After the Turn ACOUSTIC PATHWAYS

artstyle.international Volume 13 | Issue 13 | March 2024

Cover image © Jörg U. Lensing, Acoustic Pathways: After the Turn, 2024

Academic Editors

DesignbyArtStyleCommunication& Editions

Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director

Christiane Wagner

Senior Editor

Martina Sauer

Co-Editor

Jörg U. Lensing

Associate Editors

Laurence Larochelle

Katarina Andjelkovic

Natasha Marzliak

Tobias Held

Collaborators

Denise Meyer

Marjorie Lambert

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine

editorial@artstyle.international

+1 347 352 8564 New York

+55 11 3230 6423 São Paulo

The magazine is a product of Art Style Communication & Editions. Founded in 1995, the Art Style Company operates worldwide in the fields of design, architecture, communication, arts, aesthetics, and culture.

ISSN 2596-1810 (online)

ISSN 2596-1802 (print)

Theodor Herzi, 49 | 05014 020 São Paulo, SP | CNPJ 00.445.976/0001-78

Christiane Wagner is the lead designer, editor, and registered journalist in charge: MTB 0073952/SP

© 1995 Art Style Communication & Editions

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine is an open access, biannual, and peer–reviewed online magazine that aims to bundle cultural diversity. All values of cultures are shown in their varieties of art. Beyond the importance of the medium, form, and context in which art takes its characteristics, we also consider the significance of sociocultural and market influence. Thus, there are different forms of visual expression and perception through the media and environment. The images relate to the cultural changes and their time-space significance the spirit of the time. Hence, it is not only about the image itself and its description but rather its effects on culture, in which reciprocity is involved. For example, a variety of visual narratives like movies, TV shows, videos, performances, media, digital arts, visual technologies and video game as part of the video’s story, communications design, and also, drawing, painting, photography, dance, theater, literature, sculpture, architecture and design are discussed in their visual significance as well as in synchronization with music in daily interactions. Moreover, this magazine handles images and sounds concerning the meaning in culture due to the influence of ideologies, trends, or functions for informational purposes as forms of communication beyond the significance of art and its issues related to the socio-cultural and political context. However, the significance of art and all kinds of aesthetic experiences represent a transformation for our nature as human beings. In general, questions concerning the meaning of art are frequently linked to the process of perception and imagination. This process can be understood as an aesthetic experience in art, media, and fields such as motion pictures, music, and many other creative works and events that contribute to one’s knowledge, opinions, or skills. Accordingly, examining the digital technologies, motion picture, sound recording, broadcasting industries, and its social impact, Art Style Magazine focuses on the myriad meanings of art to become aware of their effects on culture as well as their communication dynamics.

Content Editorial

Christiane Wagner

Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director

Introduction

Christiane Wagner

Editor-in-Chief

Jörg U. Lensing Co-editor for this special edition

Essays and Articles

Foreword Immersive, Emmersive by Michel Chion

Soundscape: Selected Historical and Aesthetic Perspectives by Sabine Breitsameter

Inspired by Nature: How Acoustic Ecology Influences the Work of Sound Scenographers by Ramon De Marco and Jascha Ivan Dormann

Acoustic Architecture Progressing Beyond Sound Branding: Why Imprint When We Can Craft Together? by Lars Ohlendorf

Acoustic Lanes and Auditory Leads: SpatioTemporalities of Social Acoustics and Public Address Systems in Late Weimar Germany by Heiner Stahl

On the History and Aesthetics of Noise Reduction by Jens Schröter

The Critique of Power Dynamics Through Sound by Gregory Blair

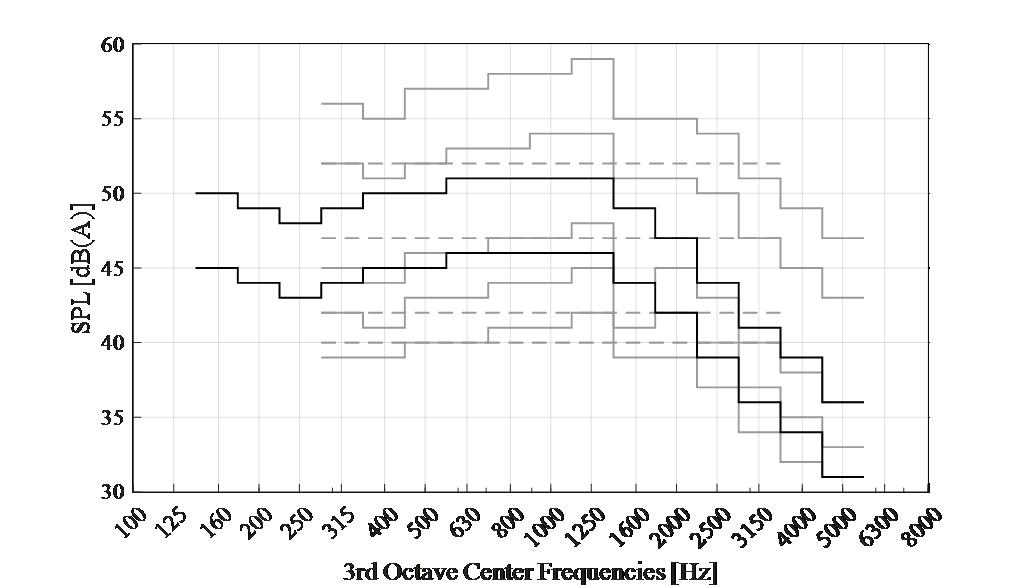

Sound Design for Electric Vehicles: Fulfilling Laws and Creating Digital Artwork by Alessandro Fortino

51 71 85 117 101

11 17 37

129

145

173

Voice in the Machine: AI Voice Cloning in Film by Ross Adrian Williams

Electronic Music: Utopias and Realities by Thomas Neuhaus

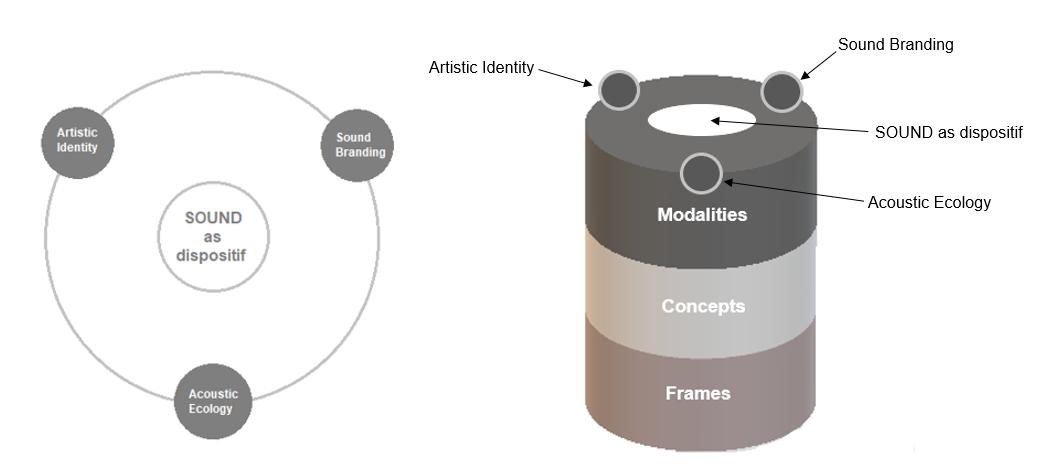

Listen Up! Strategies of Theatre Sound Towards Artistic Identity, Sonic Branding, and Acoustic Ecology by David Roesner

191

203

229

The Audiovisual Chord: Invitation to a Dance Between Sound and Image by Martine Huvenne

Soundesign in German Movies by Jörg U. Lensing

Afterword

The Beginning and the End of the Radio Play by Andreas Ammer

239

Scientific Committee Editorial Board & Information

Editorial

Welcome to the latest release of Art Style Magazine! Our online magazine has come a long way in meeting scholarly journal standards and producing high-quality work. As a result, we have been recognized by several prestigious indexes, including the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), the Web of Science Core Collection, the Emerging Sources Citation IndexTM (ESCI), the European Reference Index for the Humanities and Social Sciences (ERIH PLUS), and Latindex, which demonstrate the editorial team’s strong commitment to maintaining excellence, and more. Our editions cover contemporary themes and are of interest to academics and individuals from various fields. The success of Art Style Magazine is due not only to its editions and editorial team but mainly to the esteemed professors, academics, and authors who share the magazine’s unwavering commitment to providing exceptional content and knowledge that leads to outstanding achievements.

Therefore, this publication on “Acoustic Pathways: After the Turn” is a culmination of extensive research and expert insights from renowned researchers, professors, and specialists in the field. Jörg U. Lensing, a sound design professor at Dortmund University of Applied Sciences and Arts and a director and composer for both theatre and film, has curated this special edition. The aim is to provide a comprehensive overview of this appealing topic. To that end, Professor Lensing and I have edited this valuable publication that offers a deep understanding of acoustic pathways and their relevance in the contemporary world. The sound world has undergone a tremendous transformation over the past few decades. With the advent of new technologies and the rise of digital music, the way we consume, create, and experience audio has changed forever. However, amidst all the changes, one thing remains constant the power of sound to move us, inspire us, and connect us to something deeper than ourselves. When it comes to the world of audio-visual content, the concept of acoustic pathways is crucial. Essentially, acoustic pathways refer to how sound travels through a given space. That can include everything from the physical properties of the space such as the size and shape of the room to the materials used to construct it. From a creative standpoint, understanding acoustic pathways is essential for anyone in audio-visual production. Thus, in this new era of sound design, acoustic pathways have become more critical than ever. As we move away from traditional recording and performance techniques, the need for authentic sound has become increasingly important. Acoustic pathways are the channels through which sound and timbre music flow, connecting the artist and the listener intimately and profoundly What happened after the “acoustic turn” was announced in 2008? Hence, I am thrilled to announce that Art Style Magazine’s latest special edition on “Acoustic Pathways: After the Turn” is a significant outcome, featuring rich content compiled by renowned expert Professor Lensing.

Enjoy this valuable publication, and happy reading!

Christiane Wagner Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 7

Acoustic Pathways: After the Turn

The interdisciplinary anthology called Acoustic Turn by Petra Maria Meyer was published in 2008, and gained attention for a sensory branch that was underestimated until then. Since then, the topics related to sound design have expanded, and it is well-known that wellthought-out sound designs lead to higher quality media and multisensory perception in elaborate radio plays, films, scenography, e-mobility, podcasts, and immersive audio-visual forms of design. Acoustic studies have emerged as a scientific field that combines musicology and media studies. Recent publications such as Handbuch Sound (Morat and Ziemer 2018), Handbuch der Filmmusik (Kloppenburg 2012), and books on sound design have significantly expanded the discourse in the German-speaking world. Additionally, translations of essential works by Michel Chion, such as Audio-Vision (1990 in French, 1993 in English, 2018 in German), have contributed to the growth of this field. Internationally, numerous publications on the topics mentioned below have become standard works.

This special issue on “Acoustic Pathways: After the Turn” comprises original contributions that focus on this subject, along with a foreword by Michel Chion. This French film theorist and composer of experimental music discusses the recent trend in France of using the terms “immersive” and “experience” about certain works of art. He questions the value of these experiences, arguing that everyday life is already immersive and that the term emersive would be more appropriate to describe works of art that present themselves in a structured form, such as music. Chion believes this structure creates the conditions for an “emergence,” or event, that is unique to the listener’s experience.

Further, in “Soundscape: Selected Historical and Aesthetic Perspectives,” Sabine Breitsameter explores the neologism “soundscape” which refers to the sounds we hear around us. This concept has been popular since the late 1970s. It encourages people to focus on the sounds they hear and look at the world from a new perspective. This article explains why the soundscape is important, how it relates to society and the environment, and how it has been studied since the 1970s.

Following that issue, the article titled “Inspired by Nature: How Acoustic Ecology Influences the Work of Sound Scenographers,” by Ramon De Marco and Jascha Ivan Dormann, highlights how soundscapes can affect our emotional response to different spaces The authors have extensive experience in sound scenography and have created audio environments for various settings for Idee und Klang Audio Design. Acoustic ecology plays a vital role in their work and has significantly influenced their approach to sound scenography. In their article, De Marco and Dormann demonstrate the connection between human behavior, species extinction, and acoustic ecology. They also explore the positive impact of acoustic ecology on both non-human species and the environment.

