck negotiated with the Russians and French, securing the release of all but the most virulent of the strikers. It was another tally in the column of perceived German infirmity, though for those who lost family members in the clashes between rioters and police it would have seemed anything but. There were many who would not forget what was done that cloudy April.

This incident began what is now recognized as the Politik der Beschwichtigung (the Policy of Placation), which would be developed more throughout the string of international incidents in 1937-38. The Policy would in later years be one of the most maligned strategies of the Lettow-Vorbeck government, being accused as one of the central pillars that helped lead to the Second Weltkrieg.

The Annecy Conference: April 1937

During the short French Civil War that followed the Weltkrieg, loyalist Republican forces used the mountains of the Haute-Savoie region to hold out against the Communards for months. The forming Commune was alternately ruled by many different factions of syndicalists, each with their own vision for how to run the country. At the time of the Haute-Savoie beleaguerment, it was the radical Jacobins, with much of their ideology derived from the Russian Bolsheviks, who guided the path of the Commune (though they were overthrown by the resurgent Sorelians in 1921). Paranoid about the Jacobin vision of spreading world revolution immediately, the Swiss made a calculated and cynical decision to invade Haute-Savoie.

Taken in the rear by complete surprise, the Republican forces quickly surrendered to the Swiss, who established the region as a buffer against the Commune of France. Despite French indignity, the Swiss remained in the occupied region. Germany declared its backing for Switzerland in the issue and thus there was little that France, bloodied, war-weary and still ideologically unstable could do.

Swiss alpinist troops observing the French border

For the next seventeen years Switzerland continued to occupy the region, which acted as a pressure valve for many discontented elements in French society. Despite repeated French requests for the province back, the Swiss government refused to even enter negotiations as they had never recognized the Commune government.

At last, however, in May 1937, the Communard parliament, the

Bourse Générale du Travail, authorized the issuance of an ultimatum. With Germany distracted by economic and foreign chaos, the time to right the wrong of 1920 had come. On May 1st, the Premier of the executive branch of the Commune’s government, Léon Jouhaux, announced on the radio that he was providing the Swiss government one week to comply with the handing over of Haute-Savoie, citing persecution of the French populations there. French military units were seen being rushed to the area as well as to the German border. Within a week the British had reinforced the Franco-German border with another ten divisions as well, demonstrating their aptitude for logistics and deployment.

Unionist troops riding tankettes toward the Franco-Flanders-Wallonian border

The dropping of negotiation for a demand backed by military threat sent shockwaves through both Bern and Berlin. Having repositioned several military units east to deal with the sudden change in the Reichspakt security order due to the collapse of the Baltic Duchy and to sternly warn the Russians about moving westward, Germany was unprepared for war. She was not mobilized, nor had much equipment been modernized or repaired in the last two years.

The Chancellor was against giving into French demands, stating that “

Territories are not toys, nor nations toddlers. You cannot just give in when one tantrums. If the Swiss recognize the Commune then perhaps negotiations can resume.” The populace, however, was largely against war, Foreign Secretary Albert Dufour-Feronce argued. Many others, including Hjalmar Schact, still chairman of the NLP, agreed. “

Why then, would we fight a war on behalf of a nation who indeed stole this territory nearly two decades ago?” Schact posed. The nation remembered the Weltkrieg and didn’t wish to relive it for some insignificant territorial spat. The idea for a ‘Conference for Peace’ was floated. The Chancellor retorted that to “

simply meet with them [the French] after they make such absurd demands”, for it put the ball of diplomatic momentum in their court. It would set a dangerous precedent that Germany was willing to sacrifice the territorial integrity of its neighbors in order to be left alone. The French still had plenty of lands they claimed were rightfully theirs. Where would the demands end? With Wallonia? With the colonies? With Luxembourg? With Alsace-Lorraine? A heated discussion followed, in which the ministers threatened to resign if the Chancellor did not acquiesce to the proposal of the Conference. Reluctantly, the Lettow-Vorbeck agreed.

Within two days, a conference was arranged between the Chancellor, President Jouhaux and Albert Meyer, President of the Swiss Confederation. The three heads of state traveled to Annecy in the heart of occupied Haute-Savoie where three days of discussions. The first day ended with an impasse. The Chancellor proposed that the French Commune be diplomatically recognized by the Swiss and that a plebiscite should occur to determine Haute-Savoie’s fate. The French refused, reminding the Germans that they themselves had never recognized Haute-Savoie as a fully annexed territory. For the French to allow a plebiscite was to acknowledge that the territory had been (or could be) transferred legally.

L'Imperial Palace, Annecy, where the Conference took place

On the second day negotiations dragged on long into the night. Eventually, Lettow-Vorbeck and Jouhaux excused themselves to a different room to carry on negotiations over brandy and cigars, much to the humiliation of President Meyer. By the third day, a working compromise had been agreed; Haute-Savoie would be transferred back to France within two weeks. In turn France would give assurances of Swiss territorial integrity and accept the German banning of syndicalist organizations on its own territory (renunciation of Flanders-Wallonian territory and Alsace-Lorraine were deemed too complicated to factor into the conversation and were dropped unilaterally by Lettow-Vorbeck during the ‘Midnight Meeting’).

