The ultimate end

“It doesn’t matter how badly they played,” said my old mentor, Dimitri, “if the symphony ends with a lot of loud, rousing brass, it will get a standing ovation.”

It is the end of a symphony, more than anything that has gone before, that leaves the most vivid impression on its audience. And I don’t mean the coda of the finale, but those last repeated chords that hammer home the end, those tonic, dominant, tonic, dominant tuttis that were so viciously lampooned by Eric Satie in his Embryons Deséchés.

Sometimes they never seem to be willing to give up and let you go home. Beethoven’s Fifth is the poster child for this cliche (not that it was a cliche when the composer first did it).

But ever since, the bringing home the tonic key and signing off a 45-minute symphony has been left to block chords pounding our ears.

There are exceptions, of course, and there are many examples of composers doing something interesting, surprising and creative with those end notes.

Here are my top five symphony conclusions:

Brahms, Symphony No. 2 in D, op. 73 — This is the symphony that Dimitri meant when he talked about rousing brass. No symphony comes close to the exciting, fresh, explosive yelling-it-out in ecstasy rah-rah that winds up this monument. It’s already loud and compelling when the trumpets, horns and winds sing out a quadruple-repeated and harmonized Nachschlag (turn) and do it again a third higher (first yellow arrow in the score). The audience is going “whoopee” and then the trombones and bass trombone hit and hold a D-major chord (which Brahms particularly marks fortissimo) over the staccato final chords of the rest of the orchestra, and finally resting on a tutti D. Wow. You always want to stand up and cheer at the end — which audiences habitually do.

Haydn, Symphony No. 45 in F-sharp, “Farewell” — Modern instruments can negotiate most keys fairly well, but in Haydn’s day, F-sharp was a pretty out-there key, which made this symphony strange sounding to begin with. There was an extra bite of instruments that could not quite play easily in key. This is the only symphony Haydn wrote in this orphan key. It is a “Sturm und Drang” symphony, full of sound and fury, accentuated by the odd key choice, but the finale ends in a whimper, not a bang. It is the opposite of the Brahms. In fact, Haydn has the instruments stop playing, one by one, and walk off the stage, leaving only two violins at the end playing a simple A-sharp below an F-sharp, as the concertmaster blows out the candle that would have illuminated his sheet music. A visually dramatic end, and a musically audacious feat.

Sibelius, Symphony No. 5 in E-flat, op. 82 — Silence is the astonishing surprise at the end of Sibelius’s Fifth, also, but loaded in between otherwise standard cadential chords. It was a really audacious thing to do — bring the symphony to a rousing climax and then stop everything for five beats, then hit another chord and wait again. Over and over at the end, with irregular silences between the bang-chords. If you count them, you can see the rests are oddly spaced, which gives the music a real off-balance feeling, like you cannot know what to expect. If you count out the rests in quarter-note time and the outbursts of tutti, you get: 1-2-Bang, 1-2-3-4-5-Bang, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-Bang, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-Bang, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-Bang, 1-2-3-Bang. (When he wrote the first draft of the symphony, those rests were filled in with noodling in the orchestra, the effect was bland, but he left these “black holes” there instead and blew the minds of his audience.)

Mahler, Symphony No. 9 — The last notes of Mahler’s final symphony, after 80 minutes of angst and rancor, are marked “ersterbend,” “dying.” The last two pages of the symphony take a full six minutes to play, attenuated and stretched to the limit of concentration by player and audience alike. They are orchestral whispers — death-bed speech as the music quietly accepts death. When played with the proper attitude, the audience greets the final silence not with applause, but with hush. In Amsterdam in 1995, when Claudio Abbado played it with the Berlin Philharmonic at the Mahler Festival, the audience stayed silent for several literal minutes before any applause, each member gazing into his or her own private abyss before coming back to reality and applauding the performance.

Shostakovich, Symphony No. 15 in A, op. 141 — This has to be one of the most peculiar symphonies in the repertoire, with its quotation of the Lone Ranger tune from Rossini’s William Tell in the first movement, and turning Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde into a waltz in the finale. But the final moments of the symphony are a complete enigma: Over a hushed pedal point in the violins, which goes on for two minutes, the percussion ding, snap and clang quietly in a mechanical tick-tock over and over, with xylophone, woodblock, castanets, glockenspiel, tympani, snare drum and triangle until a final C-sharp (the third of the tonic A-major chord) dings a final punctus, sounded on glockenspiel and celeste. What was Shostakovich thinking? He never explained. He smiled like the Cheshire cat.

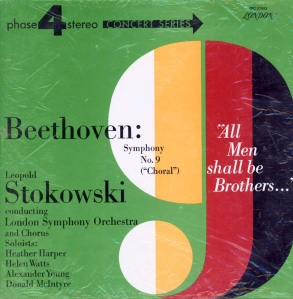

One last note — There is one symphony ending that has a surprising finish that you almost never  hear. It is buried under a welter of excited sound. When the chorus sings its final “Götterfunken” at the end of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the coda that follows builds up steam quickly and drives home to a final D major chord. It is in the final chords that Beethoven hides an extra fillip: He has his fiddles, which are already racing as fast as they can go, double the number of notes they have to play — dig-ga-dig-ga to diggadada–diggadada — and the tympani doubles its speed, too. This detail is usually buried in the overwhelming drive of the rest of the orchestra, but one recording makes the change clear: a 1967 recording by Leopold Stokowski and the London Symphony, originally released on a London Phase 4 LP, with singers Heather Harper, Helen Watts, Alexander Young and Donald McIntyre. Its drive is overwhelming.

hear. It is buried under a welter of excited sound. When the chorus sings its final “Götterfunken” at the end of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the coda that follows builds up steam quickly and drives home to a final D major chord. It is in the final chords that Beethoven hides an extra fillip: He has his fiddles, which are already racing as fast as they can go, double the number of notes they have to play — dig-ga-dig-ga to diggadada–diggadada — and the tympani doubles its speed, too. This detail is usually buried in the overwhelming drive of the rest of the orchestra, but one recording makes the change clear: a 1967 recording by Leopold Stokowski and the London Symphony, originally released on a London Phase 4 LP, with singers Heather Harper, Helen Watts, Alexander Young and Donald McIntyre. Its drive is overwhelming.

Când ştii că eşti acasă?

// event.2parale.ro/events/click?ad_type=product_store&aff_code=036a3f65e&campaign_unique=ca8f8ce30&unique=070afad5f

2016-02-16 0:49 GMT+02:00 Richard Nilsen :

> Richard Nilsen posted: ” “It doesn’t matter how badly they played,” said > my old mentor, Dimitri, “if the symphony ends with a lot of loud, rousing > brass, it will get a standing ovation.” It is the end of a symphony, more > than anything that has gone before, that leaves the ” >