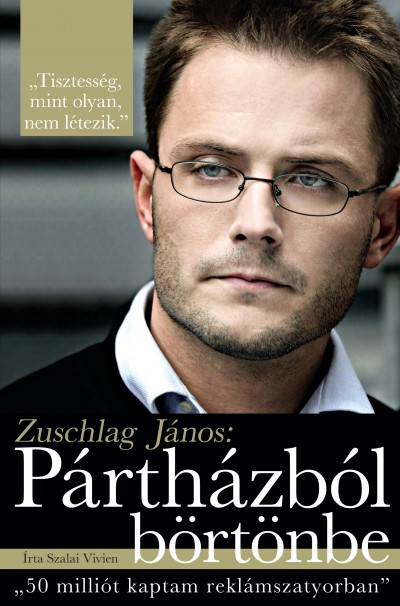

János Zuschlag was only 21 years old when he became a Member of Parliament for the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) in 1998 and the country’s youngest MP. Nine years later, he was charged with fraud and received an eight year prison sentence. He spent six years behind bars, before being released in 2013. In the middle of the 2014 national election campaign, Századvég, a publishing company and think tank closely associated with the governing Fidesz party, published a tell-all, gritty and partially tabloid-style book with Mr. Zuschlag, focusing on his meteoric rise to power at such a young age, corruption within the previous MSZP government and the demise of his own political career. The timing of the book’s appearance during an election campaign–which Mr. Zuschlag compiled with Vivien Szalai, a journalist with a tabloid paper called Bors, who has since become news director at TV2–was obviously no coincidence. It was meant to cause maximum damage to the Socialists.

I purchased a copy of From Party Headquarters to Prison shortly after it appeared, but I had put off publishing a review for a number of reasons; first and foremost because after an initial read, I found it so thin on policy discussion and meaningful insight into the political narratives of the day, that I really did not know where to place it. I had little interest in reviewing a piece of sensationalist tabloid journalism. More recently, I took a second stab at the book and realized where it provided some value. From Party Headquarters to Prison explores and encapsulates the vacuousness and superficiality of Hungarian politics–or at least so much of what goes on behind the scenes. So often, politics in Hungary is devoid of politicians with actual convictions of any kind, references to ideology serve merely as window-dressing, meaningful policy debates are rare, personal favours are rampant, and the country’s political discourse is led by politicians who see their respective political parties as little more than employers, their positions as nothing more than a means to an income and their main priority as appearing as loyal and as servile as possible to the people who hold the purse strings. People often rise to the top of their political career at a remarkably young age in Hungary, but then face a crisis later in life, when their world crumbles.

In some ways, this is the story of János Zuschlag. Yet the fact that he was convicted and sentenced to a stiff eight years in prison, of which he served six years, for having embezzled 75 million forints (approximately $350,000), makes him a rare case. Corruption in Hungary almost never carries any consequences–and thus far, absolutely nobody from the currently ruling Fidesz party has been held accountable for systemic and blatant instances of corruption. Mr. Zuschlag believes that he served as a type of sacrificial lamb or a fall guy for the Socialists and that he was “shamefully abandoned” by his own party.

János Zuschlag: From Party Headquarters to Prison. (Budapest: Napi Gazdaság Kiadó Kft., 2014) 220 pgs.

János Zuschlag describes himself, especially how he was as a teenager and then a young adult, as having been fiercely ambitious, ruthlessly competitive, as well as brash. He offers a scathing opinion of former Socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány, yet the two men share some of these same characteristics. Additionally, both come from similarly modest, small-town or rural backgrounds.

Mr. Zuschlag was raised in the town of Kiskunhalas (population 28,000), some 148 km south of Budapest and near the border with Serbia. He speaks kindly of his hard-working parents, even though the very modest existence that they were able to secure for their children was the source of what Mr. Zuschlag admits turned out to be an inferiority complex that followed him through his youth and much of his political career. When he would throw fits, his mother would lovingly and patiently try to calm him down, with what Mr. Zuschlag described as her “cold and rough hands, the hands of a true worker, which managed to sooth me.”

“My mother and father worked hard their whole lives and for what? So that from a one-room, oil-heated rental apartment, where four of us lived, we could move into a tiny house? This was their life’s accomplishment,” reflected Mr. Zuschlag. “If I committed any sins as a child, it was that I could not bear to accept being vulnerable and I dreaded a future where I would rot in Kiskunhalas, let’s say as a manual labourer, with mundane worries, sitting on the ruins of a hopeless life,” he added.

Growing up, the young János Zuschlag was a loner–he had few friends in school, he was looked down upon by those who came from more affluent backgrounds and he was considered to be a largely out-of-control young man, with little respect for authority. Mr. Zuschlag argues that one of the major failings of Hungary’s system of public education is that it exacerbates socio-economic differences among Hungarian children. “The school system brings to the surface these differences. Children from poor backgrounds cannot go on field trips abroad with their peers, they cannot dress appropriately for school and they cannot buy anything from the school cafeteria or canteen. They are entitled to nothing,” notes Mr. Zuschlag.

