In my two decades in the United States, I have not associated with any German clubs nor attended any folksy events like Oktoberfest, which for many Americans epitomizes German culture. Not for me. I am not even a beer drinker, as I described in a previous blog post.

I did become a member of the The German Society of Pennsylvania located in Philadelphia. Founded in 1764, it is the oldest German-American association in the US, and it served as a model for later German societies in other American cities. I am utterly charmed by the stately building on Spring Garden Street in Philadelphia to which The German Society of Pennsylvania relocated in 1888, and in particular by its library. Unfortunately I live too far away to take advantage of its cultural programs such as lectures, film screenings and concerts.

Walking into the Joseph P. Horner Memorial Library with its gallery, wooden glass-paneled bookcases and antique tables, chairs and reading lamps is like entering a time capsule. The library collection with its 50,000 mostly historic books, documents, journals and manuscripts is one of the largest collections of German books in the United States.

When I had the chance to spend an afternoon at the library, I went straight for the small cookbook collection. What interested me most were the German cookbooks published in America. But I got sidetracked quickly. As you can read in my piece for Monument Lab about a German pretzel monument for Philadelphia, I started browsing the legal statutes of the Social Support Association of the Philadelphia Bakers, founded in 1855, and the Golden Jubilee 50th Anniversary Edition of the Confectioners’ and Cake Bakers’ Beneficial Association of Philadelphia from 1922. These guilds and associations played an important role in the city because they also provided social services to members.

Another page that caught my attention in the Confectioners’ Association anniversary volume was an advertisement by a Philadelphia bank offering safe and fast money transfers to Germany. At that time Germany was shaken by instability and hyperinflation, the exchange rate between the dollar and the Mark was one trillion Marks to one dollar. “Do you know what it means to have a family and not being able to buy the most basic foods?,” the ad asks. “We Germans here are able to relieve their main worry by supporting them with money because money can buy anything.”

In the introduction to his German-American Illustrated Cookbook (in German) published in New York in 1888, author Charles Hellstern complains that “the existing cookbooks do not take into proper consideration the climate conditions and products available in America” whereas he tried with “utmost diligence to take what’s good in German cuisine while not neglecting the valuable of the cuisine here.” That’s exactly the point I have been making with my book Spoonfuls of Germany. Not too much has changed since then; many contemporary German cookbooks on the American market are still impractical, largely because they are written for the German, not the American home cook.