Further, while advanced technologies like AI offer new possibilities for sound branding, in “Acoustic Architecture Progressing Beyond Sound Branding: Why Imprint When We Can Craft Together?” Lars Ohlendorf explores acoustic architecture’s implications in transforming how brands communicate. He explains that exciting possibilities for unique soundscapes beyond physical and virtual realms exist through data and technology, with an emphasis on participation.

8 Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine

Looking back, Heiner Stahl wrote an article called “Acoustic Lanes and Auditory Leads: Spatio-Temporalities of Social Acoustics and Public Address Systems in Late Weimar Germany.” In this article, he discusses a compositional approach to space and time that involves measuring and notating sound in soundscape studies. The article explores the social acoustics of sound and noise in Interwar Germany, and how the management of acoustics was conducted as a political affair. Stahl’s idea of social acoustics is shaped by the interconnectedness of behavior, self-convergence, and technologies.

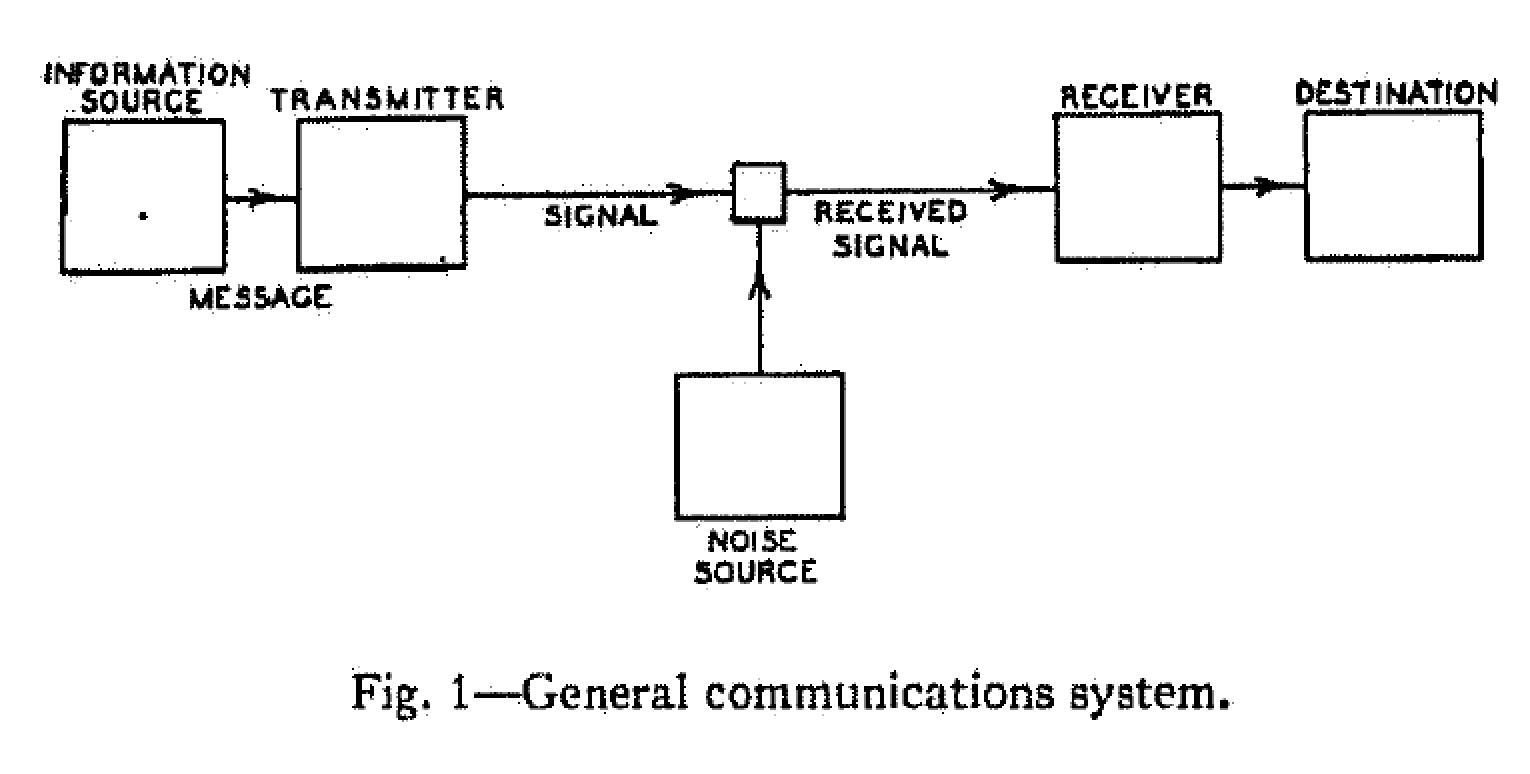

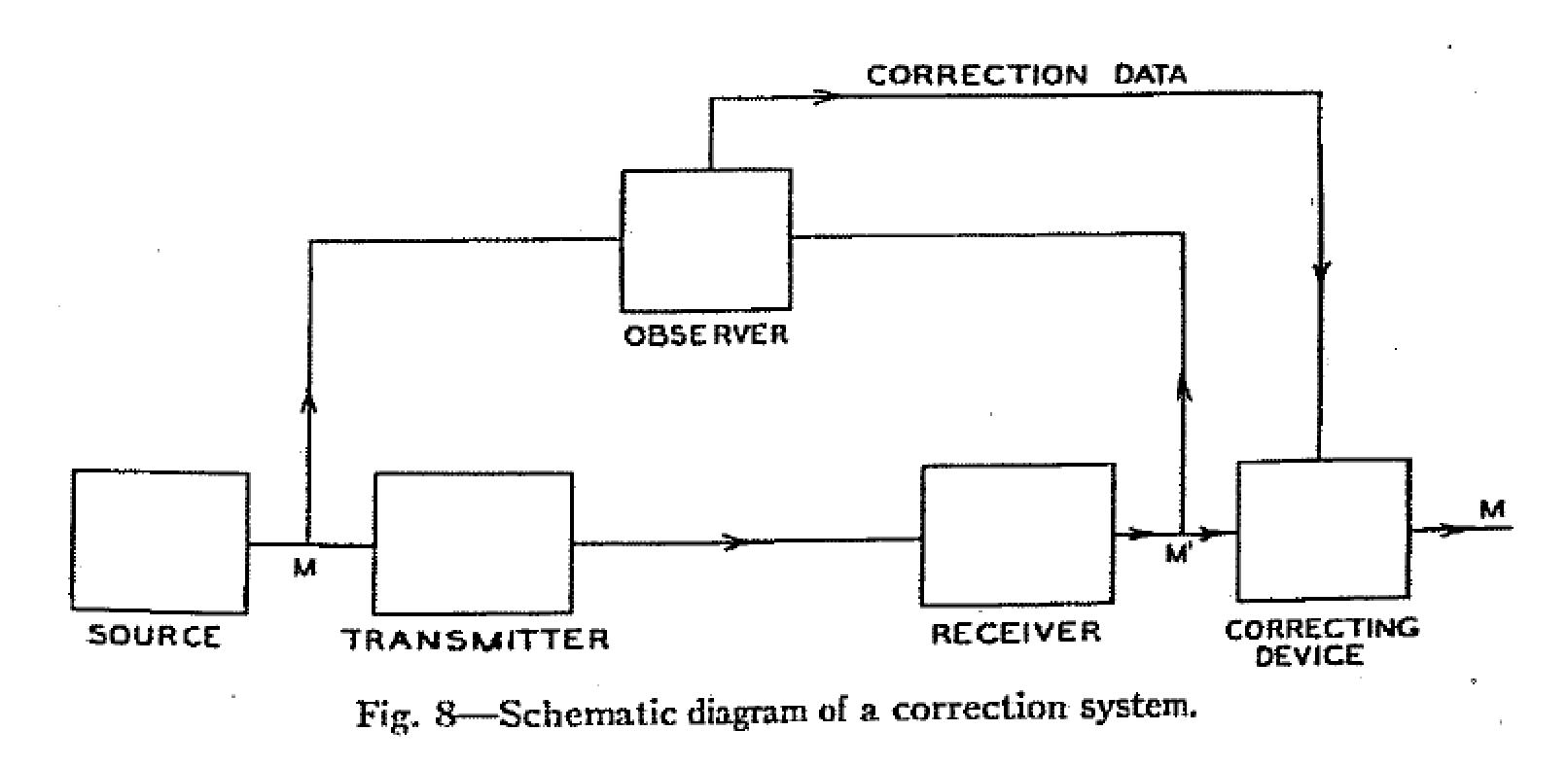

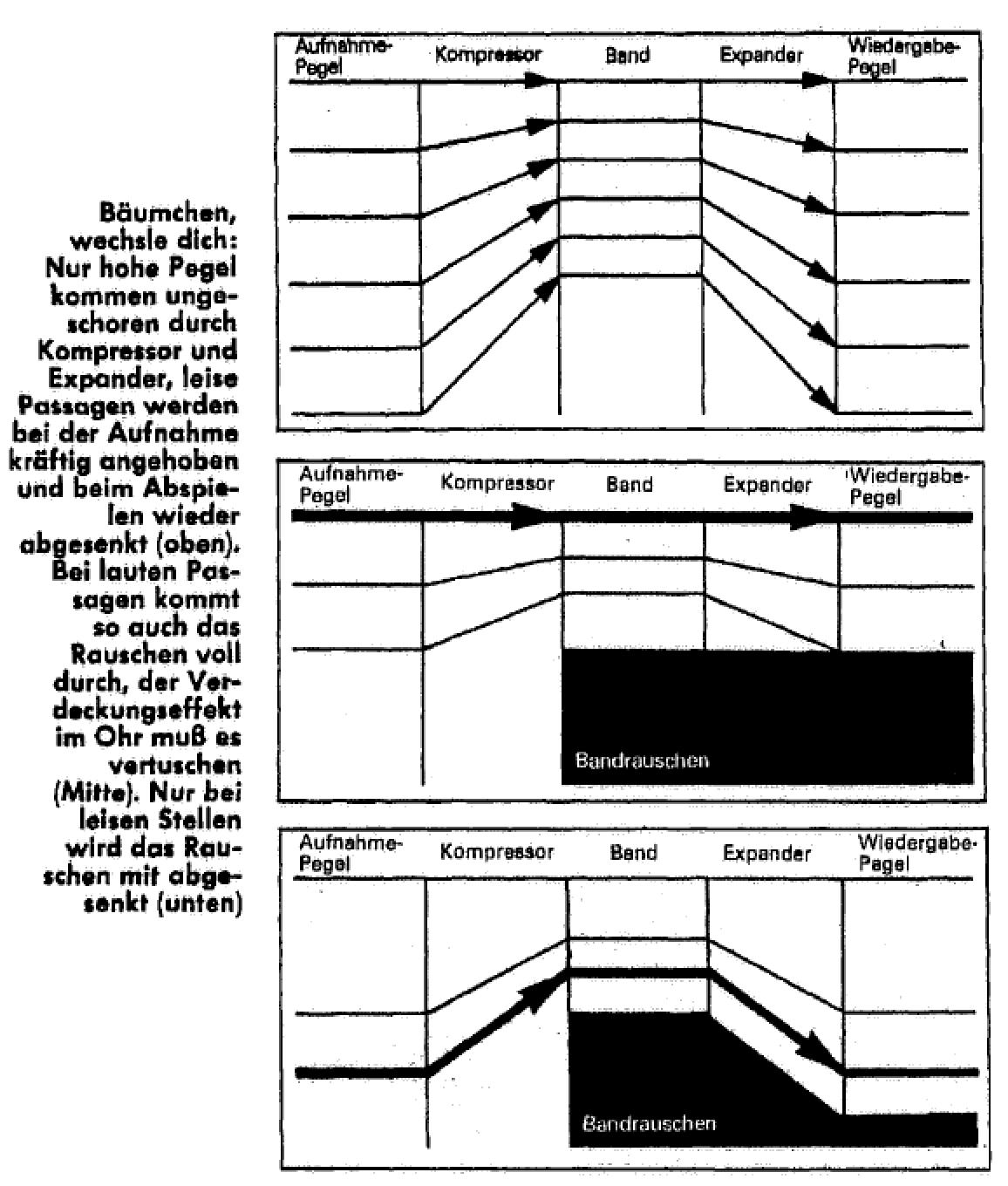

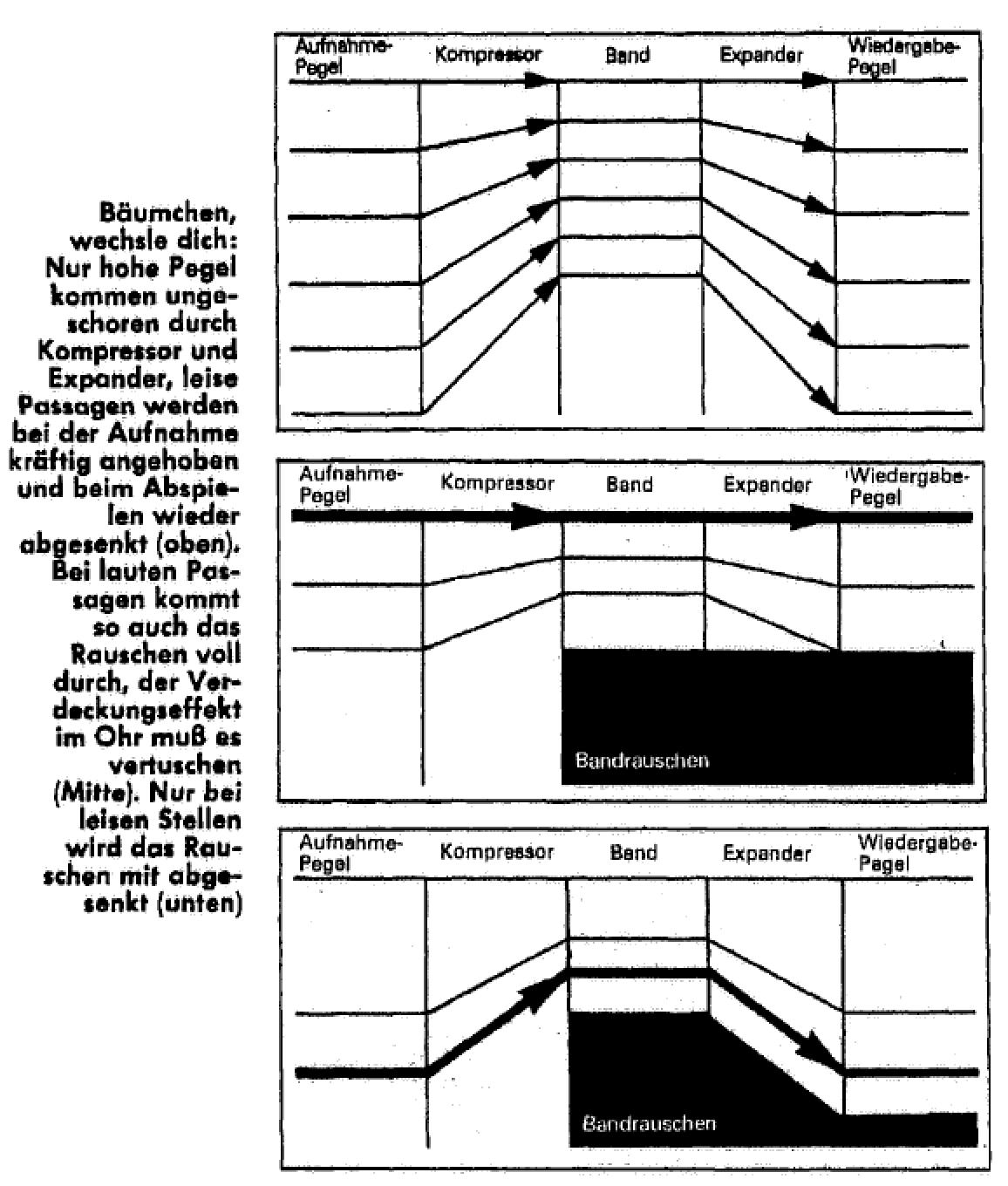

Jens Schröter’s essay, “On the History and Aesthetics of Noise Reduction,” delves into the significance of noise reduction in modern sound production. Schröter notes that while analog media technologies relied on noise reduction filtering, the advent of digital technologies has made these systems obsolete. He also highlights the aesthetic value of noise reduction, particularly in producing silence in cinema and experimental media aesthetics in electronic music.

Certain musicians and sound artists have employed various methods to critique and challenge power formations, leading to the creation of a sub-genre in the history of sound. “The Critique of Power Dynamics Through Sound” by Gregory Blair delves into the use of sound in music and art as a tool for political critique and disruption of power structures. Blair’s analysis examines how music and sound can be used to challenge power dynamics and societal norms that have become normalized. The paper provides a detailed analysis of three projects that showcase the critique of power dynamics through sound: Pussy Riot’s Punk Prayer, Samson Young’s Canon, and Selma Selman’s You Have No Idea.

Also taking into account “Sound Design for Electric Vehicles: Fulfilling Laws and Creating Digital Artwork,” Alessandro Fortino delves into the techniques of sound design used in the past for vehicles with internal combustion engines. His article highlights toolchains and creative approaches that transform EV sound into digital artwork, shedding light on how the sound design industry is adapting to the new demands of the electric vehicle era.

Additionally, concerning that AI companies are revolutionizing the traditional methods of replacing voices on set or creating foreign language versions of films. Ross Adrian Williams’ article, “Voice in the Machine: AI Voice Cloning in Film” delves into the emerging field of AI voice cloning in film production.

In the article, the author highlights the importance of a character’s voice in cinema, as it is closely linked to their body and movements and can define a character’s personality. William discusses the impact of AI voice cloning on film production, especially in automated dialogue replacement (ADR) and film localization.

Moreover, innovation is a powerful force that can cause significant changes in industrial, social, and cultural contexts. Technological advancements have often been the driving force behind such innovation and have given rise to entirely new art forms in the visual arts. While technology’s impact on aesthetic innovations in music may also be significant, it is worth exploring its potential in shaping the future of music. In that way, the article “Electronic Music: Utopias and Realities” by Thomas Neuhaus discusses the pioneers of technology who have always envisioned a utopian future.

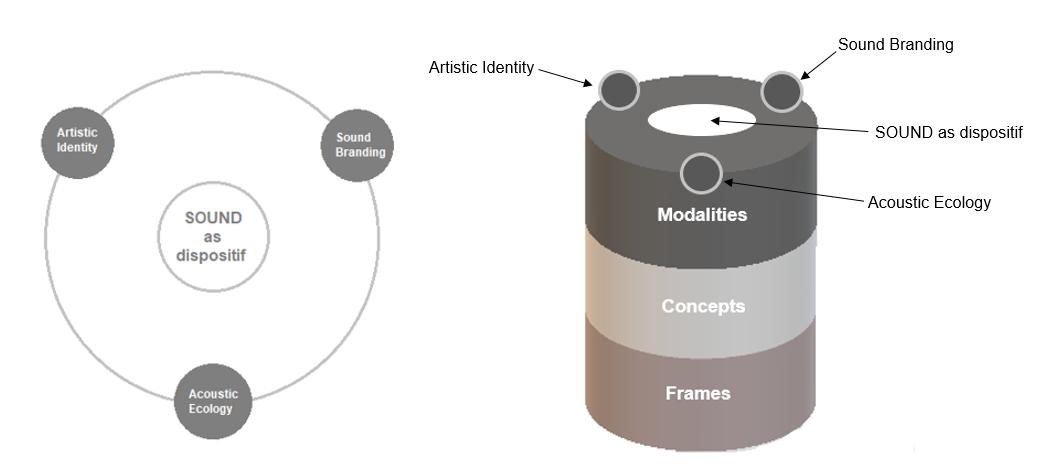

In “Listen Up! Strategies of Theatre Sound Towards Artistic Identity, Sonic Branding, and Acoustic Ecology,” David Roesner explores the relationship between sound and theatre, focusing on three main aspects: sound as a creative tool for the ensemble, sound as a branding element, and sound as a means of ethical exploration.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 9

Roesner underlines sound as an interdisciplinary subject closely linked to our identities, showcasing how contemporary European theatremakers use it to transform their creative processes, develop artistic identities, and investigate the relationship between music, voice, and sound with bodies, texts, and spaces. Additionally, he highlights the use of sound in branding efforts. Theatres can also serve as critiques of commercial sonification and as reflections on our rapidly changing acoustic ecology. Roesner provides two case studies to illustrate his points.

