Sergio Oliva was “The Myth.” It’s the greatest nickname in all of bodybuilding. Not only was his physique mythically proportioned—so far ahead of its time it can still seem unreal today—but the man, too, was an enigma—a fiery Cuban refugee who dominated bodybuilding like no one before, who then dueled with Arnold Schwarzenegger before virtually vanishing during what could’ve been his peak decade, working menial jobs and then patrolling Chicago’s streets. He was nearly killed by his wife and had a contentious relationship with the son who bears his name and who followed in his giant footsteps. This is the full story of Sergio Oliva, The Myth and the man.

ESCAPE FROM CUBA

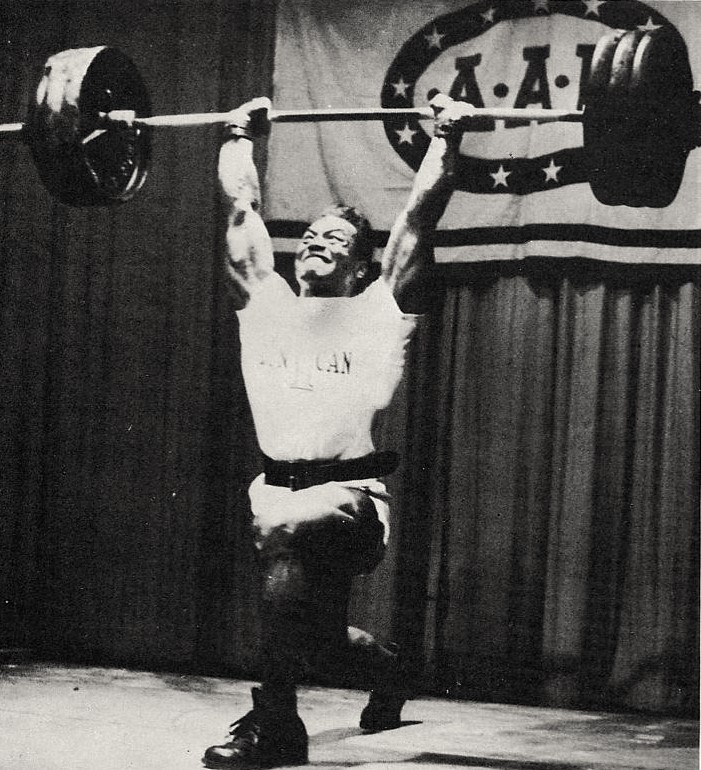

Sergio Oliva was born on the fourth of July in 1941 in a small city on the western edge of Cuba. As a child, he worked with his father in the cane fields. To fight communism, he joined the army when barely 16. Two years later, communism won. The ex-soldier schemed ways of fleeing Castro’s Cuba for Miami, but he was too frightened to join others on a crowded boat. He’d have to find another way. Fatefully, the manager of Cuba’s weightlifting team noticed Oliva’s physique—muscled from hard labor—on a beach, and encouraged him to take up weightlifting. From the start, Oliva excelled, winning titles and setting national records. With a delegation, he was sent to the Marxist motherland, Russia, to train for three months. Afterwards, Oliva was Cuba’s top 198-pound (90 kg.) weightlifter, representing his country at the 1962 Central America and Caribbean Games in Kingston, Jamaica, when he snuck out of the team quarters and ran to the American consulate. Behind him were other members of the Cuban team.

Sergio Oliva remembered it this way: “So when I take off, I am the first one running, and in those days the embassy had two Marines outside, and I was coming like a torpedo. As I ran and picked up speed, a wheelbarrow of mangoes came from nowhere. I jumped this and then jumped a large fence. Then I approached the door of the embassy with the two Marines outside of it. I would have taken both with me if they had tried to stop me. So they opened the door and I went through. But right after me there were many of the delegation trying to escape and about half of them escaped. And everyone came right after me, and we had gotten inside the American Embassy, and they were screaming and crying and jumping, and we cannot believe it. Everyone was shouting and jumping and embracing each other, even Castro’s secret police. What are we going to do now? So right away [the Americans] call Washington, and they say we have got a problem. They are going to send a small plane and take all of us to Miami Florida. And this is how we came to the United States.”