One of the recurring themes in the first part of the book is the trauma of never having any money to buy anything at his school’s canteen, while the classmates around him were able to purchase bags of chips, chocolate bars or sandwiches. Mr. Zuschlag was 14 years old, when he first stepped foot into a theatre. He was milling around the snack bar, envious of his peers who were able to purchase treats. He eyed an attractive 15 year old girl, with her friends, but forgot that his mother had given him a garlic sandwich, which was reeking in the pocket of his pants.

“Good God, it’s Zuschlag who smells like this!”–noted one of the girls, before adding: “What’s wong, are you hiding food in your pants, you poor slob? Didn’t they teach you that it’s inappropriate to bring packaged sandwiches into a theatre?”

The young János was mortified and this incident apparently solidified his resolve to climb the social ladder as rapidly as possible.

On some occasions, Mr. Zuschlag took his fate into his own hands, to get what he wanted, at nearly all costs. He recounts how he always wanted to try a Snickers chocolate bar, which first appeared in Hungary during the early nineties. He did not have any money for one, so he shoplifted the chocolate from a local grocery store. When he was confronted by the store clerks who saw him pocket the item, he ran away with him. The next morning the whole community was talking about the incident and it was source of deep embarrassment for his parents and his grandmother. He tried to console his grandmother, by promising her that one day he would become a great man.

“Don’t be great, just be decent. That already carries with it human greatness,” she responded.

*

As a teenager, János Zuschlag was gradually introduced to the world of politics, primarily through two local men who were involved in their respective parties. One of them was the local museum director, who was also a Fidesz representative. He took the young János on field trips, introducing him to archaeological sites. The two had many political discussions, although Mr. Zuschlag noted that already at this young age, he gravitated to the left. He was also an avid reader of the left-centre Népszabadság daily, devouring political news.

A more significant relationship for the teenager was the time he spent with the President of the local Hungarian Socialist Party association in Kiskunhalas, József Venczel. Mr. Venczel convinced Mr. Zuschlag to join the party in 1994 and according to the book, he was the one to introduce the young man to left-wing ideology. Following high school graduation, Mr. Zuschlag moved to Budapest, where he began post-secondary studies in history. Not having enough money to rent an apartment, Mr. Zuschlag lived in a dormitory. In fact, he continued to live in the same university residence when he became az MSZP MP–having entered parliament through the party list–after the 1998 elections.

The first recollection of being a newbie Socialist MP was that of sexual assault, at the hands of a male parliamentarian. Mr. Zuschlag was in an elevator, in parliament, when the older MP demanded sexual favours from the 21 year old newbie. Mr. Zuschlag pretended that it was just a joke, then awkwardly changed the subject to work-related matters and to the subject of fashionable neckties. The older MP would have none of it. He pressed the emergency “stop” button on the elevator, attacked Mr. Zuschlag, groping and fondling him. The young MP was able to break away and re-started the elevator. “I literally fled, as soon as the doors opened. But he yelled after me: ‘it’s going to happen sooner or later!'”

Another disturbing moment for Mr. Zuschlag, barely two years into his first term, was that he was apparently being monitored, during a power struggle and brewing corruption scandal within the Hungarian police. Mr. Zuschlag stood by the embattled local police chief from his hometown, which apparently raised eyebrows–so much so, that he ended up being monitored. “Zuschlag, I want you to come see me tomorrow. Of course, I don’t want to disturb you while you’re on the treadmill in that nice 15th District gym”–said Péter Gergényi, a police captain, over the phone. That is when it dawned on Mr. Zuschlag that he was being followed. The remainder of the discussion was even more bizarre, with a policeman effectively ordering around an MP. When Mr. Zuschlag said that he would try to make it in, Mr. Gergényi apparently responded: “I did not ask you to try. I asked you to report.”

**

Two years into his tenure as MP, Mr. Zuschlag had saved enough money to buy an 82 sq. meter apartment in the 15th District and a FIAT. The apartment was in a working class neighbourhood, with Mr. Zuschlag noting: “I felt good among the proletariat.”

The story, however, which speaks volumes about the state of Hungarian politics involves a party in rural Hungary, which Mr. Zuschlag attended during his first term. After a night of heavy drinking (mainly pálinka), Mr. Zuschlag was approached by another guest–an aspiring actress or model, who was known to sleep with politicians, in order to advance her career. She approached Mr. Zuschlag, who invited her for a drink.

“There’s this role…Can you arrange it for me?”–she asked the young MP, hoping that he could pull some strings and land her a gig. She took him into a washroom and performed oral sex on the politician. “I’ll see what I can do for you,” replied Mr. Zuschlag, knowing that there wasn’t much hope.

He then got into his car, heavily intoxicated, and drove at speeds of 170 km per hour. When a police cruiser turned on its lights, instructing Mr. Zuschlag to pull over, he kept driving. Mr. Zuschlag lost control of the vehicle and went off the pavement, as he hit the breaks. When the police caught up with him, he explained that his name is János Zuschlag and that he is an MP.

“Actually, we think that you are a drunk pig!”–responded the officer. Mr. Zuschlag then flashed his parliamentary ID and the officers immediately changed their tune:

“Have a safe trip, Mr. Zuschlag,” they said.

That night encapsulates so much of how Hungarian politics operate–not only the petty corruption, but much more so the sense of vulnerability that ordinary citizens find themselves in and how they view loyalty and favours to those in power as a means to change their own personal fate for the better.

Part two of my review of Mr. Zuschlag’s book will appear tomorrow.