In addition, “The Audiovisual Chord: Invitation to a Dance Between Sound and Image” is an introduction to Martine Huvenne’s book The Audiovisual Chord: Embodied Listening in Film The book takes a phenomenological approach to film sound and is grounded in Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. It presents analytical tools such as sound as a dynamic transmodal movement, thinking in movement, auditory filmic space, and the audiovisual chord These tools enable the application of insights gained in filmmaking and film analysis. The book’s main case study is Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped (1956), presented as a phenomenological film. Bresson’s vision of film as a transmission of experience and presentation of a life-world is explored in detail.

As we near the end of this special edition, we have the pleasure of reading Jörg U. Lensing’s insightful article on the subject of film sound design. However, while almost all articles and books on this special topic almost always deal with Anglo-American films, J.U. Lensing analyses the introductions of six exemplary German films for their specific audio-visual interactions and in relation to a somewhat different understanding and aesthetics of what sound design can achieve for film.

Finally, Andreas Ammer wrote an afterword on “The Beginning and the End of the Radio Play,” which sheds light on the current state of radio plays. Radio plays were once a popular form of entertainment but have largely faded away in the digital age due to a lack of funding and competition with other forms of media. Despite these challenges, Ammer shows that some groups continue to create and promote radio plays to preserve this art form for future generations.

Such an endeavour always involves a great deal of work and requires the cooperation of specialists in their field. The editors Christiane Wagner and Jörg U. Lensing are therefore very grateful to have gained a total of 14 renowned authors on the subject of “acoustic pathways,” who were able to contribute topical articles on their subjects. This special issue of Art Style Magazine is a follow-up publication to Acoustic Turn (2008). It is due to the fact that the initiator of this project, Professor Jörg U. Lensing, primarily teaches and researches on the subject in Germany that the majority of the authors are originally German-speaking. Nevertheless, the subject areas are internationally relevant and this publication is intended as a contribution to the international discourse on the value of the auditory, particularly in the field of art and design.

Christiane Wagner Editor-in-Chief

Jörg U. Lensing Co-editor for this special edition

10 Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine

Immersive Music

Michel Chion

There is a current vogue in France concerning the words “immersive” and “experience” (the latter in the American sense). They are advertising new forms of shows, video games, performances, and concerts, as well as domestic listening and viewing installations, and I am constantly receiving information in my mailbox about artistic events promising “a sensory immersion.”

First of all, I am rather sceptical about this notion since, for the eye, it is only theoretical. Indeed, we cannot look around us without the obligation of moving, thus moving our limited visual field. Even a mirror, reflecting what is behind us, does not show us everything, and above all, it is impossible for us to embrace our entire visual field with just one glance.

On the other hand, when the term immersive is used to promise strong sensations, I would like to point out that already our daily reality is immersive, starting with the most banal experiences like lying in bed, being cold, going shopping, rolling in a car, and so on... So, I don’t see what is considered to be so interesting in experiencing a situation of “sensory immersion.”

In my view, a work of art, or a musical or dramatic experience, has the advantage of being non-immersive. A work of art, a play, a performance, or a show in the childish sense of magic and puppets, they do charm our eyes and our ears exactly because there is something being presented in front of us, and we can only project ourselves in a show (visual, sound, etc.) precisely because we are not being immersed by it.

This is why I am not the only one to demand that the audience be oriented in just one direction, the same for all listeners when one of my works is performed on an orchestra of loudspeakers (acousmonium). In fact, I want the audience to be oriented towards an acoustic stage on which a good part of these loudspeakers is installed.

Sure, a certain pleasure can be found in so-called attractions like bumper cars, ghost trains with phonic sensations, thus a feeling of being moved and shaken but can we consider this as being aesthetic? On the other hand, since words like “immersive” are used as commercial arguments, what desires do they serve or correspond to? Do we want to evoke a fusion with an environment in the same way we perceive a fish in water? Is it about making the entire body vibrate, as music, played at a very high level, allows a kind of feeling of being carried like a child, thus a feeling associated with a regressive form of well-being?