CHICAGO HOPE

In America, in Miami, Oliva worked as a TV repairman, before moving to Chicago in 1963. He knew virtually nothing about the Midwest metropolis, and he was warned about its frigid winters, but he liked the name. There, he worked at a foundry, and he trained at Chicago’s Duncan YMCA, celebrated for its musclemen. “But I was working 12 to 14 hours a day there and then go to the gym,” Oliva remembered. “I got up at six o’clock in the morning, go to work, then have to work a lot of hours because the more I work, the more money I get. So when I got off at six or seven o’clock, then I was going to the YMCA and do my exercise for three to four hours every day. When I was finished with that, I had to go home and cook for myself because I was not able to deal with restaurants and things like that. [He spoke almost no English.] So by the time I eat, that was it—time to go to bed.”

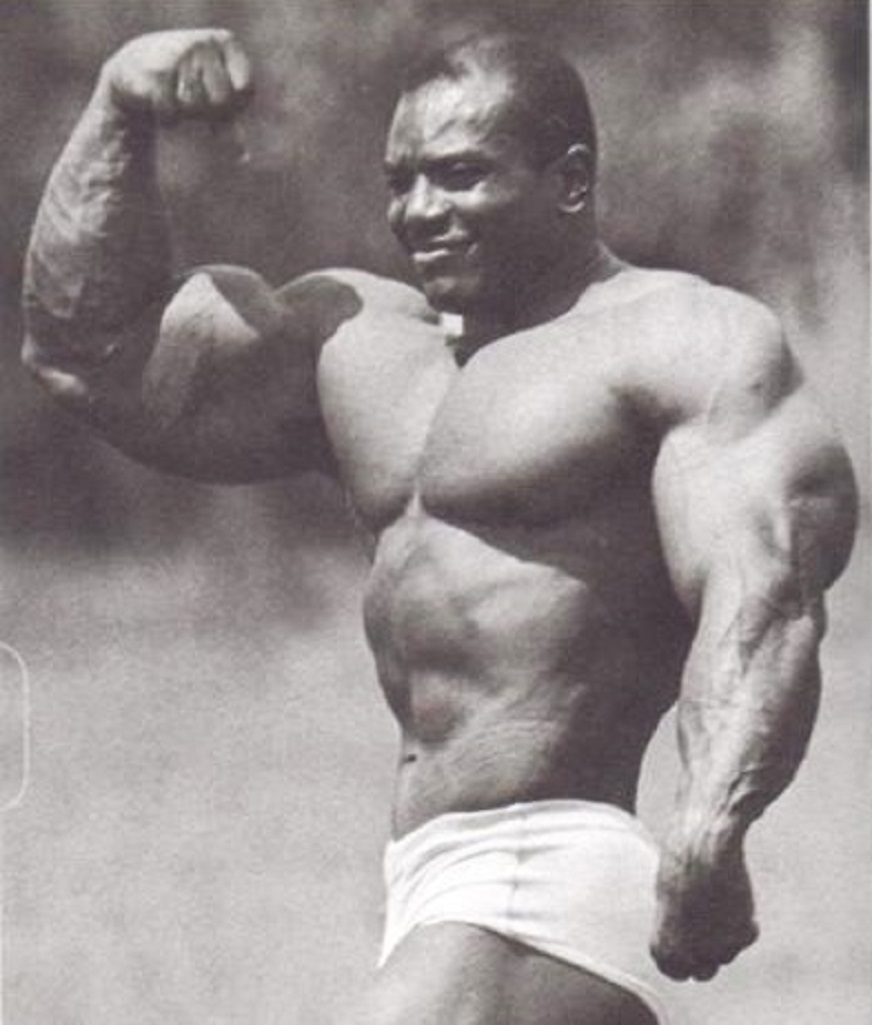

His tremendous strength as well as his quickly expanding physique attracted attention in the small world of Midwestern muscle. Encouraged by bodybuilder Bob Gadja, who ran the Duncan YMCA, Oliva took up Gadja’s high-volume training system PHA (peripheral heart action), which included circuits, supersets, and a focus on the muscle pump. For protein, he drank a gallon of milk daily. And Oliva began competing in bodybuilding, winning his debut contest, the Mr. Chicagoland, in 1963. The following year, he won the Mr. Illinois and entered the AAU Mr. America, finishing seventh in what was then America’s top bodybuilding contest.

MR. AMERICA?

In 1965, despite winning the most muscular award, Sergio Oliva was fourth in the AAU Mr. America; his friend Gadja, who was white, was second.

In 1966, Oliva was a very controversial second in the Mr. America and again won the most muscular award; Gadja won. The Cuban immigrant had earlier defeated Gadja at the Jr. Mr. America. No Black man had ever won the AAU Mr. America (the first to do so would be Chris Dickerson in 1970, its 33rd rendition). The stated reason for Oliva’s loss despite possessing what was clearly the best body was supposedly his inability to speak much English. But Oliva believed, like many, that it was more about the color of his skin.

