Last night I finally managed to see the movie “Gravity”, which proves to me incontrovertibly that humans are not meant to stick their noses outside the protective layer of Earth’s atmosphere, despite having developed all kinds of high tech space gear (which, incidentally, seemed to have been designed primarily to kill Sandra Bullock’s character.) But this unexpectedly beautiful movie also made me think of a certain creature, whose amazing survival skills had lead NASA to use it to test the limits of life’s perseverance in outer space, long before somebody finally realized that people floating aimlessly in the cosmic void make for much better television.

As the first sunny days of March begin to melt away frozen remainders of winter in the northeaster United States, members of an ancient lineage of animals are getting ready to spring back to life. Throughout most of the year their habitat was as dry as a bone, but when the last patches of snow turned into water, leaf-packed depressions on the forest floor suddenly transformed into small, ephemeral ponds. Known as vernal pools, these fleeting bodies of water will be gone again by the time summer comes, but for now they create a unique aquatic ecosystem. Soon, the water is filled with thousands of tiny animals, at first not much larger than the point at the end of this sentence, but within a few weeks reaching the length of nearly a half of a pinky finger. They are the fairy shrimp (Eubranchipus vernalis), members of a group of crustaceans known as branchiopods, animals that were already present in the Cambrian seas half a billion years ago, before any plants even considered leaving water for terrestrial habitats.

Looking at the delicate, soft body of a fairy shrimp it is hard to imagine how a lineage of organisms so seemingly fragile could have survived for so long. Take one out of the water, and it is dead within seconds. Let the oxygen level in the pond drop, and the entire population is wiped out. Given a chance, a single fish could probably do away with them all in a day, but luckily fish don’t do well in ponds that last for only a few months of a year. But fairy shrimps’ frailty is an illusion because where it counts they are as tough as nails.

If you live in a place as transient as a vernal pool, here now but gone in a few months, an environment of unpredictable duration and often uncertain arrival, you better have a solid survival strategy to build your life around. First, once the right environment appears, you must develop very quickly and reach reproductive maturity before the changing conditions kill you. Second, you need a method to keep your genetic line alive, even when the only habitat in which you can survive is gone. And third, plan for the unforeseeable cataclysms, such as sudden evaporation of the pool before you are ready to produce a new generation. Because, if you fail on any of these accounts, your species will not last past the first generation. Fairy shrimp, despite their unassuming physique, are master survivalists in the most hostile and unstable of habitats, and execute the three-step action plan flawlessly.

As soon as the vernal pool forms, cysts containing fully formed shrimp embryos from the year before break open, and minute, swimming larvae emerge. They immediately start feeding on microscopic algae and bacteria already present in the water, and grow like crazy. During the first few days of their lives, baby fairy shrimp, known as nauplii, increase their length by a third and nearly double their weight every day. In about a month the animals are fully grown. One pair of the males’ antennae develops into giant, antler-like projections that help them catch and grasp their mating partners, while females grow big egg pouches on their abdomens. A few days later females start to lay at the bottom of the pool large clutches of cysts, eggs with embryos already developing inside, and die shortly after. Soon the water level in the pool begins to drop, and by June all traces of the once vibrant aquatic habitat are usually gone.

But inside the cysts hidden under a thin layer of soil the embryos are very much alive. They slowly continue their development, but can remain in the dormant state, out of the water, baking in the sun or being frozen in ice, for many years. Their outer shell is nearly waterproof, and quite sticky. This stickiness explains the sudden appearance of fairy shrimp in the most unexpected places, including old tires filled with water, after hitching a ride on the legs of birds and other animals. These cysts can live through being dipped in boiling water and liquid air (-194.35 °C, or -317.83°F), which is one of the reasons why these organisms are being used by NASA to test the survival of life outside of Earth’s atmosphere.