11 Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine Foreword

Sound, in musical or non-musical form, has long been a means that seems most conducive to “immersion.” By its nature, it potentially addresses two senses: hearing and feeling. By this, I mean that the same cause, a sound wave, can produce in us two distinct physical effects, but they are wrongly taken for one sensation, and this is for the only reason that they are happening simultaneously.

A sound can indeed address both the ear and the body. In what I call the auditory window (vibrations that the ears pick up and transform into an acoustic sensation), we hear sound objects that are more or less melodic, shaped, continuous, or discontinuous, that have a matter, a pitch, have or do not have a mass, a spatial path, etc. At the same time, if this sound is loud and has low frequencies, we feel disruptions in other parts of our body, vibrations that are missing textural qualities but that are able to make us want to move and dance just naturally when this rhythm is being pulsed. I call this reaction to certain sounds (not all of them) a reaction of the body, things, and objects that I call a co-vibration It is to this covibration that Martin Luther alludes when he writes in one of his hymns:

Heilig ist Gott, der Herre Zebaoth, Sein Ehr die ganze Welt erfüllet hat, Von dem Geschrei zittert Schwell und Balken gar,

Or else Georg Trakl: Sanfte Glocken durchzittern die Brust.

Or Virginia Woolf in her novel Mrs Dalloway: The throb of the motor engines sounded like a pulse irregularly drumming through an entire body.

Some low frequencies at a certain level of intensity cause the listener’s body to resonate in co-vibration while at the same time drawing an acoustic picture in the “auditory window” of our ear However, due to their lower intensity and highfrequency spectrum, other sounds simply fit into the window in question and do not evoke co-vibrations.

Consequently, as I said, we are left to assume that the simultaneous sensations of sound object, acoustic figure (in the auditory window), and bodily co-vibration are identified and referred to by the same word, “sound.” This is in spite of the fact that they are profoundly different. And this is happening only because they are perceived as being the effect of these causes and because they occur simultaneously. In the same way, a specific perception of light that would be systematically associated in synchrony with a specific perception of sound cannot be separated and consciously isolated from each other. They would be perceived as “the same ” thing in two forms.

In short, what we call “the” sound its singular needs to be questioned indeed could then, in certain specific cases, be bi-sensorial (i.e., affecting two senses at the same time).

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 12

This would be one of the reasons why the physical, “immersive” investment of the viewer/listener is more immediate and irrepressible via sound than via picture, the latter being monosensorial. Other reasons for this difference in physical investment lie in the impossibility of “turning away from listening” in the same way as one can turn away from looking, as well as in the frequently non-directional character of sound, thus allowing certain sounds to surround us.

For a long time, only certain specific musical forms military music or certain dance music made extensive use of sounds that produced intense co-vibrations, inviting movement. But this required live performers and instruments with a large range.

However, current technology makes it possible to use recorded sounds that do not ‘tire’ and amplify them to high power. Some hi -fi brands have developed a new generation of loudspeakers. Very small in volume, they are able to produce an intense sound with a strong bass. These speakers can be connected via Bluetooth to a mobile phone and, on the latter, to virtually endless playlists, which provoke “immersive” sensations whose vibrations create a feeling of being carried.

In France, immersive art is fashionable, especially for music, and there are already ‘immersive art manifestos.’ Is this the future of music? Is it only possible form from now on? I do not think so.

It turns out that the electro-acoustic means that I have been using for the last fifty years to compose works of concrete music can be used for making “immersive” music, inhabiting all space and time uninterruptedly and uniformly, without gaps, without holes, and striking the body. However, these means are as suitable for making music that, by the opposition, I would call “emersive:” a music that presents itself in the form of a work of art, music that obeys a form. This form creates conditions for an “emergence,” an event.

The most common form of novel and drama, form and narration, can highlight an event that can be spectacular but also discreet, humble, and intimate, and this can even happen in non-narrative music.

For example, let ’ s look at the beginning of my Requiem, composed in 1973. I have chosen to attack the first movement of this 37-minute work with a sharp, brutal sound that stops after about 40 seconds. Even in a concert, the listener cannot anticipate this brutal attack since the sound comes from loudspeakers and not from an instrument. Then, a male voice is heard saying a short introductory text. Only then, with a piano intensity, do electronic chords begin, from which, gradually, two other voices emerge, a whispered female voice and a male voice heard from a distance. At first, they are barely audible, but thanks to the concentration I have created by starting with a violent sound and then giving it up, the audience is able to taste the intimate character of this duo, almost sexual, I was often told, although this was not conscious on my part when I composed it.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 13

Even though I, who composed this music fifty years ago, heard and played it very often, I am still moved by this passage of vocal intimacy: it only lasts a few seconds, but I am happy that I created the conditions for these few seconds. They only exist due to the context of the whole work.

This moment is indeed the result of a general form, and this must be emphasized. At this point in the concert, I only use a few loudspeakers, choosing those in front of the listeners. At other moments in the Requiem (the beginning of the Evangile), the emergence of a moment is created by opposite means: an explosion of sound that occurs from all sides at once.

In a much more abstract work like my Sonate en trois mouvements, my ThreeMovement Sonata, which I composed in 1990, the event is constituted by a ‘false ending’ in the course of the second movement: when it seems to have ended after a brief silence, it resumes for a few seconds from sounds similar to those already heard, but filtered, as if reappearing in a dream.

For a musical work, concrete or not, to be “emersive,” it is necessary that it does not occupy time in an equal, continuous, regular way... and that it does not occupy space and our body in a constant way, by regular co-vibrations. A work like the Requiem and the others that I composed thereafter and in the course of half a century all of them aim, among other things, at creating such moments in which one is invited to listen, in which one creates the conditions of an opening, in which one recreates a new space of attention, and at the same time in which one makes space happen.

In his diary Am Felsfenster morgens (und andere Ortszeiten 1982-1987), Peter Handke writes:

Jetzt weiß ich, was mich so stört an der meisten Musik: sie nimmt mir den Raum; sie verzerrt ihn (Nacht, Garten, Grillen).

With the means given to me by concrete music (which allows me, for example, to create sudden silences, real silences, by making the sound interrupt radically, without anything visible announcing the interruption), I also seek to recreate space, to allow us feeling it again, to make it happen. Immersive forms of music are destroying this space

Michel Chion is a French film theorist , composer of experimental music and associate professor at the University of Paris III (Sorbonne Nouvelle)

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 14

Soundscape Selected Historical and Aesthetic Perspectives1

Sabine Breitsameter

Abstract

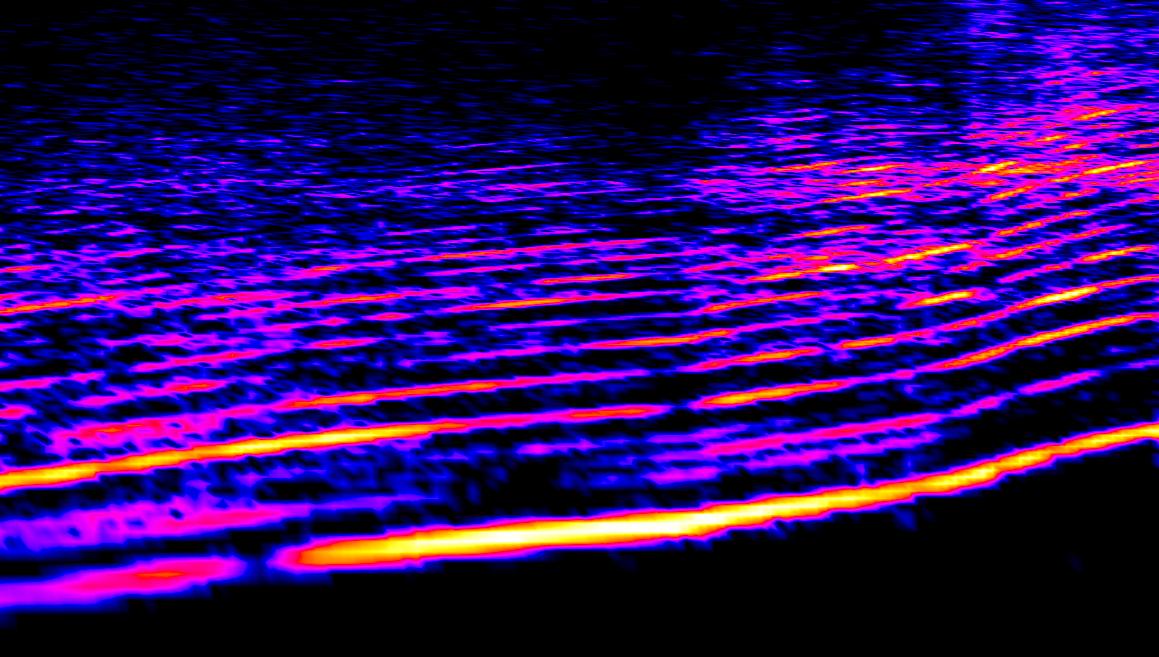

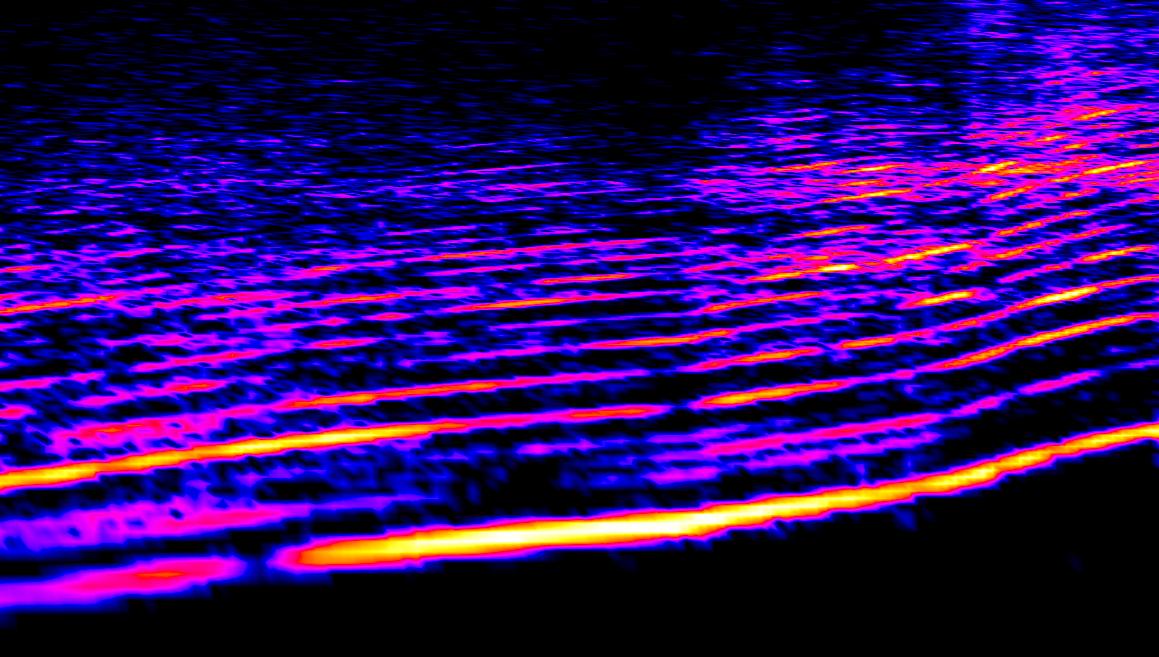

The neologism soundscape refers to the acoustic envelope that surrounds the listener. Since the late 1970s it has become continuously popular. In recent years, there has been increasing criticism that the term soundscape is used blurrily and arbitrarily, and thus risks to lose its explanatory power in artistic and scientific discourse. Yet soundscape is more than just a term: it stands for a paradigm. In the following, the origins, prerequisites, implications, consequences, and perspectives of the term soundscape will be explained in order to make its core accessible and its original intensions clear: The soundscape concept leads to an aesthetic perspective that consistently approaches the world and its auditory phenomena from the perspective of hearing, encouraging people to change focus and thereby enabling an alternative world “picture ” At the same time, the holistic acoustic environmental experience that the term implies, in the context of R. Murray Schafer’s theory of Acoustic Ecology, becomes tangible as an expression of the society from which it emerges: a soundscape is a reflection of a specific society’s conditions, tensions, and namely its ecological conflicts. Finally, since the 1970s, the Soundscape Studies have been establishing a vocabulary for the description of the auditory world and its phenomena that makes the important elements of acoustic environmental experience conceptually comprehensible and thus sustainably accessible to scientific as well as aesthetic reflection. By demonstrating why the world sounds the way it does, the soundscape paradigm also opens up starting points for its applied design and the artistic forms that emerge from it. This is especially important with regard to the upcoming immersive technologies and the audiomedial forms of experience that derive from them.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 17

Terminological Considerations

The term ‘soundscape’ emerged at the end of the 1960s in the North American Sprachraum (anglophone region). As one might surmise, it is a combination of the words ‘sound’ and ‘landscape’ An early use of the term was documented in 1966 by Richard Buckminster Fuller, who wrote,

When man invented words and music he altered the soundscape, and the soundscape altered man. The epigenetic evolution interacting progressively between humanity and his soundscape has been profound.2

Buckminster Fuller thus describes a dynamic interrelationship between humans and their acoustic environment, in which both exert a formative force upon each other. In 1967, architect Michael Southworth used the term to describe acoustic manifestations of urban space that he had mapped.3 Subsequently, the term was taken up by the Canadian music educator and composer R. Murray Schafer, who used this term which had clearly made its mark on him in order to understand the auditory phenomena of everyday life in their entirety, to perceive them attentively on this basis, and to be able to subject them to a critical evaluation.4

Since then, the term ‘soundscape’ has encompassed the perceived totality of all acoustic phenomena that occur in specific places, spaces, or landscapes. The environmental sounds are, first and foremost, representatives of a given spatial or local situation and its geographical, cultural, technical, and social peculiarities. A village in the desert has a different soundscape than a village by the sea. A Chinese city in an industrial region sounds different from the industrialized urbanity of Central Europe. Forests, mountains and climate can be reflected in a soundscape just as much as religion, architecture, the degree of technologization of a society and many other contexts.