Peace had won. The next day, in a sign of hopefully new Franco-German accord, Jouhaux and Lettow-Vorbeck jointly laid wreaths at a memorial for the Weltkrieg dead of Annecy. President Meyer did not attend. Publicly, he claimed that this was out of protest to being left out of the negotiations. Privately however, it was because there were rumblings that the Swiss Federal Government was to oust him as President to use him as a scape goat.

Lettow-Vorbeck laying his wreath

Despite the hopeful tone of the end of the conference amity was not reach between France and Germany. Nearly as soon as Lettow-Vorbeck had returned to Berlin, new complaints about German mistreatment of French citizens in Nanzig (Nancy) began to be lodged by the French ambassador.

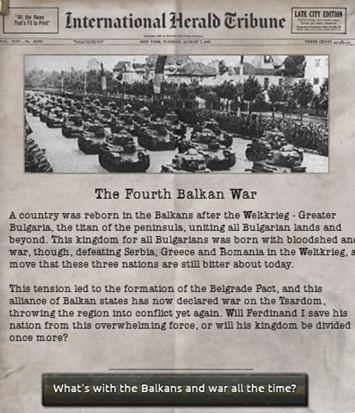

The Bear’s ‘Little Wars’: May - September 1937

The Russian bear, long dormant, had awoken. In 1937, Savinkovist Russia embarked on the first step of its reconquest of the lands that had split off from it during her disastrous civil war. Having brutally crushed a rebellion of the Caucasus Cossacks, the burgeoning Russian military, powered by the SZRS’s industrial programs, turned its sights on Central Asia. With little more excuse than cold geopolitical calculation, the Vozhd gave the order to ‘

bring the Asians back into the fold’.

On April 1st, Operation

Kopytnyy Grom (Hoof Thunder) saw more than forty Russian divisions rolling across the Kazakh steppe. Mixed in amidst these forces were motorized and armored formations equipped with radios and a flexible, aggressive doctrine that took inspiration from the White cavalry of the Russian Civil War (in a similar vein, the Red Russian exile Mikhail Tukhachevsky took similar lessons with him to the French Commune). These formations were held in the overall command of Pyotr Wrangle, the Black Baron, who had helped formulate the aggressive, deep striking principles of the New Russian Army during the Fourth Balkan War.

Pyotr Wrangel, the Black Baron

The leaders of the four targeted states, Madamin Bek (Turkestan Republic), Junaid Khan (Khiva), Mohammad Alim Khan (Bukhara) and Alikhan Bukeikhanov (Alash Orda), met in Tashkent pledging to fight with one another to the end. It was a pledge they did not, or rather, could not hold to, for the Russians moved too quickly.

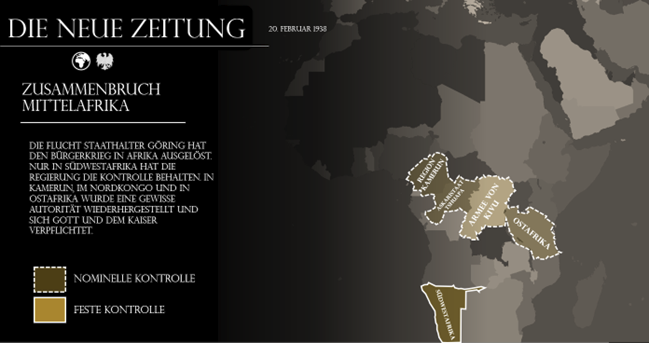

As Russian infantry wheeled eastward toward Lake Balkhash, Wrangel and motorized forces pushed their men down into the Turan Lowlands down into the Khivan Emirate and onto Bukhara. Air power was nearly uncontested as hundreds of Russian fighter planes and close air support blotted out the sun.

By the early autumn 1937 the wars had all but concluded. The Russians crushed Alash Ordan resistance after pinning their best forces against the Altai Mountains and besieging its capital of Nur-Sultan. As Nur-Sultan’s taking proved troublesome, the Russian Chief of the Airforce, Vyacheslav Tkachov, ordered the formation of a heavy bomber group. As a show of force, the ancient city of Bukhara along with much of its glorious and beautiful Islamic architecture was pummeled to the ground, along with thousands of civilians (an event later immortalized in Pablo Picasso’s

Bukhara painting).

Aerial photograph of Bukhara as it burns

Damaged minaret from the Russian bombardment

Surrenders from Khiva and Nur-Sultan followed shortly. The Turkestan Republic lingered on until the end of the year, committing itself to guerilla warfare in the mountains and arid steppe. Nonetheless, its government signed the articles of surrender, essentially liquidating the last of the short-lived Central Asian states.