“So we know that, but it was so obvious,” Oliva later said of the racism that kept him from the title. “Listen to this: I won the best legs, the best abdominals, the best chest, the best back, and the best arms, and the most muscular man. What else is left? How can they say I am in second place? It was a joke, but I went to my friend, Bob Gajda, a very honest man, and he said, ‘This is not right.’ I said, ‘Forget it; they said you won it and you won it. Whatever has happened we are still friends.’ I really don’t feel bad at all, because deep inside of me I know I didn’t lose.”

The AAU may have been the top American bodybuilding organization then, but it had competition from the Weider brothers’ upstart IFBB. Four months after June’s AAU Mr. America, Sergio Oliva journeyed to New York City for the IFBB Mr. World. A report of that contest, noted that applause rocked the Brooklyn Academy of Music when Oliva sauntered to center stage: “And this was his contest, winning it without a battle.”

Held as part of the same collection of contests on that same day, was the second Mr. Olympia contest. As the newly crowned Mr. World, Oliva entered the Olympia. The reporter noted: “Sergio is massive and possesses ideal proportions that are defined to their limit. Recognized as one of the world’s all-time greats, he is just beginning his career as an IFBB champ.” Indeed. At 25, the Cuban refugee was already the heir apparent when Larry Scott announced his retirement from the Olympia stage. The man who would soon become a myth would not lose again that decade.