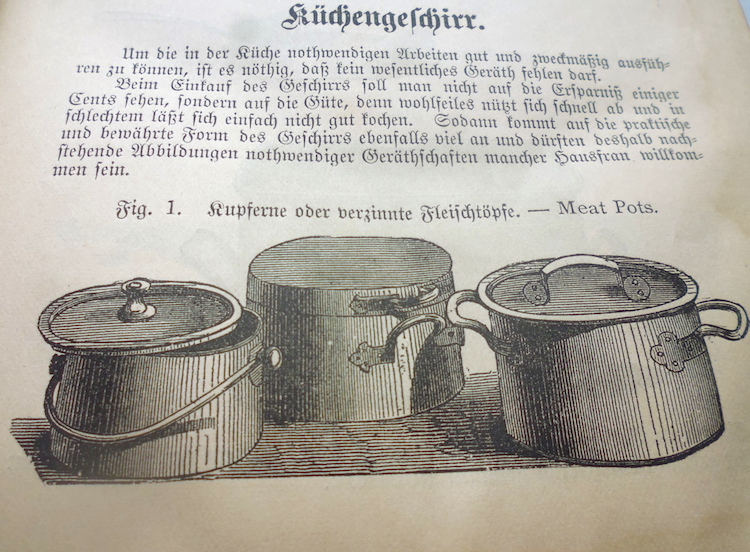

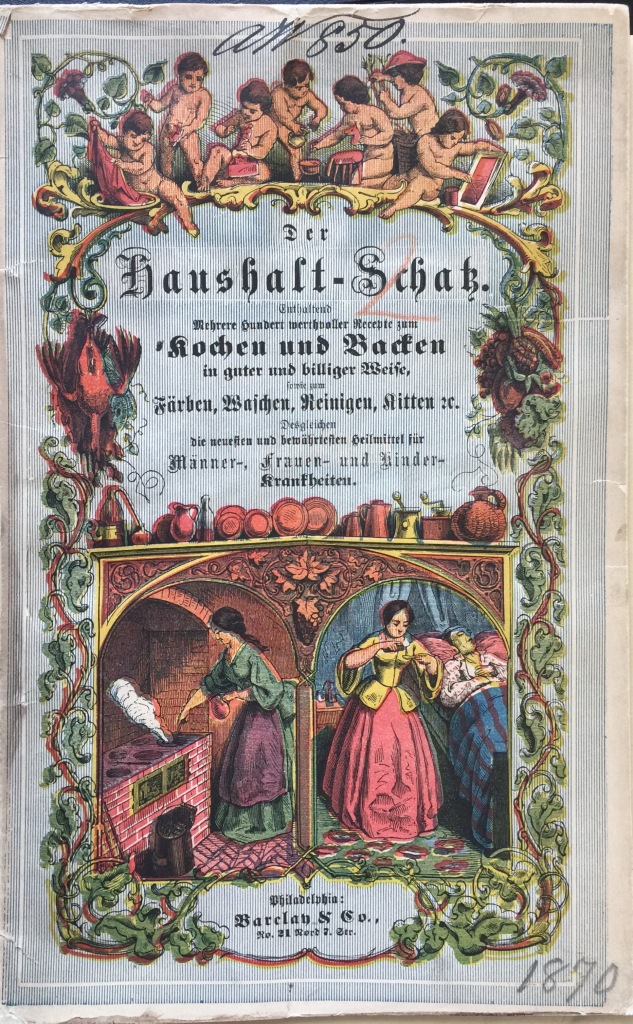

Bringing together the Old World and the New World, Hellstern’s book includes recipes for cornstarch cake, cranberry jelly, crabapples (which are virtually unknown in Germany to the present day), summer and winter squash (referring to them as Sommer-Kürbis and Winter-Kürbis, which is highly unusual in German and a real anglicism), and, very exotic even for America, maidenhair fern juice. You find dishes with hominy on the same page as a recipe for large German pancakes (Eierschmarren, aka Eierhaber). In his chapter about cookware Hellstern cautions housewives to put quality first instead of trying to save a few cents. I’d very much like to follow Hellstern’s guidance and buy copper pots but I am afraid the price difference to ordinary pots is more than a few cents nowadays! The United States Cook Book by William Vollmer, formerly “chef de cuisine of several of the first hotels in Europe, now steward of the Union Club in Philadelphia”, was published both as a German and English edition in 1870. For tomatoes, it happily mixes German and English, as in Gekochte Tomatos and Gebackene Tomatos. I assume the odd spelling of tomatoes is due to the fact that the tomato had not yet conquered Germany. Even in its later editions from the early 1900s, Henriette Davidis’ classic German cookbook does not include tomato recipes but the American edition of her book from 1879 already does, because tomatoes became mainstream with the Civil War when canned tomatoes were used to feed the Union army, and from then on became part of mainstream American cooking.

The United States Cook Book by William Vollmer, formerly “chef de cuisine of several of the first hotels in Europe, now steward of the Union Club in Philadelphia”, was published both as a German and English edition in 1870. For tomatoes, it happily mixes German and English, as in Gekochte Tomatos and Gebackene Tomatos. I assume the odd spelling of tomatoes is due to the fact that the tomato had not yet conquered Germany. Even in its later editions from the early 1900s, Henriette Davidis’ classic German cookbook does not include tomato recipes but the American edition of her book from 1879 already does, because tomatoes became mainstream with the Civil War when canned tomatoes were used to feed the Union army, and from then on became part of mainstream American cooking.

Another special item in the library collection is a handwritten recipe collection and memoir from 1914 by Ernestine Hochgesang Schaefer in German and English. It is intriguing simply in terms of the itinerary of the author. Born in 1829 in Moscow to a father from Bavaria and mother from a French noble family that had fled to Berlin during the French Revolution, Ernestine lost her mother when she was a toddler. The father moved the family back to Germany in 1832 and then to the United States in 1848. One year later Ernestine married Ernst Karl Schaefer, also a German immigrant. He started a bookstore, and in 1851 he joined his business with Rudolph Koradi to found the publishing firm Schaefer & Koradi. Schaefer’s brother Gustav Moritz Schäfer headed the main publishing house in Leipzig, Germany, while Schaefer & Koradi established itself as a leading Philadelphia German publishing house that released, among many other titles, William Vollmer’s cookbook.

After my brief poking around in the cookbook collection I can see how the Horner Library is a treasure trove for academic researchers in the field of German American studies. Heidi Voskuhl, who teaches history of technology at the University of Pennsylvania, recently did research at the library about German immigrant engineers around 1900. What she wrote afterwards about the library refers to engineers, engineering, and industrialization but I think it applies to many other areas as well – that “the Horner Library is a panorama (…) in the ongoing discussion about the place of German immigrants in Pennsylvania and the United States, and the place of German culture in American culture.”

I will certainly return to the library when I have the time to explore some other cookbooks.

March 5, 2018 at 3:00 am

What a fascinating insight!! I love old cookery books, and it’s interesting to see that some of the advice has often stood the test of time!! I agree with you on the cooper saucepans, they are just a little too expensive (and also a bit too heavy), but it’s never a good idea to buy cheap things for the kitchen. I hope you’ll be able to get back to Philadelphia before too long!!

March 7, 2018 at 3:12 pm

Thanks for posting this I will definitely when I’m there in July. I’m a none beer drinking German as well. There are a number of us, we should form a club.

April 12, 2018 at 10:39 pm

Have you been to pretzel park in manayunk

April 27, 2018 at 9:33 am

Linda, No, I haven’t and I had not even heard about it until you asked. I will check it out on my next visit to Philadelphia. Thanks!