The following was written by Joshua for his collection of stories, Telling the Stories that Matter.

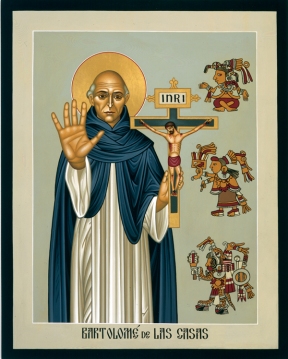

Bartolome de las Casas was born in Seville, Spain, in 1484  and so he was only nine years old when Christopher Columbus returned to Seville to tell of the world he had discovered to the west.Columbus had gained the favor of queen Isabella and king Ferdinand II by insisting that there was another route to the East Indies that didn’t involve traveling through Arabia but, instead, meant sailing west from Spain to approach the Indies from the other side. This interested the Spanish nobles because access to the East Indies, unencumbered by Italian and Arabian merchants and rulers, meant a lucrative trade in spices. In other words, the rich could get richer if Columbus was right. Columbus, of course, was wrong and had severely underestimated the circumference of the Earth but in his error he had stumbled upon the land we call the Americas. Bartolome wasfascinated by the tales of a distant land and different people and so he was thrilled when Columbus brought several of their men and women off of his ship and paraded them before the curious crowds. They came in chains and did so unwillingly but this fact was overlooked by those who were enchanted with dreams of foreign riches and conquest. When Columbus returned for his second voyage, Bartolome’s father and uncle went with him and Bartolome was left behind to imagine.

and so he was only nine years old when Christopher Columbus returned to Seville to tell of the world he had discovered to the west.Columbus had gained the favor of queen Isabella and king Ferdinand II by insisting that there was another route to the East Indies that didn’t involve traveling through Arabia but, instead, meant sailing west from Spain to approach the Indies from the other side. This interested the Spanish nobles because access to the East Indies, unencumbered by Italian and Arabian merchants and rulers, meant a lucrative trade in spices. In other words, the rich could get richer if Columbus was right. Columbus, of course, was wrong and had severely underestimated the circumference of the Earth but in his error he had stumbled upon the land we call the Americas. Bartolome wasfascinated by the tales of a distant land and different people and so he was thrilled when Columbus brought several of their men and women off of his ship and paraded them before the curious crowds. They came in chains and did so unwillingly but this fact was overlooked by those who were enchanted with dreams of foreign riches and conquest. When Columbus returned for his second voyage, Bartolome’s father and uncle went with him and Bartolome was left behind to imagine.

Bartolome’s father brought him a slave to be his servant and he developed a friendly relationship with the man. When Bartolome was eighteen, he went with his father and uncle to what we now know as Hispaniola aboard the ship captained by Nicolas de Ovando.Bartolome had spent years imagining that foreign land and it had become something mythical in his own imagination. Consequently, Bartolome was horrified to see the brutality and cruelty being perpetrated  against the people of the island by virtue of their different appearance and different language. The Spanish settlers were given land to which they had no legitimate claim and slaves with which to work their ill-gotten gains. Bartolome was uncomfortable with the savage approach the Spaniards were taking and, as a Dominican priest, began to wonder if this wasn’t a repudiation of Jesus’ way of love and mercy. Columbus was sending native peoples back to Spain as currency to repay his debts to the crown and wealthy financiers. Bartolome began to question the rightness of such barbarism. Bartolome began ministering to the native people in whatever little ways he could but it never seemed to be enough. Then, one day, Bartolome heard a Dominican priest named Antonio de Montesinos preach about the evil being committed against the people and being called “progress.” Antonio’s preaching–he was the first clergy member to vocally oppose the Spanish actions in the colonies–seemed to give Bartolome permission to join the fight for liberation and love.

against the people of the island by virtue of their different appearance and different language. The Spanish settlers were given land to which they had no legitimate claim and slaves with which to work their ill-gotten gains. Bartolome was uncomfortable with the savage approach the Spaniards were taking and, as a Dominican priest, began to wonder if this wasn’t a repudiation of Jesus’ way of love and mercy. Columbus was sending native peoples back to Spain as currency to repay his debts to the crown and wealthy financiers. Bartolome began to question the rightness of such barbarism. Bartolome began ministering to the native people in whatever little ways he could but it never seemed to be enough. Then, one day, Bartolome heard a Dominican priest named Antonio de Montesinos preach about the evil being committed against the people and being called “progress.” Antonio’s preaching–he was the first clergy member to vocally oppose the Spanish actions in the colonies–seemed to give Bartolome permission to join the fight for liberation and love.

Bartolome’s first decision was to free every slave on his settlement and to renounce the land he had been gifted. Having set an example of the way of the Kingdom of God he called upon other settlers to do the same, yet they refused and Bartolome was forced to travel back to Spain to seek reform. At his impassioned request he received permission to establish a settlement at Cumana in the northern portion of the region we call Venezuela. Bartolome imagined a settlement where native people and Spaniards would co-exist and help each other to live peacefully and comfortably. The problem, though, was the tension that had already developed between the Spaniards and the native people in the region. When Bartolome left the settlement, fighting would break out and people would die. Eventually, Bartolome left the settlement after Spanish raids took most of the native people as slaves and went to the Dominican monastery in Santo Domingo. From there he began to write accounts of the brutal murders of native people by Spaniards who claimed the yoke of Christ the Crucified. He lobbied Spain for laws that would protect the people upon whom they had intruded so much already. Meanwhile, he engaged in missionary work among native tribes and led many to place their faith in Jesus even though counter-arguments abounded in the colonists with whom they were acquainted. Though it meant defending himself against treason, Bartolome returned to Spain and was able to bring about new laws that abolished Columbus’ way of doling out land for support and slaves for loyalty. When Bartolome died in July of 1566 he was in Madrid but his heart still rested with the people he had learned to love in a distant and fantastic world.

and to renounce the land he had been gifted. Having set an example of the way of the Kingdom of God he called upon other settlers to do the same, yet they refused and Bartolome was forced to travel back to Spain to seek reform. At his impassioned request he received permission to establish a settlement at Cumana in the northern portion of the region we call Venezuela. Bartolome imagined a settlement where native people and Spaniards would co-exist and help each other to live peacefully and comfortably. The problem, though, was the tension that had already developed between the Spaniards and the native people in the region. When Bartolome left the settlement, fighting would break out and people would die. Eventually, Bartolome left the settlement after Spanish raids took most of the native people as slaves and went to the Dominican monastery in Santo Domingo. From there he began to write accounts of the brutal murders of native people by Spaniards who claimed the yoke of Christ the Crucified. He lobbied Spain for laws that would protect the people upon whom they had intruded so much already. Meanwhile, he engaged in missionary work among native tribes and led many to place their faith in Jesus even though counter-arguments abounded in the colonists with whom they were acquainted. Though it meant defending himself against treason, Bartolome returned to Spain and was able to bring about new laws that abolished Columbus’ way of doling out land for support and slaves for loyalty. When Bartolome died in July of 1566 he was in Madrid but his heart still rested with the people he had learned to love in a distant and fantastic world.