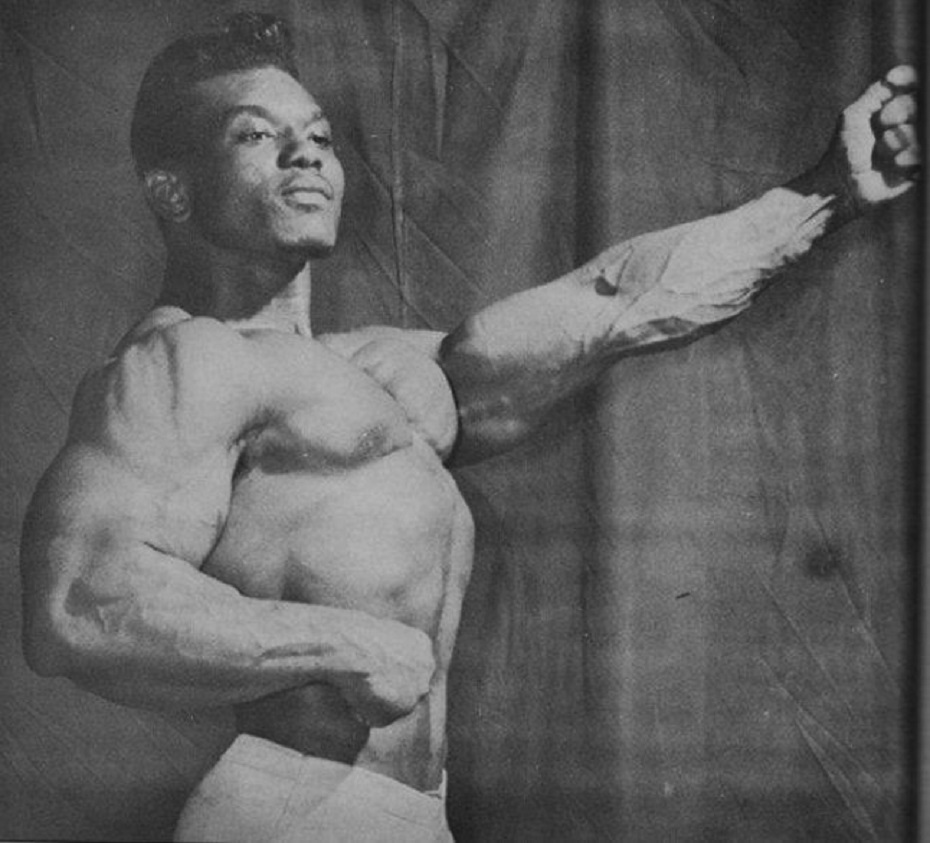

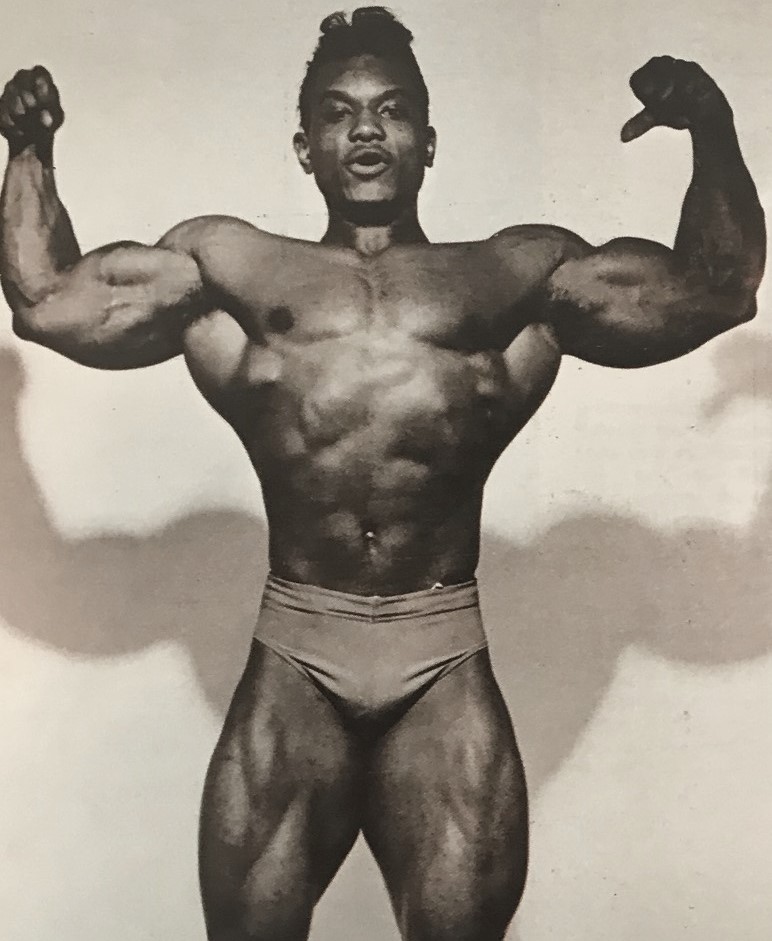

SERGIO OLIVA BECOMES THE MYTH

After winning the IFBB Mr. Universe (staged in Montreal) earlier in the year, Sergio Oliva showed up at the 1967 Mr. Olympia with a phenomenal new body. At 5’10” and around 225 pounds, he simply overpowered everyone else with his stupendous size: the ham-like arms, the dense pecs and delts, the wing-like lats, the columnar legs, and all built around an impossibly slim waist and hip structure. An observer tried to make sense of what he witnessed: “Some may object to him as ‘freakish’ but that’s because he’s so far ahead of the average bodybuilder.” Yes, Sergio Oliva was bodybuilding’s initial freak, the first to possess a modern level of size. There is the pre-Sergio era of Steve Reeves and Reg Park and the post-Sergio era of Arnold Schwarzenegger and later Dorian Yates and Ronnie Coleman and Big Ramy. Sergio marked the change, and nothing would be the same. At the 1967 Mr. Olympia, he romped to an easy victory. Never mind that he was yet to appear on a muscle magazine cover or that he would continue working menial jobs in Chicago—from the swelter of a foundry to the frigidity of a meat-packing plant. Never mind. Sergio Oliva was the world’s best bodybuilder.

“Somehow it had to be something to do with my bone structure, genes and many other factors and when I put it all together and trained the way I did…it was not easy. I trained brutal all my life. It was like an explosion, and I was growing like a balloon. Boom, boom, boom, like crazy,” Oliva remembered. “When I was standing in front of the mirror, when I was pumped and putting the baby oil on and everything [prior to going onstage in a bodybuilding contest] that was the only time I saw myself. And it was, ‘Oh my God, you really did it.'”

Writer and bodybuilder Rick Wayne wrote of the impression his fellow Caribbean made off stages: “Massive gold bracelets and chains rattled from his wrist and neck. The short sleeves of his custom-built shirts were split from the bottom of his deltoids down to his elbows, as if to allow his enormous triceps breathing space. His waist measured all of 29 inches, precisely the circumference of his thighs, which threatened the soft fabric of high-wasted pants every time Sergio sat down. His shoulders seemed a good six inches wider than the largest reclining chair. His calves measured close to 20 inches!”