Generally speaking, in a soundscape not only geographical and physical conditions can manifest themselves auditorily, but also flora and fauna, language, social values, communication behavior, everyday activities, and the many practical aspects of the interaction between humans, nature, and technology. The term ‘soundscape’ is also applicable to closed spaces, such as a concert hall, office, or apartment, as well as to artistically created, media-related, and virtual spaces, such as a composition, a radio program, or a computer game.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 18

When compositions are presented, an entirely new sound environment is created with its own sonic atmosphere and its own timespan of listening. Any music and its use in any context (whether in a performance situation or in a mall) is just as much a sound source of environmental concern as, say, car motors or dog barks.5 What is perceptible in a soundscape goes far beyond representation and signifying. The auditory acquisition of an environment and its surroundings that a person is accustomed to accessing visually acts to reconfigure perception in an essential way. Only rarely does the auditory thereby take on a delineated representationality that can be concretely differentiated from other auditory objects. Rather, the sounds of a place or a landscape merge into a totality that is fundamentally different from visual perception and its ability to grasp something in an instant. To present themselves, sounds require time. A soundscape transposes the visual moment into the auditory duration. If the term ‘soundscape’ is about “seeing the landscape with the ears,” as Murray Schafer described it in a WDR radio interview in 1998,6 then the shift from seeing to hearing refers equally to a perceptual attitude in which it is not so much the ‘thing-ness’ that can be experienced but, primarily, the process.

From this confluence of all sounds in a particular soundscape, a distinctive sonic ‘appearance’ can emerge, an acoustic peculiarity or identity that is similarly characteristic to a specific visible manifestation. If one identifies the sounds by which a specific soundscape is characterized, one can also obtain information about the central values of a society, its priorities, deficits, power structures, and its ecological state. Which auditory events are dominant despite irritating or totally disturbing the listener? Which auditory events do not occur or are inaccessible to the sense of hearing, and for what reason? Which soundscapes are unwholesome, noisy, or repellant, and which contain elements that got out of proportion? Which social priorities contribute to the fact that places, spaces, and landscapes sound the way they do? It is precisely these questions that crystallize the socio-critical impetus inherent in the term ‘soundscape’.

An important precursor of the soundscape concept can be found, in particular, in Luigi Russolo’s manifesto L’Arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noise, 1913), in which he points to the acoustic phenomena of the industrial age as the starting point of what he calls a newly emerging mode of listening and musical aesthetics: “We Futurists have all deeply loved and savored the harmonies of the great masters (...).”7

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 19

If we pass through a modern metropolis with more attentive ears than eyes, we will be lucky to distinguish the suction of the water, the air or the gas in the metal tubes, the hum of the engines that undoubtedly breathe and quiver like animals, the knocking of the valves, the rise and fall of the pistons, the screeching of the sawmills, the jumps of the streetcar on the rails, the cracking of the whips and the rustling of curtains and flags. We enjoy distinguishing in our minds the noise of the window blinds, of the stores, of the slammed doors, the din and scrape of the crowd, the various sounds of the stations, the spinning mills, the printing presses, the electric power plants, and the subways.8

In this description, Russolo already anticipates in addition to the aestheticization of everyday sounds a number of characteristics of Schafer’s later soundscape concept, in particular the attention to sounds that are usually ignored, the dynamic experience of the listener by means of a ‘sound walk’, and the aspect of orchestration, meaning the deliberately designed symphony of all sounds (“acoustic design”) in the urban sound concert.

Another hitherto little-known vanguard who designed, described, and also mapped the landscape namely the natural landscape as an acoustic concept was the Finnish geographer Johannes Gabriel Granö (1929).9

While the term ‘soundscape’ began to establish itself in the Sprachraum of North America as early as the 1970s, it reached Europe in the mid-1980s, where the idea first became known to a wider audience under the term Lautsphäre (soundsphere) in the early 1990s.10 For the term ‘soundscape’, which was translated inconsistently, the more specific German translation Klanglandschaft 11 (essentially a one-to-one translation of the two root words) was then found. In the late 1990s the original English-language term began to prevail, and has now also established itself in German. The use of the English term has the advantage that it is no longer so clearly framed by geographical connotations, but it does have the disadvantage that it is often used in a very generic sense, even becoming generalized beyond recognition.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 20

Implications of the Term ‘Soundscape’

R. Murray Schafer conceptualized the soundscape within the framework of his teachings on acoustic ecology, which studies the interrelationship between living beings and their environment. It relates the quality of the acoustic environment directly to the significance of listening in a society, in particular to the degree of physiological ability and mental readiness to listen attentively. This is a concern decisive for Schafer’s teachings. In his main work The Tuning of the World (1977), he unfolds a cultural history of listening, establishing a close connection between the listening experiences of various historical epochs (such as Antiquity, the Industrial Revolution, and the Electrical Revolution) and the significance of listening, as well as the auditory practices in the respective society.

Schafer’s springboard is the noise pollution of the late 1960s. Due to the increase in car and air traffic, the construction noise associated with the expansion of cities, and the proliferation of the music amplifier, acoustic ecology not only addresses hearing damage and auditory overload, but also works out the structural conditions of wanting to and being able to listen. As early as the beginning of the 1960s, Schafer’s experience as a music teacher was that many of his students found it increasingly difficult to listen intently and actively for extended periods of time, whether to music or the spoken word. However, Schafer did not look for a solution to the problem in an adaptation of the content (“Beatles instead of Bach”), but looked at the overall situation. He found that in an everyday life characterized by uncontrolled acoustic expansion one that barely offers any intentionally designed input for the ear, and fails to actively avoid unpleasant, communicatively empty and meaningless sound events the majority of people would not expect anything worth hearing and would thus keep their ears closed. An out-of-control, repugnant acoustical environment has conditioned its inhabitants to dull their hearing and abandon the auditory world to indifference. Experiences shape expectations. What one does not become acquainted with, what is not imaginable, what is no longer listened to, becomes inaudible, and thus non-existent.

Implicitly connected to Ernst Haeckel’s systemic idea of oecology (1866), Schafer’s concept of soundscape combines listener, sounds and environment into an “entirety,” a dynamic system in which the change of one factor influences all other factors and finally the auditory result itself.12 According to Schafer, an acoustically well-designed world based on conducive, livable and aesthetic soundscapes would be a necessary prerequisite for a general social appreciation of the auditory and the promotion of auditory reception and attention in general.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 21

Within this framework, Schafer understands soundscape as a counterpoint to a listening that is selective and completely frontally oriented. Such a concept has developed as a result of (here he borrows from Marshall McLuhan13) a predominantly visual and frontally oriented culture. Its attitudes and practices have been largely adopted by the other senses. In the “system soundscape,” the listener must therefore be reconceptualized namely, no longer as a passive and frontal receiver or positioned at a privileged “sweet spot,” but as a living, agile element that contributes to and influences the soundscape. Thus, perceiving a soundscape always connotes participating in it and being “inside” it.

Elements of the Soundscape

Schafer simultaneously developed terminological and perceptual categories by which soundscapes can be described and analyzed. The three most important are ‘keynote sound’, ‘signal,’ and ‘soundmark ’ With these distinctions, Schafer transfers central principles of visual Gestalt psychology to the auditory, in particular the relationship between figure and ground. According to this categorization, the term ‘keynote sound’ refers to a permanently present sound that is characteristic of a place and is a foundation for all the other sounds there. This can be, for example, the sound of the sea that characterizes a particular beach hotel, or the hum of a highway that one hears from a distance, or the characteristic buzzing of a refrigerator in a particular apartment.

Keynote sounds have an effect over a certain duration. Above all, they establish atmosphere. A soundmark, on the other hand, is something more momentary. The word is rather obviously derived from the term ‘landmark ’ However, an acoustic landmark, or signifier, is usually less easy to identify than a visual one. The ringing of Big Ben’s bells, for example, is considered an acoustic landmark of London. The whistles and horns of trains in Canada can be considered a soundmark of the Canadian landscape. The characteristic door-closing sound of certain makes of car also counts as a soundmark. Any sound event that emerges specifically for a place, space, or object as a single, clearly outlined sound can be called a soundmark. The ‘signal’ also appears in the foreground and therefore figurally. An auditory phenomenon becomes a signal when it communicates a message. Signals are coded, such as the sound of the post horn, the ringing of the telephone, the wailing of the police siren, and so on.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 22

Schafer makes an important distinction between so-called hi-fi and lo-fi soundscapes. While hi-fi, according to Schafer, means the transparent audibility of an acoustic environment in which all sounds can be clearly heard and spatially located and even distant, quieter sounds can be perceived a lo-fi soundscape is understood to be a broadband “wall of noise” that overlays and masks other sounds that occur, thus narrowing the acoustic horizon. Lo-fi soundscapes are usually perceived as more irritating than hi-fi soundscapes. Lo-fi is rather typical for urban soundscapes, although not in every case. The broadband noise, such as that of perpetual car sounds, rattling air conditioners, or vibrating construction machines, often masks fine and distant sounds, thus making them inaccessible to hearing. Subtle sounds such as people breathing, and distant sounds such as the footsteps of passersby across the street, are not readily accessible in lo-fi environments. From the perspective of acoustic ecology, hi-fi environments are more desirable.

Schafer is sometimes criticized for harboring hostility to technology and to the present, since the lo-fi soundscape, which he favors less, occurs mainly in environments characterized by technology and urbanity, and thus has a generally negative connotation. However, this criticism only applies to a quite limited extent, since Schafer’s critical attitude towards lo-fi soundscapes does not refer to the causative mechanisms per se, but rather to the effect of auditory leveling and the associated loss of a diverse, unrestricted listening. This criticism thus fails to recognize that Schafer’s argument here is primarily descriptive and phenomenological, that is, guided by the effect rather than the cause. Moreover, he repeatedly refers to the positive effects of a conscious soundscape design made possible by technological development through a criteria-based acoustic design yet to be developed. 14

The World Soundscape Project and Similar Undertakings

After R. Murray Schafer was appointed to Simon Fraser University in Burnaby near Vancouver in the late 1960s, he founded the World Soundscape Project as part of his research work there.15 His goal was to archive and analyze the acoustic phenomena of places and landscapes worldwide, and to record their changes over decades. Collaborators on the World Soundscape Project included the now renowned soundscape composers Hildegard Westerkamp and Barry Truax.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 23

In the early 1970s, Schafer’s team also began to study their own city of Vancouver on Canada’s west coast. The sounds that were contemporary there at the time were initially compared with descriptions of soundscapes found in books and newspapers from the beginning of the 20th century. These sounds were also examined for future changes that were on the horizon for the urban soundscape of the 1970s, which included airport expansion, increasing road traffic, elimination of the characteristic signal horns in shipping, gentrification of the city, and increasingly multicultural daily life, among others. All of this, Schafer’s research team realized, would very soon and fundamentally change Vancouver’s acoustic identity.