The following spring, if everything goes as planned, water of the melting snow awakens the dormant embryos, and within a few days they break the shell of their tiny survival capsules. But not all of them. Only a portion of the cysts responds to the first appearance of water, while others continue their slumber. If the pool dries prematurely, as it sometimes happens during a particularly warm spring, all early hatchlings die, and a second batch of larvae will emerge only if the pool fills up with water again. It has been shown that some cysts in a clutch will wait through eight cycles of wetting and drying before finally deciding to hatch. Fairy shrimp have evolved this ingenious strategy of hedging their reproductive bets in response to the erratic nature of their habitat, and it clearly serves them very well.

Reblogged this on EverWideningCircles.

I’m a little I’m a little surprise that you start the post saying “…which proves to me incontrovertibly that humans are not meant to stick their noses outside the protective layer of Earth’s atmosphere…” I’m biologist, maybe too young and ignorant, but I’m so excited about any step that our species takes outside Earth, the same way I get so excited with any discover on biology, I’m jealous of course of the economic budget that astronomy and space investigations spend, however I think it’s really important to jump outside this planet, I really hope to live enough to see humans steeping in other planet. Actually I haven’t seen “Gravity”, so I really don’t understand what you are talking, even with the spoiler of Sandra Bullock dying. The last space movie I saw was “Europa Report”, were a crew of scientist travel to Jupiter’s moon because they have hope to find life outside Earth.

About your post, magnificent, as always, I really love this blog!!! There are other organisms that fascinated me about their chance to survive out of space; I had a teacher that sent lichens to space in an astrobiolgy experiment, and after two weeks with external space conditions, vacuum, temperature, radiation etc., these were alive. And of course Tardigrades, they also have the same cyst strategy, every time I get one of them under microscope in my samples it’s like a mystic experience about how amazing is life in these planet.

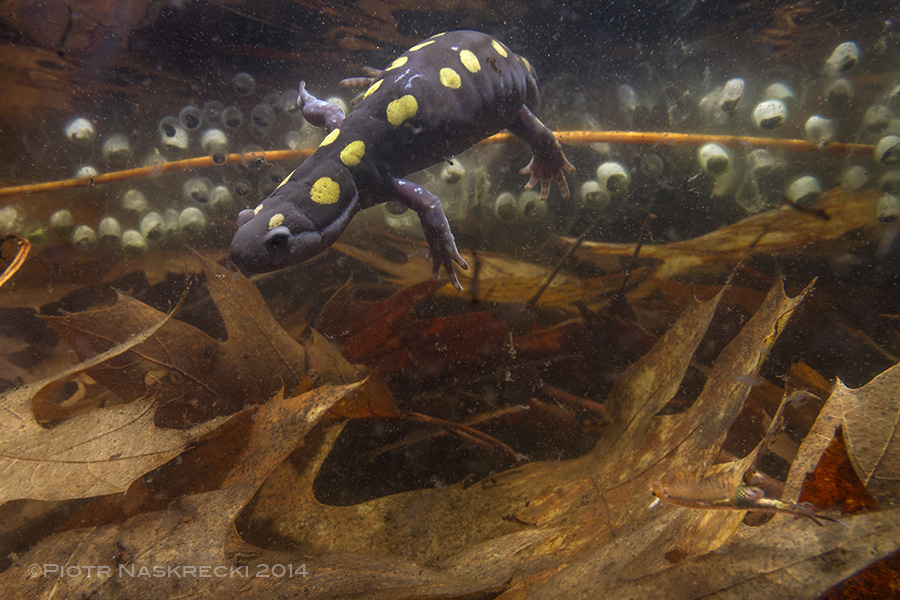

Beautiful. I’d love to find out details of your underwater setup (sounds like you created it yourself?)

I explain most of my photographic techniques, including the underwater setup, in my book “Relics”.

Thanks- I’ll check it out!

We get fairy shrimps on Salisbury Plain in Wilshire, England. A vast area the size of the Isle of Wight where the military practice with their heavy weaponry including tanks, armoured vehicles and artillery. The shrimps are found in the depressions left by the tank tracks and shell depressions.

Fascinating post. I have seen fairy shrimp in vernal pools at over 10,000 feet in the mountains in Montana — definitely a short-season creature, especially at that elevation. (Love the pictures, too — especially the “coral reef” shot!)