Russian attack on Karaton, Alash Orda

Russian losses were minimal, numbering some 15,000 – 20,000 total casualties. Enemy losses were far higher. Lacking the western technology in armor and airpower, the Central Asian quartet were crushed, with most of their armies being encircled in the opening months of the war.

The German General Staff, still mired in the Weltkrieg-era mindset of static, defensive warfare, paid little heed to the Russian success in Asia, going so far as to carelessly name that style of warfare ‘impossible’ in a European setting against peer opponents. Other German generals, such as Heinz Guderian, however, had their experimental theories proven correct. With the right combination of armored thrusts, aerial harassing, stormtrooper infantry tactics and artillery curtains, gaps could be opened in enemy lines. By combining two or more of these pinpoint attacks and follow-ups, massive encirclements could be achieved.

Germany’s response to the situation in Central Asia was limp. While Foreign Secretary Albert Dufour-Feronce condemned the attack on ‘neutral and peaceful Scythia’, little was done to curtail the Russians. Savinkov replied to the speech over the radio waves, reminding everyone what Germany had done to “neutral and peaceful Belgium”, using the old name for Flanders-Wallonia. “

Where Germany ventures, Russia will match,” Savinkov concluded.

Within the Foreign Office it was considered more

cost effective in the long run to let the Russians focus their energies on the east rather than on the west. It was even hoped that Russia might try to retake Vladivostok, who which was held by Japanese-backed dissident Admiral Kolchak. Japanese-Russian enmity would be of great benefit to the Reich, who since the Weltkrieg had faced down Japan in the Pacific. Of course, the Russians would turn west one day, but let that be years from now. Despite his initial combative stance against the Commune, the German Chancellor largely agreed with this attitude. However, as 1938 was to prove, events would unfold quicker than expected in Europe.

Though the Central Asian nations were far removed from everyday life, a groundswell of pity began to form within the German populace. Between the ceding of Haute-Savoie and the endless parade of grim news the last few years, a sentiment of themselves being taken advantage of had begun to gestate within some quarters of Germany. It was the first inklings of the wartime spirit that was to soon return.

The American War: March - April 1937

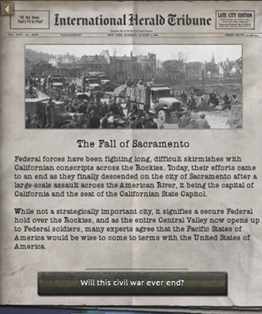

The Second American Civil War flared up quickly after the end of MacArthur’s Thirty Day Moratorium. Militia were called up, National Guard units raised, and battle lines drawn. Even before the start of the conflict, international brigades had been raised and were en route to America. Germany too, joined in on the conflict.

After relocating himself to Denver, the German ambassador Friedrich Wilhelm von Prittwitz und Gaffron had finalized the highly secretive arrangement between the German and American governments for German assistance. Under the guise of “volunteers”, three German divisions under the command of Werner von Blomberg. Along with Heinz Guderian, von Blomberg was a part of the Ölköpfe (Oil Heads), an unofficial clique of military intellectuals advocating for the cutting edge of armed forces doctrine. These elements included tight integration between both air and land units to achieve a new kind of combined arms operation. Cannonades would concentrate on specific points to weaken the enemy. Mobile infantry would quickly ascertain weak points while close air support would be called in by field officers with radio to pilots who could adjust their targets as requested or relay vital information beyond the infantry’s line of sight.

The new doctrine would be formalized over the next several years but its first strains can be seen in the land campaign in America. Upon arriving in Texas unscathed on April 9th without the sighting of even a single enemy ship or airplane, Blomberg addressed his troops, jokingly naming them the “Cowboy Legion” to many cheers and laughs (the name would stick). They consisted of a heavy tank formation, motorized infantry, and a traditional infantry division. Two of the divisional commanders, Major Generals Arthur Schmitz and Hugo Fuchs, were among the Ölköpfe, while the third, Ernst Becker, was sent to essentially watch over Blomberg by the traditionalists at the General Staff.

The “Cowboy Legion” order of battle

There, hastily assembled and expecting to be thrown into battle against the syndicalists, Blomberg also announced shocking news. The Cowboy Legion would not go to fight the Jack Reed’s syndicalists, not yet at least, but instead would be sent west to crush the fomenting Californian uprising. Japan could not be allowed to gain a toehold in America, Blomberg explained. Indeed, the Japanese were supporting the Merriam Clique, having already reportedly sent several divisions of their own to California. To many Germans in the Legion it was a somewhat anticlimactic tone that stank of geopolitics rather than combating the hated Marxist ideology. The main necessity though, the general insisted, was that by clearing the Pacific coast, the Federals could acquire the necessary resources for a prolonged war if indeed it came to that.

And so, on that uncertain spring, the German international forces joined the fray, soon to make history.

* This artwork is from Kaisercat Cinema

** This artwork is from u/parnjt26 – sourced from

Reddit

*** This artwork is from u/Lord910 – sourced from

Reddit