Shaun O Connor / BBC Three

Shaun O Connor / BBC ThreeDepersonalisation Disorder: It felt like reality was breaking apart

What would it feel like to smoke cannabis and never sober up? That's how this relatively undiagnosed mental health condition can make sufferers feel

Shaun O'Connor, 37

I was 25 when I thought I had my first experience of Depersonalisation Disorder (DPD).

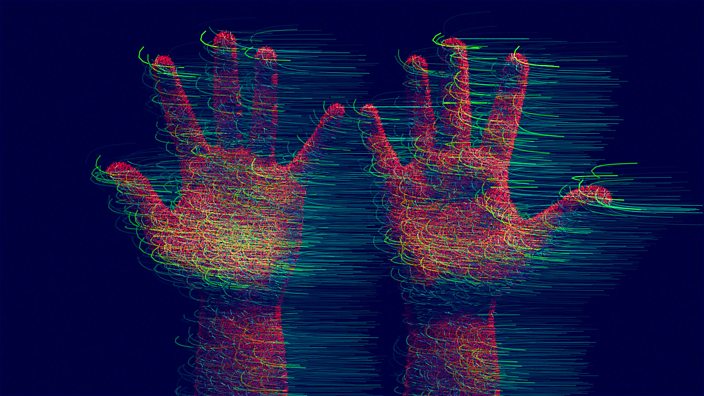

I was home alone at my parents' house, watching TV and it came out of nowhere. All of a sudden, I had an intense panic attack. Suddenly, it felt like the walls were closing in. I stared at my hands but it was like they didn’t belong to me. Even after I’d calmed down, the feeling of fuzziness persisted. It was like I was outside my body, watching reality break apart.

Until that point, I’d never had any serious issues with my mental health. Yes, I’d worried about normal things, like career - I was a gigging musician - and relationships, but I could always bat any negative thoughts away. The only thing I could compare it to was a recent experience I'd had during a trip to Amsterdam when I'd smoked some cannabis, which was far stronger than I anticipated, and struggled to shake off the effects.

That night, I went to bed certain that this strange feeling would pass. But In the morning, it was still there - like I was staring at myself through a pane of glass. I showered. Still no difference. I went down to breakfast, said hello to my parents, and tried to act normal, when I felt anything but. I heard myself talking, but it sounded like someone else’s voice. It was like I had just disconnected from everything and everyone.

The next day, I took the 90-minute bus journey back to Cork, in south-west Ireland, where I was living. I remember being on the bus and feeling terrified. I was sitting in a window seat and felt overwhelmed by the vastness of the landscape rushing past outside. And yet at the same time, none of it felt real. It was like being stuck in a bad dream.

I didn’t know at the time, but what I was experiencing was consistent with the symptoms of DPD.

BBC Three

BBC ThreeAccording to the experts, DPD is a dissociative disorder. It commonly starts with a panic attack and can be a symptom of other conditions. It becomes a disorder when the world around you persistently seems unreal and detached, and when you’re incapable of feeling emotion.

Despite it being thought to affect about 2% of the population - about 1.3 million people - in the UK, according to several studies, DPD is one of the most common but under-diagnosed psychiatric conditions. For young people especially, smoking cannabis can be a trigger.

At first, I was focused on trying to overcome it, but that just seemed to make it worse, and I started having panic attacks. I struggled to eat and lost about a stone in weight in the first month. For me, it was always worse in the morning, so I’d spend half the day in bed with the curtains closed. I went from being someone who loved exercising, socialising and reading to someone who couldn’t focus on anything.

It was horrible. I would look at my dog and the utter strangeness of this animal’s existence would overwhelm me. Or I would look out the window, see the sky and clouds, and get lost thinking about the vastness of the universe. These thoughts would overwhelm me, hundreds of times a day.