The technically outstanding sound recordings that were made as part of the World Soundscape Project (which is still ongoing) are available in an archive at Simon Fraser University.16 They are not only of considerable historical and documentary value, but also of great aesthetic poignancy. This is one of the reasons why many of these recordings became the origin for various soundscape compositions, including within the Soundscape Vancouver Project (1995), in which the recordings from the 1970s by four composers 17 served as the starting point for their own creations (Figs 1-5) 18

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 24

Figure 1. Soundscape Vancouver Project.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 25

Figure 2. Soundscape Vancouver Project.

Figure 3. Soundscape Vancouver Project.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 26

Figure 4. Soundscape Vancouver Project.

Figure 5. Soundscape Vancouver Project.

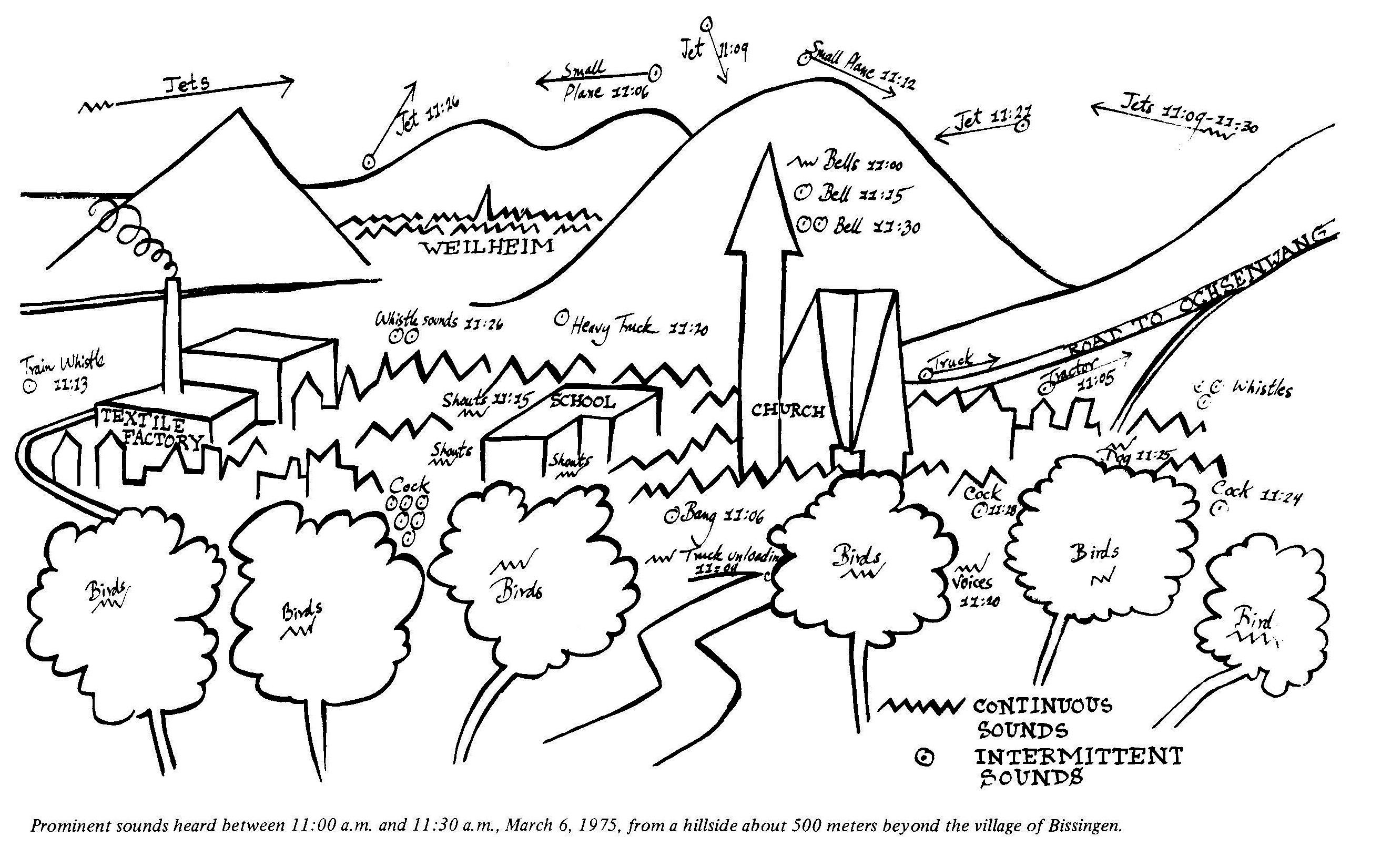

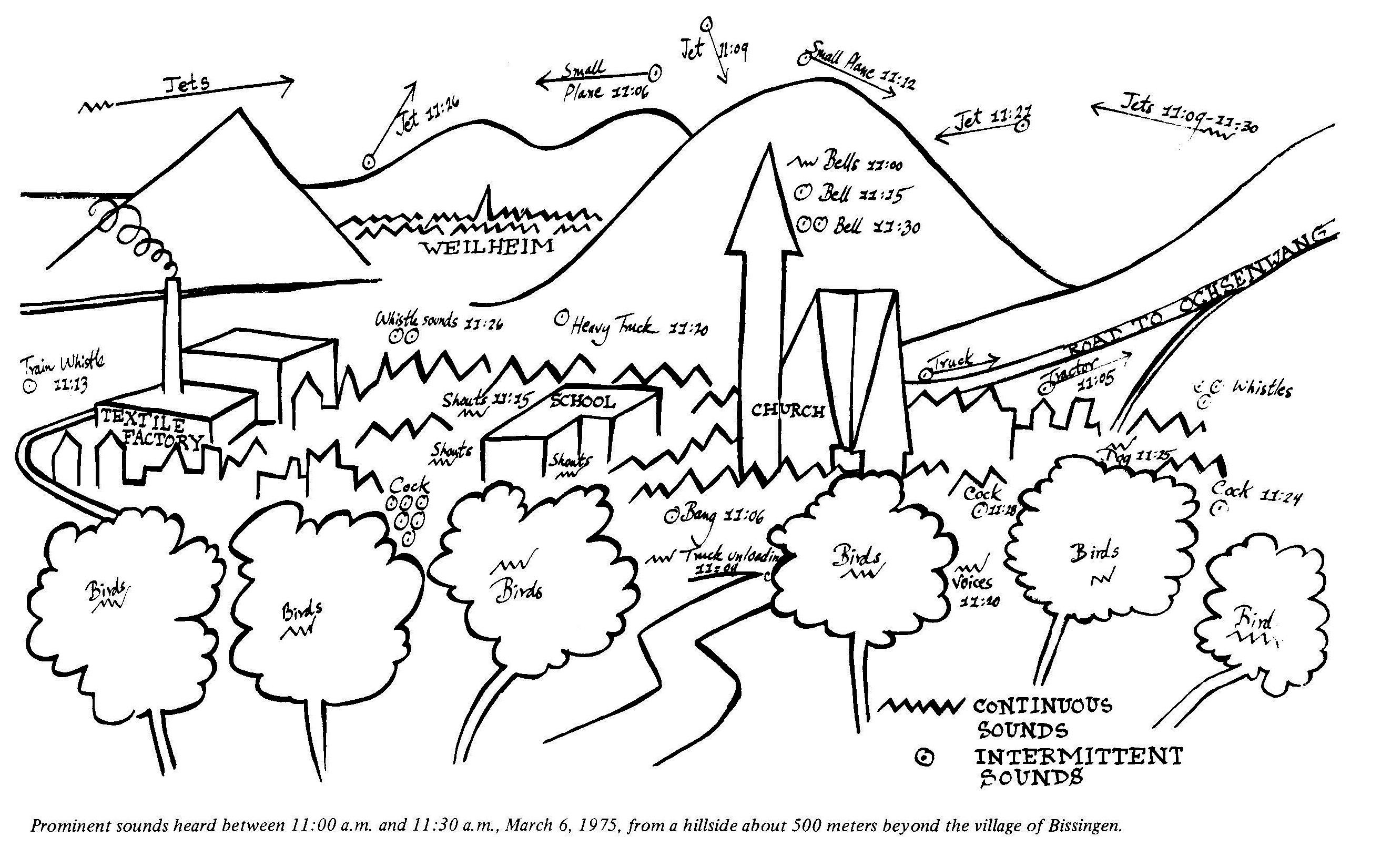

In 1975, a research group led by Schafer traveled to Europe to investigate sites there as part of the Five Village Soundscape research project. The group chose the respective places based on the criteria that the location should still present soundscapes largely uninfluenced by traffic and industrial noise, and that traditional soundmarks should still be noticeable. The sites were Skruv in Sweden, Bissingen in Germany, Cembra in Italy, Lesconil in France, and Dollar in Scotland. In 2009, the same places were visited again by a Finnish research group and studied for their changes, especially with regard to the effects of urbanization on the respective soundscapes. This was done under the direction of Helmi Järviluoma, Heikki Uimonen, and Noora Vikman, with the collaboration of Barry Truax, who was a member of the 1975 Canadian group. 19

Soundscape Composition

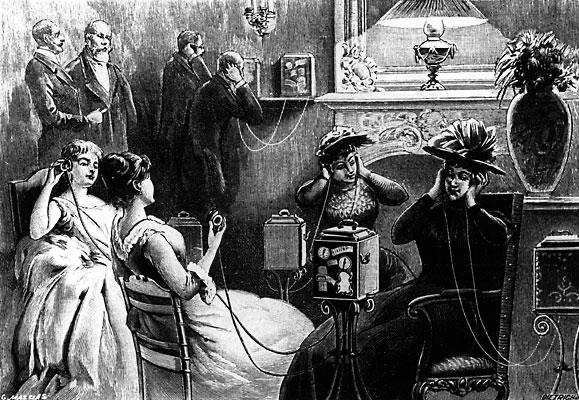

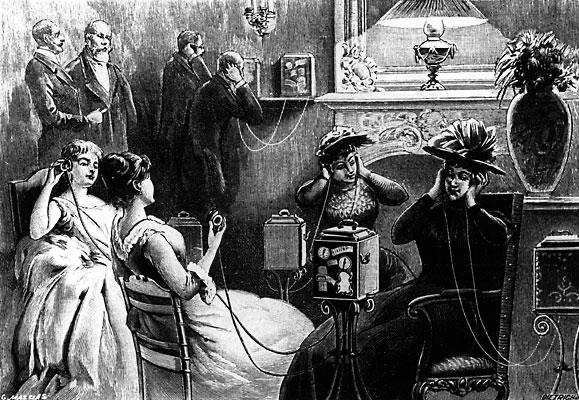

Beginning in the 1920s, environmental sounds began to establish themselves as integral components of the artistic material canon. The conventional distinction between music worthy of being listened to on the one hand, and unappealing, unremarkable everyday noise on the other began to dissolve. The composer Kurt Weill, the radio producer Hans Flesch, the film artists Dziga Vertov and Walter Ruttmann, and the media scientist Rudolf Arnheim all stood in the mid to late 1920s for a conceptual and compositional development that gave the noise of the everyday environment a prominent and central position. They postulated this noise as being equal in status to musical sound or the spoken word. According to the radio pioneer Hans Flesch, this gave rise to an innovative form of auditory art that could no longer be captured by the traditional concept of music, and which was compelled forward by the new medium of radio. Groundbreaking in many respects was Walter Ruttmann’s audio production Weekend in 1929, which chronologically arranged the significant sounds of a Berlin weekend and ingeniously captured them aurally and montaged them.