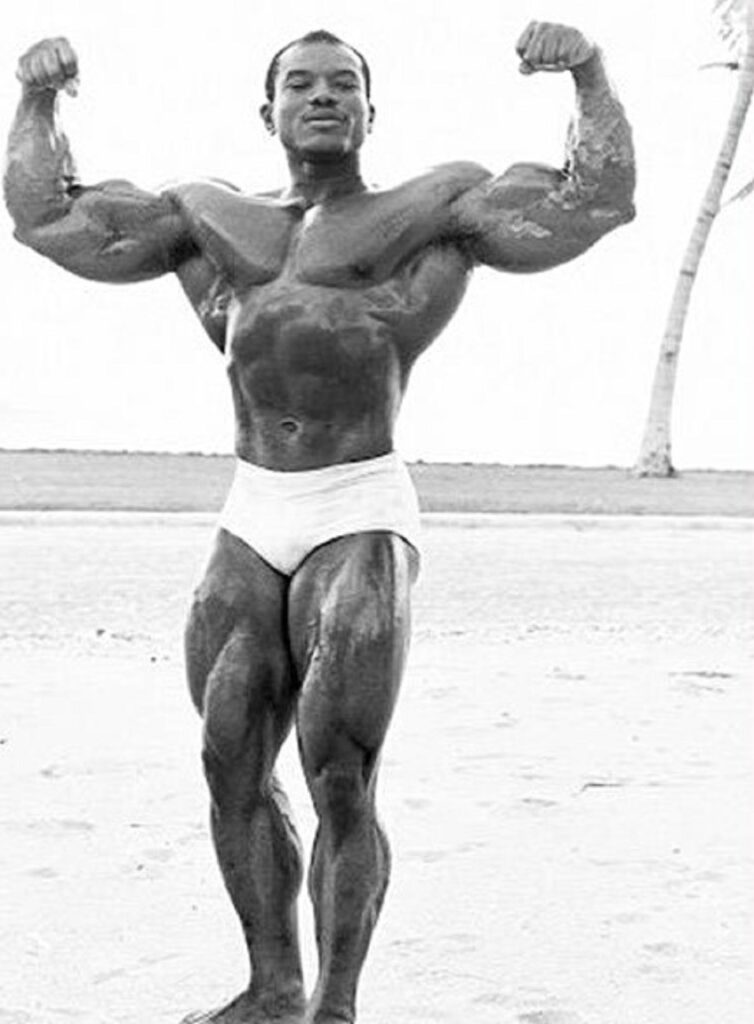

Sergio Oliva was so far ahead of the competition that no one even bothered to challenge him in 1968. He won the Mr. Olympia unopposed. An observer wrote: “So fantastic was his development that in just a few moments the others were forgotten, and everyone was caught up in yelling and pounding on the floor for more…more…MORE Sergio—without question, the greatest bodybuilder in the world.”

And in 1969, only the Austrian upstart Arnold Schwarzenegger dared to duel with The Myth. In his first autobiography, Arnold recalled his initial site of Oliva backstage: “I entered the dressing room the way I had been going in everyplace lately, like I was just taking over. It was as jarring as if I’d walked into a wall. He destroyed me. He was so huge, he was so fantastic, there was no way I could even think of beating him. I admitted my defeat and felt some of my pump go away. I tried. But I’d been so taken back by my first sight of Sergio Oliva that I think I settled for second place before we walked out on stage.” Oliva won again. He was then a three-time Mr. Olympia and regarded by many as the greatest bodybuilder who ever lived.

ARNOLD VS. SERGIO

The first years of the ’70s would be much different for Sergio Oliva than the final years of ’60s. Expecting an easy victory, he showed up over-confident and under-conditioned at the 1970 Mr. World in Columbus, Ohio, and lost to a surprise entrant, Arnold Schwarzenegger. Just like that, his aura of invincibility was punctured. Two weeks later, he lost again to Arnold at the Mr. Olympia. This set up 1971 as the rematch, but after Oliva competed in the NABBA Pro Mr. Universe (and lost to Bill Pearl) in London, he was banned by the IFBB from competing in the Mr. Olympia in Paris right afterwards. Arnold won again, unopposed, while Oliva merely guest-posed in the event.