BBC Three

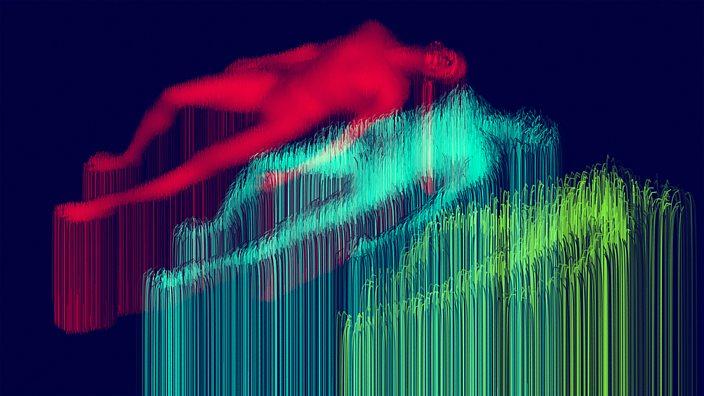

BBC ThreeOn the outside, I looked normal. I was able to go about my life. I showered and watched TV, but this feeling of detachment constantly hung over me. I felt like I’d lost the ability to actively enjoy anything.

After a month, I saw a doctor. I tried to explain that I felt like my memory and perception of time were fragmenting. But describing my symptoms was hard, and I was worried I wasn’t making sense.

My doctor listened and concluded that I was depressed and anxious. He advised me to exercise and prescribed benzodiazepines. But nothing seemed to work, and not knowing what was happening to me just made me more anxious.

By this point, my life was unravelling. I’d cancelled all my gigs, my relationship had ended and I had moved back in with my parents.

My rock bottom came a few months after moving home. There was a family wedding in Scotland and the thought of getting on a plane left me terrified. Somehow, I got through the flight but a weekend of forcing myself to be social was just too much.

At one point, I had to go and lie down in a darkened room. On the plane, on the way back, I had a major panic attack. I honestly believed that reality as I knew it had collapsed in on me.

iStock / BBC Three

iStock / BBC ThreeIt was then, I started researching online and came across an article about DPD - suddenly everything made sense. That led me to forums where I connected with people going through something similar. It was such a relief to realise this was an actual condition and that I wasn’t alone.

At first, I tried things like meditation, massage and lots of exercise to help improve my symptoms - each time it gave me brief relief and then they would return again worse than ever.

Eventually, I booked an appointment with a psychologist who confirmed that my symptoms were consistent with DPD. He told me that the condition normally occurred as a temporary response to trauma or anxiety and that in its chronic form was very rare. But he heard me out and I had a few sessions with him over the course of several months.

It was helpful, but it did highlight to me how hard it is to find a healthcare professional who is familiar with this as a chronic condition even when it seems that there are large communities of sufferers online.

A year in, I realised I had started living my life around the condition. Accepting that actually helped me start to build a new reality. Rather than constantly trying to figure out what was wrong with me, instead I concentrated on the knowledge that often there was no logic to my thoughts. Slowly, things started improving.

I started working and playing live music again. I made myself eat proper meals and put weight back on. And, crucially, I realised that spending time on forums talking about my condition made me feel worse, so I took a break from social media.

From my own research, I discovered that DPD is thought to actually be a defensive mechanism of the brain, designed to protect you in traumatic situations. It’s part of your brain’s fight-or-flight response.

Many people will experience it at some time or another in their lifetime, though it usually only lasts a few seconds or minutes. It only becomes a problem when you focus on it and that creates a vicious circle of anxiety.

Understanding this, that DPD is actually there to protect you, has really helped me with my recovery. If the feelings ever return, at times of extreme stress or anxiety, I now try to recognise them for what they are.

Shaun O Connor

Shaun O ConnorNow over a decade later, I’ve got my life back. I’ve moved back to Cork. I socialise, I travel, and have a successful career as a TV and film director. At my lowest point, I never dreamt that could be possible.

As told to Poorna Bell

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, information about help and support is available here

This article was originally published on 30 May 2019