Proportion, balance and composition

Works by Leonardo Da Vinci, Auguste Rodin, Alberto Giacometti, Edward Hopper and Claes Oldenburg show realistic and unrealistic proportion and scale creating distinctive artwork.

Proportion refers to the dimensions of a composition and relationships between height, width and depth. How proportion is used will affect how realistic or stylisedCreated or shown in a way that draws attention to the way artistic techniques and elements used, rather than appearing natural or realistic. something seems.

Proportion also describes how the sizes of different parts of a piece of art or design relate to each other. The proportions of a composition will affect how pleasing it looks and can be used to draw our attention to particular areas.

The use of proportion is essential for creating accurate images.

Understanding and using correct proportion in life drawingA drawing of a live human model, particularly a nude figure. and portraits allows an artist to create well-balanced, realistic representations of the human form.

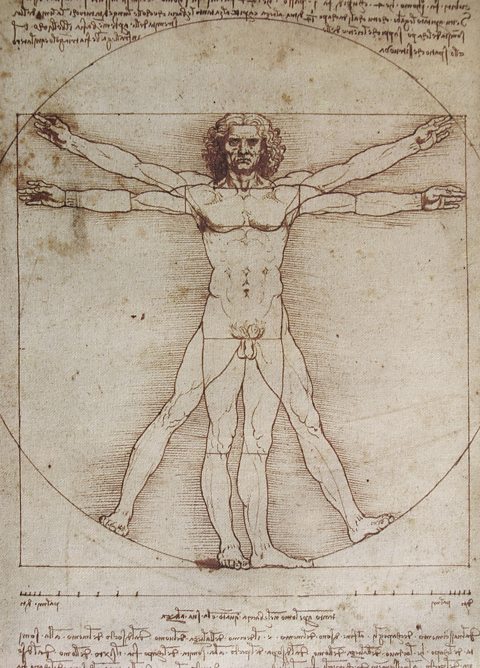

Leonardo da Vinci’s Proportions of the Human Figure (After Vitruvius) (c.1492) was his attempt at depicting the proportions of the human body.

The text around the image describes the scale and proportion of each part of the body.

The length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of a man.

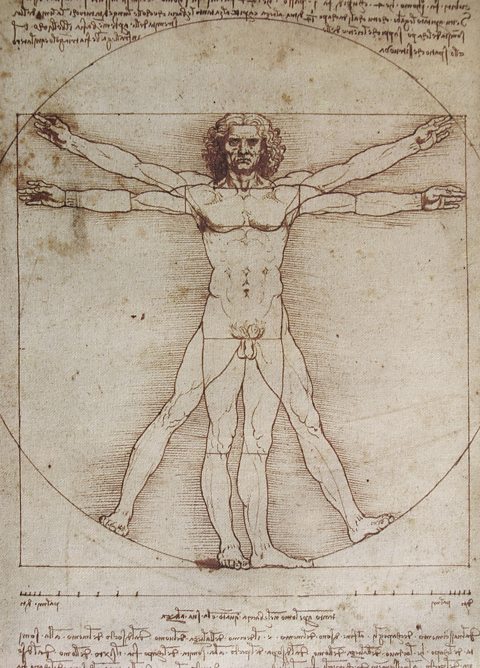

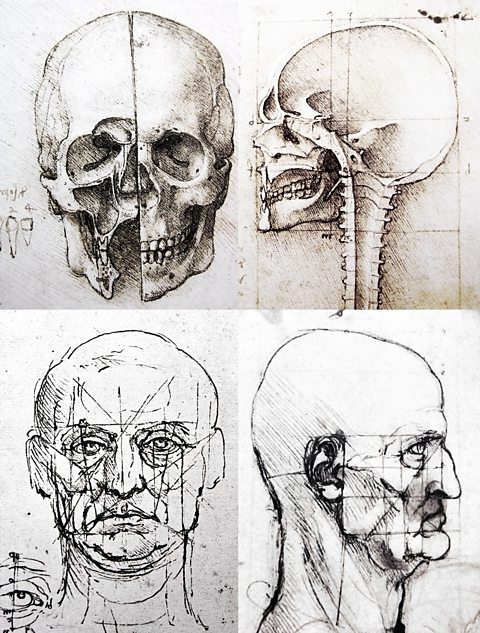

In this set of sketches Da Vinci looked in more detail at the human head. He worked out realistic proportions to use as general rules for the positions and size of different features:

- Eyes positioned halfway down the head

- Top of the ears are in line with the eyebrows

- Bottom of the ears in line with the bottom of the nose

- Pupils in line with the ends of the mouth

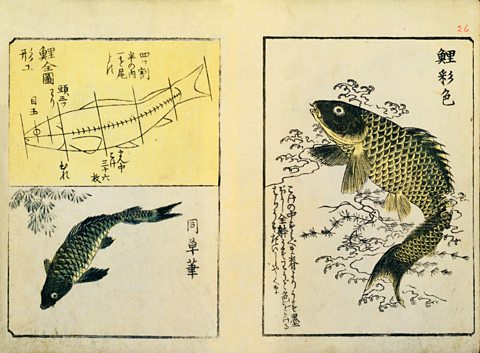

It isn’t just the human form that can be divided into specific proportions. Swimming Carp (Utagawa Hiroshige, 19th Century) shows how the body of a fish has been divided into five equal lengths – one for the head, three for the main body and one for the tail. These proportions are then used in the detailed images.