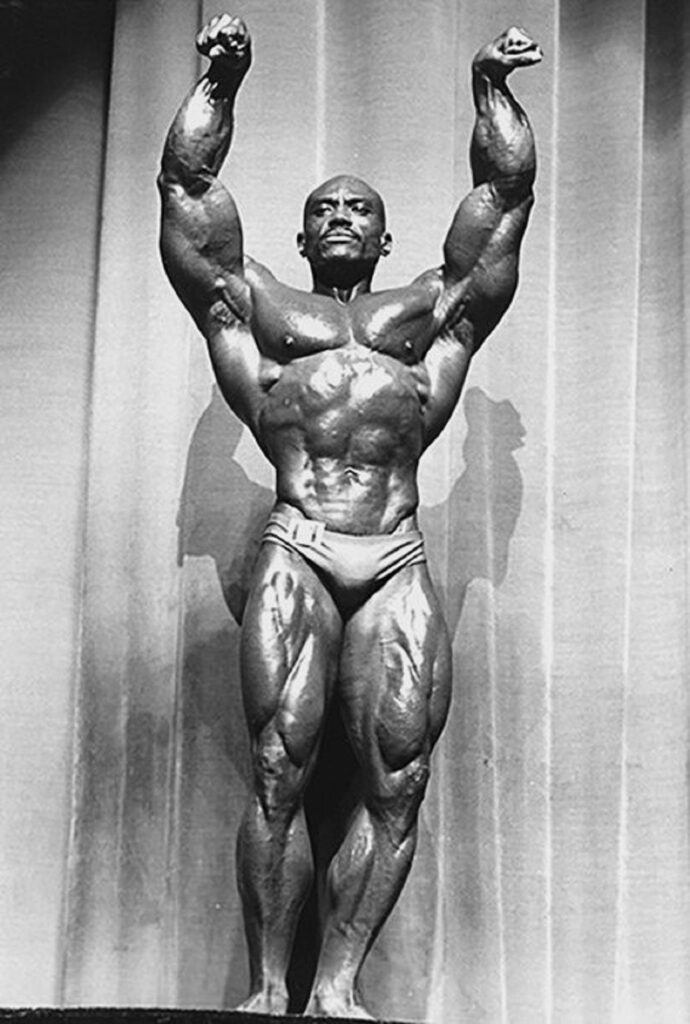

In 1972, the Olympia delivered, with not just another duel (the fourth and final) between Sergio and Arnold, but a lineup that included three additional future legends: Franco Columbu, Frank Zane, and Serge Nubret. As part of its “Nobody Remembers Who Came Second” campaign, a 2002 VISA commercial featured Sergio Oliva living the very ordinary life of a Chicago policeman. Text near the end states: “Runner-up, Mr. Olympia 1972. To Arnold Schwarzenegger.” To bodybuilding fans, the ad rang hollow. They remembered The Myth, and they did so foremost because of that 1972 Olympia, one of the most hotly debated bodybuilding contests. Both legends were at or near their best. At around 240 pounds, with fuller legs and a slimmer middle, many contend Sergio was the superior muscleman on that fateful day in Essen, Germany. The judges disagreed. The contest is still celebrated for what once was and for what could’ve been.

In all of bodybuilding’s long and rich history there is no pose more associated with one person than Sergio Oliva’s victory pose. It’s his and his alone. Standing tall and straight with colossal arms overhead, fists balled and turned outward, and lats flaring above his wispy waist, his upper body formed a “V” for victory atop a base of abundant legs. His rendition at the ’72 Olympia is perhaps bodybuilding’s most indelible image. The victory pose is so synonymous with The Myth and so difficult for even the best bodybuilders to pull off that few have even attempted it. You need ludicrously full arm muscle bellies with correspondingly stupendous biceps, triceps, and forearm development, but also a striking V-taper featuring broad clavicles and lats above minuscule hips. Throw in curvaceous legs, as well. That singular combination of classical structure, modern mass, and muscles that seem too long for their bones is what made Sergio Oliva “The Myth.”