The artistic positions of the 1920s described above were primarily concerned with opening up new compositional material and thereby also recognizably incorporating “reality,” the world of labour and machines, and everyday life. In contrast, the Musique Concrète that emerged in the 1940s, which also took everyday noise as its point of departure, favored an abstracting expansion of the palette of sound material beyond semantic echoes. The simultaneously emerging sound experiments of John Cage (4’33” or Imaginary Landscape No. 2, for example) aimed at questioning traditional concepts of perceiving music. Even if soundscape composition differs from the artistic positioning referenced here, it intersects considerably with them in each case.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 27

Luc Ferrari’s compositional approach of a Musique Anecdotique, which emerged in the early 1960s as a critical reflex of Musique Concrète, already draws nearer to the idea of soundscape composition and is sometimes also actually referred to as an early soundscape composition.20 Ferrari used recordings of everyday situations, the immediate content of which is unabstracted and directly narrative in its aural presence, which is both scenically and semantically concrete, but at the same time also unfolds sound-aesthetic and poetic qualities.21

Soundscape composition as its own genre, which emerged in the mid to late 1970s, was defined in particular by composers Hildegard Westerkamp and Barry Truax.22 It is an electroacoustic genre that procures specific and identifiable sounds from the acoustic environment as its starting point. Westerkamp points out that soundscape compositions themselves are never abstract, but the recorded environmental sounds can very well be subjected to abstracting electroacoustic editing processes.23 In her own compositions, for example, Westerkamp often works with slowing down or speeding up the sound material, or with clever cuts that decontextualize the material, thus detaching it from its semantic context and making it accessible to aesthetic reception apart from a semantic binding. Barry Truax applies granular synthesis, in particular, to his soundscape materials.

The soundscape composition is characterized above all by the fact that it conveys, as a basic compositional intention, its interest in the acoustic environment per se or in a specific soundscape an interest that is shaped by the individual attitude of the respective composer.

Soundscape composition is as much a comment on the environment as it is a revelation of the composer’s sonic visions, experiences, and attitudes towards the soundscape. Audio technology allows us as composers to sort out the many impressions that we encounter in an often chaotic, difficult sound world. 24

Common to the soundscape compositions is an approach that makes one’s own critical listening to the everyday environment the starting point of the respective artistic concept.

... the soundscape composer’s attention to ecological issues of the soundscape ideally extends beyond the compositional process in the studio: it starts with listening as a conscious practice in daily life, continues during the acquisition of sound materials, the work in the studio, right through to the presentation of the final piece.25

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 28

An important artistic goal of soundscape composition is thus not to transport “reality” through the composition, but the emergence of aesthetic qualities and special features in what is already taken for granted and known: the breaking of perceptual routines and a new, intensified perception of what is already known.26 The artistic goal is mostly based on an aesthetic-instructive goal, namely to increase the listener’s appreciation of the acoustic environment.27

Outstanding soundscape compositions include A Sound Map of the Hudson River (1989) by Annea Lockwood, Basilica (1992) by Barry Truax, and Kits Beach Soundwalk (1981) and Into India (1995) by Hildegard Westerkamp. However, numerous pieces produced for radio play and artistic radio documentary formats also meet the criteria for a soundscape composition, such as Ritratto di Città (1954) by Luciano Berio/Bruno Maderna, The Solitude Trilogy (1969-76) by Glenn Gould, A Winter Diary (1998) by Murray Schafer and Claude Schryer, and Lezioni di Musica (1994) by Stefano Giannotti. Ros Bandt (Australia), Susan Frykberg (New Zealand), Andra McCartney (Canada), and Francisco Lopez (Portugal) have extensive oeuvres in the field of soundscape composition and have each individually expanded the concept of the genre as defined by Westerkamp and Truax. Among the composers of a younger generation who also deal with questions of acoustic ecology are Darren Copeland, Carmen Braden (both from Canada), Leah Barclay (Australia) and Lasse Marc Riek (Germany).

Criticism at the Soundscape Terminus

Exemplary for the criticism of the term ‘soundscape’ are the remarks of the British anthropologist Timothy Ingold.28 He takes offense at the fact that listening from the perspective of soundscape deprives the perceiver of other sensory experiences, such as visual, tactile, and olfactory experiences, among others, and consequently proclaims an alarming sensory reduction. Murray Schafer, however, has repeatedly emphasized the need for sensory wholeness.29 Ingold also fails to recognize that it makes sense to consider the auditory phenomena of the world separately in order to be able to investigate their manifestations and inherent laws, if necessary, so that they can be transdisciplinarily integrated according to Schafer’s declared intention “into the general study of the environment (...).”30 Ingold’s critique would structurally apply much more to disciplines such as art history and architecture, in which visual phenomena are usually studied in isolation from other modes of perception. A focus on exclusively visual perception is only rarely questioned.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 29

Ingold’s criticism also starts from the fact that the term ‘soundscape’ is often identified with the process of hearing, and implies the world of the auditory as something object-like. Ingold does not provide any evidence or citations for this, which makes it difficult to comprehend his critical approach in the fundamentality he postulates, especially since he presupposes a dynamic interrelationship between the listener and the auditory phenomena, and is thus fundamentally and inextricably tied to considerations of process.31 However, his position becomes understandable with regard to what has often become an unreflected and very generic use of the term, with which the everyday world of sounds per se is boiled down to an undifferentiated, auditory “form of intuition” in the sense of an observation category called soundscape, without taking into account that this term is actually a process-oriented concept.

Soundscape as Auditory Gestalt and Figure of Thought

Most often, soundscape is treated as an empirical phenomenon as something that “exists” and can be pragmatically perceived with the “correct” allencompassing listening attitude. However, this runs the risk of misjudging the highly conceptual character of the term ‘soundscape’. The landscape-oriented perception of sounds simultaneously and holistically-comprehensively constructs an auditory gestalt transcending ingrained listening habits. This is a comprehensive gestalt, down to the quietest, most inconspicuous sound. The term ‘soundscape’ thus directs auditory perception towards a spherical 360° hearing, in which every sound has its position in three-dimensional space and in which no distinction is made between important and unimportant, loud and soft sounds. This “formative listening”32 elicits a model that no longer separates between desirable and ignored sounds, no longer promoting a hierarchy between signal and noise. All present sounds are equally important for the auditory appropriation of the environment. Even that which does not occur plays a major role, as reflection on absent or missing sounds contributes enormously to a deepening understanding of a soundscape.

The term ‘soundscape’ is also a figure of thought that reformulates auditory perception. The spherical listening demanded by soundscape sets itself apart from frontal reception as cultivated in reading, stage situations, stereophonic listening (via radio, television, and music systems) or in traditional school lessons. With the soundscape, Schafer replaces inherited frontal concepts of perception and linear patterns of auditory presentation and communication with an audio-

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 30

tactile, lifeworld model. Within the soundscape’s cognitive figure of thought, the sounds to be examined by the ear do not exist “objectified,” but rather contextualized in mutual influence and impression in relation to the listeners. The term ‘soundscape’ thus represents a systemic concept.

Perspectives

In view of the proliferation of immersive media, which provide the recipient with an aesthetically consistent all-round experience, the term ‘soundscape’ occupies a key conceptual position, not only in the design and composition of auditory environments in the field of 360° media and virtual reality, but also in the construction of technologies and programs by means of which immersion and allround experience can be acoustically realized. Soundscape’s elements, as well as the structural considerations underlying the term ‘soundscape’, offer helpful basic constructs for the technical development and realization of design parameters. The cultural and aesthetic aspects of the soundscape concept, especially those that identify the role of the listener as part of the environment, specify the designdramaturgical forms of experience that can be produced with the tools of immersive media technologies.33 To develop consistently such three-dimensional auditory experiences, without remaining bound to principles of linear and frontal perceptual habits, is an immense challenge and has yet to be realized. The concept of soundscape offers various starting points for this and is also suitable as a point of departure for multimodal-environmental modeling in the field of virtual reality.

Author Biography

Prof. Sabine Breitsameter is an award winning author, producer, curator and festival director with four decades of practical experience in the international media industry and art institutions, with focus on media art. Since 2006 she researches and teaches at Darmstadt UAS as a professor for “Sound and Media Culture ” Co-founder of the Master’s program Sound Studies at the University of the Arts/Berlin, guest professor for Experimental Audiomedia from 2004-2008. Jury member of e.g. Prix Ars Electronica, German Audiobook Prize, ARD/ZDF Award Women + Media Technologies; appointed advisory member at German Music Council, and co-president of the Hessian Film- and Media Academy (hFMA).

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 31

Notes

1 Translation: John Jones. This text is an extended and updated version of my article “Soundscape,” Hansjakob Ziemer, Daniel Morat (Eds.), Handbuch Sound. Geschichte Begriffe Ansätze. (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler Verlag, 2018), 89-99.

2. Richard Buckminster Fuller, “The Music of the New Life,” Music Educators Journal, 52(6) (1966): 52.

3 cf. Michael Southworth, The Sonic Environments of Cities, Environment and Behaviour (1969): 49-70. The term soundscape is said to have appeared occasionally in Englishlanguage musicological as well as anthropological literature as early as the 1930s. Concrete research results on this are still pending.

4 R. Murray Schafer, The New Soundscape (Scarborough: Berandol Music Limited/New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1969).

5 Hildegard Westerkamp, “Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic Ecology.” Organised Sound, An International Journal of Music and Technology, Volume 7 “Soundscape Composition,” Number 1, Cambridge (2002): 51-56.

6 Murray Schafer in conversation with Klaus Schöning, on the ocassion of the premiere of his soundscape composition A Winter Diary on radio station WDR3 Studio Akustische Kunst, 17 April 1998.

7 Luigi Russolo, Manifesto futurista, Milan, 11 March 1913, cited in: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/quellentext/39/, (01.06.2023) in the translation by Justin Winkler and Albert Mayr.

8 Ibid.

9. Cf. Johannes Gabriel Granö, Pure Geography, A methodological study, enhanced by examples form Finland and Estonia (1929), edited by Olavi Granö and Anssi Paasi, translated by Malcolm Hicks (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).

10 R. Murray Schafer, Klang und Krach. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Hörens (The Tuning of the World in German translation), translated by Kurt Simon und Eberhard Rathgeb and Heiner Boehnke, eds. (Frankfurt/Main: Athenäum, 1991).

11 Justin Winkler, “Landschaft hören. Geographie und Umweltwahrnehmung im Forschungsfeld Klanglandschaft,” Regio Basiliensis. Basler Zeitschrift für Geographie 33, 1992, H. 3, pp. 196-206. Justin Winkler, Klanglandschaften: Untersuchungen zur Konstitution der klanglichen Umwelt in der Wahrnehmungskultur ländlicher Orte in der Schweiz, Universität Basel/Schweiz, 31 January 1995.

12 This was analyzed very effectively by Barry Truax, Acoustic Communication (Westport/London: Ablex Publishing, 1984): 12.

13 See also McLuhan’s concept of audio-tactile all-round perception of the electronic age in: Herbert Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy, The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962), 11 et seqq.

14. R. Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1977), 237 ff.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 32

15 https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/world-soundscape-project-emc (02.06.2023).

16. World Soundscape Project Recording Library: http://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studiowebdav/srs/index2.html (02.06.2023).

17 Sabine Breitsameter, Darren Copeland, Claude Schryer and Hans-Ulrich Werner.

18. Soundscape Vancouver 1976-1996. CD. Goethe Institute, Munich 1996.

19. Helmi Järviluoma et al. eds., Acoustic Environments in Change (Tampere: University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, Studies in Literature and Culture 14, 2009).

20 The musicologist Karl Traugott Goldbach attributes to the works of the composer Luc Ferrari the beginnings of an “ecological listening,” cf. ibid., “Acousmatic and Ecological Listening in Luc Ferrari’s Presque rien avec filles” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 3/1, 2006, 127-137.

21 For example, in his piece Presque Rien no. 1 Lever du jour au bord de la mer (1967). Recorded on the beach of Vela Luka, Croatia, the 21-minute piece consists of a condensation and deliberate arrangement of everyday sound episodes that Ferrari had recorded over the course of a single day.

22. Both were members of Schafers research team at Simon-Fraser-University, Burnaby (Canada).

23 Hildegard Westerkamp, Soundscape Composition: Linking Inner and Outer Worlds (Amsterdam 1999), https://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writingsby/?post_id=19&title=%E2%80% 8Bsoundscape-composition:-linking-inner-and-outer-worlds-

24 Ibid.

25 Hildegard Westerkamp, “Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic Ecology,” Organised Sound, An International Journal of Music and Technology, Volume 7, Number 1 (2002), 51–56.

26 Cf. Katherine Norman, “Real-World Music as Composed Listening,” Contemporary Music Review, 1996, Vol. 15, Part 1, 19.

27 See also Barry Truax: “Part of the composer’s intent may also be to enhance the listener’s awareness of environmental sound,” in ibid, Acoustic Communication (Westport/London: Ablex Publishing, 1984), 207.

28 Tim Ingold, “Against soundscape,” in E. Carlyle, ed., Autumn Leaves: Sound and the Environment. Artistic Practice (Paris: Double Entendre, 2007), 10-13. Stefan Helmreich refers to Ingold’s critique in “Listening against Soundscapes” Anthropology News, Boston, December 2010, 10.

29. R. Murray Schafer, Die Ordnung der Klänge. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Hörens, The Tuning of the World in its second German translation), updated, newly edited and translated by Sabine Breitsameter (Mainz-Berlin: Schott-International, 2010), 50.

30 Ibid.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 33

31. This connection had been emphasized by Schafer, and was elaborated by Barry Truax in his dynamic and interdependent model of “acoustic communication,” cf. ibid, Acoustic Communication (Westport/London: Ablex Publishing, 1984), 12.

32 Formative listening cf. Sabine Breitsameter, “Radiokunst innerhalb und ausserhalb der Schule,” in Jutta Wermke, ed., Medien im Deutschunterricht 2007 (Jahrbuch).

Thematic focus: Listening Aesthetics Listening Education (Munich: kopaed, 2010), 6474. See also ibid., “Methoden des Zuhörens. Zur Aneignung audiomedialer Produktionen”, Paragrana. Internationale Zeitschrift für Historische Anthropologie, FU Berlin, Band 16, 2007, Heft 2, 223-236.

33. Cf. Sabine Breitsameter, “Plastische Arbeit mit Klang. Grundlinien künstlerischer Forschungsarbeit am 3D-Audio-Lab der Hochschule Darmstadt,” Positionen. Texte zur aktuellen Musik, Heft 110, Mühlenbeck bei Berlin (2017), 53-62.

Bibliography

Breitsameter, Sabine. “Plastische Arbeit mit Klang. Grundlinien künstlerischer Forschungsarbeit am 3D-Audio-Lab der Hochschule Darmstadt.” Positionen. Texte zur aktuellen Musik, Heft 110, Mühlenbeck bei Berlin (2017), 53-62.

Breitsameter, Sabine. “Radiokunst innerhalb und ausserhalb der Schule.” In Medien im Deutschunterricht 2007 (Jahrbuch). Hörästhetik - Hörerziehung, edited by Jutta Wermke, 64-74. Munich: koepaed 2010.

Breitsameter, Sabine. “Methoden des Zuhörens. Zur Aneignung audiomedialer Produktionen.” Paragrana. Internationale Zeitschrift für Historische Anthropologie, FU Berlin, Band 16, 2007, Heft 2, 223-236.

Fuller, Richard Buckminster. “The Music of the New Life.” Music Educators Journal, 52(6) (1966) 52-60, 62, 64, 66-68.

Goldbach Karl Traugott. “Acousmatic and Ecological Listening in Luc Ferrari’s Presque rien avec filles.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 3/1, 2006, 127-137.

Granö, Johannes Gabriel. Pure Geography, A methodological study, enhanced by examples from Finland and Estonia (1929), edited by Olavi Grano and Anssi Paasi, translated by Malcolm Hicks. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Helmreich, Stefan. “Listening against Soundscapes.” Anthropology News, Boston, December 2010, 10.

Ingold, Tim. “Against soundscape.” In E. Carlyle (ed.), Autumn Leaves. Sound and the Environment. Artistic Practice, 10-13. Paris: Double Entendre, 2007.

Järviluoma, Helmi et al. eds. Acoustic Environments in Change. Tampere: University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, Studies in Literature and Culture 14, 2009.

McLuhan, Herbert Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy, The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 34

Norman Katherine. “Real-World Music as Composed Listening”. Contemporary Music Review, 1996, Vol. 15, Part 1, 1-27.

Russolo, Luigi, “Manifesto futurista, Milan, 11 March 1913.” Cited at: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/quellentext/39/, (01.06.2023) in the translation by Justin Winkler and Albert Mayr.

Southworth, Michael. “The Sonic Environments of Cities.” In Environment and Behaviour (1969) 49-70.

Schafer, R. Murray. The New Soundscape. Scarborough: Berandol Music Limited/New York: Associated Music Publishers, 1969.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Tuning of the World. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1977.

Schafer, R. Murray. Klang und Krach. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Hörens (The Tuning of the World in its first German translation), edited by Heiner Boehnke and translated by Kurt Simon und Eberhard Rathgeb. Frankfurt/Main: Athenäum, 1991.

Schafer, R. Murray. Die Ordnung der Klänge. Eine Kulturgeschichte des Hörens (The Tuning of the World in its second German translation), updated, newly edited and translated by Sabine Breitsameter. Mainz-Berlin: SchottInternational, 2010.

Soundscape Vancouver 1976-1996. CD. Goethe Institute, Munich, 1996.

Truax, Barry. Acoustic Communication. Westport/London: Ablex Publishing, 1984.

Westerkamp, Hildegard. Soundscape Composition: Linking Inner and Outer Worlds (Amsterdam 1999).

https://www.hildegardwesterkamp.ca/writings/writingsby/?post_id=19&title= %E2%80%8Bsoundscape-composition:-linking-inner-and-outer-worlds(02.06.2023).

Westerkamp, Hildegard. “Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic Ecology”. Organised Sound, An International Journal of Music and Technology, Volume 7 “Soundscape Composition”, Number 1, Cambridge (2002), 51-56.

Winkler, Justin. “Landschaft hören. Geographie und Umweltwahrnehmung im Forschungsfeld Klanglandschaft.” Regio Basiliensis. Basler Zeitschrift für Geographie 33, 1992, H. 3, 196-206.

Winkler, Justin, Klanglandschaften: Untersuchungen zur Konstitution der klanglichen Umwelt in der Wahrnehmungskultur ländlicher Orte in der Schweiz. Habilitation Treatise. Universität Basel/Schweiz, 31 January, 1995. World Soundscape Project Recording Library. http://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studiowebdav/srs/index2.html

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 35

Inspired by Nature

How Acoustic Ecology Informs the Work of Sound Scenographers

Ramon De Marco and Jascha Ivan Dormann

Abstract

Consciously designed soundscapes have the power to impart new meaning to visual content and fundamentally redefine the way we feel within spaces. Sound scenography is the art of staging spaces and settings using sound. As a discipline that developed out of conventional scenography, sound scenography primarily plays a role in exhibition scenarios such as museums or media installations, but is also used in businesses and public spaces As a collective specialized in sound scenography, Idee und Klang Audio Design creates auditive environments for these various settings. Sometimes we create our own artistic pieces, but we mostly create applied work for clients. Nonetheless, in our 18 years of existence, we have found that, more often than not, there is room to align our own views and beliefs with those of our projects to some degree. In this context, acoustic ecology, a discipline that studies the relationship between human beings and their environment, mediated through sound, is of great interest and importance to us. For one thing, it has profoundly impacted our approach to practicing sound scenography: some of the main principles of our work (namely how we deal with orientation, attention, association and spatial depth) are directly inspired by and derived from nature. For another thing, acoustic ecology has also found its way into various projects as a core topic. We live in a time in which no conversation is more pressing than the one about how to save what’s left of our planet’s rich natural environments. Here, acoustic ecology provides some brutally clear indicators, for example regarding the correlation between human behavior and species extinction. It shines a new light on the way our lifestyle negatively impacts both non-human species and our environment

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 37

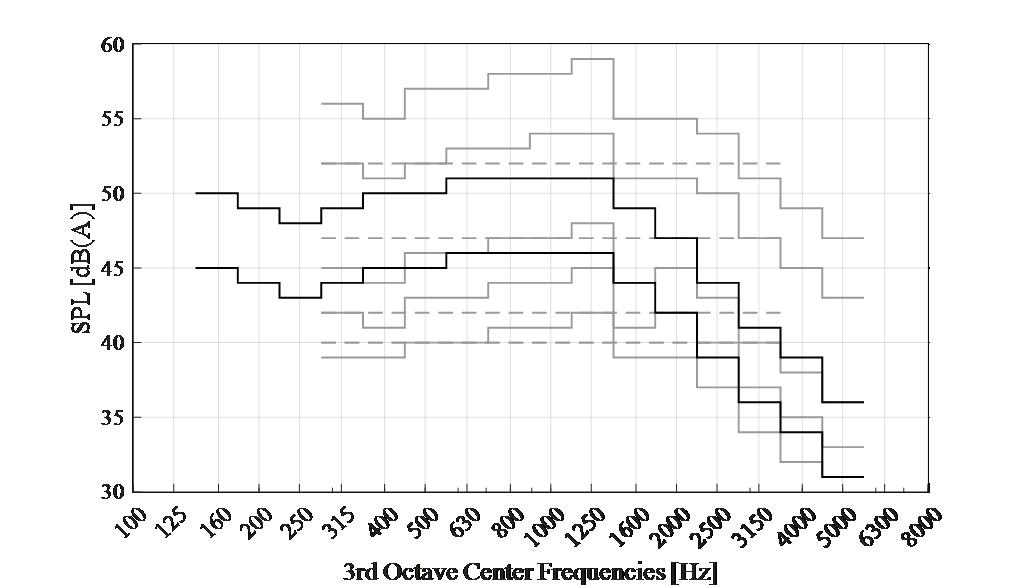

Introduction to Sound Scenography

Sound is incredibly underestimated and underused as a design medium. This is especially true in the field of exhibition design, where the auditory dimension has the potential to be a key element. This is where the relatively new discipline of sound scenography comes into play. Also known as acoustic scenography or audio scenography, this discipline is the science or art of applying sound in the design of rooms and environments. Sound scenography combines knowledge and insights from the fields of architecture, acoustics, communication, sound design and interaction design to convey artistic, historical, scientific, or commercial content while creating atmospheric moods. As a discipline, which is mostly seen as an extension to the field of “conventional” scenography, it is primarily applied in the contexts of exhibition design for museums, media installations and art However, it is also used for retail shops, theme parks, planetariums, spas, receptions, ticket halls, and open-plan office spaces.

The deliberate application of sound scenography can introduce an emotional dimension to rooms, exhibits and even individual interactions. It can create atmospheres and moods whose tonalities range from the realistic to the unreal or even the futuristic. It can evoke memories and associations. Soundscapes and sound accents also have the power to reinforce visual content or lend it entirely new meaning. Of course, content can also be conveyed entirely via sound without any connection to visual media. Furthermore, the purposeful design of the auditory dimension in spaces can also eliminate unwanted sounds or noises (via phenomena called absorption, sound masking and noise cancelling), or encourage visitors to act in a way that affects the aural sphere. For example, sound scenographers can create an auratic space in which visitors are encouraged to move around very mindfully and speak quietly with one another. Sound scenography uses the many strengths of sound and combines various auditory components to create a comprehensive transmedia experience.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 38

Can Architecture be Heard?

When we examine the relationship between sound and the environment it is being heard in, we find architecture at its very core. Sound might not be the first thing that comes to mind in the context of architecture, even though architecture provides the fundamental prerequisites for sound. Our perception of space and its dimensions, its shape, and its material properties is strongly informed by our sense of hearing. Only very few people, such as Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, or Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen, have realized this. They have studied the field and implemented projects following explicitly acoustic principles. Rasmussen asks:

Can architecture be heard? Most people would probably say that as architecture does not produce sound, it cannot be heard. But neither does it radiate light, and yet it can be seen. We see the light it reflects and thereby gain an impression of form and material. In the same way, we hear the sounds it reflects and they, too, give us an impression of form and material. Differently shaped rooms and different materials reverberate differently.

In architecture, acoustics are usually confined to the field of building acoustics, such as exterior sound insulation or impact sound insulation between two apartments. The aim is, for example, to prevent the sound of a razor being knocked out on the edge of the washbasin from disturbing people in the apartment below. Building acoustics are basically all about adhering to standards.

Room acoustics, on the other hand, influence the intensity and nature of sound reflection within a room and, as a consequence, its acoustic quality. Room acoustics thus operate at both levels: design as well as functionality. In practice, however, the focus is usually on the latter, and involves handling challenges like “how can we improve the speech intelligibility in our training rooms?” Only in special cases, such as the construction of a concert hall, do acoustics play a role in aesthetic design. Oftentimes, acousticians are only brought in when acoustic problems have been identified in an existing room. These types of belated acoustic renovations are usually expensive and often visually unsatisfactory. They could easily be avoided with smart design and the deliberate selection of materials at the planning stages.

Art Style | Art & Culture International Magazine 39