THE LOST YEARS

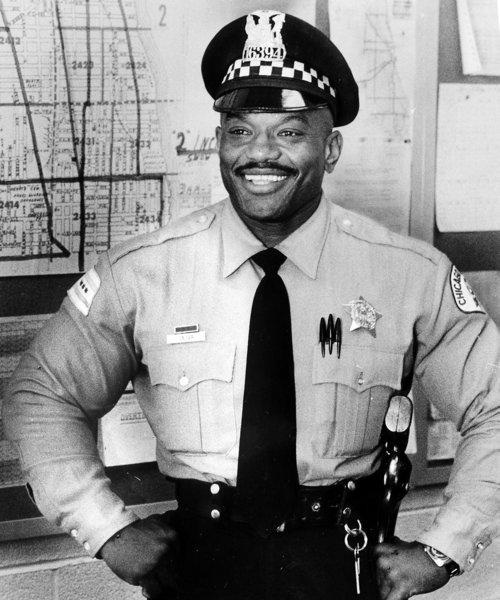

The next year, the volatile Cuban-American angrily challenged Arnold to an impromptu posedown at another contest. Then he angrily challenged him to an impromptu weightlifting competition when both appeared on a late-night TV show. Arnold cooly declined both, and he instead went on to win the next three Mr. Olympias while his nemesis was elsewhere. Sergio Oliva became a Chicago police officer in 1976 and patrolled the city streets in his specially tailored uniform. And, despite never doing much dieting, he collected inferior titles in inferior bodybuilding organizations: eight out of eight between 1974 and 1981, sometimes winning unopposed. And sometimes winning despite being buttery smooth, as when he was deemed superior to fellow legends Serge Nubret and Robby Robinson in ’81 at something called the WABBA World Cup. It hardly mattered. The Olympia was everything. Those years it was as if LeBron James had forsaken the NBA mid-career to ball in Turkey.

“Whoever invited me to go, I would go and compete,” Oliva recalled. “I did not belong to anybody. They called me the Cuban Rebel, but listen to this: Nobody made me except my Lord. I made myself, and I put everything together myself.” It was hard to even see photos from those contests, which weren’t covered in the major American muscle magazines, but, if you did, The Myth still looked as colossal as ever, but, as he barely bothered to diet and did no cardio, he was blurry at best. He turned 40 in 1981, and he’d lost most of a decade when he should’ve been at his peak and could’ve kept challenging Arnold and immortalized in Pumping Iron and probably winning more Olympia titles. Could he, with modern conditioning, have won all six Mr. Olympias from 1976 to 1981? What could’ve been?

THE COMEBACK

It seemed all 5000 fans in the Felt Forum of Madison Square Garden were on the verge of rioting, so great was their disapproval of the decision. The 1984 Mr. Olympia is now best remembered for Lee Haney winning the first of his record eight Sandow trophies. That announcement generated only cheers. The jeers came earlier, when 43-year-old Sergio Oliva, the three-time Mr. Olympia, was awarded eighth. The decision was just. Oliva’s middle-aged legs were somewhat downsized, and he couldn’t match the fine detailing of the top finishers, despite stringently dieting for the first time in his career. But fans didn’t want to consider The Myth a mere mortal.

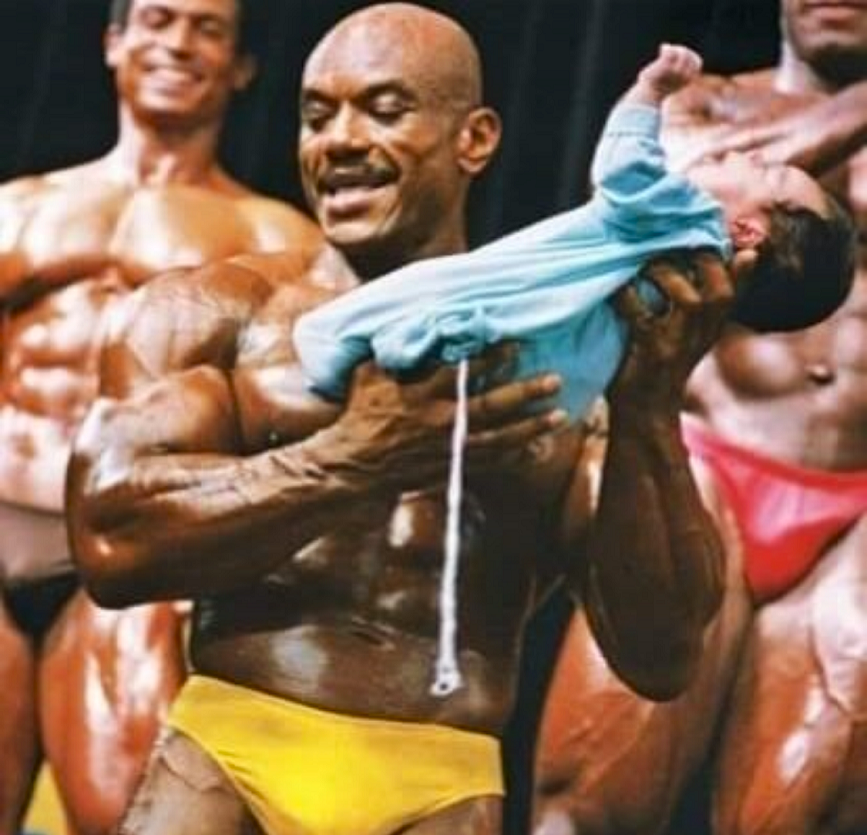

Because Oliva had a well-deserved reputation for a short fuse, FLEX magazine’s editor-in-chief Rick Wayne headed to the stage to urge his friend to stay calm. It had been a 12-year journey back to the Olympia and the good graces of the IFBB, so Wayne wanted to make certain the beloved legend didn’t blow it in a fit of rage. Wayne encountered Oliva’s wife, Arlene, who held two-week-old Sergio, Jr. She gave Wayne the baby, and he passed Junior to Senior. The crowd was awed into silence as the colossal icon, holding his tiny namesake, approached the podium. In his heavily accented English, Oliva gave a proud but gracious speech. Its most rousing moment was when he stated, “It no matter what happen tonight—eighth, seventeen, or twentieth—I forever be The Myth. And I hold in my arm Sergio, Jr., the next Myth.” The crowd roared.

The next year at the Mr. Olympia, 45-year-old Oliva was again eighth in his final bodybuilding contest.

BURDENS AND BLESSINGS

She called it self-defense, he called it an accident. Arlene Oliva shot Sergio Oliva five times in the summer of 1986. The bullets effectively ended The Myth’s bodybuilding career and his marriage. Sergio Oliva continued to work as a Chicago police officer until 2003. He traveled, doing seminars. Many Saturday nights were spent dancing to Latin music. For big anniversaries, he returned to the Mr. Olympia, reunited with the few in bodybuilding’s most exclusive club: Olympia winners. “Being Mr. Olympia carried a magic completely different from that associated with other titles,” he said in 1995. “I feel good still being known as Mr. Olympia. You stand apart.” He more frequently attended the Arnold Classic, signing autographs at the expo of the event named for the other half of bodybuilding’s greatest rivalry.

The junior Sergio and his sister Julia moved to Alabama with their mother, Arlene (a bodybuilder and personal trainer), but they spent time through the years with their father in Chicago. Having escaped poverty and repression in Cuba, Senior wanted Junior to excel in school and be a doctor or lawyer, not a bodybuilder. That’s why he refused to let the skinny, 145-pound teenager even go to the gym with him. So, Jr. trained on his own, packing on 30 pounds in his first three months. The Sergios clashed. “Our relationship got really rough once I got serious about bodybuilding a few years ago,” Junior said in 2007. “But it’s tough to get recognition from him for anything I do. He’s not much on praise.”

Though he was only a middleweight, if you squinted at the second Sergio Oliva when he stepped on stage for the first time in 2006, you could see some of the Mythical contours. Two years later, he was a heavyweight. Because of his name, recognition came easily. Titles didn’t come at all. And then came the backlash. Keyboard critics stopped focusing on structural similarities and fixated instead on all the ways the son didn’t measure up. “It’s a burden,” Junior said of his legendary name. “Not a blessing. No one wants to be measured against any of the Mr. Olympias, especially when you’re just an amateur. How can you live up to that?”

That legend, Sergio Oliva, was the first Mr. Olympia to die. The three-time Mr. O had been on kidney dialysis and in deteriorating health for months before perishing at 71 on November 12, 2012.

Three years later, the day after his 31st birthday, Sergio Oliva, Jr., won the NPC Nationals super-heavy class and overall (his first title). Forty-nine years after The Myth was denied the Mr. America, his son earned the title which supplanted the Mr. A. “I don’t know what he would’ve thought of my success,” the son said afterwards. “I don’t know that he would’ve cared at all.” Sergio Oliva, Jr. went on to win his professional bodybuilding debut in 2017, but has so far failed to notch a second pro victory.

THE MYTH, FOREVER

Ronnie Coleman’s reign was coming to a close, when Sergio Oliva averred: “A lot of people said I came 30 years too soon. I don’t believe that because God sets the time and place for you, not you. And who knows where I would come these days? Because in those days I was like that, these days I might be 400 pounds and ripped!” Anything seemed possible with Sergio Oliva’s phenomenal DNA, the unparalleled ability to pack muscle onto the perfect structure. The interviewer asked him if his was the best physique of all time. “Oh, it’s hard to say because time changes.” He paused, contemplating. “But it was good. I just put it this way: I was good, too good for them to try to put me on the side, which was impossible to do. There was just too much.”

There was indeed just too much—the impossibly full muscles, the miniscule waist, the dense flesh everywhere, some earned on weightlifting platforms, some in the heat of a foundry and the cold of a meat-packing plant, most in the basement weight room of a YMCA in this Cuban refugee’s adopted home of Chicago. Best of all time? Most blessed of all time? Standards change, but one thing is certain: Sergio Oliva was and forever will be The Myth.

A.I. ranked Sergio Oliva as the seventh best bodybuilder of all time. Check out the full list here.